Reserve Bank Deputy Governor, Grant Spencer, gave another speech on housing yesterday. I was pretty critical of his previous effort (here and here).

The latest Spencer speech has some interesting material in it. But too much of what he is saying doesn’t seem to be based on any substantial research or analysis. A good example is around tax. Apparently the Bank now regards”tax policy as an essential part of the solution, given the historical tax-advantaged status of investor housing”. But if it is an essential part of the solution why are they content with such modest changes? And what has happened to previous Bank analysis suggesting capital gains taxes would have little sustained effect on house prices? Grant Spencer has neither presented, nor referenced, any analysis that supports either limb of his statement. Indeed, previous Reserve Bank work, done by someone who now works at the heart of the Bank’s regulatory interventions, showed that to the extent that the tax system favoured housing, the greatest biases (by a considerable margin) were in favour of the unleveraged owner-occupiers. That work was done in 2008, and since then the tax situation of investor property owners has become relatively less favourable, because of the depreciation changes in 2010.

And yet there is not a mention in the speech of the awkward issue of tax on imputed rents on owner-occupied houses[1]. As I noted yesterday, the Bank seems to have adopted a disconcerting style of endorsing whatever measures the government of the day is happy with, and staying quiet on other aspects of policy that might directly affect house prices (eg first-home buyer subsidies, large scale active immigration programme, arguments about stamp duties for non-resident buyers, and the non taxation of imputed rents). That sort of pandering has become too common in government departments, but shouldn’t be the standard adopted by an independent Reserve Bank.

There is lots in the speech I could comment on. But I want to focus mainly on one of my perennial issues, the stress tests undertaken by the Reserve Bank and APRA last year, and reported in the November Financial Stability Report. As regular readers will know, faced with a pretty severe test:

- real GDP falling 4 per cent,

- house prices falling 40 per cent (and 50 per cent in Auckland) and

- the unemployment rate rising (by more than it has in any floating exchange rate post-war country) to 13 per cent.

banks came through largely unscathed. Loan loss expenses peaked at around 1.4 per cent of banks’ assets (compared to a peak of around 0.8 per cent in 2009). That seemed like the basis of a pretty sound financial system. Don’t just take my word for it: in the FSR the Reserve Bank itself observed “the results of this stress test arereassuring, as they suggest that New Zealand banks would remain resilient, even in the face of a very severe macroeconomic downturn.”

The Reserve Bank Act allows the Bank to use its regulatory powers to “promote the soundness and efficiency of the financial system”. How, I have asked, could further highly intrusive restrictions be warranted when the system was so sound, especially as such restrictions have inevitable efficiency costs? For quite a while, we got nothing in response from the Governor and his staff. The Governor simply avoided answering a direct question on the issue at Parliament’s Finance and Expenditure Committee – even though the Bank has often argued that the Governor’s appearances at FEC are a key part of the accountability framework.

The Reserve Bank finally addressed the issue in the consultative document, released on 3 June, on the proposed investor property finance restrictions. This was what they had to say.

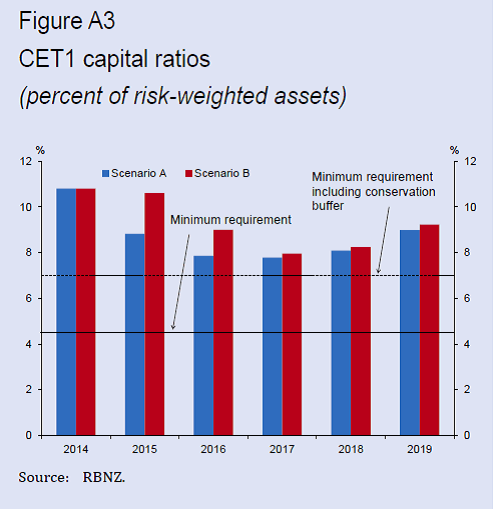

The Reserve Bank, in conjunction with the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority, ran stress tests of the New Zealand banking system during 2014. These stress tests featured a significant housing market downturn, concentrated in the Auckland region, as well as a generalised economic downturn. While banks reported generally robust results in these tests, capital ratios fell to within 1 percent of minimum requirements for the system as a whole. Since the scenarios for this test were finalised in early 2014, Auckland house prices have increased by a further 18 percent. Further, the share of lending going to Auckland is increasing, and a greater share of this lending is going to investors. The Reserve Bank’s assessment is that stress test results would be worse if the exercise was repeated now.

We don’t know what other submitters made of this argument, but in my submission I argued that this was both a weak and flawed claim. Weak, in that there is no claim that the results would be “materially:, “significantly” or “substantially” worse. And flawed in that higher asset prices would, all else equal, provide a larger equity buffer in the event of a subsequent fall.

In its response to submissions, released last Friday, the Bank went some way to acknowledging this point

It is true that rising house prices do not immediately increase the risks of losses in a stress test. Indeed any given percentage fall in house prices will leave house price levels higher in absolute terms if house prices have risen further prior to the downturn (so someone borrowing years prior to the downturn may still have substantial equity). The Reserve Bank is mindful, however, that gross housing credit originations are substantial (in the order of 30% of the outstanding stock of housing credit each year). So elevated levels of house prices tend to lead fairly quickly to higher levels of borrowing and debt to income ratios for many borrowers. Additionally, if house prices rise further relative to fundamentals they are likely to fall further in a downturn.

But again this is misleading. The statistic that 30 per cent of the stock of housing credit is newly originated each year tells us nothing about risk. A borrower shifting his or her (otherwise unchanged) debt from one bank to another will be captured in the Reserve Bank’s gross originations data, but that shift does not change the risk in the banking system. Overall, debt is growing very sluggishly, and the Bank has still not given us a single historical example where a banking system has run into crisis when for the previous several years the stock of the debt had been growing no faster than nominal GDP. In principle, too, a higher peak of prices might suggest a larger fall, as the Bank says, but they already allowed for a 40 per cent fall, and a 50 per cent fall in Auckland, and I’m not aware of any historical case in which house prices have fallen much more than 50 per cent.

So far, so unconvincing. But in his speech yesterday, Grant Spencer took a new and interesting tack on stress tests. Here is what he had to say

There is a point to clarify here around the stress testing that the Reserve Bank conducts on the banking system as part of our prudential oversight function. Sometimes commentators incorrectly interpret the aim of macro-prudential policy as preventing bank insolvency. From a macro-prudential perspective, we may wish to bolster bank balance sheets beyond the point of avoiding insolvency. Stress tests help to inform our assessment of the adequacy of capital and liquidity buffers held by the banks. However, they are only one of the tools contributing to that assessment. In a downturn, banks will typically become risk averse and start to slow credit expansion in order to reduce the risk of breaching capital and liquidity ratios. In a severe downturn, faced with a rise in impaired loans and provisions, banks may start to contract credit which can quickly exacerbate the economic downturn. In this way, a financial downturn can have severe consequences for macro-financial stability well before the solvency of banks becomes threatened.

In 2014, the four largest New Zealand banks completed a stress testing exercise that featured a 40 percent decline in house prices in conjunction with a severe recession and rising unemployment. While this test suggested that banks would maintain capital ratios above minimum requirements, banks reported that they would need to cut credit exposures by around 10 percent (the equivalent of around $30 billion) in order to restore capital buffers. Deleveraging of that nature would accentuate macroeconomic weakness, leading to greater declines in asset markets and larger loan losses for the banks. Such second round effects are not reflected in the stress test results. A key goal of macro-prudential policy is to ensure that the banking system has sufficient resilience to avoid such contractionary behaviour in a downturn.

I suspect that Grant has my comments in view here. Actually, I had long assumed that the Reserve Bank did not aim to prevent all bank insolvencies – the official line, after all, has long been “we don’t run a zero failure regime”. Prudential policy has avowedly been aimed to reduce the probability of an institution failing, but not to prevent all failures. That seems to me like the right public policy approach.

But I have also assumed that the aim of prudential measures (call them “macro-prudential” if you like, but there is no distinction in the Act) was to promote the maintenance of a sound and efficient financial system. Why? Because that is what the Reserve Bank Act, passed by Parliament, says the Bank is to use it powers to do. It is not clear that the Bank has any statutory mandate for actions motivated by a “wish to bolster bank balance sheets beyond the point of avoiding insolvency”, and especially not when there is apparently no regard being paid at all to the efficiency of the financial system.

Anyway, Spencer goes on to argue that the real purpose of the controls – whatever the Act says – is to avoid banks contracting credit in a severe downturn. But actually in a severe downturn – and especially one associated with a prior credit and asset price boom of the sort the Deputy Governor worries about – some contraction of credit seems like a good and desirable outcome. No doubt it would be unhelpful if the doors was closed to all loan applications, but no adjustment process ever occurs perfectly or costlessly. In fact, as the Reserve Bank noted in its discussion of stress tests in the FSR last November, “it can often be difficult to implement mitigating actions in the midst of a severe crisis”, and as a result “the Reserve Bank’s emphasis tends to be on ensuring that banks have sufficient capital to absorb credit losses before mitigating actions are taken into account”.

Spencer worries that a material deleveraging could exacerbate the extent of the fall in GDP and asset prices, and the rise in unemployment, worsening the credit losses relative to those highlighted in the stress test scenario. That is a plausible argument in principle, but it drives us back to the question of how demanding were the stress test scenarios in the first place.

I’ve already mentioned how demanding the unemployment component of the stress test was. No floating exchange rate country since World War 2 has had an increase in the unemployment rate as large as implied in the Reserve Bank tests. Countries are typically much better able to adjust to shocks if the exchange rate floats, than if they are fighting to defend a fixed exchange rate . Interest rates can be cut further and with fewer constraints, and the exchange rate itself can fall, a lot.

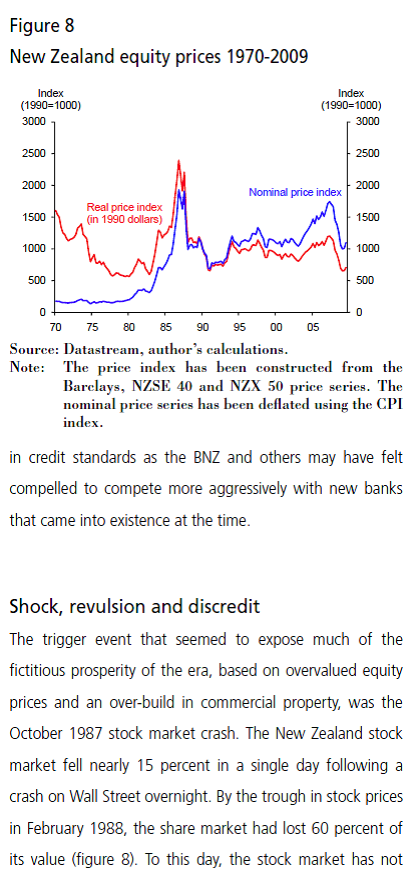

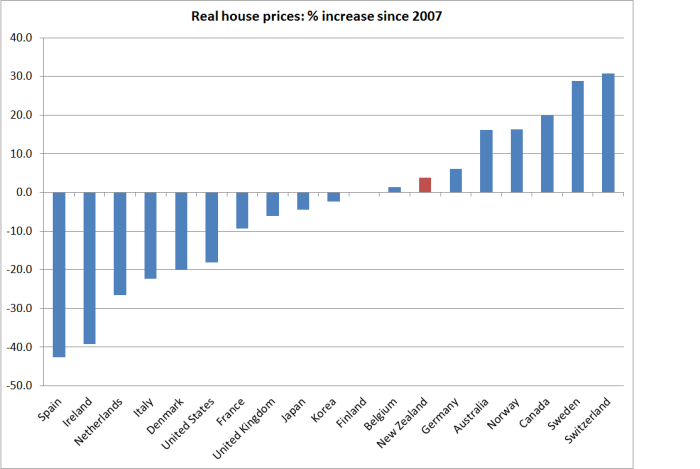

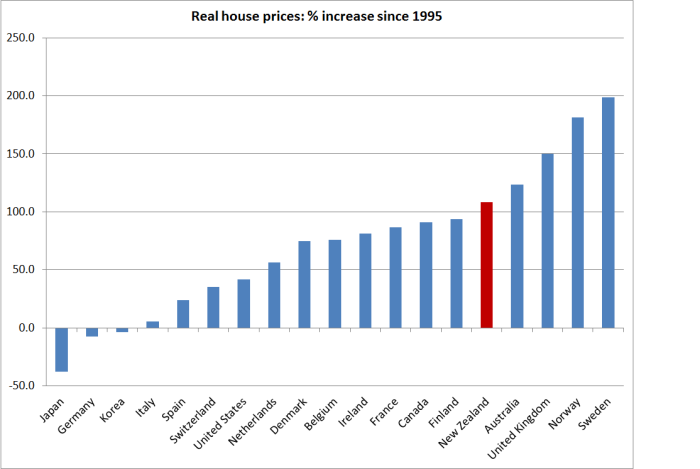

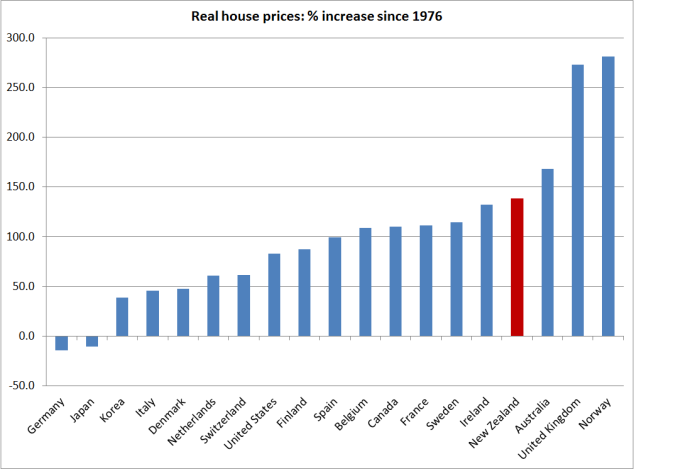

The Reserve Bank used a scenario in which nationwide house prices fell by 40 per cent, and Auckland prices by 50 per cent. Since 1970 I’ve found only been six episodes in which advanced country real house prices have fallen by more than 40 per cent (the stress tests rightly use nominal house prices, so a 40 per cent fall in nominal house prices is a more demanding test than a 40 per cent fall in real prices).

Five of those six cases occurred in countries with fixed exchange rates. In only three of those cases was there a material fall in GDP, but the falls that did happen were very large: Finland’s GDP after the 1989 house price peak fell by 10 per cent, Ireland’s GDP after the 2006 house price peak fell by 9 per cent, and Spain’s GDP after its 2007 house price peak fell by more than 7 per cent[2]. Based on historical experience, to get an increase in the unemployment rate from around 5 per cent to 13 per cent, and a more than 40 per cent nationwide fall in nominal house prices, it would probably take more a more severe recession than a 4 per cent fall in GDP. US real (altho not nominal) house prices fell by almost 40 per cent in the late 00s, but even there the unemployment rate did not rise by as much as is assumed in the Reserve Bank of New Zealand’s stress tests. Losses on mortgage portfolios mostly arise from the interaction of falls in nominal prices and sharp rises in the unemployment rate.

What do I take from that? If the stress tests have been done robustly – and no one has raised serious substantiated doubts about that, the scenario probably already implicitly reflects any short-term deepening of the recession that might result from any active deleveraging banks might undertake. Banking crises everywhere – Finland, Spain, Ireland, Norway, Korea, Japan (and the United States) – has seen some deleveraging, and the effects of that are reflected in the historical data.

I welcome the attempt to address the stress tests directly, and to attempt to defend current policy against the results of that work. But it still doesn’t seem to stack up. The Reserve Bank has a statutory mandate to use prudential powers to promote the soundness and efficiency of the financial system. The Bank’s own numbers suggest the system is sound “even in a very severe macroeconomic [and asset price] downturn”, and direct controls have real and substantial efficiency costs which the Bank just does not address. And cyclical stabilisation is primarily a matter for monetary policy, a point the Deputy Governor also does not address.

This post has gone on long enough, so I’m going to largely skip having another go at Spencer’s unsubstantiated enthusiasm for high-rise apartments, pausing only to note that his continued enthusiasm for the number of apartments in Sydney – where land use restrictions are even tighter than in Auckland – , reads rather oddly given that Sydney is one of the few cities with higher house price to income ratios than Auckland. I have no problem if people want to live in apartments – laws should allow them to be built – but I’m not sure there is any good basis for the Reserve Bank Deputy Governor to be trying to dictate people’s housing choices. There is plenty of land in New Zealand.

And, finally, I was struck by Grant’s observation that housing issues keep the Reserve Bank “awake at night”. He went on to note that “when something keeps you awake at night, it is good to do something about it”. Perhaps. Sometimes, it might be good to get up, read a book for half an hour and go back to sleep. If my kids wake with a bad dream, I give them a hug and send them back to bed. Focusing on the facts can also be a way of dealing with the night worries. Avoiding too much caffeine and rich food can help too.

Lying awake at night can induce tiredness and irritability, reducing one’s ability to analyse issues clearly. The Reserve Bank has offered lots of snippets of information, and lots of prejudices, but very little sustained analysis on the nature of the risks to the soundness and efficiency of New Zealand’s financial system. As someone put it to me yesterday, it is also a very macroeconomic speech, conveying little sense of what is going on in domestic credit markets. I suggest the Bank should focus again on the stress test results, and the very demanding assumptions used in those tests, keep a close eye on credit standards, and that they then look to monetary policy to do the cyclical stabilisation job. The price of financial stability is constant vigilance, but the Bank still looks as though it is jumping at (financial stability) shadows. Their own earlier hard analysis suggests a pretty robust financial system, no matter the insanity of the mix of other policies that is producing house prices as high as they now are in Auckland. That is a measure of the success of the Reserve Bank – charged by Parliament with financial system soundness and efficiency, not house price stabilisation – not the basis for a need for ever more costly and inefficient interventions.

(And in case any of this sounds complacent, I suspect I’m much more worried about the New Zealand and world economies right now than the Bank has given any hint of being.)

[1] I don’t necessarily favour such a change, but then I don’t think tax issues play a material role in explaining house price behaviour in New Zealand.

[2] In Korea nominal prices fell gradually during the real economic boom of the 1990s, in Japan nominal prices fell for 20 years, without a very severe recession, and in Norway in 1980s there was also no substantial recession. Both Norway and Korea had fixed exchange rates through most of these periods.