I did a post a couple of weeks ago suggesting that some of the talk about the long-term real economic costs of financial crises had been exaggerated. My example was US growth over 150 years or so, in which the trends seemed largely undisturbed by the numerous financial crises. It makes a lot of sense that, disruptive as severe recessions can be in the short-term, the long-term economic prosperity of nations is not much affected by financial crises. Growing prosperity is primarily about innovation, in all its dimensions (new technologies, new ways of using them etc), and it isn’t overly plausible that a financial crisis could make that much difference in the medium-term.

The previous Reserve Bank of New Zealand Governor Alan Bollard made this point in a speech he gave in 2012, just before the end of his term (He graciously listed me as co-author, but it was his speech).

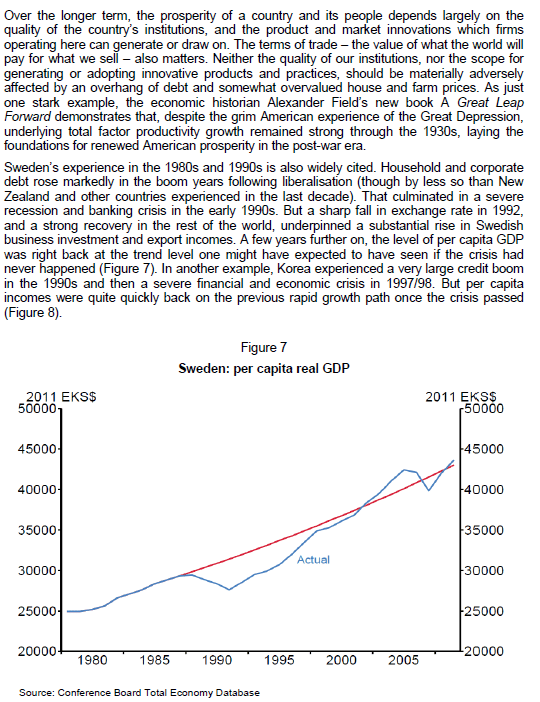

Prior to 2008, the classic post-war systemic financial crises in advanced countries were in Spain, Japan, and the three Nordics (Norway, Finland, and Sweden). Reinhart and Rogoff label them the “big 5”. Since it was close to home, I’ve also had a look at New Zealand’s experience with the crisis of the late 1980s (for offshore readers, this saw – inter alia – a collapse in the share market, numerous major corporate collapses, the failure of a major investment bank, and the near-collapse (twice recapitalised) of the government-owned largest commercial bank) and at the Korean crisis of 1997/98.

Ideally, one might look at TFP data, but it is not available, consistently compiled, for most of these countries in these periods around crises. So I had a look at labour productivity – real GDP per hour worked, drawing from the Conference Board’s database. I was curious how growth in the years after a crisis compared with that in the years leading up to the crisis. In this case, I looked at data for seven years each side of the crisis date.

Crisis dating is itself an imprecise business. For the big 5, I’ve used Reinhart and Rogoff’s dating, and for Korea I’ve used 1997. Dating the New Zealand crisis isn’t easy. I’ve used 1989, which was the year in which several major failures occurred. I could have used 1987, which is when the share market collapsed, never really recovering. I’m not suggesting anything very definitive can be drawn from the comparisons, and there is always a great deal else going on in any economy (at times, structural reforms might be an endogenous response to the crisis, or – as in New Zealand – structural reforms had been going on in parallel.

Here are the results for the big 5 financial crises. In three of the five countries, productivity growth was faster in the years following the crises than in the years prior to the crisis.

And here is what the picture looks like if we add in New Zealand (with 2 possible datings – 1989 is my preference) and Korea. These examples balance up the illustrative sample, but they hardly provide a clear-cut illustration of the idea that financial crises cause permanent costs.

What of the most recent period? If we date financial crises to 2008 (which seems reasonable), there is only six years of annual data since the crisis, and those data are still likely to be subject to considerable revision. But for what it is worth, if we multiply productivity growth since 2008 by 7/6, here is what a chart of pre and post 2008 productivity growth looks like for the US, Ireland, the UK, and for New Zealand, Australia, Canada. No one would dispute the US and Ireland had systemic financial crises rooted in problems in their own countries. My reading of the UK is somewhere in the middle – several of its major banks failed and were bailed out, but in considerable part based on offshore exposures. New Zealand, Australia, and Canada did not experience systemic financial crises.

Across advanced countries as a group, labour productivity growth in recent years has been slower than it was in previous years. But as I’ve discussed previously, this isn’t restricted to (or focused among) countries that have had financial crises. Indeed, the Irish crisis was probably the most severe of any of those in OECD countries, and yet Ireland has reported faster labour productivity growth since 2008 than in the seven years prior to it.

Misallocation of resources that leads to eventual recessions and financial crises come at a cost. With the exception of Japan, each of the crisis countries (pre 2008 and 2008) had nasty recessions associated with their crisis. But to what extent the severity of the recessions was caused by the crises, as distinct from the severe initial misallocation of credit and possibly of real resources, is an open question. And in Japan, and in the post 2008 experience, the role of demand shortfalls (resulting from combination of the near-zero lower bound, and fiscal constraints) is also likely to be very relevant in many countries.

We should be hesitant about concluding the financial crises have material long-term economic costs. If they don’t, the case – embraced by regulators, whose incentives might be somewhat skewed – for more extensive and intrusive financial regulation is materially weakened. Indeed, if the crises might have been caused in large part by policy choices, we want to be even more wary of handing additional powers to regulatory agencies of the same state whose actions/choices caused the problems in the first place. The role of active or passive policy choices in creating conditions that drove down lending standards in the recent Irish and US cases is pretty clear, but policy also played a key part in many of the 1980s crises (fixed exchange rates in the Nordic countries, and the difficult transition from hitherto excessively regulated banks and financial markets in the Nordics and in New Zealand).