In a post a couple of weeks ago I outlined some reasons for scepticism about the case for increasing the OCR by 50 basis points specifically at the then-forthcoming OCR review. My point was mostly about the data hiatus – the OCR decision would be taking place almost 3 months after the most recent CPI data and more than 2 months since the last main labour market data. It seemed (and seems) foolish for the MPC to stick to its schedule of review dates, including the long summer holiday it will give itself after next month’s MPS. It remains highly problematic that New Zealand governments have penny-pinched on core statistics and as a result we have such slow and infrequent macro data (we got the September quarter CPI inflation data yesterday, Switzerland by contrast released September month data on 3 October).

But there were also some considerations in the macroeconomics

- the reasonably long lags in monetary policy (the OCR really only having been aggressively tightened fairly recently)

- weakening commodity prices,

- relatively subdued nominal GDP growth, among the very lowest in the OECD,

- and some indications in core inflation measures that at least things had not been getting worse (continuing to spiral upwards)

All the inflation rates were, of course, unacceptably high.

Of course, as was universally expected the MPC did raise the OCR by 50 basis points in their October review. And yesterday we got the September quarter CPI data, which took by surprise all those who’d published forecasts (and, I guess, almost any of us who’d heard their headline forecasts). The outcome was higher than the Reserve Bank’s last published forecast, but since that forecast was more than two months old and anyway isn’t broken down into headline and core components – and they’d given us no sense of an update in the October review – not too much weight should now be put on that particular aspect of the surprise.

I don’t do short-term components forecasting, so what follows isn’t about the extent of the surprise (immediate prior expectations vs outcomes) but about what to make of the actual outcomes and current inflation. First, I’ll step through and update the charts from the earlier post.

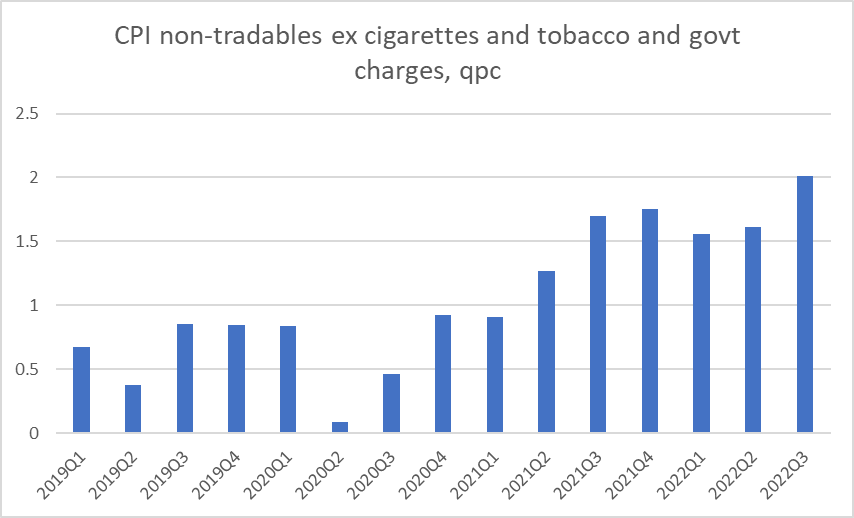

These two – commonly used abroad – core inflation measures might suggest a little room for encouragement. Both quarterly changes are still high (far too high), and the gap between them is unprecedented, but they both look as though they could be past their respective peaks.

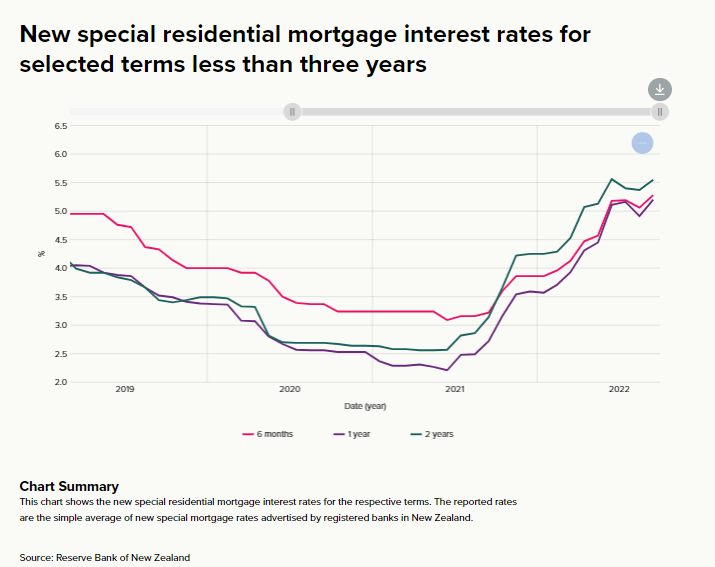

Monetary policy always takes time to work, and as this Reserve Bank chart reminds us it was only late last year that new mortgage rates really started rising.

But then there are these two exclusion measures

neither of which offers any reassurance.

And the picture here is similar

and from these monthly food price components, a bit of a mixed bag, but at least nowhere near as bad now as a few months ago.

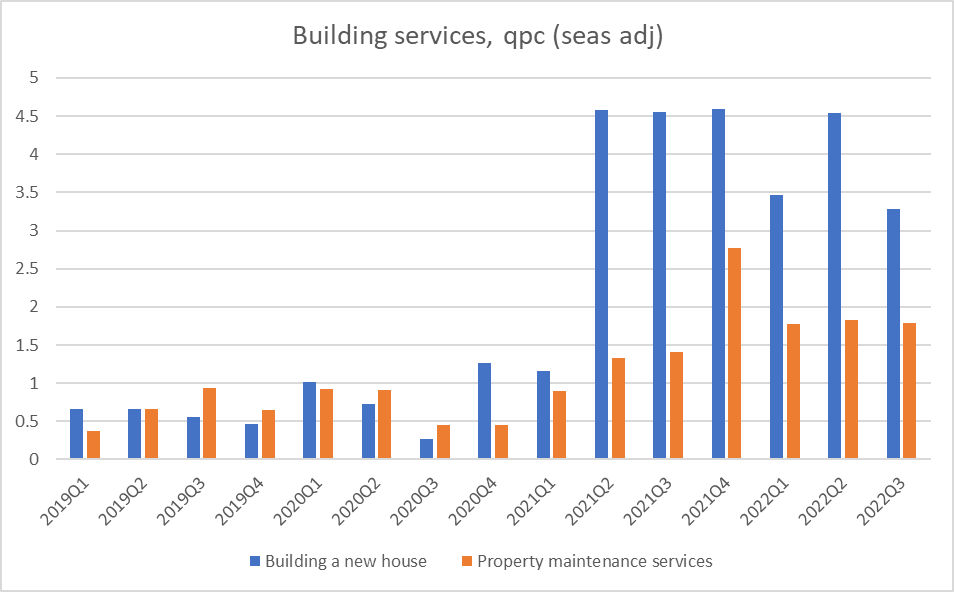

The building market has been one of “hottest” areas of the economy and the labour market, with staggering rates of increases

Those numbers are still high but seem to be beginning to move in the right direction.

And then there are rents. Rents now make up just over 10 per cent of the CPI. On a quarterly basis the rents item in the CPI increased by 1.2 per cent in the September quarter, as high (equally high) as it has been this cycle. On an annual basis, this is the picture

In the CPI rents are included using a stock measure – the rate of increase in the average rents being paid by all tenants. And there is a certain logic to that, but we also know that new rents are falling (not just the growth rate slowing, but the level of rents dropping)

The flow measure – new rents – is (naturally) noisier but it (also naturally) leads the stock measure. There is a lag from monetary policy to the CPI for numerous reasons, but one is the choice to include average prices rather than marginal prices for rents. New rents – the ones policy and market developments affect most immediately – have now been falling for several months.

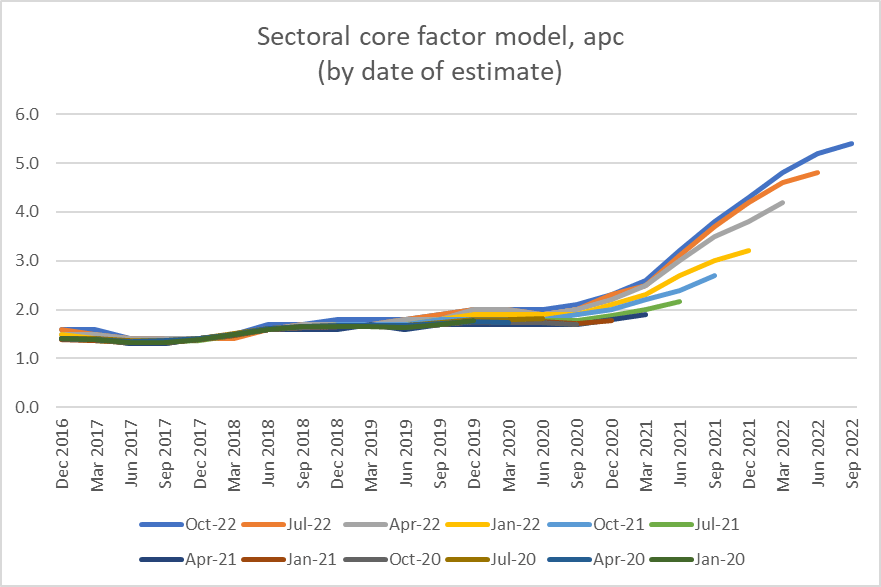

For completeness, I’m including this chart of the Reserve Bank’s sectoral factor model measure of core inflation.

It used to be the Reserve Bank’s preferred measure (and mine too – I championed it when I was still at the Bank), and it is probably still the single best guide to historical core inflation, but (in the nature of the technique) it is prone to big and lagging revisions when inflation is moving a lot. When the September 2021 CPI came out last October the model estimated core inflation then to have been 2.7 per cent (high, but still inside the target range), but the model – learning from what has happened since – now reckons core inflation last September was already up to 3.8 per cent. At this point, there really isn’t any information (good or ill) in the latest quarterly observations (which in any case use annual rather than quarterly data).

Moving beyond the specific inflation data series, there are a few other considerations that seem relevant to me. The first is to remember the lags (something notably absent from any of the media coverage I heard or read). There are at least two that are relevant. First, the September quarter CPI is really a mid-August measure: there are some noisy components – notably petrol – sampled weekly, and food is captured monthly but the whole thing is centred on 15 August, which is now a bit more than two months ago. So we (and the RB) aren’t exactly using real-time data. And second, the OCR takes time to work – this isn’t in dispute and shows up in all the modelling work – and on 15 August the OCR was 2.5 per cent (it was raised at the MPS a couple of days later). In fact – and it is easy to forget this now – until 12 April, the OCR was no higher than 1 per cent, the level (designed to be somewhat stimulatory) it had been at immediately prior to Covid. Now, of course markets and market pricing anticipated OCR increases to come to some extent, but the market (let alone firms and households) have been repeatedly surprised, constantly revising up their view of what OCR would be required.

I’m also not about to take a view on what the Reserve Bank could or should do in November. Market economists have to, I don’t. There is another round of really important labour market data due out in a couple of weeks (of which the most important bits should be the employment and unemployment numbers rather than wages). Of course, it lags too – centred on mid-August (and I really don’t understand why a household survey collected by phone within a quarter can’t be processed much more quickly than SNZ manages) – but it will still represent an addition to our knowledge. If, for example, the unemployment rate were to have dropped further, the argument for a big OCR increase would inevitably strengthen, all else equal – people will cut central banks less slack now than they might have if we were dealing with core inflation at, say, 3.5 per cent.

But is always going to tempting to just ignore the lags, even after increases in the OCR of unprecedented pace this year. And the lags are real, the lags matter. Robert MacCulloch, macroeconomics professor at Auckland, yesterday reminded us of Milton Friedman’s take on that issue almost 55 years ago.

There was a time for 75 or even perhaps 100 basis point OCR increases – last November or February perhaps – but for now it is much less clear that now is one of those times (and few if any of those now calling for such large increases now were calling for them then).

Of course, it doesn’t help that the MPC chooses to take a long summer holiday. That really should be revisited now.

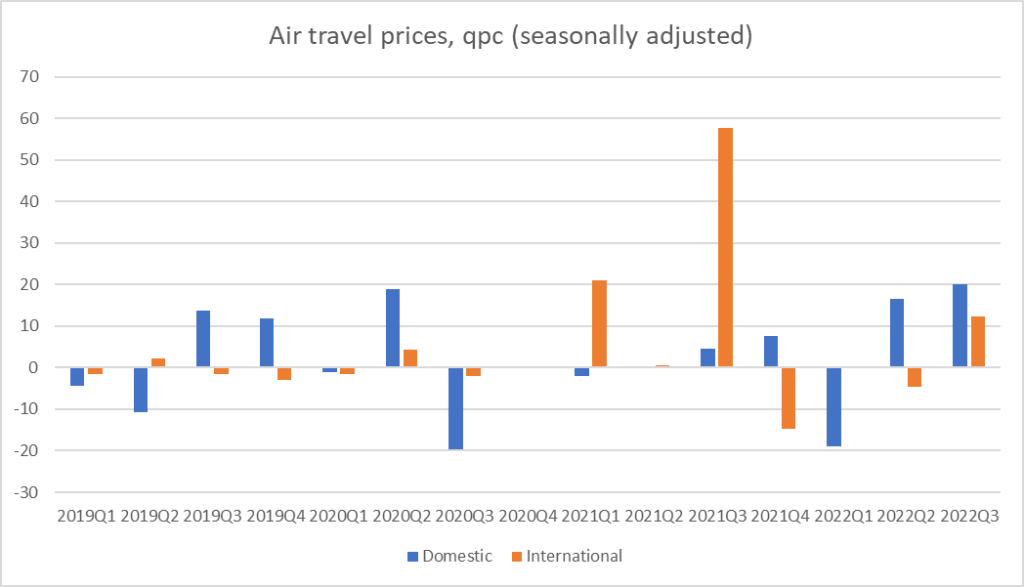

And just one last graph, since air travel prices were a non-trivial influence in yesterday’s headline (and exclusion) measures. More than a little noise in those series.

A worrying aspect is the trend which in terms of currency, commodity prices strongly indicates the market view of NZ and probably reflects that trends started changing direction in late 2017 and have got increasingly worse.Peoples perception is a driver of their actions and also has a lag to implementation and the honesty and accuracy of political/RBNZ statements a key factor – and one which seems to be very negatively viewed. A perfect economic storm is on the horizon and NZ will get wet at best.

LikeLike

The RBNZ has pushed interest rates too far and too fast as it is already. The NZD is falling which increases inflation. Higher interest rates act to prop up a falling NZD as the yield improves, speculators prop up the currency by buying NZD. The trade off is a declining NZ economy that speculators would put downwards pressure on the NZD. If the NZD falls then inflation rises. If higher interest rates cause the NZD to fall then clearly the RBNZ has raised interest rates too far.

Clearly increasing interest rates further would be detrimental to the NZ economy which forces up inflation. But I have realised the RBNZ does not know how to balance the scale ie no knowledge of how the real world works nor how to read a set of financial statements.

Also interest rates are a cost to business which would respond by increasing sale prices to maintain margins. With China production and delivery to market still compromised by a covid elimination strategy and shipping costs still disrupted and rising, interest rate increases will just be passed onto consumers and consumers have no cheaper alternatives. In effect by raising interest rates, the RBNZ is adding upward pressure on inflation. Dumb and getting dumber, Adrian Orr and his RBNZ team of merry clowns.

LikeLike

While policy over-reaction is a risk, don’t forget the subtle counter-revolution against monetary policy that has taken place in NZ over the past 25 years. Coming out of the disinflation era of the late 1980s, a pervasive view developed that the RB had been unnecessarily brutal with monetary policy and was just too zealous in pursuing price stability. Contributory factors included the view that the costs of disinflation on ordinary NZers had been unnnecessarily high, concerns about the exchange rate, which seemed perenially overvalued, and an irrational belief that monetary policy was somehow always holding back the economy – the Reserve Bank was to blame for everything. This view gained serious ascendancy with the Treasury.

It was a ‘view’ that certainly resonated politically and, as you know, a number of political parties campaigned on their being a ‘better way’ to operate monetary policy (although none of the models offered withstood serious scrutiny). Labour’s ‘better way’ was the introduction of the maximum sustainable employment clause, a circuit breaker designed to ensure that the Reserve Bank never pushes the inflation agenda too hard. Board, MPC and governor selection has no doubt favoured more ‘sympathetic’ types that the government knows are less likely to ‘overreact’ in the manner Professor McCulloch describes. Your commentary last week about the Board turning a blind eye to the recent inflation record would be an exemplar of the softer world the RB now operates in (cf 1989).

Bottom line: there is, in my view, at least as much risk that monetary policy remains inadequately tight to do the job.

LikeLike

Part of the answer appears to be getting more recent figures. If Switzerland can get the previous month’s stats within a few days why can’t RBNZ?

LikeLike

Ah well, indeed. Government spending priorities is the almost-entire answer (spending on econ stats has typically and for decades been too low). There is a slightly more substantive issue in the construction costs in our CPI are done based on surveys of builders as what they would quote to build a house of standard specifications. Even if most other prices could be gathered, manually or electronically, in near real time, that one probably couldn’t be (given the typical small scale of most NZ building firms). Still doesn’t excuse a 2 month from the midpoint of the survey quarter.

LikeLike

Please note that I adopted my nom de guerre before I started reading this excellent blog.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Utopia, you are standing in it!.

LikeLike

I can’t help but think where oil goes – we go (on the subject of inflation)… Biden gets this too;

https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2022/10/18/biden-oil-supplies-emergency-reserves/10535994002/

As our RB/Govt can do nothing but sit back and accept that, I think the mortgage pain with retail rates where they are now, suggests it’s time to take the foot off the accelerator (no more OCR increases this side of Xmas). We need to wait and see how those coming off 2- year fixes weather the storm.

Rents are heading in the right direction; house prices (aside from new builds) are heading in the right direction – whereas, food prices are a reflection of oil prices, and middle NZ will just end up adjusting diets to cope (i.e., Weetbix vs Nutrigrain). The Govt will have to spend a lot more on emergency assistance to avert the crisis of our most vulnerable (and included in those will be a new cohort coming off a sub-3 interest rate to a plus-6 one).

LikeLike

Michael, I am just working my way through my spreadsheet and it is clear that much of the forecast error from the RBNZ and the Street is due to compositional changes in the weighting of the CPI. These compositional changes bring the CPI index for June 2022 back into line with similar weightings pre-COVID and should be thought of as a pandemic-related disturbance.

Two examples stand out; domestic and international accommodation and domestic and international airfares. The accommodation weighting increased from 0.89% to 1.55% while the airfare weighting increased from 0.73% to 2.01%. The former increased in price 6.3%q/q (with domestic accommodation prices surging 11%q/q) adding 0.06pp while the latter increased 20%q/q, adding 0.25pp to the CPI. At a guess, I’d say compositional changes in the CPI will have added around 0.3-0.4pp to the forecast error and this largely reflects the re-opening of the economy (i.e. price level effects) and weightings changes.

Elsewhere, things looked pretty much BAU; housing rose 2.3%q/q against my expectations of 2.2%q/q and as you point out, the dynamics in housing are softening, as are housing-related services such as real estate agents’ fees.

With the weightings issue now largely ironed-out, my projections suggest that inflationary pressures will clearly abate from here. Problem is, from the RBNZ’s perspective, that’s a very difficult conversation, much easier to simply hike 75bp in line with the OIS, raise forward guidance, and when the economy tanks, which it’s in the process of doing, say “well who could have foreseen that?”

LikeLike

Reckon inflation will drop hard over coming year. I just can’t grasp the risk of “self fulfilling” dynamics or “second round effects” when the price or money is ratcheting higher meaning money will be destroyed over the coming 12 months (especially in NZ given bank debt). You need more money in the system for a higher and higher price level…….as per Milton…I think…

LikeLike