MBIE (and the Minister of Immigration) believe that immigration is “a critical economic enabler” and, for example, that “immigration has been a driving force in the development of the country’s economy”. Phrases like these, or that immigration is crucial for the success of the government’s Business Growth Agenda, pop up all the time in the papers MBIE released. It is like a mantra they chant, even in face of their own evidence.

The papers repeatedly tell ministers that immigration is a “good thing”, serving not just economic ends but a whole variety of other goals. And yet across all the papers there is hardly a shred of evidence advanced to support the belief – for belief is all it seems to be – that, in the specific circumstances of New Zealand, as the New Zealand immigration system has actually been run over the last 25 years, that there have been any real economic gains for New Zealanders.

And yet, in parallel with the beliefs that appear to drive the system, the papers are full of details and observations which suggest that even officials recognise that actually the immigration system isn’t really working that well. Officials explicitly recognise that large proportions of the people we give permanent residence approvals to (eg lots of family approvals) can’t really be expected to add anything much economically, and many represent a significant net fiscal cost. Officials note that a large proportion of skilled migrant category approvals are to former students in New Zealand, while observing that a large proportion of those have fairly low-level qualifications, and “we seem to have become less effective in retaining the skilled graduates we want”. MBIE notes that “we are seeing a higher proportion of recent migrants (temporary and permanent) employed in industries with overall low or declining productivity. In particular, we are seeing temporary migration increasingly becoming a structural feature of the workforce – with certain sectors (eg dairy) increasingly relying on a ‘permanent pool’ of temporary migrant labour”. I’ve noted previously the MBIE research suggesting that the investor visa approval show little sign of generating much investment in innovative or productivity-enhancing areas. At the other end of the spectrum, MBIE observes “nearly a quarter of recent migrants are working in retail trade and accommodation and food services. They are also likely to occupy a larger proportion of full time positions in these commonly part time industries.”

These issues have become increasingly more serious. The fairly unskilled positions I highlighted yesterday have become a much larger share of residence visa approvals approvals of the last few years (MBIE included a chart in one of the papers, but it won’t reproduce well), and the number of Working Holiday visa approvals has more than doubled in the last decade (to around 55000 per annum now). I had not previously paid much attention to these visas, granted under programmes that seem to have been more about foreign policy objectives (support for a Security Council seat?) than the economic interests of New Zealanders. But MBIE themselves point out that whereas previously most working holiday makers were from wealthier countries, and often didn’t work for much of their time in New Zealand, many more are now from poorer countries (eg Latin American ones), who are working (rather than holidaying) for a much larger proportion of their time.

Here is a paragraph from one of the MBIE papers.

“As noted above, our current immigration settings have resulted in a reducing proportion of labour market-tested work visas. In particular, we have seen a large growth in the number of people on Working Holidays. Many of these people are relatively highly-skilled but take up relatively low skilled jobs in the agriculture, retail trade, and hospitality industries. Given the ease with which these migrants can be employed and the skills they have, it would be unsurprising if employers preferred them to unskilled or otherwise less attractive local workers”.

Officials blithely talk of these visas serving “tourism and foreign policy objectives”, but at whose cost? Isn’t it rather likely that the influx of unskilled workers, or temporary workers doing unskilled jobs, is driving down the relative real wages that these unskilled positions in New Zealand can command? It is a controversial issue in the international immigration literature, but my reading of that literature suggests that in general the effect is real. In the specifics of New Zealand over the last decade, it seems quite likely that it is true here. The effect may well be concentrated in some particular industries. MBIE mention retail trade and hospitality/accommodation, but I suspect it also has real relevance in the aged-care sector. One of the unions has been pursuing a dubious pay-equity case (“dubious” in that I think all such cases are largely meaningless, and probably should be disallowed by statute) in that sector, but it seems much more plausible to me that the huge number of visas given to people working in relatively unskilled positions in that sector will explain part of why wage rates in the sector remain very low. As the government bears a huge proportion of the cost of aged care, this is a direct transfer from relatively unskilled New Zealand workers to the government.

Here are a couple of statistics. Over the last decade (to 2013/14), there has been an average of 44900 residence visa approvals each year (just a touch under the target level of 45000 to 50000 per annum). Of those, only an average of 11600 (or 26 per cent) have been for primary applicants for a visa under the Skilled Migrant or Investor categories. In other words, only a quarter of the permanent migrants we’ve allowed in have been subject to a labour market test at all. That doesn’t sound particularly high, but it gets worse. Recall that, as we saw yesterday, at least 20 per cent of such approvals are for jobs that don’t seem particularly skilled at all, and many of the former students who get residence visas have quite low level qualifications. There is no sign that New Zealand is short of people with certificates/diplomas or even bachelors’ degree (indeed, the empirical evidence is pretty clear that the returns to education here are among the lowest in the advanced world, suggesting a relative glut rather than a shortage that we need to remedy by immigration). Of the primary applicants who were former New Zealand students, over the last decade an average of 318 per annum had honours, masters, or doctoral degrees. Probably no one would quibble too much with allowing these people residence if they wish to stay, but that is a pretty small proportion of the overall permanent migrant inflow.

It isn’t very plausible that such a small group of genuinely highly-skilled migrants – perhaps not many more than 5000 per annum – will have the sort of transformative capacity that officials and governments appear to have been hoping for. And in that sense therefore it isn’t very surprising that we’ve seen no hard evidence of the economic gains to New Zealanders from immigration that keep being touted. Even if the theoretical model of potential gains from immigration were valid for highly-skilled workers, it is hard to expect to see much real empirical gain when 80 per cent or more of the permanent migrants actually simply aren’t that skilled (and in many cases, aren’t even in the workforce), and when there has been a rapidly growing revolving stock of temporary workers mostly doing pretty unskilled jobs.

And, actually, the Minister and MBIE appear to recognise a problem. There is a review of the residence programme taking place at present, which is due to report to Cabinet in November. It is surprising that the media has not paid more attention to this review. On the papers released to me, much of the material is withheld (and it wasn’t what I was after anyway, as when I lodged the request I hadn’t even been aware the review was going on), but the material that was released – in papers only a few months old – is full of talk about reorienting the programme to better maximise the potential economic contribution from the immigration programme. Here are some extracts from a May 2015 paper from Michael Woodhouse to Cabinet’s Economic Growth and Infrastructure Committee.

We already apply a strong focus on the contribution migration can make to economic growth but I believe more can be done. I propose a programme of work to improve:

- The contribution of migration to the labour market

- …..

- The attraction, selection and integration of the investors and entrepreneurs who will help our economy to grow, and to become more innovative and productive

- …..

- The openness of the immigration system to better facilitate the entry of people that contribute to economic growth, whilst more efficiently managing risk.

To maximise the economic contribution of immigration a more strategic approach is needed.

I propose a more strategic approach on when, where, and how to use the immigration system, focusing more deliberately on its contribution to the Government’s wider long-run economic growth agenda.

We have already started using this approach to respond to immediate pressures and opportunities, such as demand for labour in the tourism industry in Queenstown, ICT skills shortages, and the targeting of high-value investor and entrepreneur networks.

Adopting a more strategic approach does not mean that we will place less emphasis on objectives such as family reunification or refugee settlement, but it will mean that policies designed to achieve these objectives will be considered with a more deliberate focus on long-term economic growth.

I intend to also instruct officials to consider the extent to which our immigration settings should target certain industries and regions. For example, we provide some incentives to encourage migrants to settle outside of Auckland…but we can investigate other ways to encourage migrants to settle more evenly across New Zealand.

At one level it sounds good. If immigration is to be a key economic lever or “critical enabler” it would be good to actually maximise the chances of that happening. But the signs are not particularly promising. We’ve already seen the new policy giving many more points to people with job offers outside Auckland. As I’ve noted previously, to the extent that it works at all it must, almost by definition, actually lower the average quality of the “skilled” migrants we allow in. One other aspect of that same package was providing a pathway to residence for people in low-skilled occupations who had been here for several years on work visas. It might be charitable to think about doing so, but it doesn’t have the ring of a ruthlessly skills-focused policy.

But perhaps my bigger concern is the tone that pervades these documents, and Cabinet papers for a minister in a centre-right government, that officials and ministers think they can pick which sectors, firms and regions to favour. The central planning tone is strong, and there is no sign of any evidence that officials and ministers know what they are doing, and can expect to produce the right outcomes. Much of MBIE’s focus appears to be on meeting specific skill shortages – a flavour redolent of the 1960s. Never (I’m pretty sure) in any of the papers do ministers and officials stand back and ask how the market deals with shortages. The usual response is higher prices, not quantitative government interventions.

And never once do the papers recognise that in the short-term the demand effects of increased immigration outweigh the supply effects. That is not just some weird Reddell proposition, it is the standard result that all macro forecasters and analysts (and economic historians) in New Zealand have recognised for decades. Outfits like the Reserve Bank don’t have a dog in the fight about whether immigration is good or bad in the longer-term, but their research has consistently found, and their forecasts have consistently assumed, that when immigration increases, all else equal, inflationary pressures increase. The most recent piece of published research in this area is only a couple of years old.

What that means is that increased immigration does not ease overall labour shortages. In a particular sector immigrants might ease stresses and keep pressures off relative wages for jobs in that sector (aged care workers etc), but in aggregate, immigrants add more to demand than they do to supply in the short-term (a short-term that lasts several years, and each year we have a new large wave or permanent or temporary migrants) and so increased immigration actually exacerbates any net shortages of labour (which is why, all else equal, increased immigration is typically followed by increases in the OCR).

As I said, these issues have been discussed in the New Zealand literature for a long time. Sir Frank Holmes was, in his day, one of the New Zealand’s most eminent economists, straddling the boundaries between academe and public policy (and the private sector) in ways rarely seen today. In 1966 and 1967, when he was Macarthy Professor of Economics at Victoria, he wrote a series of substantial articles for the NZIER on immigration. In some respects they are specific to their time, but they still repay reading. Since coming across them a few years ago, perhaps my favourite quote from them is this

“Give me control of the Government and the Reserve Bank and I can create a labour shortage for you very easily…The resultant boost in demand for goods and services would soon have employers competing vigorously with one another for more workers to help them meet it. If we had started with full employment, we should soon have plenty of vacancies, money wages and prices would rise, and there would be a splendid rise in demand for imports. I think that you might agree that the best cure for that problem might be not more immigration but my replacement by a politician with less generous impulses towards the community. I hope that you will also agree with me that our experience in New Zealand indicates that a big increase in the supply of labour does not necessarily cure labour shortages and certainly does not cure balance of payments problems”.

Persistent shortages across the economy as a whole are usually a sign of too loose a monetary policy (the story in New Zealand in the 00s – and in the much of the 1960s for that matter). Persistent “shortages” in particular sectors are usually a sign that real wages for jobs in that sector should be rising. The central planners at MBIE seem to have a problem with that, or to have barely considered it as a solution.

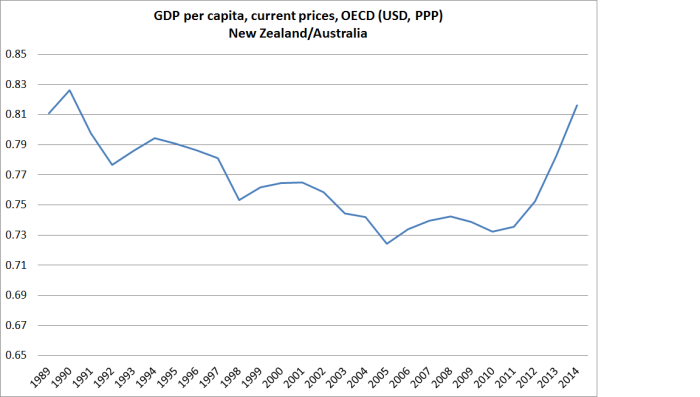

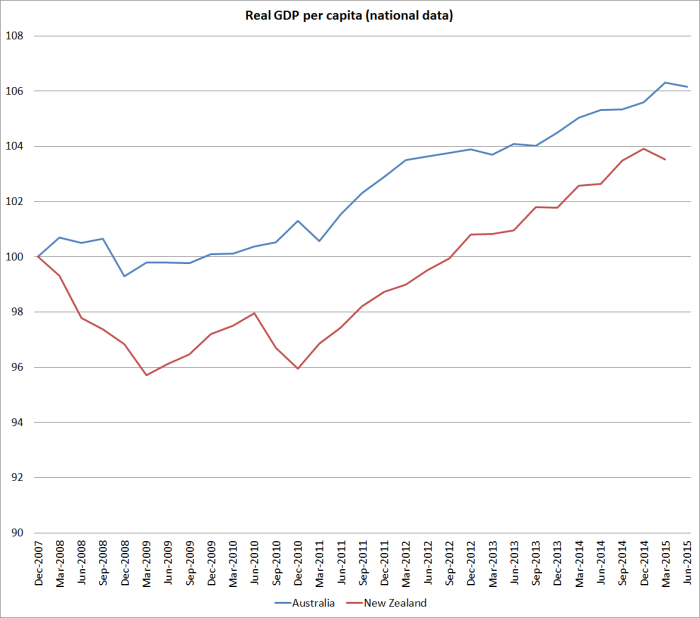

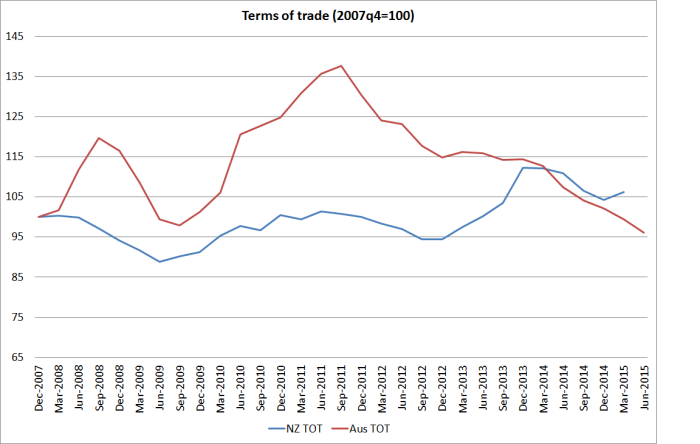

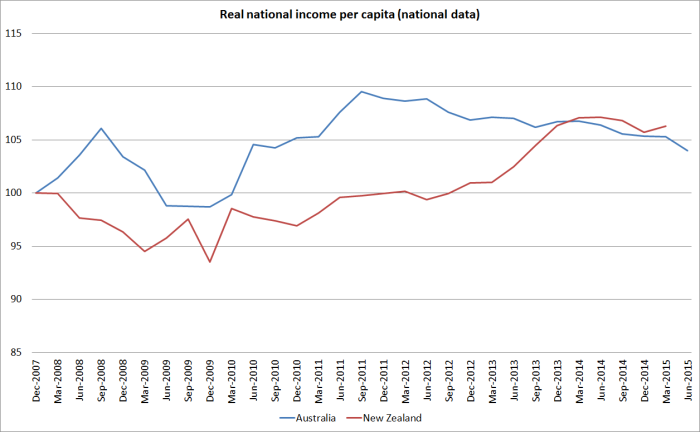

There is an old line about the definition of insanity being doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result. We’ve had one of the advanced world’s largest immigration programmes – almost entirely under government control, since we have total control of our borders – for 25 years, and have little or nothing positive to show for it. We’ve had among the worst productivity growth of any advanced economy in that period, and persistent excess demand pressures reflected in the highest real interest rates in the advanced world, and a persistently overvalued real exchange rate. What gives people any confidence that things are likely to be any better in future?

If the Cabinet is serious about a strategic review, and about maximising New Zealanders’ long-term prosperity by capturing any long-term economic benefits from immigration, I think they need to put a lot more material into the mix, including asking hard questions about why we haven’t seen obvious gains from the large and longrunning programme to date. I’d suggest going back to the drawing board. A helpful input in that context would be a Productivity Commission review, as they are (again) doing in Australia at present.