In my post last Thursday I offered some thoughts on changes that should be initiated by the government in the wake of the Governor’s surprise resignation. (Days on we still have no real explanation as to why he just resigned with no notice, disappearing out the door and (eg) leaving his international conference in the lurch, but this post is entirely forward looking.) Here I want to elaborate on three points, having benefited from a few days to reflect and a few useful conversations/exchanges:

- the position of the Board chair, Neil Quigley,

- policymaking on bank (and related) regulatory matters,

- the Funding Agreement.

Board members, including the chair, of the Reserve Bank cannot be removed at will by the government. That puts them in a different position than the boards of many other government agencies. Whatever the pros and cons of that model (and there are both) it is the law as it stands.

Last year the government – for reasons never made clear – extended the term of the chair of the Board, Neil Quigley, for another and apparently final two year term. Quigley has been on the board for a very long time now, and has been chair since 2016. By usual standards of corporate governance that would really be too long anyway, even allowing for the fact that the role has changed over time. But it was pretty clear when the reappointment was done last year that with Quigley getting another two years but Orr having (then) almost four years to run, the government expected – and appropriately so – that a new chair would be in place to lead the search for, and transition to, a new Governor (Governors are now limited to two terms).

It should be untenable for Quigley lead the search (and transition) process now. He drove the selection and appointment (and reappointment) process for Orr in the first place. And frankly, however Orr appeared to the interviewers in 2017, that did not turn out well, and did not end well. The Board – and especially the long-serving Board chair – has to take some responsibility for that (including the chaos of last week, including Quigley’s own unconvincing belated press conference, which one person put it to me was bad enough to warrant dismissal for cause – sadly, not really a statutory option). In addition, Quigley – whose responsibilities have been to the public and the minister – has had the back of the Governor throughout his term, and there has never been the slightest hint in any Board Annual Report of any concerns at all. Worse, it appears that Quigley championed that blackball back in 2018 which – unlike any serious central bank in the world – saw anyone with current or future research interests in or around monetary policy banned from consideration for appointment to the Monetary Policy Committee (and yes, there is chapter and verse on this). Much more recently, whether deliberately or through careless forgetfulness (and failing to check records) he actively misled Treasury and, in turn, the public on this matter, claiming there’d never been such a ban (see, eg, here and here).

It is time for Quigley to go, and for cleaning house to begin in earnest. Quigley can’t be dismissed, but it shouldn’t be beyond the wit of the Minister of Finance to have it made clear to him that it isn’t tenable or appropriate for him to lead the next stage. Quigley himself is a wily political operator and could no doubt read tea leaves were they presented to him. And he seems still to want that medical school. Willis also has an existing board vacancy to fill now, and 2 more positions become vacant on 30 June.

(Assuming she isn’t willing to amend the Act to make the appointment of the Governor wholly a choice for her and the Cabinet), Willis should be looking to move in short order to put in place a new Board chair, someone not compromised by the Orr years, someone of stature (appointments need to be consulted with other parties in Parliament), but also someone trusted to be sympathetic to the general direction the government wants to go with the Bank. (If that seems threatening or politicised, it isn’t intended that way, but we are a democracy and governments, in Parliament, get to make the big picture policy and organisational directional calls). In any case, the Minister should look to issue a new letter of expectations to the Board making clear what she is looking for as regard budget discipline, policy priorities, and the qualities to be sought in a new Governor.

What about prudential regulatory policy? In most areas of government, policy is set by ministers, and implementation is done by agencies, including Crown entities, operating (implementing/applying) at arms-length from ministers. That is both efficient (ministers have limited time etc) and consistent with good governance generally – we really do not want ministers playing favourites for their donors or mates in the application of the standard rules, and we really do want accountability to Parliament and public for policy choices.

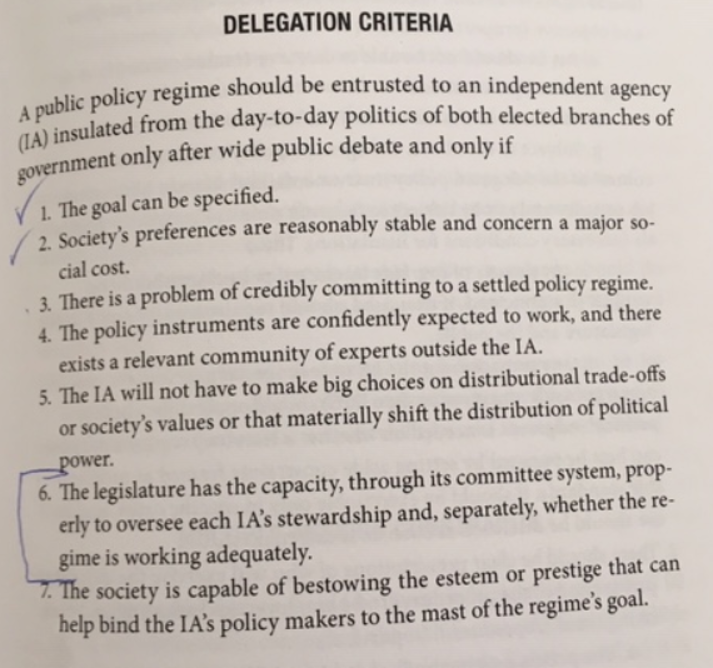

In prudential policy in New Zealand things are different. For the most part, the Reserve Bank itself gets to set the rules (big picture social risk tolerances and all) and apply them. Prudential regulators of course tend to like such a model, and there is plenty of literature from sympathetic former regulators, and from academics, in support of it. On the other hand, it looks pretty dubious through a democratic accountability lens. I’ve written here previously about former Bank of England Deputy Governor Paul Tucker’s book on delegating power, including but not exclusively so, to central banks. Bank regulatory policy simply does not pass the test – the various sensible principles Tucker lists – for being delegated to technical experts. And, as it happens, in New Zealand the power doesn’t even rest with technical experts, but with the Reserve Bank Board, which has been very light indeed on expertise or experience in these areas.

It has become clear that the government is unhappy with elements of Reserve Bank policy choices in these areas. Some of the apparent discontent – eg last year and the secretive advice re remuneration of settlement account balances – doesn’t make sense. Some other counts seem weak, and others rather more persuasive. But here’s the thing: the government is the government and, hand in hand with Parliament, is supposed to make our laws, and be accountable for them. The government, for example, sets the inflation target (while delegating OCR calls needed to deliver inflation near target).

It seems highly likely that prudential policy issues are going to be front of mind in choosing a new Governor (all that ongoing select committee inquiry and all). Which is fine, but a much more direct way to do things would be to seek a simple amendment to the Deposit Takers Act to make clear that in setting prudential standards the Reserve Bank first needs the consent of the Minister of Finance (at present, the Bank needs to inform her – not consult – and even failure to inform doesn’t invalidate the new rule). Then the government could be confident that whoever became Governor would be (a) providing advice, and b) ensuring the implementation of the rules, but that policy itself would be being set by the government. People we can toss out. We shouldn’t want a yes-man (or woman) as Governor – it shouldn’t be in the Minister’s interests either – and it is critically important that the Minister gets robust, technically expert, advice from the Bank (informed by research and critically-reviewed analysis) before making prudential policy decisions. But big picture policy calls should be for the Minister.

I’m not a parliamentary process expert so perhaps it might take a few months to make such an amendment. It is likely to take a few months to appoint a new Governor anyway, but any appointment could then be made with the new Governor knowing that those would be the terms on which they were taking the job.

The final of my three points is about the Funding Agreement, widely believed to be one of the factors that led Orr to storm off. As a reminder, the Reserve Bank isn’t (but probably should be) funded by annual parliamentary appropriation (yes, we want operating autonomy but we still fund the Police that way), but through an agreement that determines how much of its profit the Bank gets to keep and spend. This is a deeply flawed model – a legacy of late eighties disputes. Not only does Parliament not get a say at all (with hundreds of millions of operating spending involved) but the Bank does (government departments simply get told by ministers what their appropriation will be). But worse it is not compulsory for there even to be a Funding Agreement, and the law states that if there isn’t one the board simply has to use its best endeavours to keep spending no more than in the last year of the previous agreement. Which, I suppose, caps further growth in bloat and budget, but could be used to simply to refuse to accept a cut in budgets (when almost every other government agency has had or faces cuts). I’m not suggesting the Bank would negotiate in bad faith, but….the law is the law, and it gives them much more power and formal leverage than most agencies have. It should be changed, and in short order, to ensure that if the five year funding model remains, a) the Minister sets the amount, and the allocation among Bank’s statutory functions, and b) that all is subject to parliamentary debate and ratification as other government spending is.

Changing tack, who might eventually be chosen as the new Governor? There isn’t any obvious standout candidate – which may be a poor reflection on how our system has worked, including the way successive Reserve Bank Boards have operated over the last couple of decades. Various articles have listed a reasonably predictable list of possible names, including Arthur Grimes, John McDermott, Christian Hawkesby, and Prasanna Gai [UPDATE: and Dominick Stephens was also on those lists]. I tossed into the mix on Twitter the other day the name of former Government Statistician and (more recently) Deputy Governor, Geoff Bascand. One name I have been a bit surprised not to have seen mentioned – casting the net necessarily wide – is Carl Hansen, who was appointed to the MPC last year, but who has both Reserve Bank and Treasury experience, and chief executive experience.

All those people are economists by background. Neither the current head of the Fed nor the current head of the ECB is an economist. That is pretty uncommon these days, but both the Fed and ECB have deep benches of economics expertise in very senior roles. But might, for example, there be a case for a strong non technically expert change manager becoming Governor, perhaps with the intention of doing only 2-3 years (on the pattern of Brian Roche at PSC)? I’d be wary – perhaps a good Board chair could best do some of that – but….there is no standout candidate.

An obvious question is what about New Zealanders abroad or indeed foreigners (eg the Australian government has appointed a Brit, with no past ties to or experience of Australia, to the Deputy Governor role at the RBA). I used to be pretty staunchly opposed to a foreign appointment when the Governor was the all-powerful single decisionmaker, but legislative reforms have – at least on paper – spread the power. Someone with no past ties to, or experience of, New Zealand would still face a big adjustment hurdle, and it would be quite risky (and there are adverse selection issues: the most able globally might reasonably think their best opportunities were not in New Zealand). New Zealanders abroad might be more of an option, although one I used to champion as warranting serious consideration (including in 2017) – David Archer, former Assistant Governor, former senior official at the BIS – might have almost aged out by now (although is probably only about the same age as Grimes) and has been away for a long time. There will be others.

I’m not going offer my thoughts on the pros and cons of any of these individuals. Suffice to repeat that, and especially given the broad role as it is currently specified, there doesn’t seem to be a compelling candidate in any of the lists. Perhaps even more than usually, in coming up with their final pick, the Board and the Minister might want to be thinking in terms of a team at the top, the sort of people a possible new Governor would choose to fill the couple of most senior posts (policy and operational/administrative) around him/her.