I’d been planning to write a post today about the near-complete cone of silence that seems to have descended over elite New Zealand around the Jian Yang scandal. That a former member of the Chinese intelligence service, former (perhaps present, if passive) member of the Chinese Communist Party, still in the very good graces of the Chinese authorities – never, for example, having denounced the oppressive expansionist regime he served – sits in New Zealand’s Parliament, nominated to again win a seat in Parliament on Saturday, is both astonishing – at least to those like me who haven’t been close observers of such things – and reprehensible. That it seems not to bother anyone in, or close to, power (at least enough to do or say anything) is perhaps even more alarming. There was a wave of stories in the first 24 hours after the Financial Times/Newsroom stories broke, and then……well, almost nothing.

There has been a lame excuse offered up: Jane Bowron in the Dominion-Post noted that it was election time and there is lots else to write about. And actually I more or less buy the line that there aren’t the journalistic resources to do much new digging right now. But (a) it is election week, when we make choices about the sort of people and parties we want governing us, and (b) how hard can it be to ask, and keep on asking, political leaders of whatever stripe about this story, on the basis of what has already been published, and on what Yang has already acknowledged (years later)? Report, again and again if necessary, that a key political figure refused to comment, but don’t simply ignore the story.

But then Newsroom this morning had another important story, putting the Yang story in the much wider context of the systematic efforts of the Chinese authorities (state and party), and drawing on a new paper by University of Canterbury politics professor, and expert on China and its ambitions, Anne-Marie Brady. Her paper Magic Weapons: China’s political influence activities under Xi Jinping was presented at a conference in the United States a few days ago: the conference title “The corrosion of democracy under China’s global influence”. What makes it so compelling is that it is a detailed case study of China’s efforts in New Zealand. It isn’t heavy analysis, but simply nugget after nugget that builds a deeply disquieting picture, and perhaps makes disturbing sense of the cone of silence around Jian Yang. Every thinking New Zealand should read Brady’s paper.

As she notes early in the paper

New Zealand’s relationship with China is of interest, because the Chinese government regards New Zealand as an exemplar of how it would like its relations to be with other states. In 2013, China’s New Zealand ambassador described the two countries’ relationship as “a model to other Western countries”.

With, one hopes, a degree of hyperbole, she goes on to note (quoting an anonymous source)

And after Premier Li Keqiang visited New Zealand in 2017, a Chinese diplomat favourably compared New Zealand-China relations to the level of closeness China had with Albania in the early 1960s.

She goes on to outline the huge effort China puts in to attempting to manage the Chinese diaspora, whether in New Zealand or other countries.

After more than 30 years of this work, there are few overseas Chinese associations able to completely evade “guidance”—other than those affiliated with the religious group Falungong, Taiwan independence, pro-independence Tibetans and Uighurs, independent Chinese religious groups outside party-state controlled religions, and the democracy movement—and even these are subject to being infiltrated by informers and a target for united front work.

She records that these efforts have greatly intensified under Xi Jinping – as internal repression in China has as well.

Even more than his predecessors, Xi Jinping has led a massive expansion of efforts to shape foreign public opinion in order to influence the decision-making of foreign governments and societies

This includes seeking, largely successfully, to gain effective control over Chinese-language media (with exceptions as above) and encouraging political involvement of overseas Chinese.

This policy encourages overseas Chinese who are acceptable to the PRC government to become involved in politics in their host countries as candidates who, if elected, will be able to act to promote China’s interests abroad; and encourages China’s allies to build relations with non-Chinese pro-CCP government foreign political figures, to offer donations to foreign political parties, and to mobilize public opinion via Chinese language social media; so as to promote the PRC’s economic and political agenda abroad.42 Of course it is completely normal and to be encouraged that the ethnic Chinese communities in each country seek political representation; however this initiative is separate from that spontaneous and natural development.

And neutralising, or even coopting, members of local media and academe.

Coopt foreign academics, entrepreneurs, and politicians to promote China’s perspective in the media and academia. Build up positive relations with susceptible individuals via shows of generous political hospitality in China. The explosion in numbers of all-expenses-paid quasi-scholarly and quasi-official conferences in China (and some which are held overseas) is a notable feature of the Xi era, on an unprecedented scale.

As she notes, New Zealand hasn’t been immune to that strand of influence. In part we do it to ourselves – there are, for example, the New Zealand government sponsored New Zealand China Council media awards. Or sponsored trips for selected journalists to China, paid for the New Zealand China Friendship Society (didn’t the Soviets used to sponsor such bodies?). It becomes harder to ask awkward questions when awards and sponsored travel opportunities might depend on not doing so. I don’t suppose the New Zealand China Council – chaired by Don McKinnon, including the chief executive of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade – would be at all pleased by open scrutiny and debate about Jian Yang’s background, his ongoing relationship with the Chinese authorities, and his presence in our Parliament. It might – no doubt would – upset China, not a country known for its tolerance of robust scrutiny and challenge. These days, one has to wonder whether we still are, at least when it comes to China.

One of the most interesting bits of the paper is Brady’s discussion of why New Zealand interests China. Here is some of her text

But New Zealand is of interest to China for a number of significant reasons. First of all, the New Zealand government is responsible for the defence and foreign affairs of three other territories in the South Pacific: the Cook Islands, Niue, and Tokelau—which potentially means four votes for China at international organisations. New Zealand is a claimant state in Antarctica and one of the closest access points there; China has a long-term strategic agenda in Antarctica that will require the cooperation of established Antarctic states such as New Zealand. New Zealand has cheap arable land and a sparse population and China is seeking to access foreign arable land to improve its food safety. ……

New Zealand is also a member of the UKUSA intelligence agreement, the Five Power Defense Arrangement, and the unofficial ABCA grouping of militaries, as well as a NATO partner state. Breaking New Zealand out of these military groupings and away from its traditional partners, or at the very least, getting New Zealand to agree to stop spying on China for the Five Eyes, would be a major coup for China’s strategic goal of becoming a global great power. New Zealand’s ever closer economic, political, and military relationship with China, is seen by Beijing as an exemplar to Australia, the small island nations in the South Pacific, as well as more broadly, other Western states.

Not all of it is wholly compelling – Tokelau isn’t independent, and the Cooks and Niue aren’t members of many international organisations. But the overall story makes a lot of sense. If you wonder about the Antarctic bit, Brady is an expert on China’s Antarctic policies and aspirations.

On the other hand, you have to wonder quite why New Zealand governments should pay so much court to China. Exports from New Zealand firms to China account directly for only about 5 per cent of our GDP (exports from Canadian firms to the US are, by contrast, 23 per cent of Canada’s GDP). And many of those exports – notably dairy products and lamb – are for relatively homogeneous products that would end up sold elsewhere, perhaps at lower prices, if somehow China restricted the ability of New Zealand firms to export. There is, of course, the Chinese student market – almost half the total student visas issued last year were to Chinese students – but, as is now well-recognised the export education industry is a pretty troubled and distorted one, often as much about immigration aspirations as about the quality of the education product on offer. So university vice-chancellors, and their colleagues in lesser institutions, might have a strong private interest in not upsetting China but it isn’t obvious that the citizenry of New Zealand share that interest, when it comes to defending our values and our system.

Brady argues that the emphasis on the China relationship appears to have greatly intensified under the current government

the current prominence afforded the China relationship has accelerated dramatically under the government that won the election in 2008, the New Zealand National Party. The National Party government (2008-), follows two main principles on China: 1. The “no surprises” policy,72 which appears to mean avoiding the New Zealand government or its officials or anyone affiliated with government activities saying or doing anything that might offend the PRC government; and 2. a long-standing emphasis on “getting the political relationship right”, which under this National government has come to mean developing extensive and intimate political links with CCP local and national leaders and their representatives and affiliated actors in New Zealand.

She provides a concrete example of this desperate desire not to offend.

This cautiousness to not rock the boat over New Zealand-China relations lay behind New Zealand’s reluctance to join the USA and Australia to criticize China’s military base building activities in the South China Sea. Following massive pressure from Australia and the US, New Zealand Prime Minister John Key (2008-2016) and other ministers made a series of muted remarks in 2015 and 2016, but it was far from what New Zealand’s allies had hoped for, who have frequently accused the National government of being soft on China. The New Zealand National government’s reticence to speak out on this issue, despite the fact New Zealand has the fourth largest maritime territory in the world and relies on respect for international norms for the protection of its rights, is one telling example of the effectiveness of China’s soft power efforts in New Zealand in recent years.

Brady highlights concerns around a number of local Chinese politicians – not just Yang, but also Labour’s Raymond Huo and former ACT MP (and until recently, deputy leader) Kenneth Wang. You can read some of those concerns, and apparently serious questions, for yourself.

Through much of the rest of her article, Brady writes in some detail about the various webs of connection that help create an economic interest among many leading New Zealand figures in not rocking the boat. As I’ve noted previously, the Chinese banks operating in New Zealand have four former senior National Party figures on their various boards (Jenny Shipley, Ruth Richardson, Don Brash and former minister Chirs Tremain). Jenny Shipley served for a number of years on the main parent board of one of the Chinese banks (all effectively still controlled by the Party) and has a number of senior appointments on boards sponsored by the Chinese government. Senior National figures are closely tied into companies exporting dairy products to China.

As Brady notes, for the time being the issue is mostly around National Party figures, but surely only because their party is currently in government. It seems unlikely that the Chinese would not be similarly keen on aligning Labour figures should the government change here. She repeats the story of the fundraising for Phil Goff’s mayoral campaign: at a charity auction in Auckland, a bidder from China paid $150000 for the Selected Works of Xi Jinping.

Brady concludes with a big picture

SELRES_424b093c-5aa4-4648-8116-11850f67a020New Zealand’s needs to face up to some of the political differences and challenges in the New Zealand-China relationship and to investigate the extent and impact of Chinese political influence activities on our democracy. This study is a preliminary one, highlighting representative concerns. New Zealand would be wise to follow Australia’s example and take seriously the issue of China’s big push to increase its political influence activities, whether it be through a Special Commission or a closeddoor investigation. It may be time to seek a re-adjustment in the relationship, one which ensures New Zealand’s interests are foremost. Like Australia, we may also need to pass new legislation which better reflects the heightened scale of foreign influence attempts in our times. New Zealand can find a way to better manage its economic and political relationship with China, and thereby, truly be an exemplar to other Western states in their relations with China.SELRES_424b093c-5aa4-4648-8116-11850f67a020

That rings true to me. But for now, my interest is in the specifics of the Yang case. It is extraordinary that a man with such a past – and no interest in denouncing the tyrants he worked for – is in our Parliament, and seems likely to be in it again next week. But more alarming is the total silence of our elites.

I can’t believe that most of them – media, politicians, past politicians – are really comfortable with the situation. But if they put their personal economic interests ahead of the interests, and values, of the people of our nation, by just keeping quiet, it makes no difference that they might be a little uncomfortable. They have, in effect, sold their own country, and its values, for a mess of potage.

The media, and the academic community (the ones who still want to get to China anyway) are just as culpable – most of the media not even now doing their most basic job and asking the questions – but I jotted down a list of senior politicians – past and present – that we should be able to look to for leadership.

We could look to current and past National Party leaders. But Key and English have led the charge to strengthen the “vassal” relationship with the Chinese (and Brady reports that Key is now working for Comcast on its projects in China), and were the National Party leaders when Yang was recruited. What about their predecessors? Well, Brash chairs a Chinese bank , and Shipley has multiple Chinese directorships etc. It would be costly to speak out. But what about Jim Bolger – certainly willing to speak out recently about “neoliberalism”, but what about submission to China’s interests?

What about former National ministers of finance. Well, there is English, and Ruth Richardson (various Chinese directorships) – and Bill Birch, but he is now quite elderly. Or former Foreign Ministers? Well, McCully should probably be asked about Saudi sheep deals…..and led the strategy to cosy up to China. And Don McKinnon, but then he chairs the government’s China Council. Any of these people could speak up – sometimes principles cost – but, sad as it is, perhaps it is no surprise they don’t.

And normally, a week out from an election you might expect strident comment from the Opposition. But this time? Nothing? And if it would disrupt the “relentlessly positive” narrative, what about former eminent Labour figures – Cullen, Moore, Palmer, Goff, Clark? Not a word though.

What of ACT’s leader? Is this the sort of standard he accepts in the party he depends on? What of the leaders of the Greens or the Maori Party? Not a word from any of them.

The pattern of silence should leave us wondering just whose interests our leaders have been serving. There is something to be said for politicians leaving office late in life and settling quietly into a dignified retirement. It would be quite deeply disturbing if any of them are shaping their in-office approach to (eg) China with a view to their after-office economic opportunities – consciously or otherwise. A submssive approach to the Chinese government and party isn’t in our interests – even if it might be in the personal interests of some present and former politicians and some business owners.

There are other people the media could – if they were so minded – seek comment from. Mai Chen, for example, chairs something called New Zealand Asian Leaders. Surely Jian Yang- with such a disturbing past, so much hidden from the public, and a quite disturbing alignement with Xi Jinping’s Beijing now – can’t be the sort of Antipodean Asian leadership they envisaged?

We aren’t, of course, a 1960s Albania to China. But what the Yang episode highlights, as one example of the more general pattern Brady draws our attention to, is that we seem to have gone some considerable way down a slippery slope and need to pull back. Some hard questions from the media, and some honest answers from politicians, would be a start. And perhaps some courage on behalf of at least one of those decent people who has got too close to Chinese interests – initially with the best will in the world – to say “enough”?

Before we (well, the rest of us) vote perhaps?

UPDATE (Wednesday pm). This Herald article is at least in start in terms of the mainstream media addressing the issues and approaching some of the people concerned.

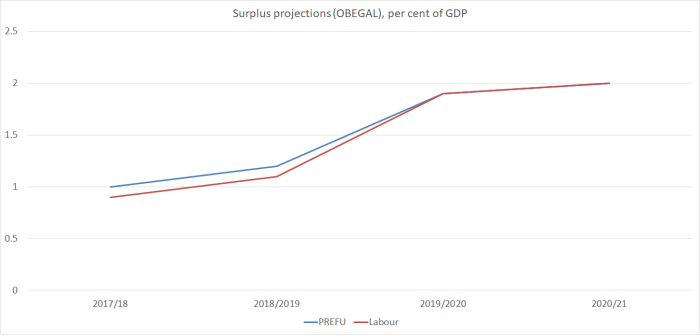

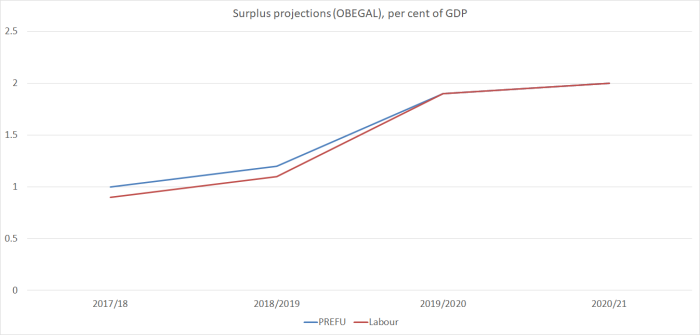

When net core Crown debt is already as low as 9.2 per cent of GDP – not on the measure Treasury, the government and Labour all prefer, but the simple straightforward metric – what is the economic case for material operating surpluses at all? With the output gap around zero and unemployment above the NAIRU, it is not as if the economy is overheating (the other usual case for running surpluses). Even just a balanced budget would slowly further lower the debt to GDP ratios. One could mount quite a reasonable argument for somewhat lower taxes (if you were a party of the right) or somewhat higher targeted spending (if you were a party of the left, campaigning on structural underfunding of various key government spending areas).

When net core Crown debt is already as low as 9.2 per cent of GDP – not on the measure Treasury, the government and Labour all prefer, but the simple straightforward metric – what is the economic case for material operating surpluses at all? With the output gap around zero and unemployment above the NAIRU, it is not as if the economy is overheating (the other usual case for running surpluses). Even just a balanced budget would slowly further lower the debt to GDP ratios. One could mount quite a reasonable argument for somewhat lower taxes (if you were a party of the right) or somewhat higher targeted spending (if you were a party of the left, campaigning on structural underfunding of various key government spending areas).