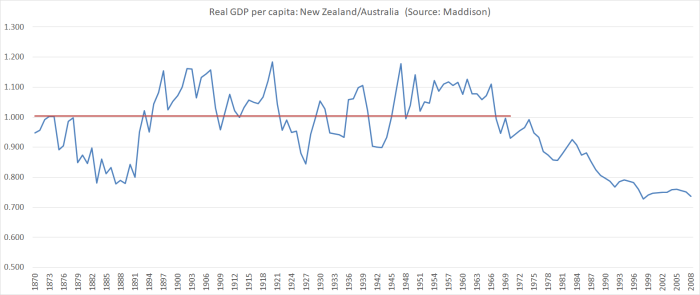

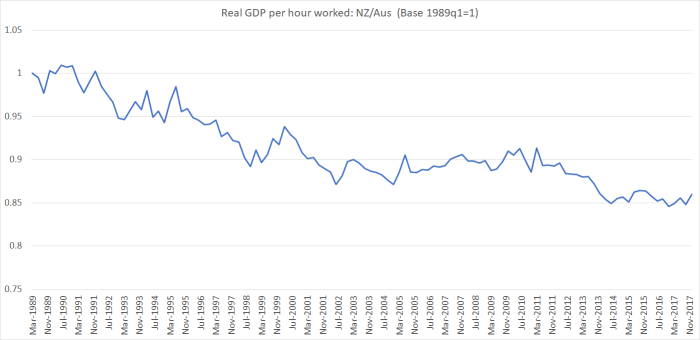

In the minds of members of our new government, much of whatever hope they have of transforming New Zealand’s economic performance (productivity, foreign trade and so on) seems to rest on the proposed R&D tax credit.

Don’t just take my word for that. Yesterday, they released a discussion document on details of the new tax credit, which is scheduled to take effect next year. The document is headed “Fuelling Innovation to Transform our Economy” . In the Foreword, ministers gush

This Government’s vision is to build a better New Zealand for all our people and we see an incredible opportunity ahead of us to do this.

That means a country with affordable, healthy homes; an environment we can be proud to leave to future generations; and a diverse, sustainable, and productive economy that delivers for our people.

This vision can’t be delivered with the same old approaches. We need new ideas, new innovations, and new ways of looking at the world.

And that is where science, innovation and research can play an important role. That is where we see our innovators, our scientists, our entrepreneurs and our visionaries building a better New Zealand.

In the view of the government, businesses don’t spend enough on research and development. They need to spend more. Knowing better than businesses apparently, the government is to fling another subsidy into the mix. My mind is carried back to bad old days of export incentives, and other patchwork attempts to avoid addressing the real issues (in those days, heavy import protection and a (typically) overvalued real exchange rate).

As far as I can see, the only thing released yesterday was the discussion document. There was no officials’ advice on the economics of the proposal, no Cabinet paper, no regulatory impact statement. Not really anything at all, other than few assertions and then straight to the details of the proposed scheme – the only bit they seem actually interested in consulting on. Not once – in yesterday’s document, or in anything else the government has published – have I seen any considered analysis of why profit-maximising firms might have not regarded it as worthwhile to do more R&D spending here. If you don’t understand that, it is unlikely that any proposed remedy is a serious well-structured response. Much seems to rest on the fact that most – but by no means all – OECD countries also offer these subsidies.

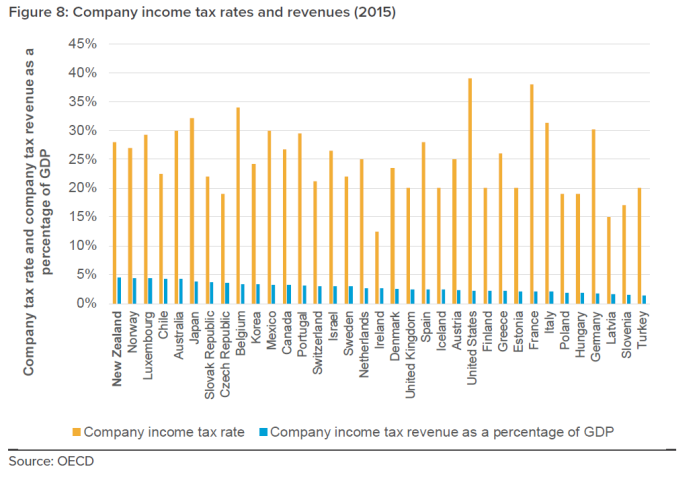

There is quite a reasonable argument to suggest that research and development spending is already rather favourably treated by the tax system. Purchase a physical asset as part of your firm’s production, and you can only deduct it against taxable income through depreciation, over the expected economic life of the asset. But research and development spending is really just another form of investment – it is even in the national accounts (GDP numbers) as such. But most of that spending is immediately deductible for tax purposes. The R&D spending that Boeing did to come up with the 747 generated sales and profits over decades, but instead of that spending being offset against those profits in the years they were earned, it would all have been deductible up-front. The time-value of that favourable treatment is considerable (huge when the R&D leads to a product with a long period in the market). And since New Zealand has now one of the higher company tax rates in the OECD, the value of that standard ability to deduct is already larger here than in many other OECD countries (and before people start invoking our imputation scheme, it is the company tax rate that matters for foreign investors and in the document the government says “We also want to attract large

international R&D intensive firms to New Zealand”).

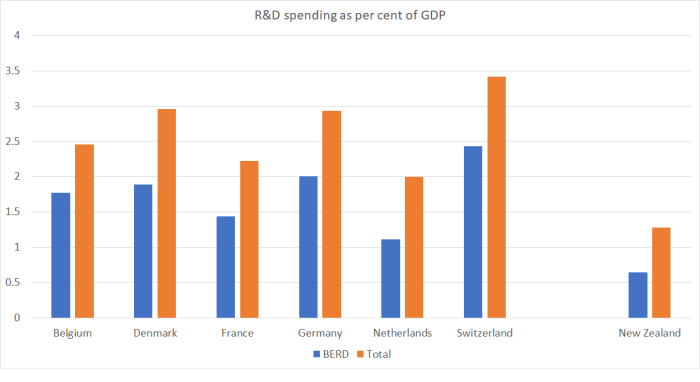

In the discussion document there is a full page graphic highlighting gross R&D spends in a variety of advanced countries. For some reason, even though the R&D credit is aimed at businesses, they don’t quote business R&D expenditure, so in this table I’ve added that column as well, using data from the OECD.

| Total R&D | Business R&D | |

| % of GDP | ||

| United States | 2.8 | 2 |

| United Kingdom | 2.9 | 1.1 |

| Canada | 1.7 | 0.9 |

| Ireland | 1.5 | 1.1 |

| Finland | 2.9 | 1.9 |

| Denmark | 3 | 1.9 |

| Israel | 4.3 | 3.6 |

| Switzerland | 3.4 | 2.4 |

| Australia | 2.8 | 1.2 |

| New Zealand | 1.3 | 0.6 |

Which is interesting, but it is perhaps worth pointing out that of those countries, Finland, Denmark, and Switzerland (as well as New Zealand) don’t have R&D tax credits. As I’ve pointed out in other posts Germany doesn’t either – and business expenditure of R&D there is about 2 per cent of GDP. On OECD estimates, the value of the US tax credit is also very small.

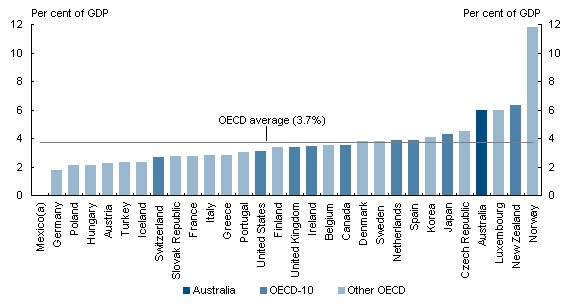

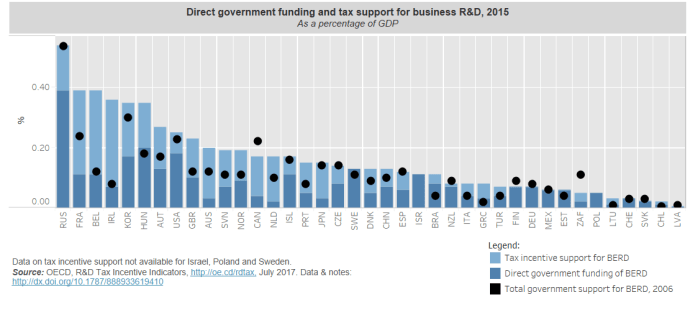

R&D tax credits aren’t the only form of government spending to subsidise business R&D – in fact, the government’s new scheme involves doing away with the current grants. And as it happens, OECD numbers suggests we already spend more (per cent of GDP) on such subsidies than Germany (DEU), and quite a lot more than Switzerland (CHE).

All of which might suggest taking a few steps back and thinking harder about why firms themselves don’t see it as worth undertaking very much R&D spending here. But given a choice between hard-headed sceptical analysis and being seen to “do something”, all too often it is the latter that seems to win out.

In an earlier post, I pointed out

Formal research work done previously suggests that the rate of business R&D spending in New Zealand partly reflects the sort of stuff we produce. One way to see that is to look the OECD’s commodity exporting countries, and compare them with seven economies at the heart of advanced Europe. These are simply different types of economies.

BERD (% of GDP) BERD ( % of GDP) Australia 1.23 Austria 2.03 Canada 0.93 Belgium 1.58 Chile 0.14 France 1.44 Mexico 0.17 Germany 1.96 New Zealand 0.57 Netherlands 1.10 Norway 0.87 Switzerland 2.05 Denmark 2.oo Median 0.72 Median 1.96 In passing, it is also perhaps worth highlighting Israel – an economy with very high business spending on R&D, and yet not only an economy with GDP per capita around that of New Zealand, but with a similarly poor longer-term productivity record. They make and sell different stuff – some of which clearly needs lots of R&D – but not, overall, any more successfully than we do.

A reasonable counter to this sort of line of argument might be “ah yes, but we want to be Denmark – after all, in some sense they once were New Zealand (agricultural exporter etc)”. But if the opportunities are really here for such a transformation, has the government and its advisers stopped to think about why firms don’t seem to see investing in more R&D as offering a worthwhile expected return? Danish firms didn’t seem to need an R&D tax credit to get there.

Personally, the 2025 Taskforce’s approach to the issue seems more persausive

The 2025 Taskforce addressed some of these issues in their 2009 Report (around p 70). They argued that more attention should be given to the possibility that high levels of business R&D spending might reflect more about where particularly economies are at (near the frontier or not, differences in product mix) rather than being some independent factor explaining the success or failure of nations. In their view, a highly successful New Zealand was likely to be one in which more business research and development spending was taking place, but as a consequence of that transformation rather than an independent cause of it. That still seems like a pretty plausible story to me – although New Zealand is long likely to be primarily an exporter of commodities, and richer commodity exporters (Norway, Australia and Canada) don’t have particularly high levels of business R&D spending.

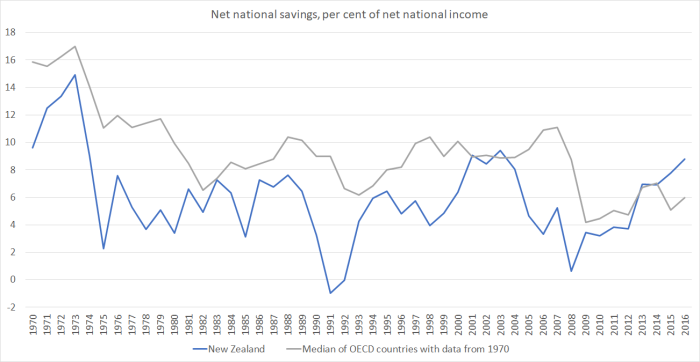

And part of the transformation in New Zealand seems almost certain to involve a much lower real exchange rate for a prolonged period. It was an important message in the 1980s – when officials actually took it seriously – and remains no less important today, even if ministers and officials now seem to ignore the issue.

I don’t want to spend time on the detailed issues of the design of the new tax credit. But I did notice this

A business will need to spend a minimum of $100,000 on eligible expenditure,

within one year, to qualify for the Tax Incentive. The rationale for setting the threshold at $100,000 of eligible expenditure is to filter out claims that are not likely to be genuine R&D. $100,000 of expenditure is roughly the cost of one full time employee’s salary and related overhead costs.

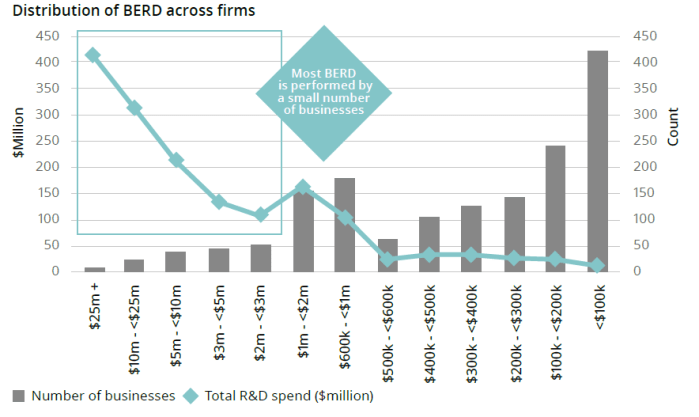

It isn’t clear why small claims should be less likely to be all genuine R&D than large ones. But then juxtapose the planned threshold with this chart

In other words, a large proportion of the companies doing R&D won’t be eligible for the new subsidy at all, while the “big end of town” can gobble up generous subsidies from the taxpayer. It is corporate welfare, deliberately skewed to the bigger firms.

An interesting feature of the proposed new tax credit is that there is no attempt to structure it to incentivise increased levels of R&D spend. The tax credit will apply to the first dollar of R&D expenditure (for firms above the $100000 threshold) – much of it spending the firm would have done anyway. No doubt there are arguments for such an arrangement in practicality and minimising compliance costs. But it also means that the returns to whatever additional R&D spend might take place as a result of the tax credit will have to be very high, to cover the cost of the whole programme. And yet there is no attempt at any sort of cost-benefit analysis (actually not even an estimate of the fiscal cost) in the discussion document – or even a hint that one has been done elsewhere. It is as if the government believes that any increase in recorded deductible gross R&D spending will offer gains in material living standards for New Zealanders. Perhaps, but it would be nice to see the case rigorously made, and the detailed assumptions exposed to scrutiny.