Last week, we had an unusual public confirmation from a senior figure who disclosed that they had applied for the job of Governor of the Reserve Bank.

I’m pretty sure it has never happened before in New Zealand. The current Reserve Bank Act, which gives the lead role in appointing a new Governor to the Bank’s Board, has been in place since 1990, and this is only the third time there has been a vacancy to fill (as distinct from an incumbent being reappointed). I can’t recall either in 2002 or in 2012 that anyone publicly disclosed their candidacy – although in both cases, it was generally assumed that the incumbent deputies (Rod Carr and Grant Spencer) had applied. It doesn’t happen in other countries, where the Governor of the central bank is generally appointed directly by the Minister of Finance or the President, without an advertised application process. Again, sometimes it is widely known that someone is keenly interested – eg in the US case a few years ago Larry Summers, the former Treasury Secretary – but formal public confirmation is rare or unknown.

But in an (otherwise mostly unremarkable) interview with interest.co.nz’s Alex Tarrant last week, Reserve Bank Head of Operations and Deputy Governor, Geoff Bascand, confirmed his application

He’s put his hat in the ring for the Governor’s job. It’s been rumoured that he’d be the front-runner among the insiders if he wanted to stand, and now he’s confirming that he is going for it.

“The Reserve Bank matters to New Zealand’s economic performance and ultimately therefore to people’s welfare, and I’d like to be part of continuing to make this an excellent and strong institution, and to lead it in a way that it would be really successful for the next five years,” Bascand says.

If he doesn’t get it, then fair play to whoever does. Bascand says he’d like stay on in the Financial Stability role he’s about to take over when Grant Spencer moves into the Acting Governor position for six months starting late-September.

It is an unusual move. In some respects, it is to his credit – after all, one reason people don’t usually answer such questions is that it can be embarrassing to miss out, particularly if you are (or will be by then) the incumbent deputy, and perhaps more so if everyone knows you had applied. But then it is presumably just another part of the multi-year effort by Graeme Wheeler to promote Bascand as his sucessor. After all, the bulk of the interview (authorised by Wheeler) was about monetary policy and making sense of inflation – normally issues that would be handled by either the Governor, or the Assistant Governor/Chief Economist, not by the chief operating officer responsible for things like notes and coins, security and property, communications, the operation of the securities settlement system, HR and the like.

Bascand’s background, of course, is in economics. He started at Treasury, spent quite a bit of time at the old Department of Labour, running for a time its well-regarded Labour Market Policy Group, before moving to Statistics New Zealand where he eventually spent some years as Government Statistician. There seem to be a range of views as to quite how successful that tenure was. A while ago someone sent me a link to a somewhat sycophantic profile written while Geoff was in office. Then again, I’ve heard that SNZ ran into some pretty serious financial problems on his watch.

When Geoff was appointed as Head of Operations and Deputy Governor, I was pretty positive on the appointment. In part, that was the contrast to his predecessor, but much of it was about Geoff’s own merits. Graeme had set out to appoint someone who could contribute to policy, not just keep the operations ticking over, and in Geoff he had found such a person. I hadn’t had a lot to do with him over the years, but what I’d seen left a fairly good impression, of someone who was smart, thoughtful, and level-headed.

It was an interesting move for Bascand himself. He stepped down from a chief executive position in an operational agency to take up a number 3 position at the Reserve Bank My take on day 1 (as recorded in my diary the day his appointment was announced) has remained my view throughout

“No doubt he sees it as a stepping stone back to either Governor or Secretary to the Treasury, via replacing Grant [Spencer] when he goes”

The expectation at the time was that Spencer probably wouldn’t stick around for five years, but as it happens next month Basacand will indeed take up Spencer’s position as Head of Financial Stability and deputy chief executive.

I recall Bascand telling an internal forum a few years ago that he’d only had two more years at SNZ to run, and hadn’t been interested in either joining the international consultancy circuit, or in the sort of operations-focused government chief executive roles that the State Services Commissioner had discussed with him. Even though he’d had relatively limited experience in macro, and none in the financial sector, taking a fairly senior well-remunerated position at the Reserve Bank for a few years was a move back towards “home” – his interests in economic policy. And one that might position him well in time to secure the glittering prizes.

I don’t have many thoughts on how well he has done his day job – head of operations – at the Bank over the past four years. They aren’t areas I pay a great deal of intention to, and are largely inwards-focused anyway. But the new bank notes seemed to be introduced smoothly, and many people seem to like them. So he seems to have been a competent safe pair of hands, presiding over a continuation of the status quo (including, for example, the Bank’s obstructive approach to the Official Information Act, for which Bascand had responsibility).

What has been more noticeable has been the relatively high public profile Bascand has been given by the Governor on economics-related issues, especially in the last couple of years. Bascand’s predecessor as head of operations gave almost no speeches, and certainly none on economic policy and analytical issues (and it is not as if the Bank has moved to do more speeches in total).

And it isn’t as if they have been bad speeches. There are things I’d disagree with in all of them – and I’ve noted his over-enthusiastic embrace last year of the Bank’s new labour market capacity indicator – but that isn’t a criticism. If anything, I’ve found Bascand’s speeches the best of those put out by the four Reserve Bank senior managers, and certainly better, on economic issues, than those of the Chief Economist. Bascand’s speeches come closer to comparing with those of senior managers in other central banks, including the Reserve Bank of Australia.

So in a way it isn’t surprising, or inappropriate, that the outgoing Governor has been smoothing the way, allowing Bascand to raise his public profile on economic policy issues, and – in effect – promoting him as the next Governor.

A few months ago the Bank’s Board advertised the position of Governor. In their “candidate profile” they listed the sort of qualities they were looking for. I wasn’t convinced that was the right list, but here is how I see Bascand against that list of characteristics. My scale is 1 to 5, with 5 the best possible.

| Outstanding intellectual ability |

|

3.5 |

| Leader in the national and international financial community |

|

2 |

| Substantial and proven leadership skills in a high-performing entity |

|

3.5 |

| Proven ability to manage governance relationships |

|

4 |

| Sound understanding of public policy decision-making regimes |

|

5 |

| Ability to make decisions in the context of complex and sensitive environments |

|

3.5 |

| Personal style will be consistent with the national importance and gravitas of the role |

|

4 |

The Board had one more quality they were looking for

The successful candidate will also demonstrate an appreciation of the significance of the Bank’s independence and the behaviours required for ensuring long-term sustainability of that independence.

Personally, I suspect that is, in effect, ultra vires. Decisions on the extent, or otherwise, of independence are matters for Parliament. But I suspect Bascand would be a competent safe pair of hands on that count.

Overall, against this set of qualities, Bascand scores well on the “public sector” types of qualities, as he should. We don’t know much about how he’d do as a single decisionmaker in a body with such high profile and extensive functions as the Bank (nor, in truth, do we know that for any of the possible candidates). He is a capable analyst without, I suspect, claiming to be any sort of soaring intellect. Where he probably scores lowest on this list of qualities is that he can’t make any serious claim to being a leader in the “national and international financial community”. No one, I imagine, thinks of a distinctive Bascand perspective on any of the relevant issues. Relatedly, he has no background with financial markets, banking, or financial system regulation – at least beyond what he will have picked up sitting around the relevant committees, incidental to his day job, in the last four years.

It is pretty clear that there is no ideal candidate to be the next Governor (indeed, I heard at secondhand that the chair of the Board has said as much). If so, Geoff Bascand strikes me as having the inside running if the powers that be are pretty content with things as they are, and aren’t looking for anything materially different over the next five years than they’ve had in the last five. He is, after all, the only serious potential internal applicant, and the Board members have been able to see him every month for the last four years and take his measure. Things probably wouldn’t run badly off the rails with Geoff in charge, and in some respects I expect he’d been a little better than Wheeler.

That is in the nature of a conditional prediction: if you think things have mostly been just fine at the Bank why go past Bascand?

But if he looks more or less suitable (given the slim alternative pickings) on the face of it, I still remain somewhat uneasy about appointing Geoff Bascand as Governor, in which position he alone would have personal legal responsibility not just for monetary policy, but for a wide range of regulatory interventions. Some of that has been because he has been a key member of the Bank’s top-tier over the last four years, when monetary policy hasn’t been done well, and hasn’t been communicated well, and when the regulatory interventions have compounded, backed up by not particularly persuasive analysis. I wonder if he’ll be able to demonstrate to the Board or the Minister that he was trying to influence the Governor towards better approaches? Or even that he has learned something from those unsatisfactory experiences?

But my impression is that he is more a follower and capable implementer than a leader. I was exchanging views a few weeks ago with another former colleague and we both noted that when Geoff first joined the Bank he’d seemed good and open, but quickly seemed to pick up the (internal) political signals and fall into line. At a point when I was a lone internal voice on monetary policy I recall his somewhat strident objection that anyone could take a different view – without ever making the effort to come and talk it over and understand a difference of perspective (in an area riddled with uncertainty).

Then, of course, there were episodes like the Toplis affair. Graeme Wheeler had got a bee in his bonnet about Stephen’s Toplis’s criticisms, and had all his fellow governors meet individually with Toplis to try to get him to back off. Is that the sort of behaviour Bascand regards as acceptable from a top public servant? And, if not, why did he simply go along – after all, his day job didn’t involve contact with commercial bank chief economists? Did he try to persuade the Governor to let it go?

Or the OCR leak episode. I’m reluctant to make too much of it, because I was involved. Then again, one collects data partly through experiences with people. There is nothing in Geoff Bascand’s involvement in that episode, as revealed by the material the Bank had to release, that suggests someone with the sort of stature, and decency under pressure, that would mark him out from Wheeler. Bascand was the senior manager responsible for external communications, lock-ups etc, as well as the one who commissioned the leak inquiry.

One could even think about Geoff’s speeches and interviews. As I’ve already mentioned, I think they’ve been quite good. But there isn’t any hint of a fresh or distinctive angle to them (with the possible slight exception of comments around immigration in the Tarrant interview, which I would welcome). Sure, the Governor is the sole decisionmaker, and it is his line that needs to be conveyed primarily. But in a substantive speech a thoughtful senior adviser should be able to offer fresh insights or angles, without making trouble with the boss. There is little sign Bascand has.

But my most sustained involvement with Geoff Bascand has been as fellow trustees of the Reserve Bank superannuation scheme over the past 4+ years. Geoff serves as alternate for the Governor, and I’m an elected members’ representative. Until late last year, Geoff was chair of the trustees (probably an illegal appointment, but that was an issue for those who appointed him – the Board – not for him personally).

Trustees of superannuation schemes – regardless of who appointed/elected them – are required to act in the best interests of the beneficiaries of the trust, in this case, the members and pensioners. A defined benefit superannuation scheme is a complex beast, involving huge elements of trust reposed in the trustees by members stretching over many decades (from memory, our median pensioner is now aged about 85). The regulatory regime for superannuation schemes in New Zealand is quite limited – something I have mixed feelings about, given my generally support for less regulation – but there have long been statutory provisions, judicial precedents, and the obligations of the specific trust deed and rules themselves. These days, superannuation schemes are the responsibility of the Financial Markets Authority – a fellow regulator that Geoff Bascand will no doubt be dealing with extensively in his new role as Head of Financial Stability for the Reserve Bank (while at the same time a complaint against the trustees sits in FMA’s hands).

The Reserve Bank’s regulatory approach to banks is often characterised as being quite light-handed. Certainly, there are few/no on-site inspections of the sort often seen in other countries. But there are quite onerous requirements imposed on directors and managers, including various strict liability offences – ones, that is, where people are liable whether or not they ever intended to commit an offence. Strict liability provisions are generally repugnant, but there has been no sign of the Reserve Bank walking back its support for such provisions. It is the standard they require of those who hold our money, or make our payments, in New Zealand registered banks. Banks quake at the thought of breaching Reserve Bank regulatory requirements (we see it in the big buffers they run around the LVR limits).

Given this stern approach to the regulation of entities they have statutory responsibility for, you might suppose that they would consistently seek to adopt a “whiter than white” approach to the management of the long-term financial entity they themselves sponsor. It isn’t an entity that is exactly invisible to the Bank either: successive Governors have been trustees, and when they choose not to attend one of their senior managers does so for them. The Bank’s Board – of which the Governor is a member – appoints two of the trustees, and has to approve any rule changes.

Sadly, the standard the Bank – and its senior managers – have taken to the superannuation fund falls far short of the standard they require private financial institutions to adopt. I won’t attempt to bore readers with details. The worst abuses were done some decades ago. Bascand’s involvement has been as these abuses have come to light, and how he has sought to guide the response and reaction.

Three years ago a particularly persistent retired member wrote to the trustees highlighting a series of potential problems around some rule changes in 1988 and 1991. He suggested there was reason to doubt that one significant element of the the 1991 changes had been done lawfully at all, and that key elements of the 1988 changes (which gave the Bank power to, in effect, reduce pensions) had been done without the members’ consent that appeared to have been required by the rules, and under the relevant legislation. Geoff’s immediate response – as chair of a group of trustees, responsible for the fund, and working in the best interests of members – was to write a memoradum to trustees proposing that we agree there was nothing of substance in the submission, and that we do no further investigation.

Fortunately, that did not gain agreement from fellow trustees. I say “fortunately” because with only a little bit of follow-up work it emerged that in fact there had actually been a breach of the Superannuation Schemes Act (members had never actually been told at the time of the 1991 rule change). Fortunately for today’s trustees, the statute of limitations had passed, but the trustees felt obliged to apologise to members for that earlier breach.

With a bit more follow-up work and some legal advice, it became clear that one element of the 1988 changes could simply never lawfully have been made (I think we are all agreed in shaking our heads in wonderment at how this happened), and another change that could lawfully have been made, nonetheless never had the member consent that clearly was required. In fact, the Bank (and the Board) had known of some of these problems for more than 20 years and had never told members (it was no small point – the illegal change had meant that any surplus on wind-up could go the Bank). That in turn has opened up issues around the validity of the consent members gave in the mid 1990s to a rule change that has been worth at least $5m to the Reserve Bank – money it, in effect, extracted from the Fund, having apparently (and wilfully or perhaps otherwise) misled members about the alternatives.

The issue here isn’t the rights and wrongs on specific points. It is about the cast of mind displayed by someone who will shortly be responsible for the regulation of most of our financial intermediation sector, and someone who asks to be given the huge powers Parliament places in the hands of the Governor of the Reserve Bank. Geoff has been quite seriously engaged on the issues where the Bank’s financial interests might be threatened – a process likely to end up in the High Court next year. But he has never shown much sign of acting with the interests of the Fund’s members and pensioners at heart. Despite him, rather than because of him (even though he was chair), some of the issues have continued to be pursued. This isn’t the place to traverse the rights and wrongs of the specific issues; it is about my observation of a senior manager’s inclinations and cast of mind. I’ve noted previously his seeming inability to recognise, and respect, the differences between his responsibilities as a Bank manager, and those as a superannuation scheme trustee – the sort of lack of regard for boundaries that would rightly trouble the Reserve Bank if, say, it was apparent in a director of a New Zealand bank appointed by a foreign parent.

I don’t think Bascand has malevolent intent. He is a pleasant and thoughtful person as an individual. But he doesn’t seem to recognise his responsibilities, and rarely seems to want to dig deeper if he isn’t forced to. Leadership is partly about asking hard questions, and insisting on rocks being turned over even if it might be inconvenient. It is about recognising implications, and looking a bit further ahead than most. Sadly, there doesn’t seem to have been sign of that sort of standard in the Bascand’s approch. A few years ago a prominent person noted that the standard you walk past is the standard you accept. The sorts of standards on display in recent years aren’t those we should be tolerating in a Reserve Bank Governor.

Then again, standards in public life in New Zealand appear to be slipping. As I say, Bascand looks like the probable preferred status quo candidate for Governor. But the status quo shouldn’t be nearly good enough.

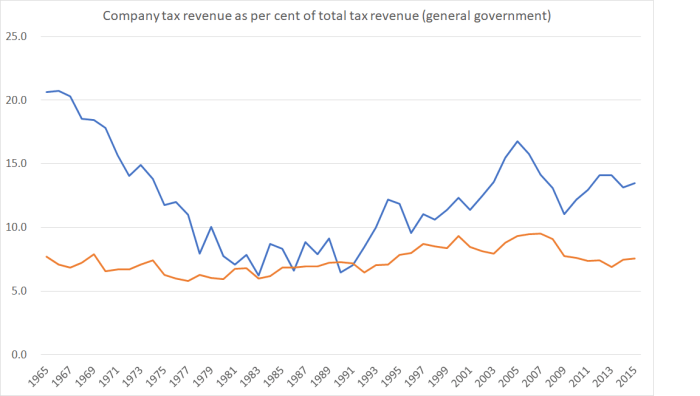

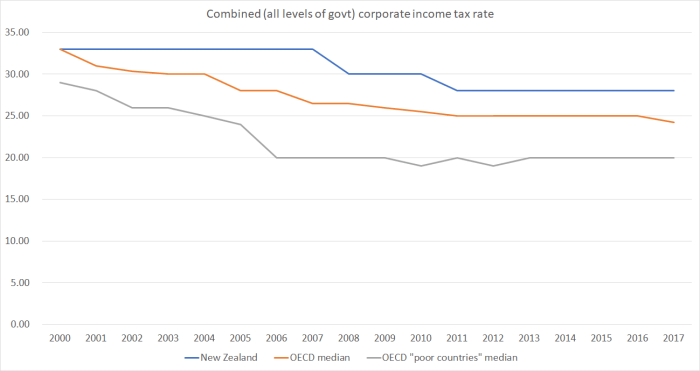

Of the “poor” OECD countries, only Mexico and Portugal now have higher company tax rates than we do. Whereas most of the “poor” countries are closing the income/productivity gaps to the richer OECD countries, Mexico and Portugal (and New Zealand) aren’t. I’m not suggesting it is the only factor by any means, just highlighting the choice that the more successful converging countries have been making.

Of the “poor” OECD countries, only Mexico and Portugal now have higher company tax rates than we do. Whereas most of the “poor” countries are closing the income/productivity gaps to the richer OECD countries, Mexico and Portugal (and New Zealand) aren’t. I’m not suggesting it is the only factor by any means, just highlighting the choice that the more successful converging countries have been making.