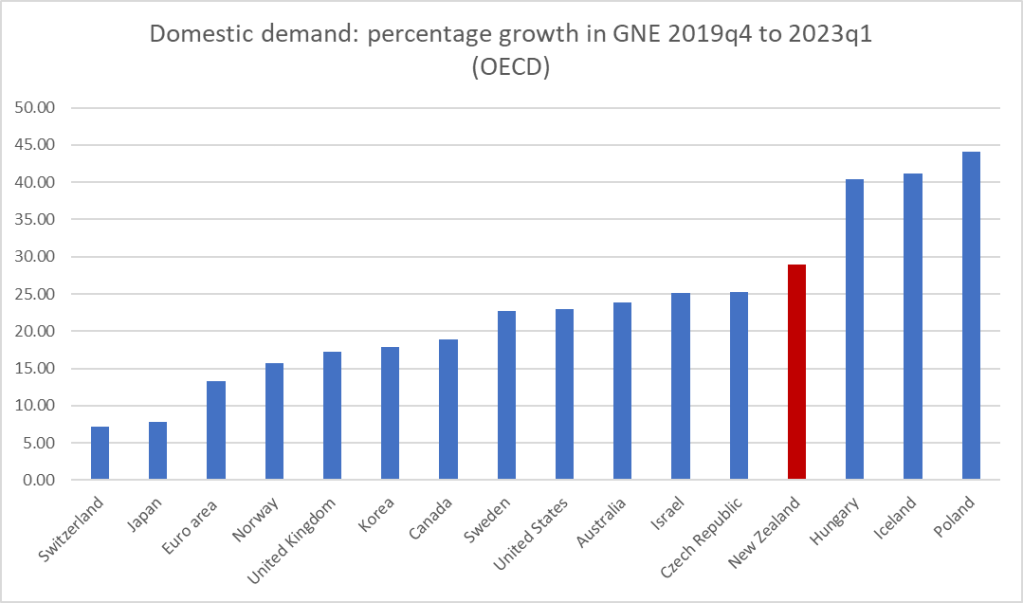

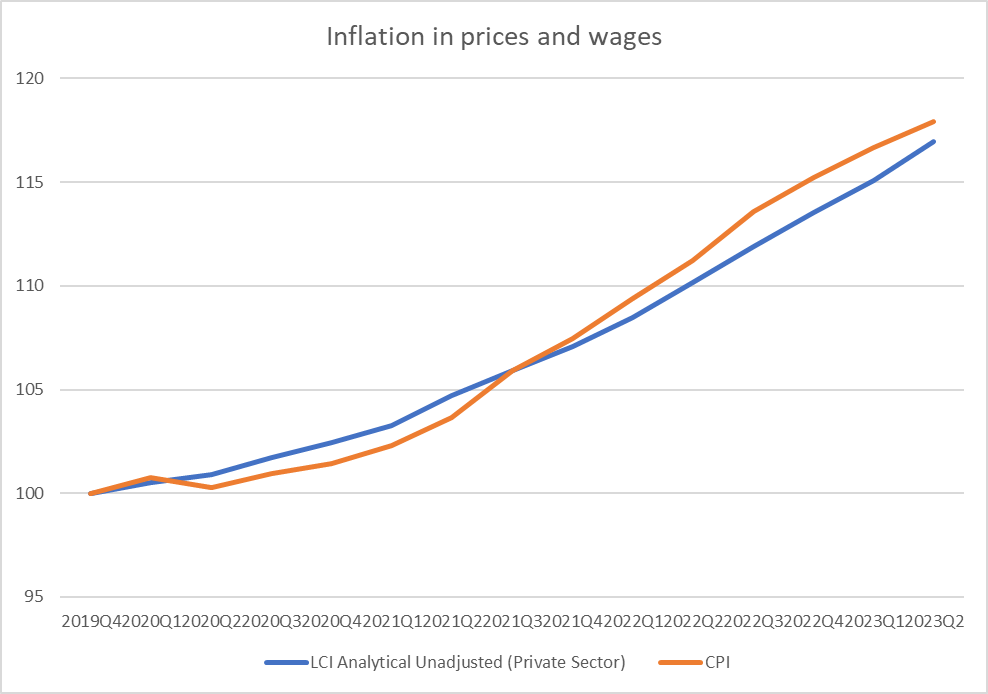

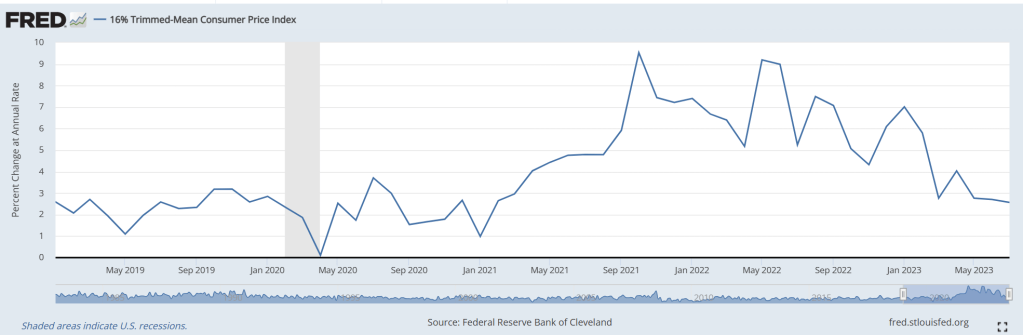

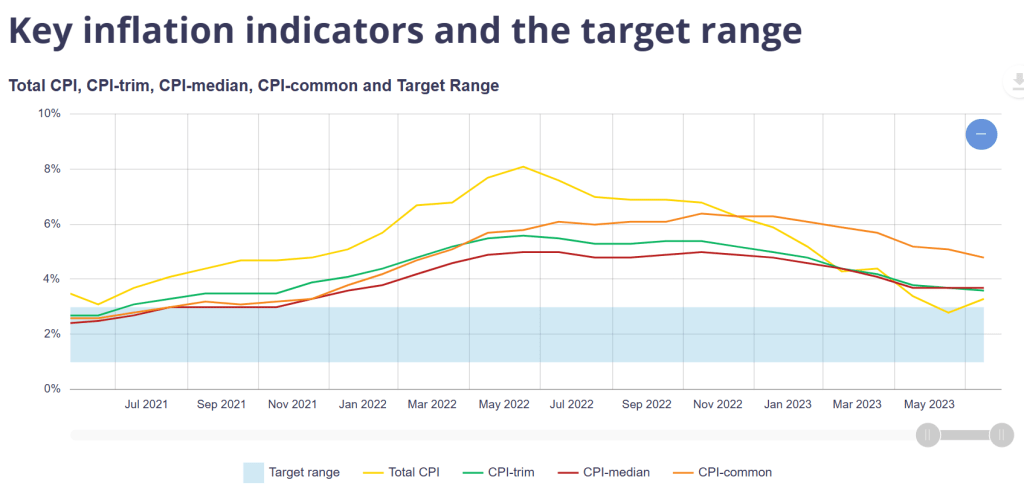

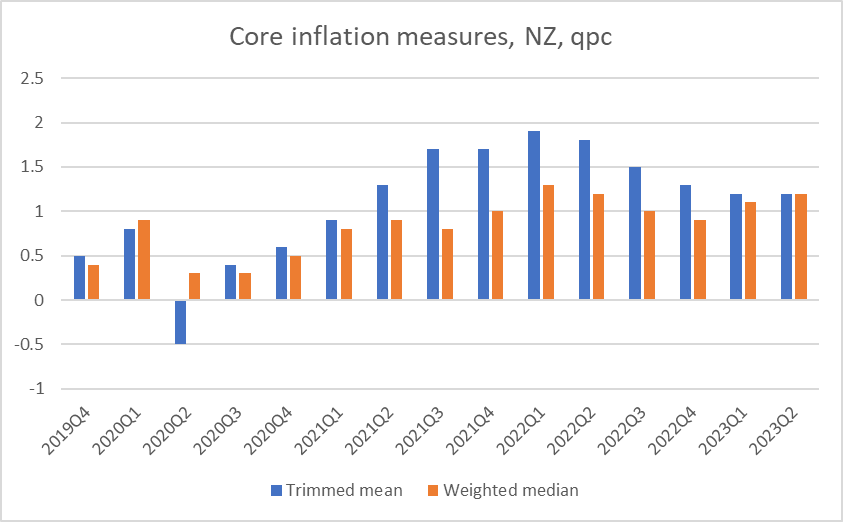

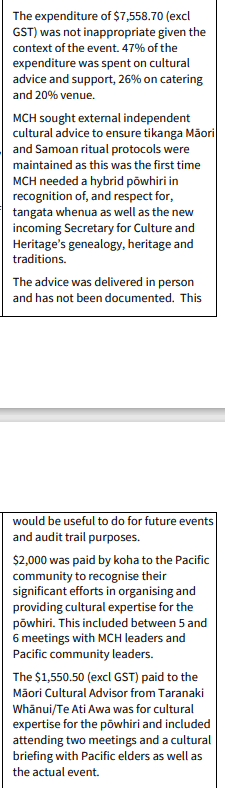

I’ve used this chart before to illustrate how diverse the (core) inflation experiences of advanced economies have been in this episode. It isn’t as if they’ve all ended up with similarly bad inflation rates, and the point of focusing on those countries with their own monetary policy and a floating exchange rate is that core inflation outcomes are a result of domestic (central bank) choices (passive or active) in each country.

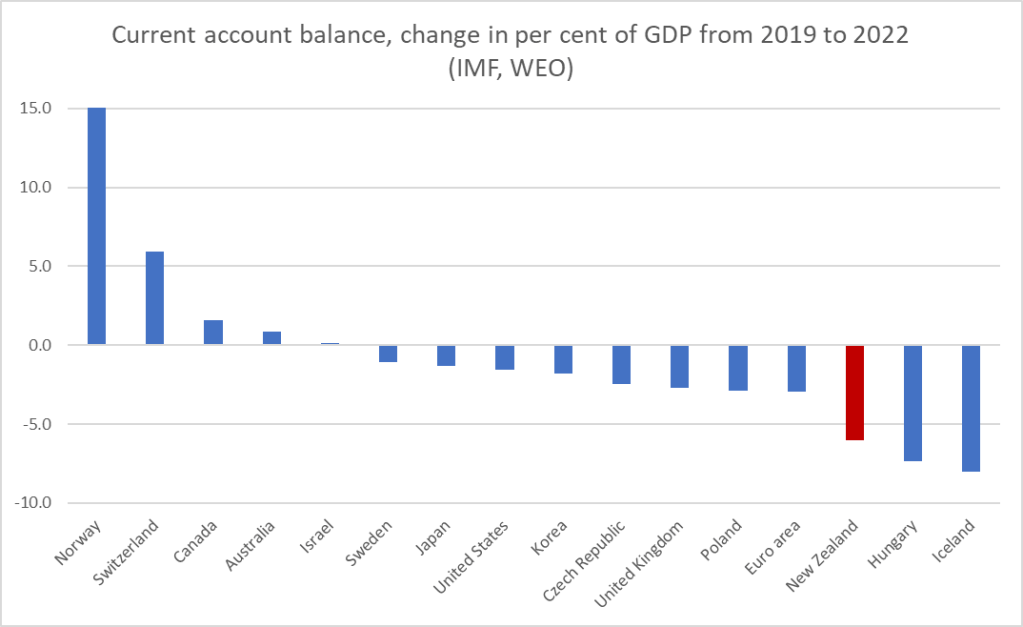

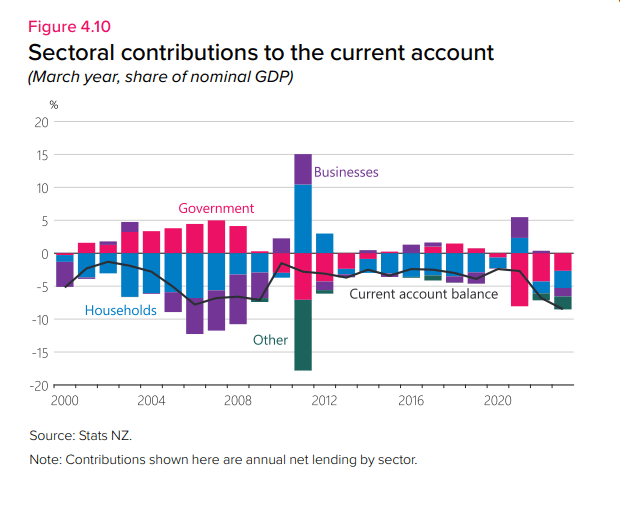

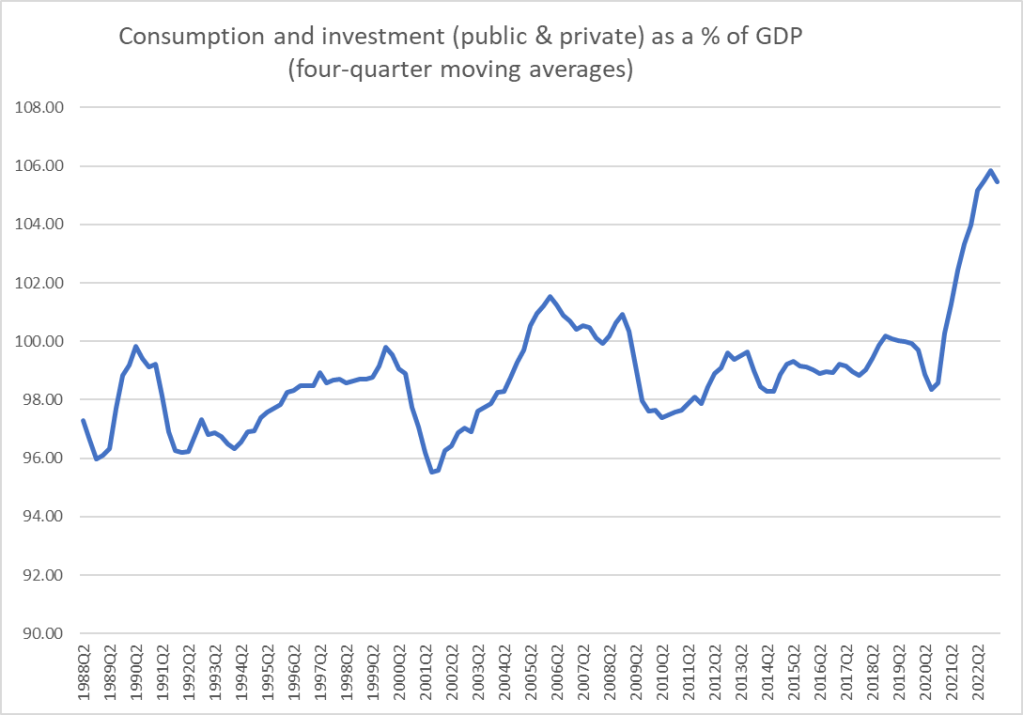

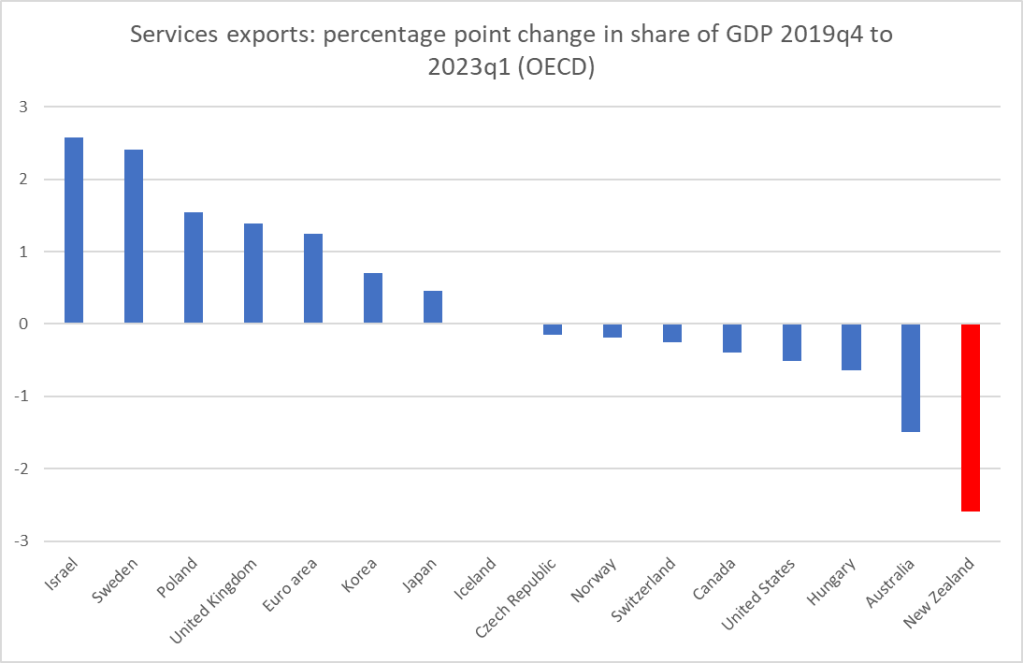

Yesterday’s post focused on the rapid growth in domestic demand that the Reserve Bank had facilitated and overseen. But, it might have occurred to you to ask, what about foreign demand? It all adds up.

And if you look more broadly you might reasonably have thought New Zealand would be a good candidate for being towards the left-hand end of this chart.

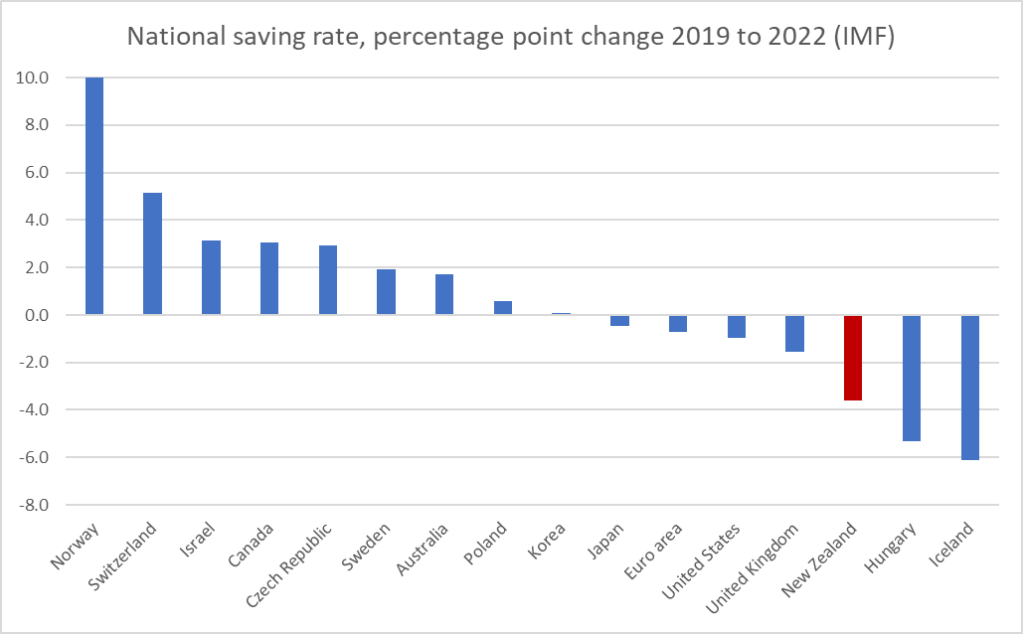

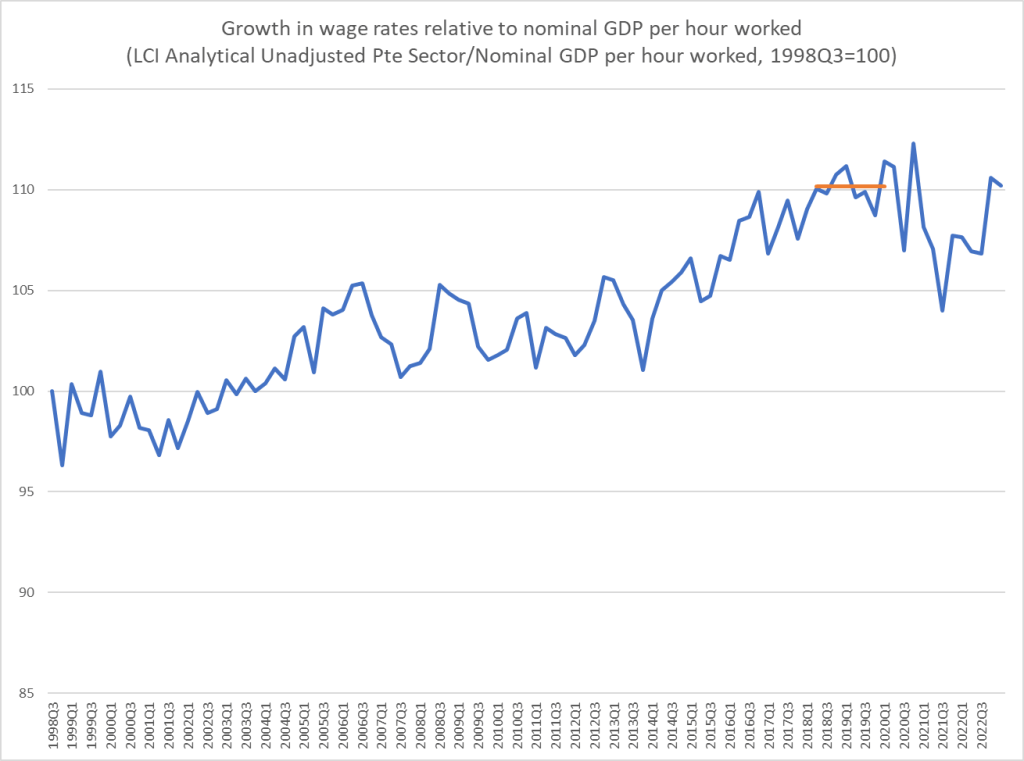

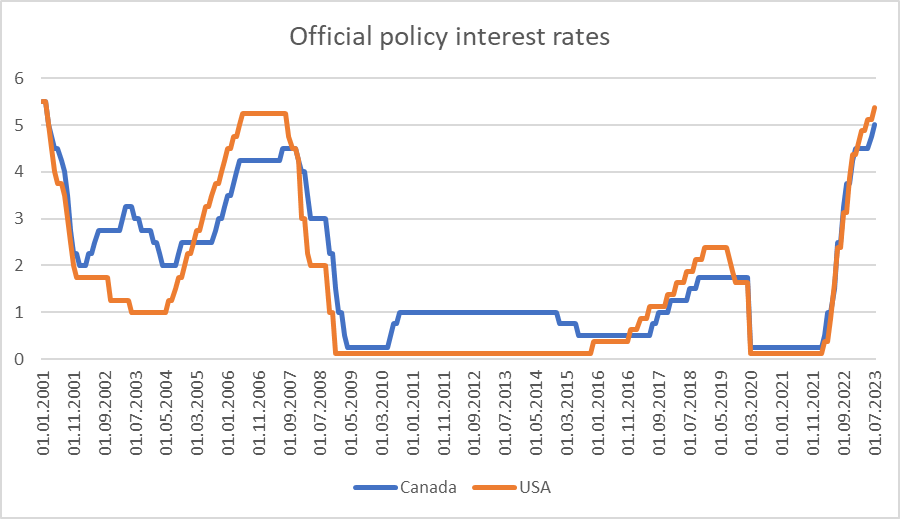

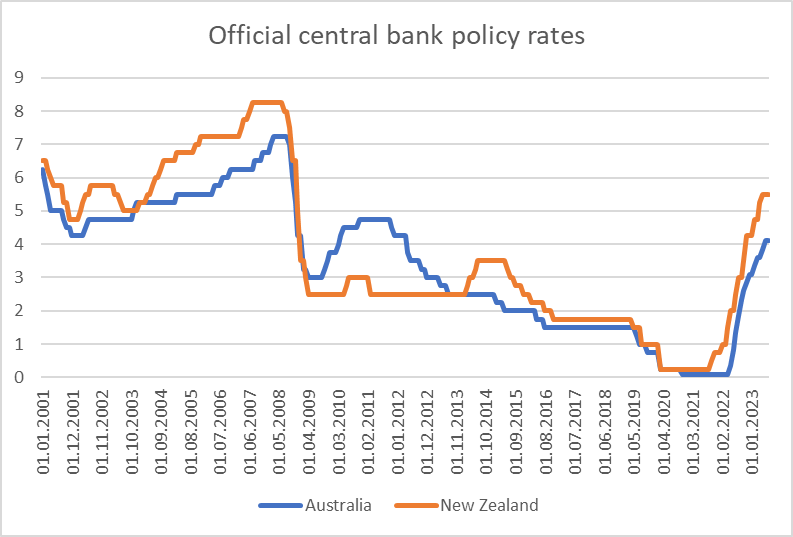

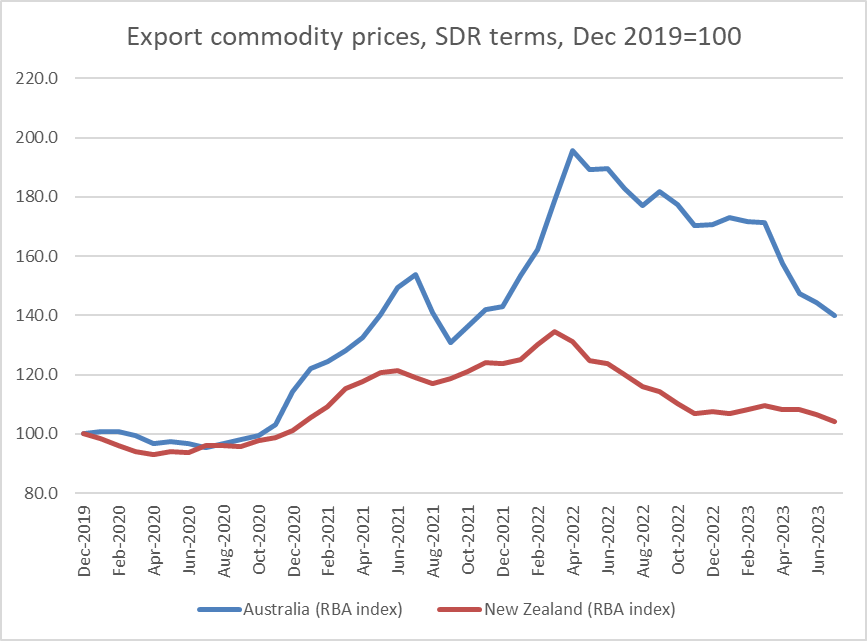

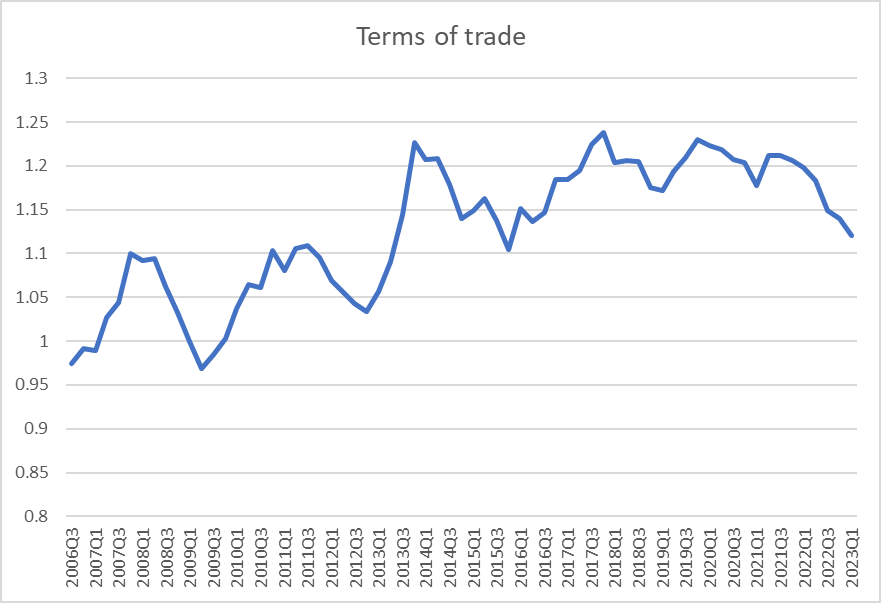

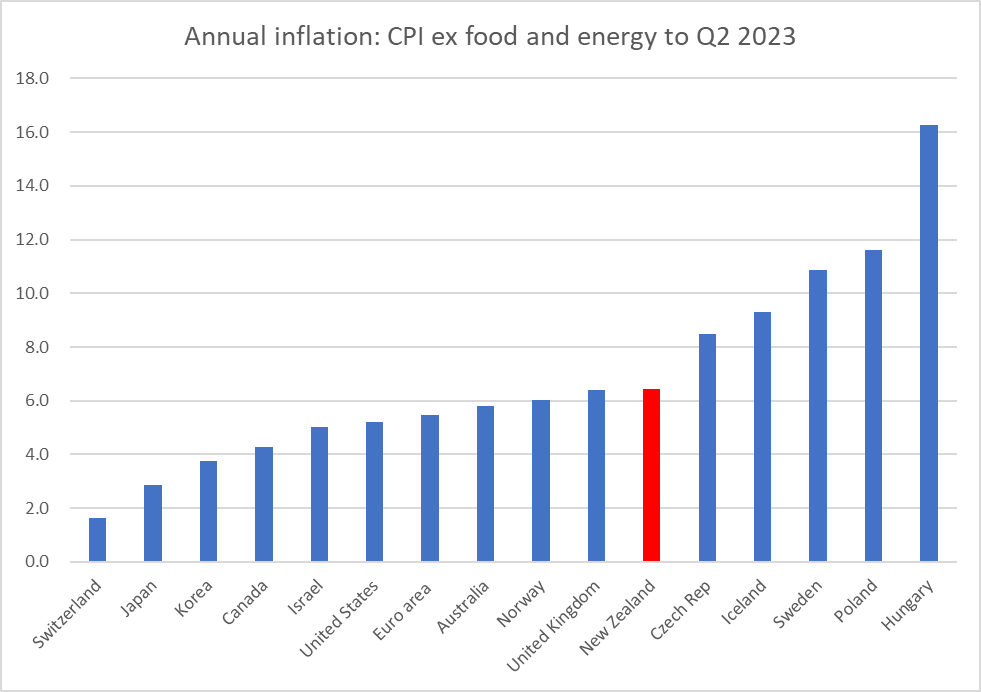

The central banks in Australia, Canada, and Norway have faced big increases in the respective national terms of trade (export prices relative to import prices) over the last 3+ years. All else equal, a rising terms of trade – especially when, as in each of these cases, led by rising export prices – tends to increase domestic incomes and domestic consumption and investment spending and inflation. It isn’t mechanical or one for one (in Norway, for example, they have the oil fund into which state oil and gas revenues are sterilised) but the direction is clear: a rising terms of trade is a “good thing” and more spending, and pressure on real resources, will typically follow in its wake.

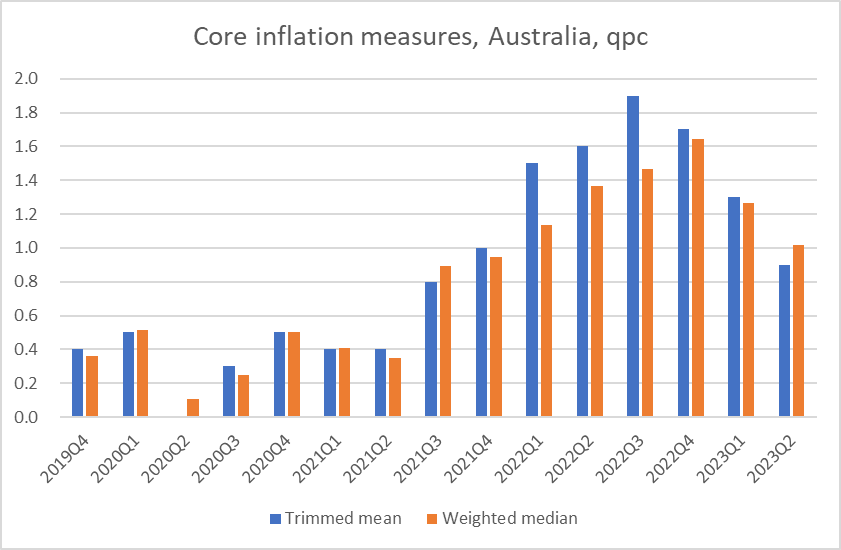

Here is the contrast between New Zealand and Australia over recent years.

In Australia a 25 per cent lift in the terms of trade is roughly equal to a 5 per cent lift in real purchasing power (over and above what is captured in real GDP). A 10 per cent fall here would be a roughly equivalent to a 2.5 per cent drop in real purchasing power. As it happens, over the last couple of years (since the tightening phases began) the terms of trade have been weaker than the Reserve Bank expected, all else equal a moderate deflationary surprise.

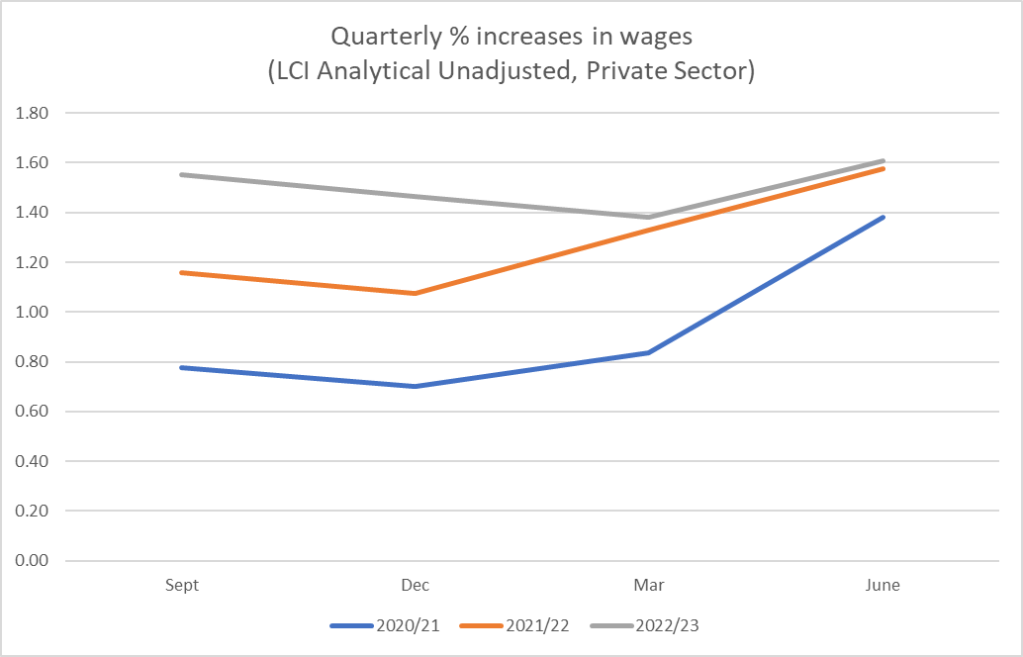

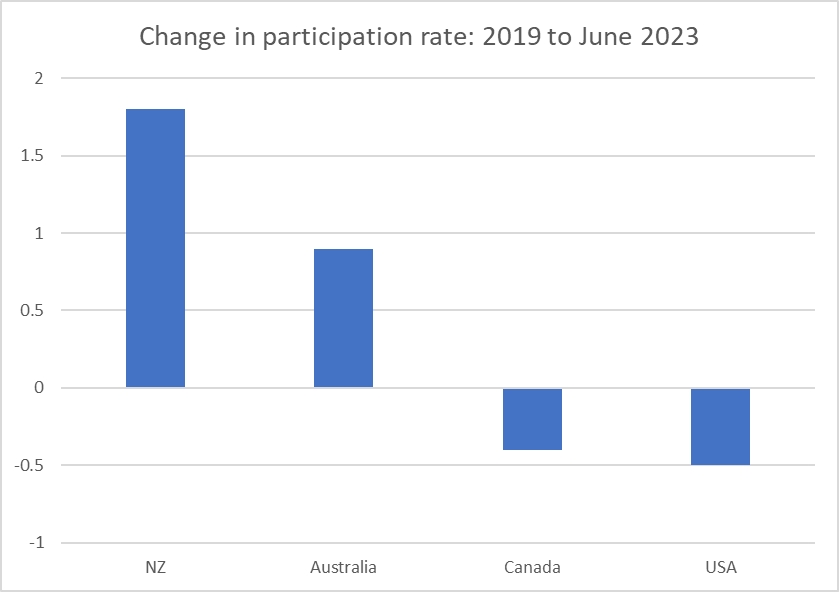

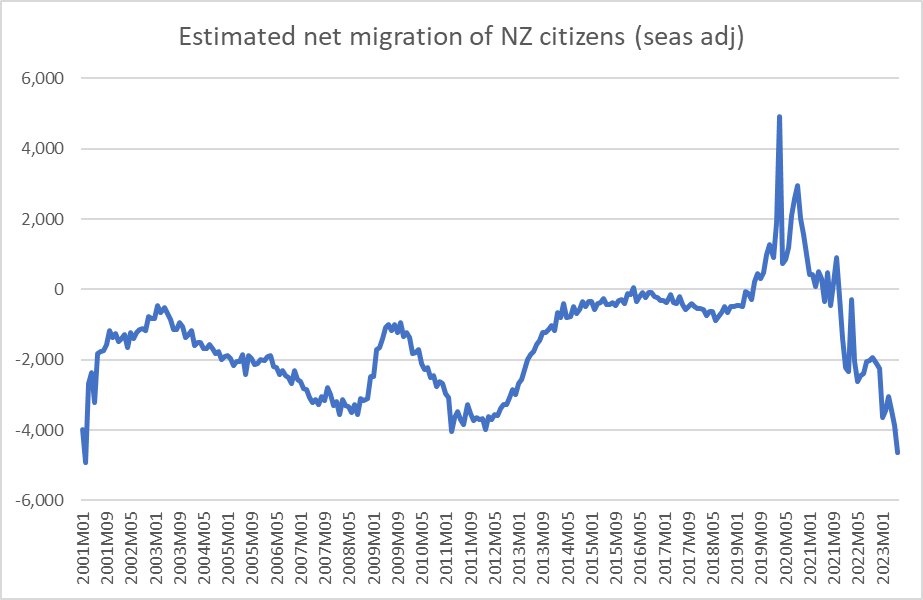

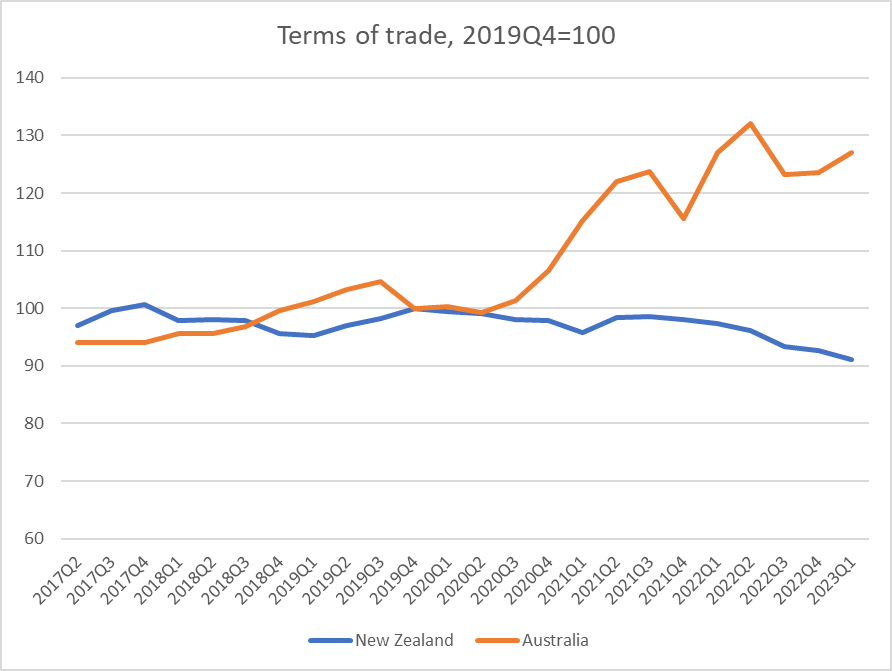

But the other big deflationary influence was the closed borders. I’m not here getting into debates about the merits of otherwise of such policies. Central banks simply have to take whatever else governments (and the private sector) do as given and adjust monetary policy accordingly to keep (core) inflation near target. The fact was that our borders were largely closed to human traffic for a long time, New Zealand has more exports of such services (tourism and export education) than imports, and exports of services are far from having fully recovered pre-Covid levels.

We don’t have easily comparable tourism and export education data across countries, but we can look at how exports of services changed as a share of GDP. From just prior to Covid to the trough, New Zealand exports of services fell by 5.7 percentage points of GDP, a shock exceeded only by Iceland (-12.7 percentage points) – the fall for Australia was just under half New Zealand’s, and for most advanced economies (of the sample in the chart above) the fall was 1-2 percentage points of GDP. In most countries, that trough was in mid 2020, while in New Zealand it was not until early 2022.

Some ground has been recovered (most starkly in Iceland) but New Zealand (and to a lesser extent Australia) are still living with a material deflationary shock from this side of the economy. Real services exports in 2023Q1 were 26 per cent (seasonally adjusted) lower than in 2019Q4, just prior to Covid.

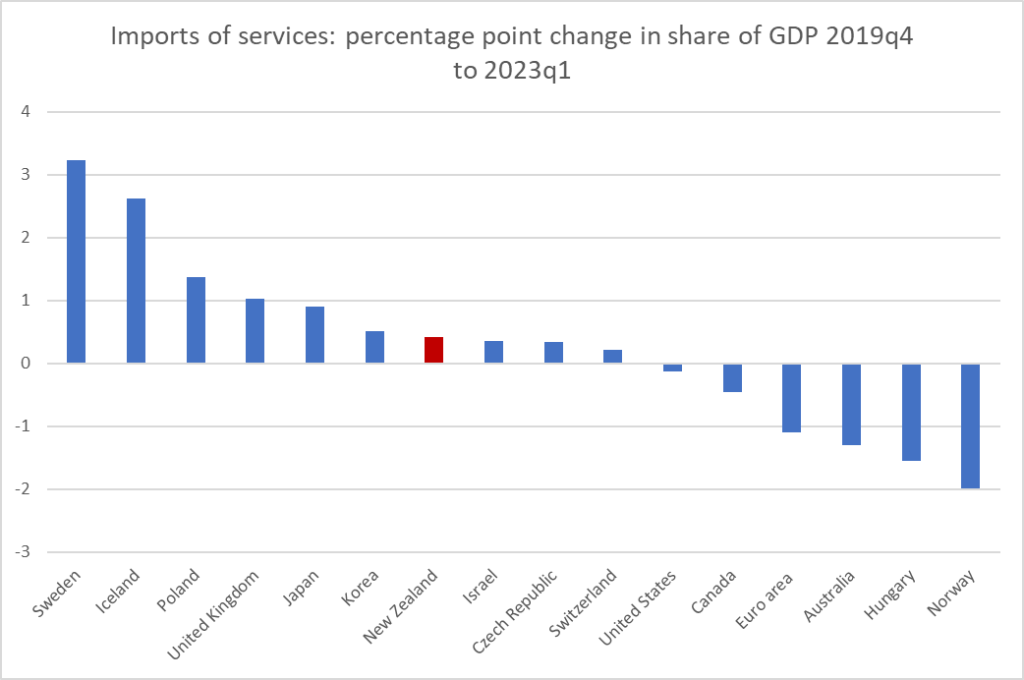

Now, again you will note that this isn’t the entire story. After all, New Zealanders couldn’t travel abroad easily for much of the time either, and money they would have spent abroad seemed to be substantially diverted to spending at home (probably more so than was initially expected). That reduction of imports of services was large (3 percentage points of GDP, with Australia 4th largest of this advanced country grouping) but early – the trough for New Zealand as for most of these advanced countries was as early as 2020Q3.

But that was then. This chart shows the change in imports of services as a share of GDP from just pre-Covid to our most recent data (2023Q1). That share has fully recovered here, with an increase very similar to that of the median country.

So, relative to pre-Covid (and pre-inflation surge), imports of services as a share of GDP are about where they were, and exports of services were still materially lower as at the last official data.

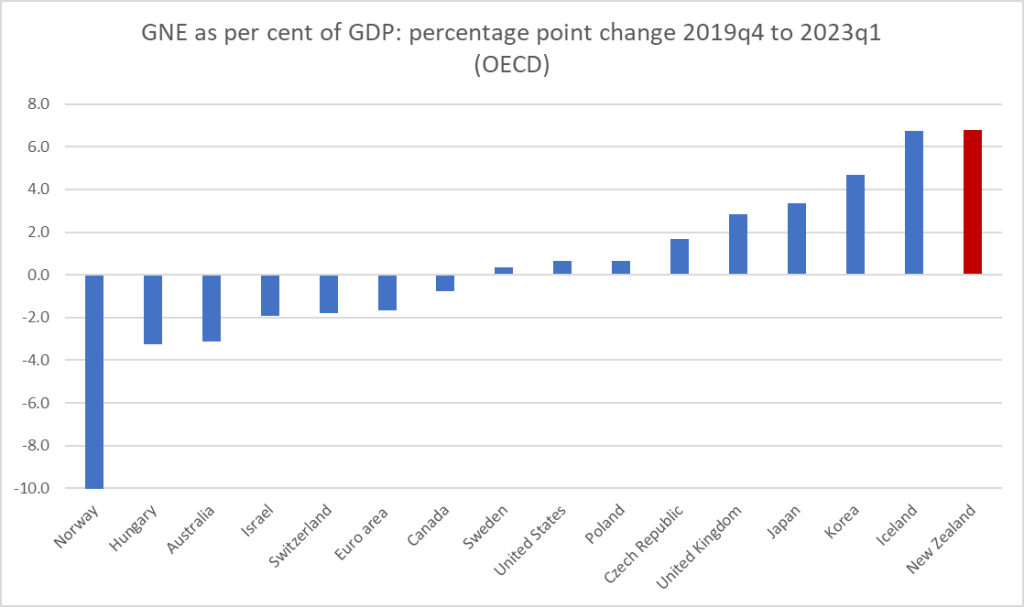

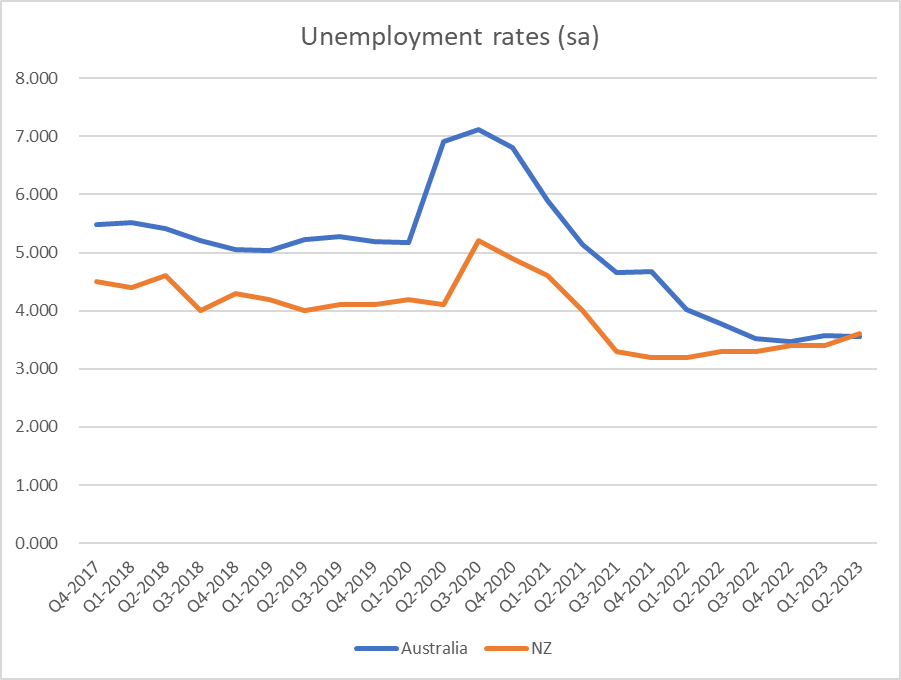

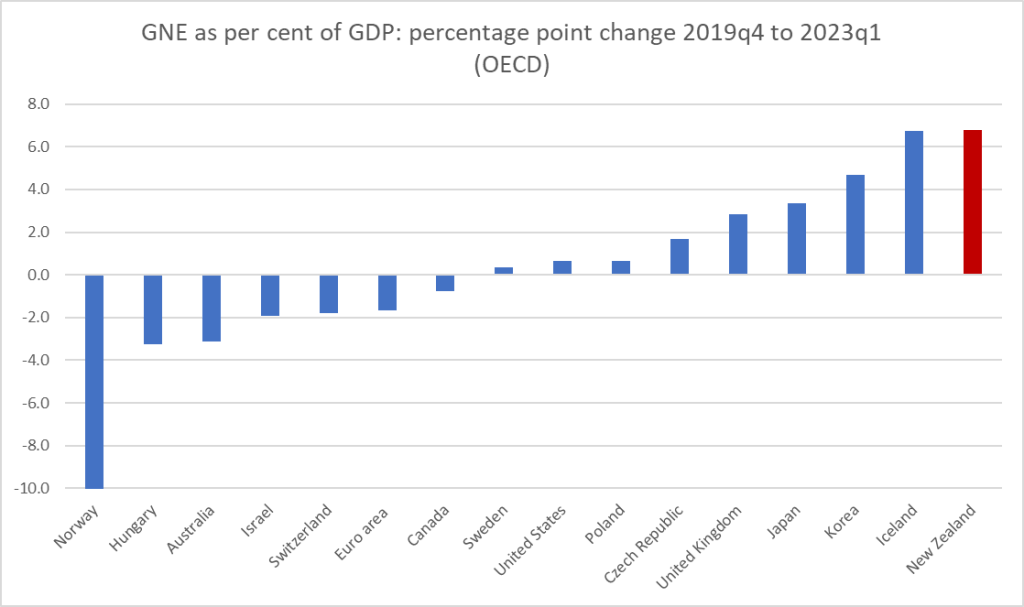

With a deflationary shock like this you might have reasonably thought that the Reserve Bank, if it was to keep inflation near target, would need to induce or ensure faster growth in domestic demand (than some other countries). Yesterday I showed this chart (remember, GNE is national accounts speak for domestic demand). New Zealand was at the far right side of the chart (strongest growth in domestic demand as a share of GDP).

But what if we treated the change in the services exports share of GDP as an exogenous shock that, all else equal, the central bank legitimately had to respond to? In this version of the chart I’ve subtracted the reduction in services exports as a share of GDP.

It makes a material difference to the New Zealand numbers, but even so we are still left with an increase in the share of GDP that is third highest on the chart, about the same as the UK which (as is well known) is really struggling with inflation. (In case you are wondering Korea has relatively modest core inflation now – so first chart – but still about 3.5 percentage points higher than it was just prior to Covid; for us the increase has been about 4 percentage points.)

There are lots of numbers and concepts in this post and it isn’t always easy to keep them straight. But the key points are probably:

- echoing yesterday’s post, don’t be distracted by the Governor’s spin about Russia or the weather or whatever (they just don’t explain core inflation to any material extent) or spin (probably more from the Minister) that every advanced country is in the same boat (they aren’t, see first chart),

- more than other advanced countries, we should have been predisposed to being able to have kept inflation in check a bit more easily, having had both a fall in the terms of trade (very much unlike Australia and Canada) and a sustained fall in exports of services that as a share of GDP is materially larger than any other advanced economy has seen. To be clear, those are bad things, making us poorer, but all else equal they were disinflationary forces,

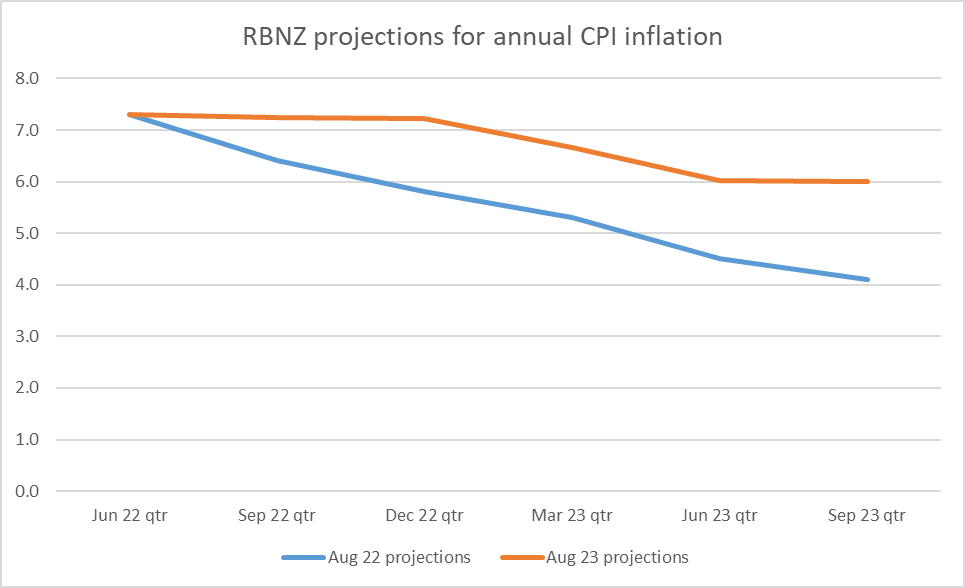

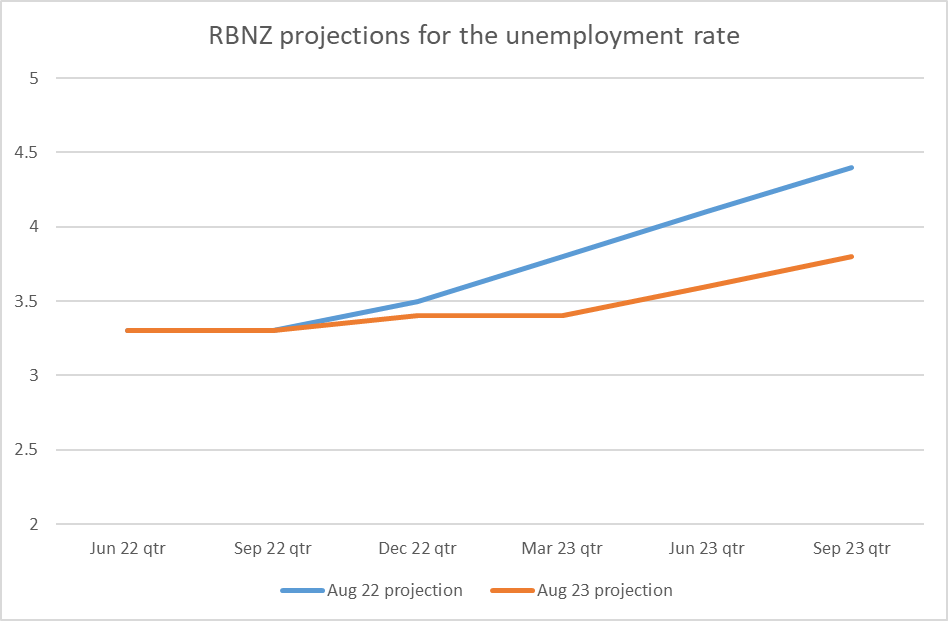

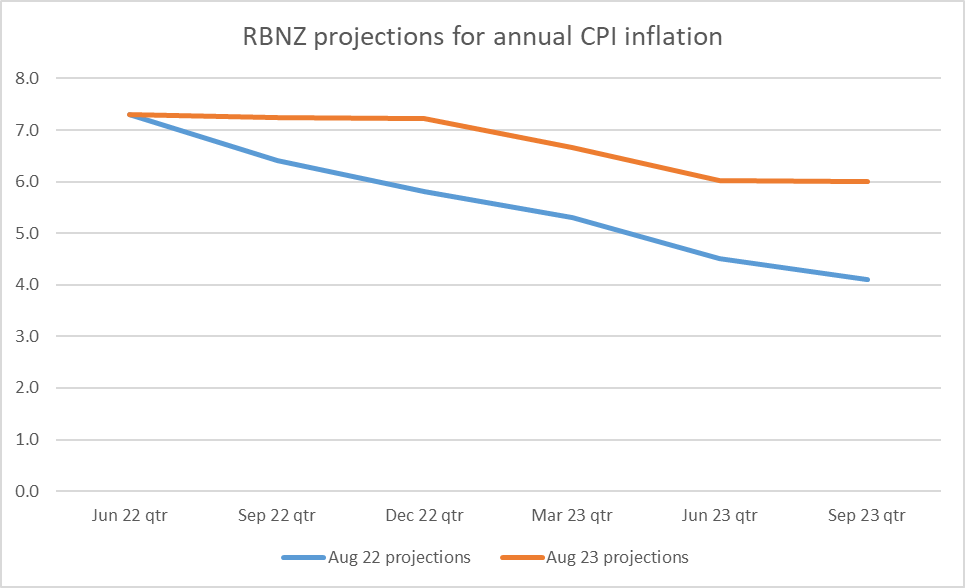

- and yet, core inflation here is in the upper half of the group of advanced economies and (as the MPS acknowledged) is not yet really showing signs of having fallen (unlike some other advanced countries, notably Australia, the US, and Canada),

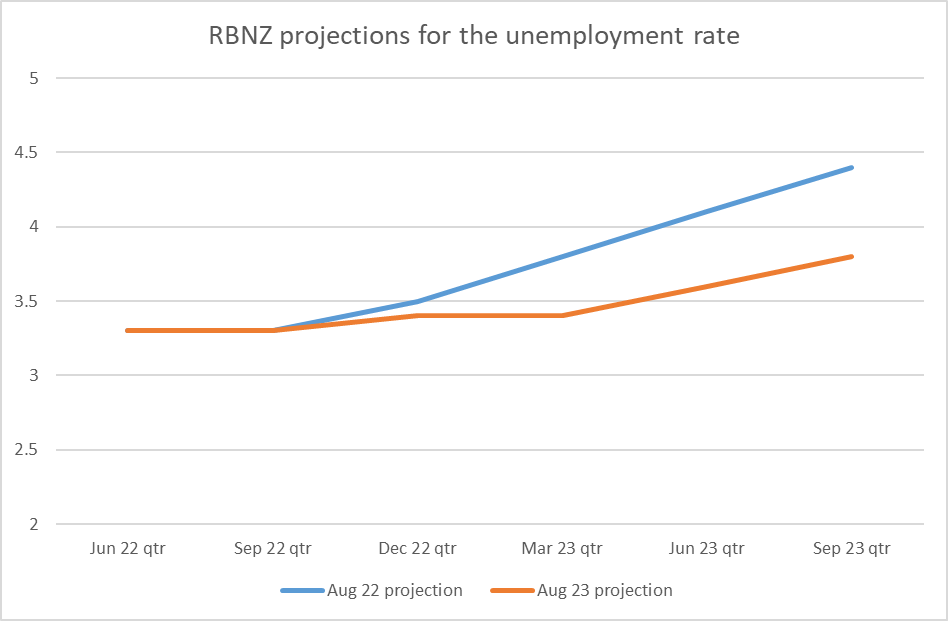

- the difference is about Reserve Bank choices and forecasting errors. The Reserve Bank can’t control the terms of trade or exports of services, but its tool – the OCR – is primarily about influencing domestic demand. They ended up producing some of the strongest growth in domestic demand (absolutely or relative to nominal GDP) anywhere in the advanced world. It wasn’t intentional, but it was their job, and their mistake resulted in high core inflation.

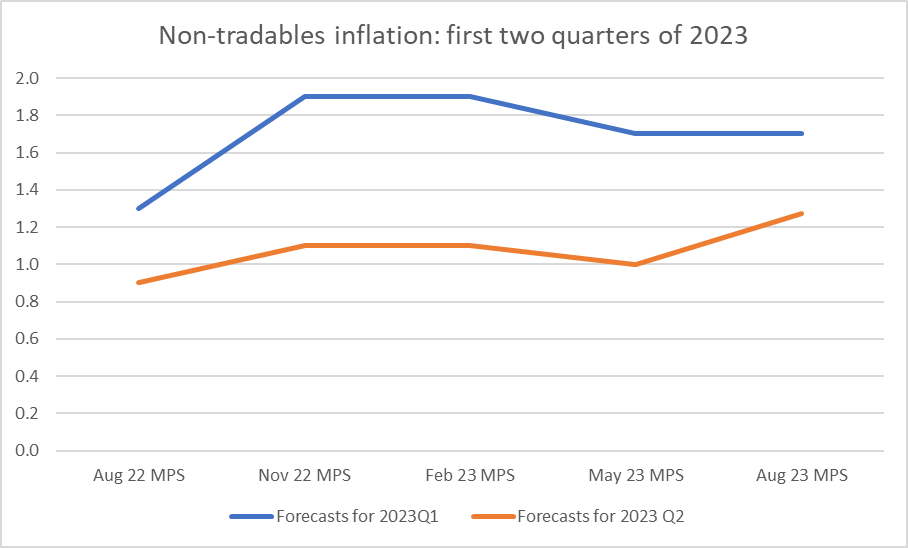

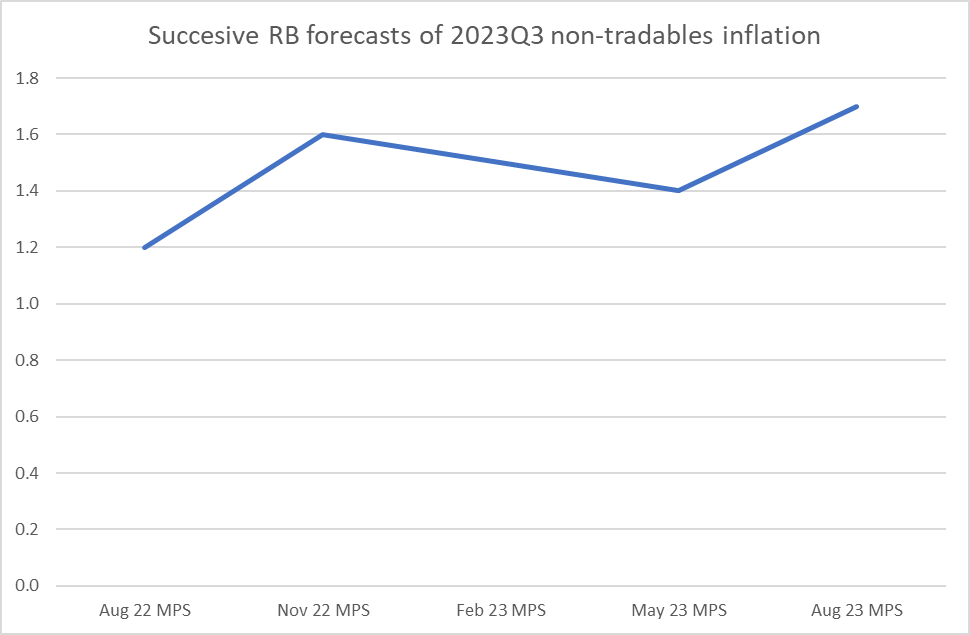

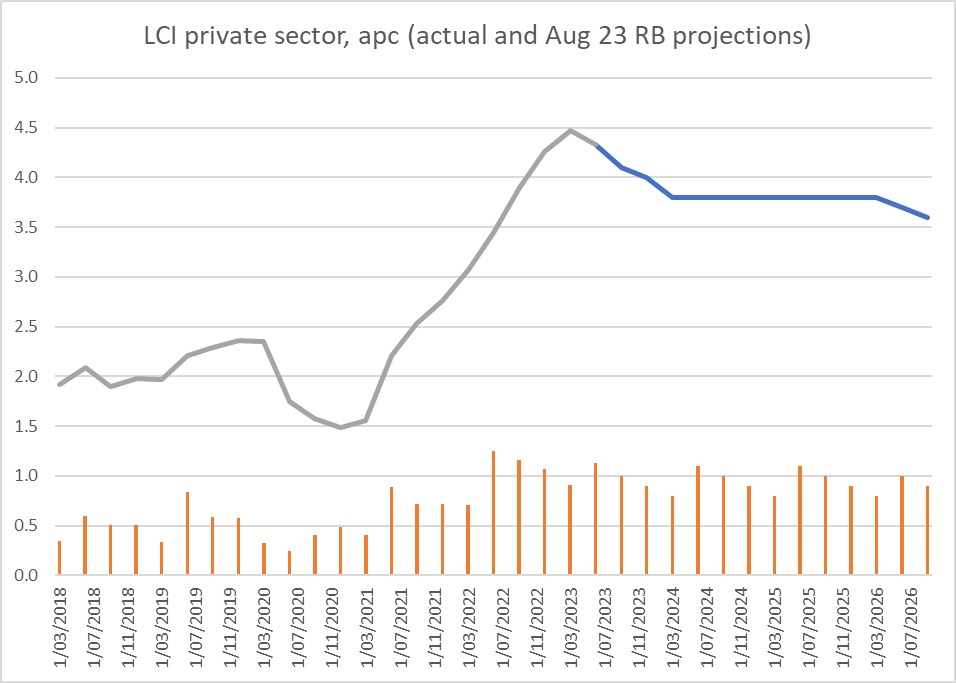

The Reserve Bank doesn’t publish forecasts of nominal GNE – and note that my charts have shown a big increase in GNE relative to GDP – but even their nominal GDP forecasts, even just starting from two years ago when they first thought it was time to start tightening, have materially understated domestic demand growth

and over this period they have actually over forecast real GDP growth.

Again, I’m going to end on a slightly emollient note. Macroeconomic forecasting is hard, and especially in times as unsettled as these. I heard an RB senior person the other day noting (fairly) that they couldn’t tell when the borders would fully reopen, or how quickly people flows would respond when they did. Personally, I’m less inclined to criticise them for getting their forecasts wrong (“let him who is without sin cast the first stone”) than for the sheer lack of honesty and straightforwardness, and the absence of either contrition (in respect of failures in a job they individually chose to accept – no one is compelled to be an MPC member) or hard critical comparative analysis. But…..relative to other countries they had advantages which should have given us a better chance of keeping inflation near target, and things ended up as bad or worse as in the median advanced country.

If forced to confront these arguments the Governor would no doubt burble on about “least regrets”. But the least regrets rhetoric a couple of years ago was really about – and they know this – the risk that inflation might, if things went a bit haywire, end up at 2.5 per cent or so for a year or two, rather than settling immediately around the target midpoint of 2 per cent. It wasn’t – was never even suggested as being – about the risk of two or three years of 6 per cent core inflation, and a wrenching adjustment to get it back under control.

They may still claim to have no regrets. They should have many. We certainly should. They took the job, did it poorly, and now won’t even openly accept (what they know internally) that it wasn’t the evil Russian or a cyclone or….or….or…it was them, Orr and the MPC. They made mistakes (they happen in life), with no apparent consequences for them, and not even the decency to front up, acknowledge the errors, and say sorry.