“I think I can. I …..think ….I…. can, I………… think……… I…………… can” said the little blue engine”

It was almost to the top.

“I——-think”

It was at the top.

“I ———can.”

It passed over the top of the hill and began crawling down the opposite slope.

‘I ——think——- I—— can——I—– thought——I——-could I—– thought—– I—– could. I thought I could. I thought I could.¨ I thought I could.”

And singing its triumph, it rushed on down toward the valley.

“The Little Engine That Could” is a heartwarming childhood tale, about hard work and a willingness to give anything a go. Perhaps the Prime Minister once read the story to his kids. But…….it is a story. Technical capacity, not willpower, determines whether engines can pull loads, get over hills etc. However, the Prime Minister now appears to have adopted the storybook as the basis for his latest, rather desperate, defence of his government’s immigration policy.

At his post-Cabinet press conference on Monday, the Prime Minister appeared to be – as NBR put it – practising his election lines.

Answering questions about New Zealand’s capacity to handle current levels of population growth caused, in part, by very high net migration, English appeared to practice attack lines for the forthcoming election campaign, saying he believed the ability to cope with these challenges was “going to be a key issue in the campaign”.

“We believe New Zealand can adjust to be a growing economy with a growing population,” he said. “Our political opponents think New Zealand isn’t up to it, it’s too hard and the solution is to shut down the growth by closing off international investment, getting out of international trade, closing down migration and settling for a kind of grey, low-growth mediocrity where the best thinking of the early (19)80s sets our political direction.”

and, from another account (which I will draw on but can’t link to)

English said that National unashamedly believes in New Zealand’s capacity to be a growing economy and that its political opponents unashamedly think New Zealand is not up to it.

Belief is one thing. Evidence is (much) better. Winning elections might be a different matter, but whether, and to what extent, large-scale immigration is providing long-term economic benefits to New Zealanders isn’t something to be determined by whose swagger is most convincing; who can put on the most macho stance, or who is most ready to kick sand in the face of the weedy doubters. Wishing for benefits won’t make them happen. Instead, it is a matter of calm balanced analysis and an assessment of the evidence of New Zealand’s experience. We’ve had plenty of experience. And that must be a point of some difficulty for defenders of the current large-scale non-citizen immigration policy, presumably including the Prime Minister.

After all, 100 years ago, on the best available measures, New Zealand had among the very highest material living standards anywhere. Some combination of abundant land, a temperate climate, dramatic reductions in transport costs, and refrigerated shipping had required more people to take advantage of the new opportunities, and enabled just over 1 million people to flourish in what was, by international standards, a highly-productive economy. There were new opportunities here, and it took new people to take earliest and greatest advantage of them.

On some measures, even as late as around 1950 we still had some of the highest material living standards around. There hadn’t been many more new opportunities specific to New Zealand in the previous few decades. But, on the other hand, we’d avoided wars and revolutions at home. It wasn’t much of a surprise that we were still wealthier than almost anywhere in continental Europe.

But mostly since then we’ve been slipping down the rankings, whether measured by productivity (the better measures) or average per capita income (which can always be boosted by working ever more hours). After World War Two, large scale immigration, actively promoted by successive governments resumed. Even then, leading New Zealand economists were sceptical. All manner of arguments were run for actively pursuing increased population. There were defence arguments, there were arguments about redistributing Britain’s excess population to the land-rich Dominions, there was the apparently-reasonable argument that opportunities and incomes were just better here.

But whatever the arguments, any economic gains just seemed to keep failing to show up. Of course, we did lots of daft things during the post-war decades. Trade protection meant that, for example, in the early 1960s we had twenty television factories in New Zealand, and we made or assembled here all sorts of stuff that would never have passed a market test. In the late 70s and early 80s we poured money down the drain in the absurdly expensive energy Think Big projects (while being spared Roger Douglas’s ambition for 16 state-promoted carpet factories). But strip all that stuff away – as we did – and we’ve still done badly.

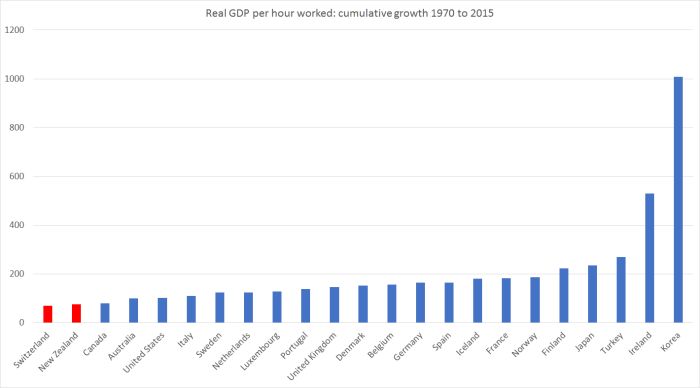

Productivity growth lagged that in other advanced economies in the 1950s and 60s. Since 1970, data suggest that among advanced economies only Switzerland and, perhaps Mexico, have done worse than us. And even since all the reforms of the late 80s and early 90s, we’ve still brought up the rear when it comes to productivity growth. On average, we just keep slipping further behind those other advanced countries we were once so much better off than.

My friends on the right will emphasise how high taxes are, how much wasteful government spending there is, and how pervasive poor-quality regulation is. And I have a great deal of sympathy with many of their individual points. But the median OECD country isn’t really any better or worse than us on those scores (on some we do rather better than the median, on others quite a lot worse). We could all do better, but the explanation for New Zealand’s continuing disappointing performance simply can’t rest in those traditional pro-market verities.

A much more plausible story is one that recognises that New Zealand’s wealth was largely built on able people, and good institutions, making the most of our natural resources. It shouldn’t really be controversial; you can see it in our trade data. As it always was, so it is today – the overwhelming bulk of our exports are the fruits of the land or sea (and I’ll count tourism in those numbers, since that it mostly what tourists come for). Of course, there is small number of successful outward-oriented firms in quite different industries, but strip away the subsidised ones (export education and the film industry) and the numbers are really pretty small.

And not only are no new natural resources being made, but in New Zealand for many decades there hasn’t even been any really large new discoveries of usable natural resources that were hitherto unrecognised (or idiosyncratic shocks that strongly favoured New Zealand production from natural resources). It is, surely, the big difference between the post World War Two experiences of New Zealand on the one hand, and Australia and Norway on the other. The prosperity of all three countries rests largely on the natural resource products their able people, with good institutions, can sell to the rest of the world. Norway and Australia were able to bring to market whole new resources that, while always there, were previously unknown or uneconomic to tap. New Zealand has had nothing similar. No new land, no new sea and – so far – oil/gas and mining activities that are of fairly peripheral scale. If we’d known that difference 50 or 60 years ago, few people (if anyone) would have thought it would make a lot of sense to import lots more people to New Zealand. Combining many more people with a key fixed factor (“land”) is simply a recipe for making it much more difficult than necessary to support top-notch living standards for the people who were already there. And that is so even if one can get lots of productivity growth in the land-based sectors.

Of course, the standard pushback is along the lines of “but that is all old economy stuff; ideas and new technologies are the way of the future, and one can develop those industries anywhere – all that matters is the people, the people, the people”. Which would be fine, but the evidence seems to be against it. When it comes making physical stuff, global value chains have become ever more important, and it is really hard for many firms located at the end of the earth to be part of such value-chains (whereas it is quite easy if you are in Slovakia or Korea). And when it comes to ideas-based industries, counter-intuitive as it might seem, personal connections and proximity (to suppliers, markets, specialist resources, clusters of knowledge) seems to have become more important than ever. All sorts of firms can be set up by people in New Zealand – or in Patagonia, Port Stanley, or Windhoek. But those firms, and those people, will usually command more value relocated nearer those global centres – be they in Europe, North America or East Asia. Wishing it was otherwise – like believing I can fly – simply doesn’t make it so.

New Zealand’s strength is its people, among the most skilled in the world, its institutions (absence of much corruption, rule of law etc) and its natural resources. The latter are crucial – that isn’t something of ideology, or old-school thinking, but of hard numbers – and are, for practical purposes largely fixed. (Add in our (self-chosen) climate change objectives and those natural resource opportunities could almost be argued to be shrinking.) But our disadvantage, and it is a severe one, is distance/location, and at least before teleportation is mastered, that disadvantage isn’t changing – it is a land so remote that until perhaps 200 years ago, there simply was no foreign trade.

Against that backdrop, it is simply crazy to keep letting the central planners (politicians and bureaucrats) try to drive up the population. New Zealanders know it in their own choices. There is nothing shameful about a fairly flat population, whether in a country – plenty of rich European countries have had them for decades – or a city. But it seems almost heretical in New Zealand. It makes sense that cities, or countries, grow when new opportunities abound. The evidence to date strongly suggests they aren’t abundant here. Some might think that a shame – in some ways I do too – but believing otherwise doesn’t make it happen.

Is there 100 per cent conclusive evidence? No, in this life there hardly ever is. But lets look at some of the straws in the wind:

- among the very worst productivity growth in the OECD throughout the post World War Two period,

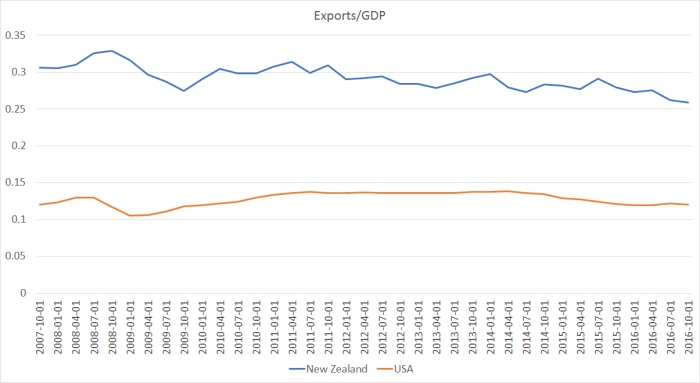

- an export share of GDP that has stagnated and even gone backwards (in a country that once had among the very largest per capita exports anywhere),

- a major city that has incredibly rapid population growth over decades, and yet of which even Treasury now observes “we are not seeing the agglomeration effects we would expect from Auckland’s size and scale.”

I’m for evidence-based policy. If we’d seen more and more New Zealand firms successfully establishing themselves in international markets, and the export share of New Zealand’s GDP rising (as it typically does in successful catch-up economies), if we’d seen a decade of productivity growth materially outstripping that of the other OECD countries so that we were finally catching up, if we are seeing evidence that GDP per growth in Auckland was consistently far-outstripping that in the rest of the country (as we find in many other countries centred on knowledge-based industries) then (a) we could all celebrate, and (b) it might make sense to think about whether we should open our doors to lots of migrants. As it is, we see none of those things. And that with one of the largest (per capita) legal immigration programmes anywhere in the world. It is madness; ideology (“big New Zealand” more than theoretical arguments typically) over experience.

But the Prime Minister and the National Party still “believe” apparently. Perhaps they could show us their evidence?

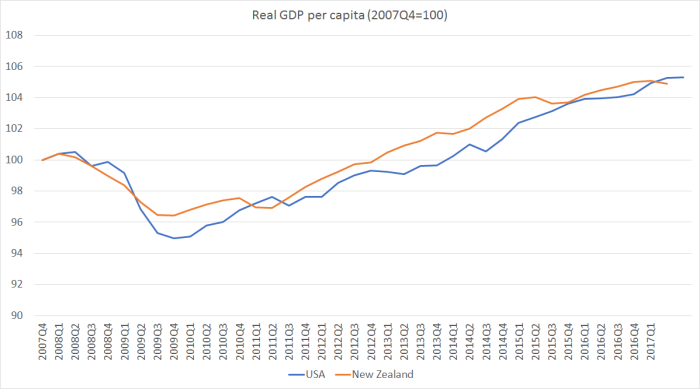

I don’t like to make too much of the last few years’ experience. Apart from anything else, data revisions could mean that stories that look good today eventually disappear like the morning mist. But, for what it is worth, the last few years don’t do much to instill confidence.

There is the dysfunctional housing and land supply market for example. Sure, you can argue that it really has nothing to do with immigration policy, but if you can’t or won’t fix up the land supply market – and neither this government nor its predecessors have – don’t give us the nonsense that New Zealand can cope with his immigration policy. Even if there aren’t large productivity costs from those land-use restrictions (I’m open-minded on that in New Zealand) the distortion to real house prices, that makes purchasing a home more and more difficult in our cities is a standing reproach to our leaders.

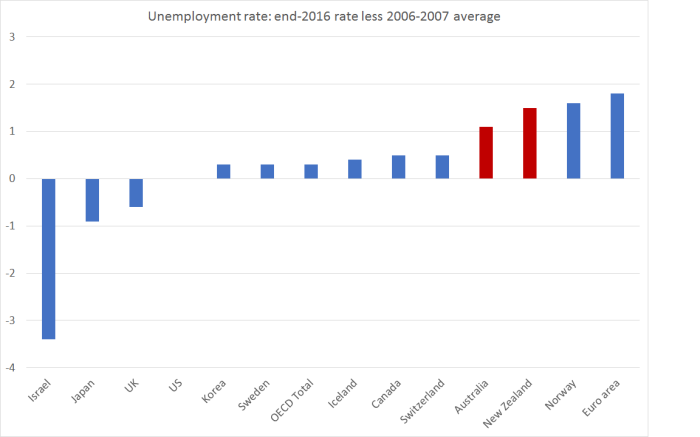

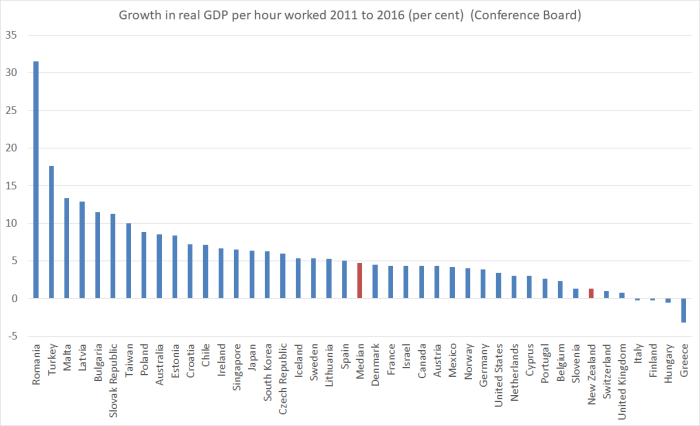

And then there is productivity. I’ve repeatedly showed charts of real GDP per hour worked in New Zealand, where the data suggest we’ve had no growth at all in the last five years (even though the dogma suggests large immigration should be generating positive productivity spillovers). It is often hard to get timely cross-country comparisons, but earlier this month the Conference Board released their latest annual estimates of real GDP per hour worked. Here is how New Zealand has compared over the last five years (2011 to 2016) with a sample of 40 or so other advanced countries (the group I often use – EU members, OECD members, plus Singapore and Taiwan).

And it isn’t just because those other countries were recovering from deeper recessions. Our labour productivity growth also lags behind the median of these countries for the whole period since 2007 (just before the recession). It is just the same old story of underperformance. Are there mitigating factors? Probably always to some extent. The Canterbury rebuild inevitably dragged resources away from other uses. On the other hand, relative to our worst decade of economic underperformance – the 1970s – the terms of trade have mostly been pretty good this decade.

With the export share of GDP drifting further backwards, it looks more and more like an economy that exists on building for each other. Nothing wrong with that in one sense – people need houses, offices, roads etc – but it isn’t how economies successfully catch-up with those richer and more productive than them. That typically involves finding more and better things to successfully take to world markets.

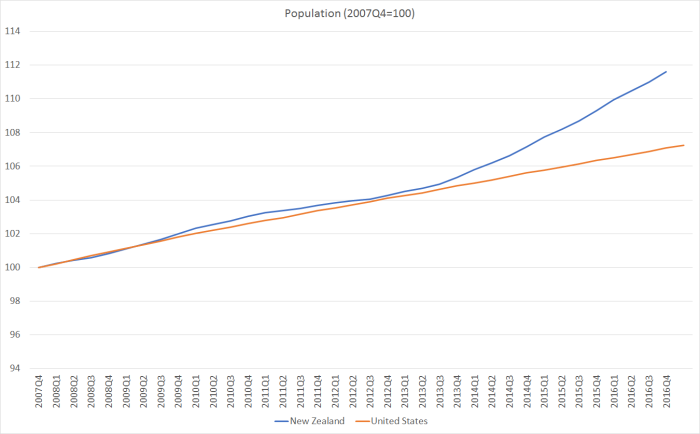

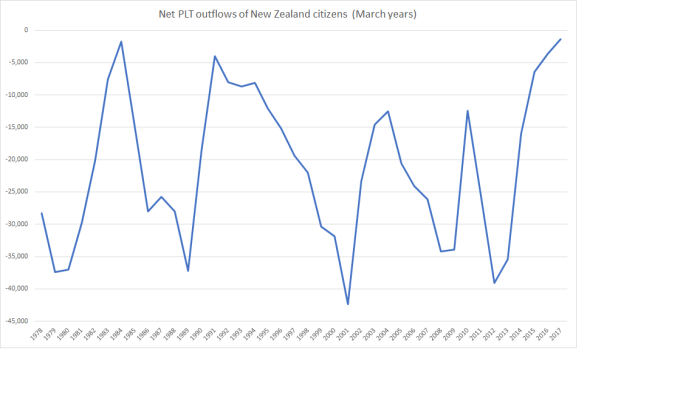

In his post-Cabinet news conference, the Prime Minister was also making much of the contribution to the net migration numbers of the decline in the outflow of New Zealanders to Australia. That, he claimed. “was a vote of confidence in New Zealand”. Perhaps it sounds good politically to say it, but lets face reality. New Zealanders have gone to Australia is fewer numbers mostly because the Australian labour market is tough – the unemployment rate and underemployment rates linger high, and there is increasing awareness of how much on their own New Zealanders are in Australia if things don’t work out well. And even though the labour market is tough, look at Australia’s productivity growth (from a much higher starting point) relative to ours in the previous chart. It isn’t so much a vote of confidence, as an unexpected loss of an escape valve. That makes things even tougher for New Zealand, especially when the government keeps on bringing in much the same number of non-New Zealanders as ever. In the short-term it gives the economy a boost – demand effects exceed supply effects in the short-term – but in the longer-term it just keeps worsening New Zealand’s relative performance on the sorts of economic measures that matter.

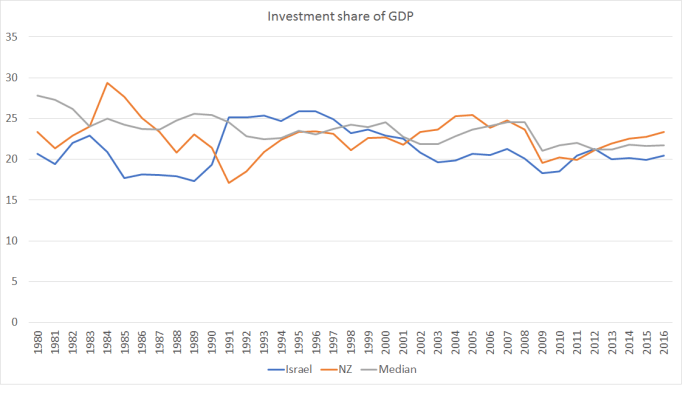

The Prime Minister was also at pains to stress that he believed New Zealand – government and private sector – could and would invest enough to handle the rapid growth in the population. The evidence has long been against him on that one. Despite having had one of the faster population growth rates in the OECD, we’ve long had one of the lower rates of business investment among OECD countries. In a well-functioning economy with high productivity growth etc you’d expect it to be the other way round – more people should need more investment, of all sorts.

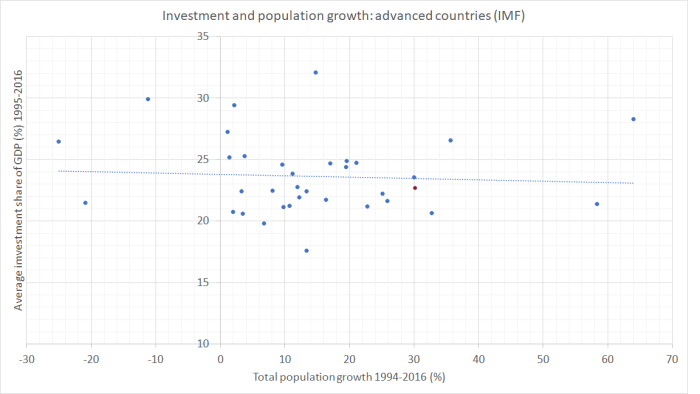

My arguments are generally specifically focused on New Zealand – opportunities in Ireland or Belgium may well be different than in, say, New Zealand, Tasmania or Nebraska. But for what it is worth, here is a scatter plot, using IMF data, of population growth rates and investment as a share of GDP for the countries the IMF classifies as advanced. I’ve used data since 1995, simply because that is the period for which the IMF has data for all countries. Recall that one really should expect investment as a share of GDP to be higher in countries with faster population growth than in those with lower population growth, all else equal.

But

There is almost no relationship at all – and certainly not the expected upward-sloping line. If anything, the relationship is slightly negative. And New Zealand – the red dot above 30 on the horizontal axis – doesn’t stand out from the pack. Since people do have to live somewhere, it looks a lot like rapid increases in population tend to crowd out (rather more price sensitive) business investment. Perhaps it isn’t surprising then that many of the advanced countries with the strongest growth rates in productivity also have flat, or even falling, populations? But, whatever the wider story, there isn’t much reason in the international data to believe the Prime Minister’s wishful thinking that enough will be invested and all will be fine. And when your country already has some of highest real interest rates, and a persistently overvalued exchange rate, it is probably safer to believe that all won’t be just fine.

I could go one, but I just wanted to make two final brief points:

- in his comments quoted earlier the Prime Minister suggested that somehow the alternative to continuing very high immigration targets involved “settling for a kind of grey, low-growth mediocrity where the best thinking of the early (19)80s sets our political direction”. Personally, I’d say the very best thinking from the early 80s – that of reformers at Treasury and Reserve Bank for example – was very much to the point. But even setting that to one side, the Prime Minister’s attempted slur might well rebound. I checked out productivity growth for the nine years to 2016, compared to the nine years to 1984. In those 9 years of Sir Robert Muldoon’s stewardship, growth in real GDP per hour worked was (according to the OECD) 9.0 per cent. Not great. But on the Treasury’s preferred measure of real GDP per hour worked (and even correcting for the break in the series last year), productivity growth from 2007 to 2016, totalled about 5.5 per cent. The Prime Minister was Minister of Finance for most of that period. (Yes, sure there were plenty of other imbalances, bad choices etc then, as well as terrible terms of trade….but they still achieved faster productivity growth).

- I could commend to the Prime Minister a column in The Australian yesterday from Australian labour economist Judith Sloan (there are extracts and commentary on it here). Notwithstanding Australia’s stronger productivity growth, and overall higher incomes, she slams the Australian government’s substantial immigration target (just slightly smaller, in per capita terms, than New Zealand’s), noting in particular the ‘cynical charade’ in professing concern about house prices while doing nothing about immigration (land supply – a major problem in Australia too – isn’t under federal government law). Sloan isn’t just any economist. She led the Australian Productivity Commission 2006 inquiry into Australian immigration. And in many respects, she is about as “right-wing” as they come (to the extent such slogans have meaning), so much so that she was nominated by ACT and the Business Roundtable, and then appointed by the government, to serve on our own 2025 Taskforce a few years ago, where she was instrumental in ensuring that that Taskforce did not champion New Zealand’s immigration policy. She doesn’t write about New Zealand these days, but it would be surprising if her conclusions about our policy were les stridently expressed than those about Australia’s

The Prime Minister can “believe” all he wants. He can attack Opposition parties all he wants (and we have yet to see specifics of what either Labour or NZ First propose), he can diss a former leading figure of the business and economic establishment, Kerry McDonald, he can ignore the counsel of someone as able in this area as Judith Sloan. But what he seems unable to do is offer any evidence that his immigration is, or ever will, work for the benefit of New Zealanders.

There is plenty of cyclical variation, but in both countries on average over this period, the share of investment spending in GDP has been a bit lower than advanced country median. Given all the resources that needed to go to meeting the needs of the fast-growing populations (simply maintaining capital per person), there will have been materially less “left over” for capital deepening, or for new businesses and ideas. It isn’t a mechanical rationing process, but just a response to the opportunities and the relative prices.

There is plenty of cyclical variation, but in both countries on average over this period, the share of investment spending in GDP has been a bit lower than advanced country median. Given all the resources that needed to go to meeting the needs of the fast-growing populations (simply maintaining capital per person), there will have been materially less “left over” for capital deepening, or for new businesses and ideas. It isn’t a mechanical rationing process, but just a response to the opportunities and the relative prices.