My post the other day put the decline in Auckland’s GDP per capita (relative to that of the rest of the country) in some international context using BEA data on the average per capita GDP of various large US cities. As one would have expected, the average per capita in the typical US large city had been rising a little faster than GDP in the US as a whole.

The US data are interesting, but the US is an extremely large country. By contrast, in Europe that are lots of small countries, and (in particular) small countries with a single dominant city. In that respect at least, European experiences might be more interesting to compare Auckland’s experience against.

Eurostat publishes a huge quantity of regional per capita nominal GDP data for the 28 EU member countries. For a few (Malta, Luxembourg, and Cyprus) there wasn’t meaningful data distinguishing the performance of the biggest city from the rest of the country – and in Luxembourg, the data are problematic anyway, since GDP captures economic activity occurring in a country, while many people who work in Luxembourg live in surrounding countries. But that left 25 EU countries, and I went through the data to identify, as accurately as I could, the data for the metropolitan region capturing the largest city in each country. Again, the data are likely to be only indicative – in every metropolitan area, there will be some cases where people work in the area (so their output is in GDP) but live somewhere else (so the person isn’t in the population numbers for that region).

For a few large countries there is no single dominant city. It isn’t an issue in the United Kingdom, France or Poland, where London, Paris and Warsaw respectively dominate, But for Spain, Germany and Italy it is. For illustrative purposes, I used data for Madrid, Hamburg, and Milan respectively.

Eurostat publishes data for 2000 to 2014, but for some cities the data are only available to 2013. For each country, I took the average per capita income of the largest city and calculated that as a ratio of the whole country’s GDP.

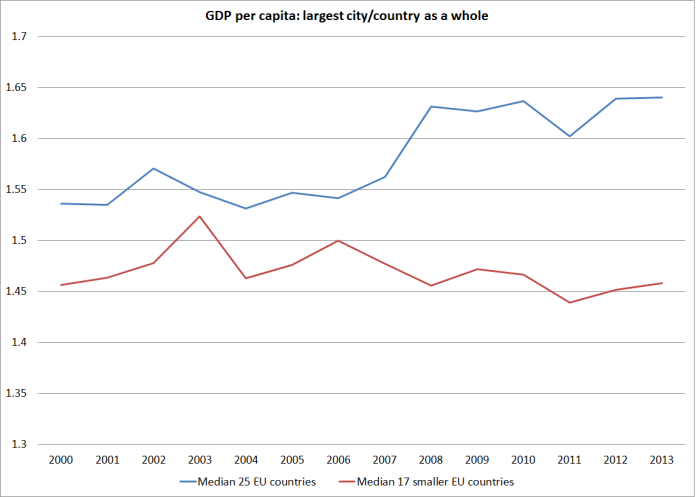

This chart shows the behavior over time in the ratio for the median country. I’ve shown two lines: one for the 17 countries with populations less than around 10 million, and one for all 25 countries.

For all 25 countries, the median had increased over this period. For the smaller countries, there been basically no change over the full period. It is quite different from the picture for Auckland.

I’m not sure why the smaller EU countries did less well on this measure than the full EU sample, but the smaller countries included the countries worst hit by the 2008/09 recession and the subsequent euro crisis. There might be some cyclicality in the relative performance of the largest city does (doing really well in boom times, but suffering more than most in downturns – we see a bit of this in Auckland, which feels the demand effects of fluctuations in migration more than most places).

Auckland’s average GDP per capita is higher than that in New Zealand as a whole (and around 12 per cent than that in the rest of New Zealand excluding Auckland), even if that gap has been closing. But how does that levels gap compare?

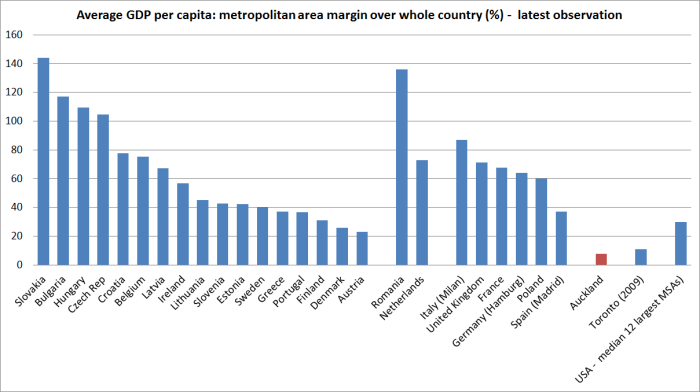

In this chart, I’ve shown the latest observations for how much higher (%) average per capita GDP is in the big city than for the country as a whole for each of the EU country – grouped by small, medium and large. I’ve also shown the median for the twelve largest US MSAs (as per my post the other day), the Auckland numbers, and the experimental numbers for Toronto (from a Statistics Canada research paper) for 2009.

A few things catch the eye. The first is that, at least among the smaller EU countries, it is the ones which have been catching up where the cities are doing best relative to the rest of their respective countries (eg Slovakia, Bulgaria, Hungary, and the Czech Republic). New Zealand was supposed to have been catching up, but hasn’t.

The second thing that catches the eye is just how low the margin between average Auckland incomes and those in the country as a whole is, by comparison with these other countries.

But the third thing that caught my eye, was that the Toronto wasn’t much different. Toronto doesn’t dominate Canada in the way Auckland does New Zealand: Toronto’s population is only about 50 per cent larger than that of Montreal. The Statistics Canada data are only experimental, and they provide estimates for only 2001, 2005 and 2009, but on those estimates both Toronto (in particular) and Montreal had seen a fall in their average per capita GDP relative to that in Canada as a whole.

These days, Canada has higher GDP per capita than New Zealand does (it was the other way round prior to World War Two), but Canada’s productivity growth in recent decades has been about as mediocre as that of New Zealand. Canada has much larger industrial manufacturing sectors than New Zealand does – much of it tied into the US automotive industry – but at heart much of Canada’s prosperity continues to derive from the ability to utilize its vast natural resources. It isn’t an economy whose prosperity seems to be led from its big cities – any more than New Zealand is. That said, Toronto – in such close proximity to the US – seems a much more likely place for successful global companies to base themselves long-term than Auckland.

Canada also operates large scale non-citizen immigration programmes – indeed, the new Canadian government has just announced a material increase in the target rate of immigration (and an reorientation away from economic migration – towards refugee and family). Without knowing more about the Canadian data, I’d be hesitant in drawing too many parallels – and Canada has not faced the same real interest and real exchange rate challenges New Zealand has.

But at least for New Zealand the striking underperformance of our largest city should raise real questions about strategies designed to (or having the effect of) drawing more and more people into Auckland (from abroad – New Zealanders aren’t being attracted), in a country where per capita prosperity seems to rest – and seems likely to continue to rest – on the ability of our people to utilize, ever more smartly, a largely fixed stock of natural resources.

NB: Note that the US figures are measures of real GDP, while for the other countries the data are nominal GDP. For cities other than the US, this will probably have the effect of overstating the margins by which big city per capita GDP exceeds that in the rest of the country, since many prices (including for example housing services prices, but also labour-intensive services) will typically be higher in big cites than in the rest of the country.

According to this chart, Auckland’s population growth is around 3% per year. http://transportblog.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/NZ-Regional-Population-change-2015.jpg. My understanding is that this is nearly all foreign and there is actually a net outflow of people from Auckland to the rest of NZ.

Assuming foreigners have a productivity of half to 2/3 that of native NZers (due to language differences, youth, lack of work experience in high-productivity companies), would this not explain quite a bit of Auckland’s low productivity? Somehow I doubt Ljubljana or Warsaw face the same challenges.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That is a migrant biased comment. My daughters are both New Zealanders and I am a migrant. There is no way their productivity is higher than mine. I had to work for everything I have. They just have to sit back and relax and get handed gifts off the fruit of my labour.

LikeLike

That is certainly one plausible channel for what we see. Having said that, MBIE data suggest that UK migrants (still typically the largest single source country – altho a minority of the total – quickly match the earnings of comparably skilled NZers (suggesting similar productivity).

Personally I suspect is an interaction of a number of factors: non-propitious location in conjunction with only moderately skilled median migrants. There are plenty of not-very-skilled migrants in Houston and New York and San Francisco – who benefit from coming to a place where there are good economic opportunities emerging.

LikeLike

The problem with your use of per capita, you ignore the impact of tourists and international student on the respective cities economy. When you count permanent population and add number of tourists plus students you might get a more realistic picture of GDP rather than trying to point out that migrants have half the productivity of a New Zealander??

LikeLike

The 3.2 million tourists may come into Auckland and stay for a few nights. They really have nothing to spend on in Auckland, The tour groups will organise a trip out to Mt Eden, One tree hill, the museum and a walk along the harbour. All of which are free of charge activities. Then they head out to Queenstown and then the rest of NZ to spend. They just take up a lot of accomodation space but they do not spend very much in Auckland. I do notice the Countdown downtown store does a booming trade in cheap food alternatives for tourists with queues of tourists daily through the checkout counters. I would have thought it is really expensive to have a supermarket right on the waterfront with the views blocked out so that shoppers are not distracted from their shopping experience but the booming trade must offset the rents.

LikeLike

No, I don’t think that is right. International students will be captured in the census as part of the resident population. Tourists won’t, but that is fine – our interest as NZ residents is how much we earn from export industries, including tourism – some of which involve people visiting NZ to buy, and others just involve us shipping stuff to other countries for them to buy.

LikeLike

You cannot have a realistic comparative as Auckland is a stopover point rather than a destination. Certainly John Key is pushing to have more of that tourism dollar spent in Auckland through a Sky City convention centre etc. But most of that tourist dollar is spent outside of Auckland rather than within Auckland. Also Aucklanders travel out of Auckland and the city is pretty dead over the holidays, again tourism dollars spent outside of Auckland during holidays. Trying to lay the blame on migrants is just a clear migrant bias in all your studies that I have seen so far. Misleading studies and biased conclusion which usually ends with migrants are not contributing.

LikeLike

I’m not sure how much we are talking at cross-purposes, but see my response to Blair: I’m not blaming the migrants, who are probably no better or worse than migrants to other cities/countries. I think the real issue is location – NZ isn’t a natural place for generating top notch incomes for many people, and AKld prob less so than much of NZ. If there is an issue, it is about migration policy – which seems blind to the actual characteristics and weaknesses of the NZ economy – not the migrants.

But in a sense your comment makes my point: Akld isn’t a destination, just a place to passthrough. The challenge for cities in any location is what can they earn. Akld has been doing increasingly badly on that score.

LikeLike

@Blair Assuming foreigners have a productivity of half to 2/3 that of native NZers (due to language differences, youth, lack of work experience in high-productivity companies)

Why would you assume any of that? If we are agreed that we have a productivity problem, then we are hardly awash with ‘high-productivity companies’. And can we assume that skilled migrants coming in have only worked in low-productivity organisations? Why does youth make people less productive? Is it reasonable to argue that language differences are as significant as you suggest? As a UK migrant who has encountered little to no barriers to employment in the 13 years I have lived here, I am starting to conclude that it is the attitude of employers and not the skills of migrants that is the problem. Might not the fact that UK migrants do so well is due to the I have lost count of the number of migrants from non-English speaking countries (whose English is perfect, by the way) who are woefully underemployed driving taxis, cleaning, selling tupperware, despite having degrees and plenty of useful work experience. This is anecdotal evidence, I appreciate, but it could easily be tested with data. A survey of migrants from non-English speaking countries could map their level of education to their current employment. I would suspect that an awful lot of wasted productivity would be come clear.

LikeLike

Waiheke is booming as a Tourist destination, both Domestically and internationals….

LikeLike

I’m sure. It is a nice spot, but distinctly limited in its capacity.

LikeLike

I found some population growth figures for the largest cities in the countries you mention, from 2001 to 2011. Some were shrinking, Lisbon, Athens, Vilnius, Riga and Bratislava, maybe Tallinn, Dublin and Budapest, but the others seemed to be growing, Brussels the most, by 3%pa.

So it would seem unlikely there is any correlation between population change and relative GDP per capita.

It may be that sub-categories within overall migration might be an issue ie. is a city gaining/losing its worst/best, but I don’t think that has been demonstrated.

LikeLike

Yes, I agree. What is more, successful cities will typically attract migrants (internal or – where the law allows it – externals).

LikeLike