One of the odder articles to appear in the local media over the holiday weekend was Fran O’Sullivan’s piece in Saturday’s Herald, headed “Key’s vision: Switzerland south”. I’ve been critical of the Prime Minister in a few posts recently, but when I first saw the O’Sullivan piece I wondered if she was really reporting the Prime Minister or building up a creation of her own. But after several re-readings, I think she must really be reporting the views of our Prime Minister.

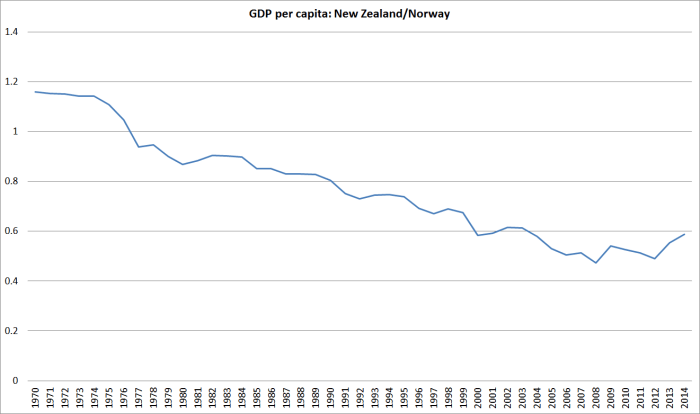

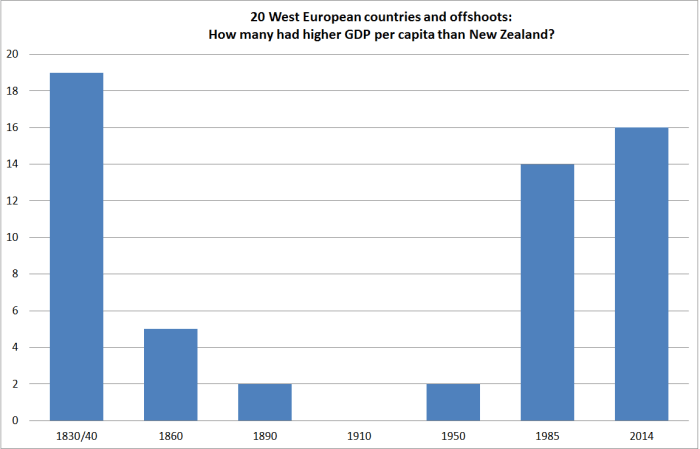

Of course, we have been this way before. In the midst of the 1980s reforms, before the commercial property and equity bubble burst leaving us with a serious financial crisis, people like Michael Fay and David Richwhite used to give speeches talking of building a Switzerland of the South Pacific here in New Zealand. Implausible as it may have been, my memory was of a positive vision – a liberalized economy would stimulate investment and entrepreneurship (and probably a large financial sector led by Fay, Richwhite?), enabling us to generate once again per capita incomes more akin to those in Switzerland(we’d matched or exceeded them as late as the 1920s). In the climate of the times, in the early post-ANZUS days, Switzerland’s armed neutrality probably added to the appealing imagery. Of course, it all came to pretty much nothing. Switzerland remains one of the most prosperous advanced economies, while we languish as the slightly embarrassing poor relation. Fay and Richwhite, as it happens, ended up relocating to Switzerland.

But John Key’s image is a much less positive one – New Zealand as a “beautiful and wealthy bolthole for high net-worthers seeking to escape from an unstable world”.

We are told that

Key believes that free-flowing terrorism is here to stay. To the Prime Minister, this simply makes New Zealand more attractive and will result in more high net-worth consumers wanting to come here

and

But Key contends it is the fear of terror – which has been happening over a long time – which is the driver for Europeans to up sticks and leave.

complete with talk of

If Donald Trump is elected President (assuming he first gets the Republican nomination) there may be a new outflow if his political bombast becomes reality.

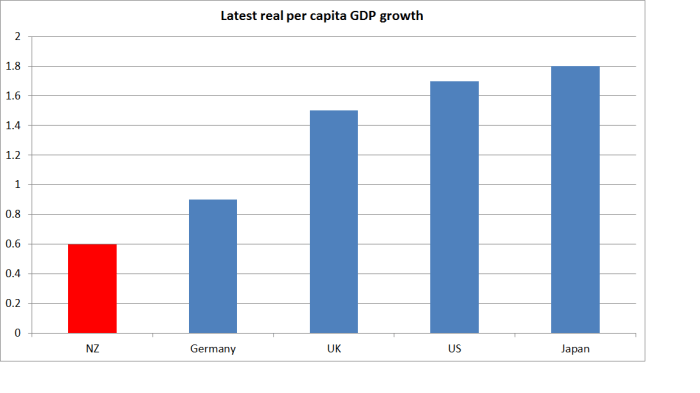

Haven’t we heard all this before? People allegedly about to flee the US if, say, George W Bush was re-elected. Or people fleeing to New Zealand in the 1980s to escape the nuclear peril of the late Cold War tensions. And where are we today? Our per capita incomes and productivity relative to the rest of the world just keep on drifting slowly further behind.

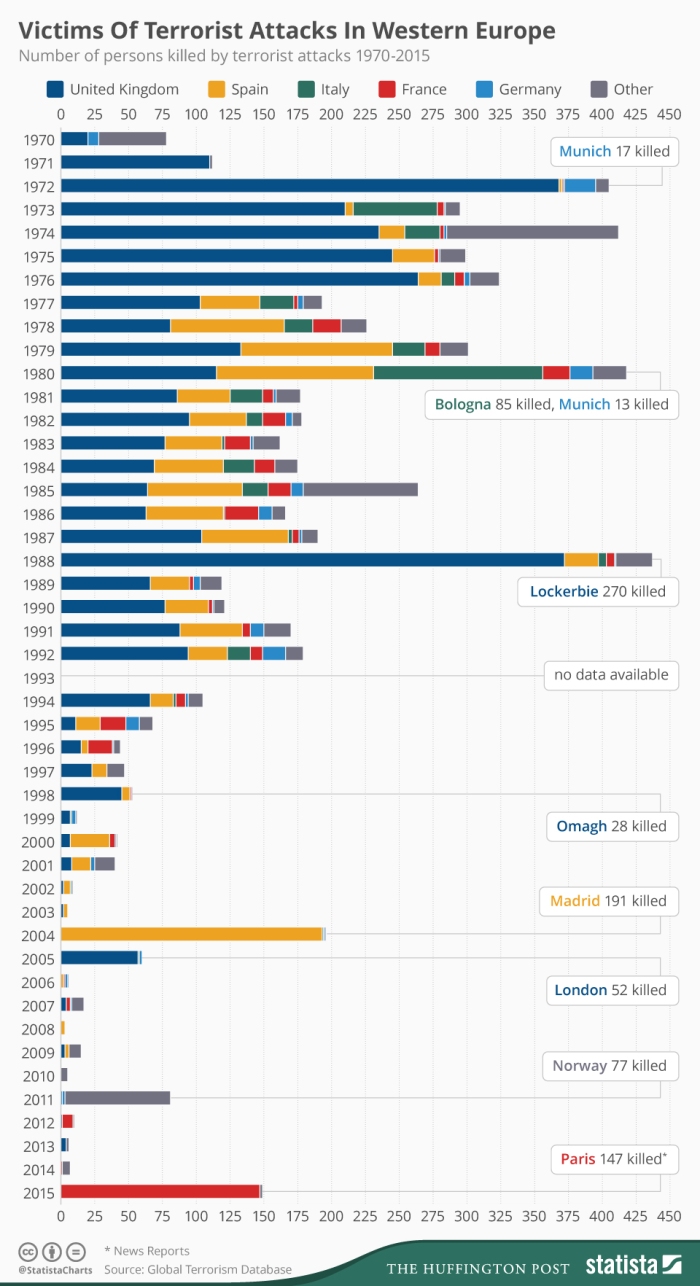

And what about terrorism? Tyler Cowen included a link the other day to this chart of annual terrorism-related deaths in Western Europe since 1970

Hardly a pattern suggesting that the rich and powerful – with much better protections than the masses – should flee to little old New Zealand. If New Zealand didn’t prosper through a century in which Europe went through two savage wars and a prolonged Cold War, an exodus of the elites seems unlikely to be our path to renewed prosperity now.

The great age of European emigration was in the 60 or 70 years prior to World War One, not now.

Ah, but O’Sullivan points out, then there are the Chinese

New Zealand has also become an attractive destination for Asian high net-worthers who have invested in property here – particularly Auckland. Chinese investors are relatively open that they are seeking to de-risk their own exposure to the China market, get capital out and buy residential property in a pollution free environment.

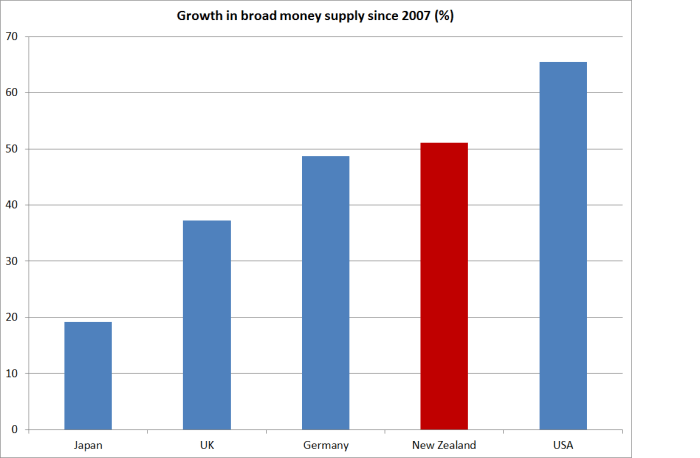

Auckland, and Sydney, and Vancouver, and London and Houston and…..anywhere more or less safe without heavy tax and regulatory restrictions. The Chinese capital outflow story is a real one, and a historically anomalous one – about fear, corruption, and lack of secure property rights in China. But there is little no basis for thinking that it will a basis for transforming New Zealand’s specific economic prospects. We don’t have difficulty attracting foreign capital, but we haven’t (it appears) created a climate in which business investment here is sufficiently attractive to begin to lift our relative productivity and income performance. And as China’s own GDP per capita is about a third of ours, it isn’t obvious that one would look to mainland Chinese as a source of sustained domestic prosperity. (Taiwan or Singapore might be different, but then those countries have rather more respect for domestic property rights and, not unrelatedly, more success in generating domestic prosperity).

And if foreigners really were wanting to build a top-notch global business (as distinct – and it is an important distinction – from protecting what one already had), you almost certainly wouldn’t start from here if you had any other choice. No serious observer ever pretends that New Zealand is better than fifth choice even among the Anglo countries: try the US, the UK, Canada, or Australia, and if you can’t get in there, then there is always New Zealand. For a similar population, higher incomes, and rather better location I’m never quite sure why Ireland doesn’t appear in those lists.

O’Sullivan also tells us tax plays a part. We don’t, she tells, us compete with Switzerland’s (now somewhat attenuated) banking secrecy laws

But it is notable that one of the reasons why New Zealand has yet to follow Australia and bring in rigorous laws to clamp down on multinationals which are not paying significant tax here is because this country is competing for investment.

Perhaps, but this is the same Prime Minister who, interviewed by TV3 a week earlier, reckoned that the tax paid by multinationals in New Zealand was “not fair”, and whose government is part of the OECD-facilitated BEPS process.

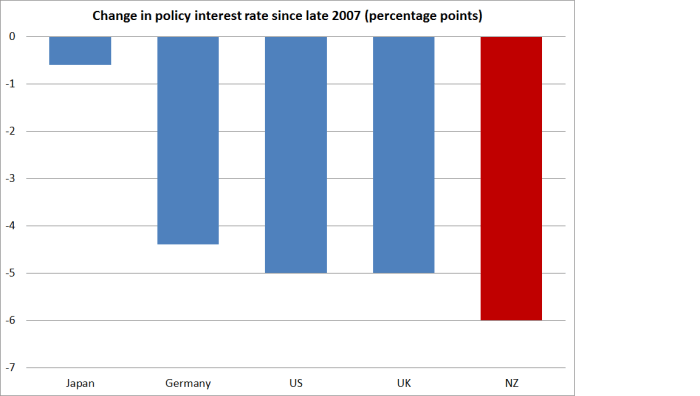

If we were really serious about promoting business investment in New Zealand, and in turning lifting our incomes and productivity performance, one of the best things we could do is to remove taxes on capital incomes altogether. Taxes on business incomes are, largely, taxes on wages, precisely because they discourage the business investment that, for example, New Zealand has been so short of. This isn’t a popular line to run in New Zealand, or perhaps anywhere, but a government that was serious about creating the conditions under which its own people could prosper, and in which foreign investment would assist us in that process, would not still be presiding over a company tax rate of 28 per cent and talking of finding ways to raise more money from foreign companies operating here.

[This is not the post for a lengthy treatment of tax issues, but a standard response is that much lower company tax rates would be a windfall gain to existing foreign investors, with no benefit to New Zealand. That might be so if most foreign investment here were in tradables sectors (since selling prices of tradables are largely determined in international markets), but in fact the largest components of foreign investment here are in the non-tradables sectors, where lower company taxes would be expected to result in lower domestic selling prices (eg for banking or telecoms services), benefiting New Zealand consumers and businesses. I outlined some thoughts on tax a few years ago here.)

As the O’Sullivan moves towards her conclusion she notes

If the Key Government keeps its nerve, the wealth transition will continue. For instance, New Zealand is becoming a magnet for high net-worth Chinese tourists and for students from Saudi Arabia – markets which are growing rapidly. That interest will bring with it investment in hotels, airports, and housing.

Both – Chinese tourists and Saudi Arabian students – are surely welcome, but is there any reason to think they are a probable basis for a reversal of our decades of income decline? Our universities aren’t exactly Harvard or Oxford – or even on a path to getting there – and although I’m loathe to criticize tourism (we want holidays, so do foreigners), there is no advanced country of any size that has managed to support or sustain top-tier incomes based on tourism. France is perhaps the most-visited country in the world, but it isn’t tourism that keeps it rich.

Finally

Annual net migration reached an all-time high of 68,840 people. And net migration from Australia was positive for the 11th consecutive month. These positives underline that John Key’s vision of New Zealand as a Switzerland of the Asia-Pacific has indeed the potential to become reality.

Key won’t be doing anything to destroy that wealth effect.

It gets boring to keep pointing it out, but over the last year around a net 4000 New Zealanders left New Zealand. If we can’t even persuade the New Zealanders to stay, let alone create conditions that make the huge diaspora population want to come back, it is a pretty unpromising foundation for the creation of a Switzerland of the South Pacific.

As for that “wealth effect”, O’Sullivan repeats the claim that the Credit Suisse Global Wealth Report demonstrates that New Zealand households are the second wealthiest (behind only Switzerland). If she got this from Key (with all his advisers) it is inexcusable: the claim was widely reported at the time, but Credit Suisse themselves acknowledged that they had made a mistake, using the wrong exchange rate to convert New Zealand data in to US dollars. I suspect someone else has pointed this out, as the detailed reference in the hard copy edition of the Herald has disappeared from the online version of the article.

It was, in any case, an odd statistic to trumpet. Even on the corrected basis, New Zealand household wealth looks quite high. But it does so because (a) our exchange rate is very high (they use market exchange rates, not PPP ones) and (b) because house prices, especially in the third of the country that is Auckland, are ridiculously high. The average middle-aged homeowner in major cities such as Houston or Atlanta probably has a better house than the average middle-aged Aucklander, but it does not have a $1m price tag attached to it.

Which brings me to my final comment on the article itself. The Prime Minister is reported as

He is frankly unapologetic about the massive increase in Auckland residential property values, which has resulted in many established Aucklanders becoming relatively rich, but younger people being locked out of the market. It is a trend which is not going to stop anytime soon, given the immigration figures.

They aren’t presented as direct quotes but if these lines are representative (and they are consistent with what he said in his TV3 last week) it is surely a disgraceful indictment of a failed government. The sheer indifference to the plight of ordinary New Zealanders is breathtaking. While his government continues to preside over land-use restrictions that limit the ability of Auckland’s physical footprint to grow, then continued high immigration would continue to hold up Auckland house and land prices. But those land-use restrictions could be changed, and should be, especially if we are going to continue with anything like recent population growth rates.

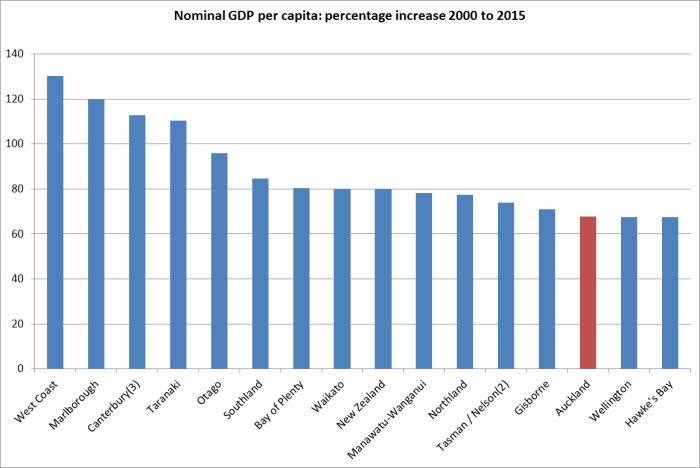

The breathtaking indifference might be slightly less inexcusable if there were any sign that the Prime Minister’s Switzerland “strategy” (or just “this week’s talking point”?) was working. If, for example, incomes were growing rapidly and steadily closing the gap on the rest of the advanced world. But they aren’t. New Zealand continues to do badly, and recent data suggest that over the last 15 years Auckland has done worse than the country as a whole (per capita incomes growing less rapidly).

The Prime Minister is surely mostly right when he says

“They look at us and think it is a highly developed first world economy, unbroken democracy, stable government, independent judiciary

But in Switzerland they get all that, and more. Beauty and stability, rule of law and wealth, and all that in the heart of one of the largest and most populous regions of prosperity and innovation anywhere on earth. Boltholes tend to be places of comfort and luxury but not of great economic dynamism and entrepreneurship. And I’m pretty skeptical that it is “bolthole” tendencies that have enabled Switzerland to get, and stay, rich – that is more down to the innovative products and services of its firms and peoples – but there seems no more basis for thinking that New Zealand is on any sort of path towards being a Switzerland of the South Pacific than there was when Fay and Richwhite were championing the idea 30 years ago.

Countries get and stay rich mostly on the skills and talents and energies of their own people. Natural resources can help. Really remote countries, even with able people and natural resources, face considerable challenges. But to keep on looking for our salvation to come from abroad – as the Prime Minister seems to in this article – seems no more promising than the Melanesian cargo cults.