The Productivity Hub is a partnership of agencies which aims to improve how policy can contribute to the productivity performance of the New Zealand economy and the wellbeing of New Zealanders. The Hub Board is made up of representatives from the Productivity Commission, the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment, Statistics New Zealand and the Treasury

The Productivity Hub yesterday hosted a symposium in Wellington with the title “Growing more innovative and productive Kiwi firms”. “Growing” things is usually something gardeners do – people doing stuff to things. So the title perhaps carried somewhat unfortunate connotations of successful firms being the products of government action. That probably wasn’t their intention, at least not wholly, but then again it wasn’t entirely out of line with the list of attendees – 161 names, of whom at least 150 would have been bureaucrats, academics, and the like. There appeared to be only a very small handful of people from the (non-consultancy) private sector.

I had to leave early (schools finish at 3pm) and I gather I might have missed the two best papers of the day, from a couple of overseas academics. But what I did see was pretty disappointing. It confirmed a sense that our leading government agencies still have no real sense of what explains New Zealand’s persistently disappointing productivity performance, or of what – if anything – might be done to remedy that. But there is a hankering to “do stuff” in the innovation/research area.

The day didn’t start particularly convincingly when, in his introductory remarks, a senior member of the Productivity Hub remarked that they had been along to see the Minister of Statistics to tell him about the value of the research that was being undertaken under the auspices of the Hub. The Minister had, apparently, asked what was in it for the plumber from Masterton. The bureaucrats replied that research showed that good human resource management was good for productivity, so the plumber might get value from knowing that treating his staff well, and asking about their weekends on Monday morning, might be good for business. I could only imagine the reaction of the plumber to learning that his taxes had paid for this stunning insight.

Of course, there is more to the research than that. But official agencies still don’t seem to be getting to the bottom of the issues, and are mostly identifying symptoms (perhaps understanding them in a better and richer way) rather than causes.

In some circles – perhaps especially in MBIE – there is considerable enthusiasm for additional activity encouraging businesses to do more research and development. But again it mostly seems to be tackling symptoms rather than getting to a deeper understanding of why New Zealand firms rationally make the choices they do.

Consistent with that, we heard from Sarah Holden at the quango Callaghan Innovation. Their government-mandated aim is to increase business enterprise spending on research and development (“BERD”) from around 0.6 per cent of GDP to 1 per cent of GDP. To do so, apparently they have already spent $403 million in R&D grants in their first two years. It is early days, so I might have expected just upbeat rhetoric. But to her credit, Holden told us that the experience to date was that “big companies do fine without us – but like the grants – while small companies don’t use Callaghan’s R&D facilities as much as Callaghan would like. The grants don’t seem to be making much difference.” It was tempting to ask “so why are we spending all this money so freely?” No one did so, at least openly.

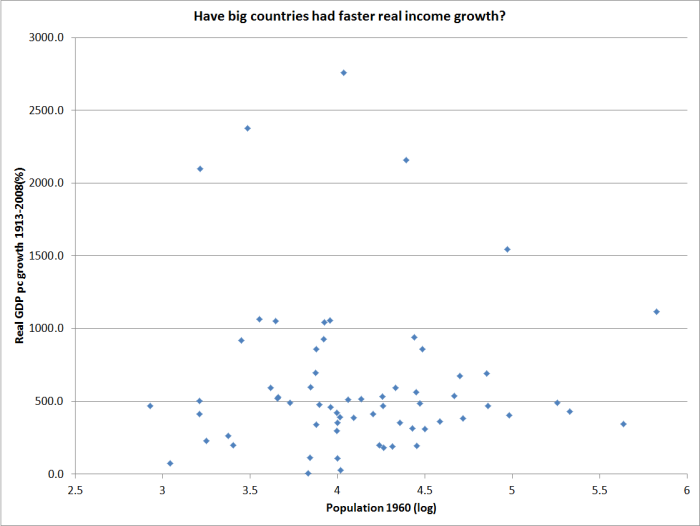

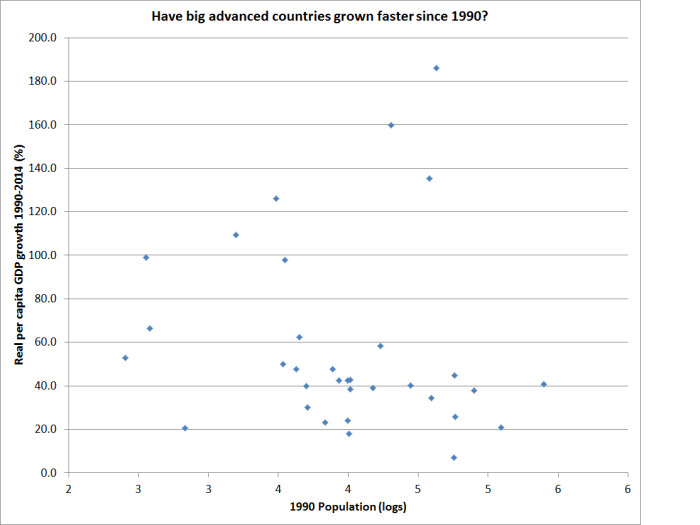

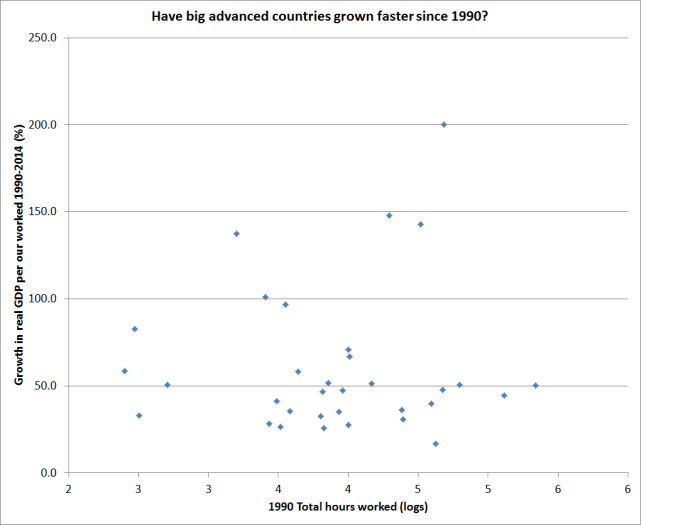

We also heard an interesting presentation from Shaun Hendy, from the University of Auckland. He had some fascinating data on the importance of networks etc, and the way in which the number of patents per capita increases as the size of the city increases. But it wasn’t clear that he was aware that there is no real evidence that big countries, or countries with big cities, have been achieving faster productivity growth than small countries.

Perhaps the weakest part of the day was the keynote address from Gabs Makhlouf, the Secretary to the Treasury, headed “Innovation, diffusion, and markets”. At such conferences, agency heads usually content themselves with some brief introductory or concluding remarks. But this was billed as a keynote address. Gabs apparently thought he had something enlightening to say on the issues of innovation, productivity, and economic performance. He didn’t. There was a lot of “all hands to the pump” rhetoric – which seemed like a convenient substitute for hard analysis. What evidence, for example, does the Secretary have that the private sector is responding inappropriately, given the policy framework set by successive governments?

He was, however, adamant that the answer to the disappointing productivity performance is not a lower exchange rate. I was quite taken aback by that – especially when he went on to assert that to believe that a lower exchange rate was important was to put oneself on “the road to doom”. When I checked the Treasury’s most recent Briefing to the Incoming Minister, they didn’t seem to share that perspective – although they rightly pointed out that a different monetary policy regime is not a path to a sustained lower real exchange rate. As ever, it would be interesting to know what lies behind some of the Secretary’s assertions.

He also noted that New Zealand was not able to get the agglomeration advantages of some of the small European countries, in close proximity to large and wealthy markets. But then he argued that we had the good fortune to be part of Asia, and the challenge was how to deepen our integration. Perhaps he needed reminding that (a) most of Asia is still no better than middle income, and (b) all of Asia is a very long way away. In the line Treasury often used to run, draw a circle with a 1000 km radius around Wellington and you get an awfully large number of seagulls and not much else. Draw such a circle around Vienna, Stockholm, or Amsterdam and you capture several hundred million people in wealthy, highly productive, economies.

I also heard a presentation from an Australian academic, Beth Webster, who seemed to see a case for government spending on R&D in principle – since the expected social returns from innovation will typically exceed the private returns. But as her discussion of different types of support schemes proceeded, it wasn’t particularly persuasive that such support actually serves useful ends in practice. And she seemed particularly critical of the competitive grants-based approach the current government has chosen to focus on, noting that heavy reliance on the expertise of evaluation panels (hard in a small country) and the difficulty of ensuring that the grants are actually inducing activity that would not otherwise take place. The incentive on the part of recipients to misrepresent the situation is strong.

The context for all this is that not only is productivity (eg real GDP per hour worked) low in New Zealand, but so is research and development spending (as a share of GDP). No doubt some of the difference is measurement – R&D tax incentives create an incentive to classify more spending as “research and development”, whereas in the absence of such schemes there is not the same reason to bother with isolating out every last dollar. I suspect no one really doubts that business R&D spending in particular is quite low by international standards. But as Adam Jaffe, from Motu, put it, the question is whether that is because the returns to R&D are low in New Zealand, or because there are obstacles to firms undertaking, or commissioning, valuable R&D. Far too little effort seems to have gone into answering that question, even though the different possible answers might have quite different policy implications.

Enthusiasts for governments “doing something” direct on R&D tend to cite “spillover” arguments. Many of the gains from any innovation are not captured by the innovators but by consumers. That reduces the incentive to innovate (at least relative to some unrealistic benchmark). Webster noted we all gain from the wheel, and the descendants of the inventor do not (uniquely). But then look around us, at the enormously sophisticated and advanced society in which we live, and wonder how it all happened, mostly without government R&D grants or tax credits. And then ponder the quality of many, perhaps most, actual – rather than textbook – government expenditure programmes over the years. I’m not persuaded of the case for government support for R&D – at least outside the areas of the government’s own operations (eg defence).

Here is the chart of business R&D spending as a share of GDP, for OECD countries.

New Zealand is towards the lower end, and all the countries to the right of us on the chart are also poorer than us. But I don’t think it is that simple. Formal research work done previously suggests that the rate of business R&D spending in New Zealand partly reflects the sort of stuff we produce. One way to see that is to look the OECD’s commodity exporting countries, and compare them with seven economies at the heart of advanced Europe. These are simply different types of economies.

| BERD (% of GDP) | BERD ( % of GDP) | ||||

| Australia | 1.23 | Austria | 2.03 | ||

| Canada | 0.93 | Belgium | 1.58 | ||

| Chile | 0.14 | France | 1.44 | ||

| Mexico | 0.17 | Germany | 1.96 | ||

| New Zealand | 0.57 | Netherlands | 1.10 | ||

| Norway | 0.87 | Switzerland | 2.05 | ||

| Denmark | 2.oo | ||||

| Median | 0.72 | Median | 1.96 | ||

In passing, it is also perhaps worth highlighting Israel – an economy with very high business spending on R&D, and yet not only an economy with GDP per capita around that of New Zealand, but with a similarly poor longer-term productivity record. They make and sell different stuff – some of which clearly needs lots of R&D – but not, overall, any more successfully than we do.

The 2025 Taskforce addressed some of these issues in their 2009 Report (around p 70). They argued that more attention should be given to the possibility that high levels of business R&D spending might reflect more about where particularly economies are at (near the frontier or not, differences in product mix) rather than being some independent factor explaining the success or failure of nations. In their view, a highly successful New Zealand was likely to be one in which more business research and development spending was taking place, but as a consequence of that transformation rather than an independent cause of it. That still seems like a pretty plausible story to me – although New Zealand is long likely to be primarily an exporter of commodities, and richer commodity exporters (Norway, Australia and Canada) don’t have particularly high levels of business R&D spending.

(And, at the extreme, I checked out the richer Middle Eastern oil exporting countries. Saudi Arabia, Oman, and Kuwait, for example, all have materially higher GDP per capita than New Zealand. World Bank data for total R&D spending have the six OECD commodity exporters spending an average of 1.4 per cent of GDP on R&D, while those three wealthy Middle Eastern countries spend an average of 0.1 per cent of GDP. The point is not that a successful New Zealand will spend at those levels, but that one needs to understand the distinctive features of our own economy.)

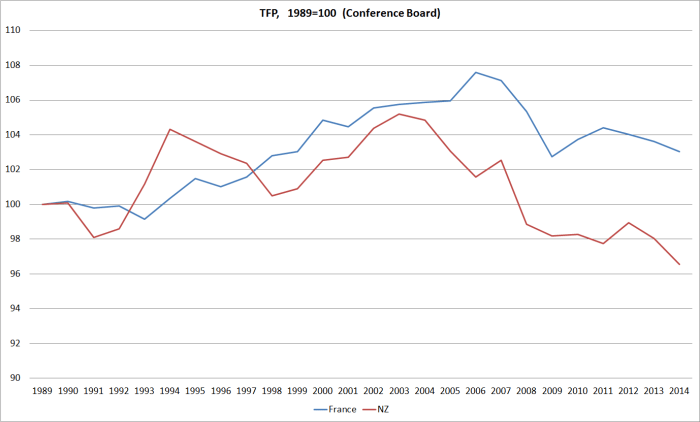

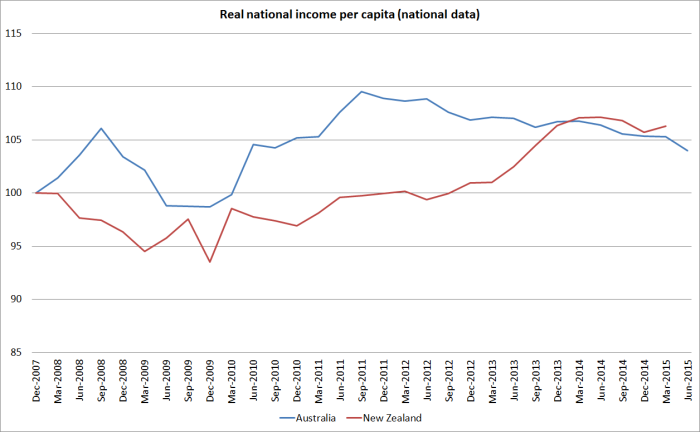

And that sort of perspective was largely lacking from yesterday’s Symposium. I’ve argued for several years that if we want to remedy our economic underperformance, we need to focusing on addressing whatever aspects of policy account for our persistently high level of real interest rates. Real risk-free interest rates are a component of the cost of capital. Ours are higher than those almost anywhere, and that deters investment (and investment-like spending, such as R&D). It has also helped skew our real exchange rate, holding it persistently up, on average, even as the large adverse productivity gap opened. That skews investment (including associated R&D) away from the tradables sector, even though the rest of the world is where most the opportunities would otherwise be. Oh, and we now have a relatively high company tax rate (and tax on capital income) – even though plenty of good economic analysis suggests that capital income should be taxed more lightly than labour income. And yet in the course of yesterday, we heard the Secretary to the Treasury vehemently deny the importance of the real exchange rate, and no one mentioned either the cost of capital or the tax treatment of capital income. Address those issues, and I’m sure we would have an economy much more strongly oriented towards the tradable sector, would have a faster-growing business capital stock per person. And I suspect that we would probably have rather more business R&D spending occurring – the returns to doing it would probably be more attractive.

In a similar vein, I’d commend to readers Terence Kealey’s 2009 book Sex, Science and Profits. Kealey is a professor of biochemistry, and former vice-chancellor of the (private) University of Buckingham. This book builds on his less accessible The Economic Laws of Scientific Research to make the case that science is not typically a public good, and governments do not need to fund scientific research (or, by, implication business R&D). It is a very stimulating read, both on the history of innovation and on the scientific process. I’m sure the bureaucratic tinkerers will have their quibbles with it, but it is an argument that should be engaged with much more seriously by New Zealand official agencies – who need to shift their focus to getting broad government policy frameworks right, and then let businesses take care of themselves. History suggests that when they do so, ingenuity flourishes and societies prosper. Government interventions – mostly well-intentioned, and however cleverly designed – not so much.

The Productivity Hub was an excellent initiative, but they really need to be directing more of their efforts in the direction of the economywide/macroeconomic types of issues. New Zealand is blessed with excellent microeconomic databases – even if they are not always as accessible as they should be – but sometimes data availability determines the direction research takes. I don’t think the case has been made that the real issues that are holding back New Zealand are microeconomic in nature.