The Herald’s economics columnist Brian Fallow devoted his column last Friday to the Reserve Bank’s proposal to massively increase the proportion of their balance sheets banks would have to fund by equity. He ended on what seemed to be a moderately sceptical note.

So we are left trying to weigh a highly debatable but significant cost against an incalculable benefit.

As I’ve noted here, the sort of cost-benefit calculus we can glean from various Reserve Bank publications just doesn’t stack up at all. In his speech the other day (which a couple of readers have suggested I was too generous towards), the Deputy Governor indicated that the level of GDP might be up to 0.3 per cent lower (permanently) as a result of these changes. Call it an annual insurance premium of 0.25 per cent of GDP (and bear in mind that the estimates Bascand is using don’t take account of the implications of most of our banks being foreign-owned, which raises the cost to New Zealand).

If we knew with certainty that:

(a) adopting these much higher capital ratios would prevent a crisis in 75 years time that would have otherwise cost 40 per cent of GDP (recall that the proposals aren’t supposed to prevent 1 in 200 year crises, but are presumably supposed to prevent 1 in 150 years crises, and 75 years is halfway through 150 years – the crisis could happen next year, or in year 149), and

(b) that the new higher capital ratios would be applied consistently for the next 75 years

that might be a borderline reasonable bet – the benefits might roughly match the costs.

If you thought instead there was no more than a 50 per cent chance that the new policy would be applied consistently for 75 years (and given how politics, personalities, and conventional policy wisdom has changed quite a bit, to and fro, since 1944 that seems generous) , you’d need to be preventing a crises twice as large for the insurance policy to be worthwhile.

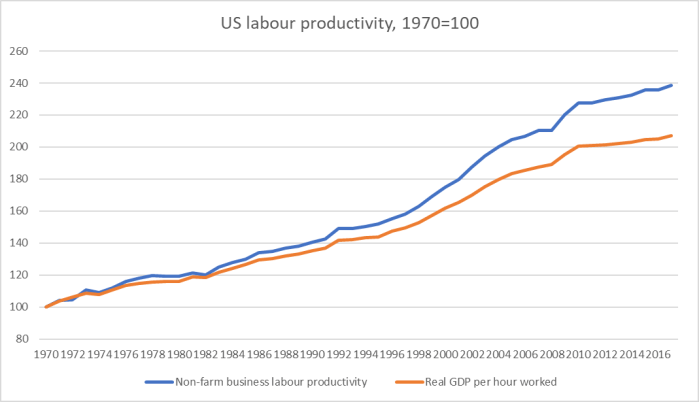

As a benchmark for how serious these events can be, you could think about the United States since 2008. Over 2008/09, the United States experienced the most severe banking crisis of (at least) the modern era, since (say) the creation of the Federal Reserve. (The Great Depression itself was, of course, worse, but it was mostly a failure of monetary policy management and institutional design rather than a banking crisis).

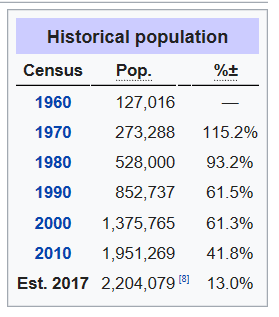

I’ve shown this chart previously. Real GDP per capita for the US and New Zealand from 2007q4.

The United States was the epicentre of the systemic banking and financial crisis. New Zealand did not experience a systemic banking crisis at all. At least on the OECD’s estimates, the output gaps of the two countries were pretty similar in 2007. And there is no just credible way you can come up with estimates that have the United States doing (cumulatively, in present value terms) 40 per cent of GDP worse than New Zealand. Do the comparisons of the US with other OECD countries that didn’t run into serious banking problems – eg Australia, Canada, Norway, Israel, Japan – and you still won’t find cumulative output losses sufficient to justify the sort of tax the Reserve Bank of New Zealand wants to lump on our economy.

In fact, for what it is worth, here is the cumulative labour productivity (real GDP per hour worked) growth of the United States and those non-crisis countries for the period 2007 to 2017 (from the OECD databases).

| United States |

10.6 |

|

|

| Australia |

14.0 |

| Canada |

9.6 |

| Israel |

10.1 |

| Japan |

8.3 |

| Norway |

3.0 |

| New Zealand |

4.4 |

Sure, there are all sorts of other things going on in each of these countries. But bad as the 2008/09 banking crisis was in the United States, it is all but impossible to come up cumulative cost estimates that would reach even 20 per cent of GDP (crisis country experience over the experience of non-crisis countries).

And if the Reserve Bank continues to believe otherwise, the onus should be on them to make the case, to set out their arguments, assumptions, and evidence.

(Note, that none of this is to suggest that the 2008/09 recessions were anything other than undesirable and costly. Recessions generally are. But there are lots of low probability bad things in our world, and not all of them are worth paying the price to try to prevent.)

But even having come this far, I’ve risked conceding too much to the Reserve Bank ‘s story. In part, that is because the storytelling implicitly treats higher capital ratios as sufficient to spare an economy all the costs associated with a banking and financial crisis. And in part (but not unrelated to the previous point) because it tends to treat systemic banking crises as bolts from the blue – unlucky bad draws imposed on a country when the Lotto balls are selected. Neither is true.

Unfortunately, Brian Fallow seemed to buy into some of this sort of implicit reasoning in his column.

But in a complicated and perilous world it is idle to suggest that stress tests or banks’ internal modelling can accurately quantify the probability and magnitude of a major economic shock that could threaten the solvency of banks. Or even forecast the nature of the shock: another global financial crisis, perhaps?

The last one inflicted the deepest recession New Zealand had suffered since the 1970s.

A pandemic against which we are pharmacologically defenceless? It’s 100 years since the Spanish flu killed more people than WWI.

International hostilities breaking out in some surreptitiously weaponised but systemically vital realm of cyberspace?

Or a more conventional geopolitical conflict? The current crop of world leaders do not inspire confidence.

One might note first that the stress tests the Reserve Bank requires banks to undertake have deliberately used highly adverse combinations of shocks (rising unemployment, falls in house prices etc). They are deliberately designed to look at really adverse events.

One might also note that – contrary to the implication here and in Geoff Bascand’s speech – the banking crisis (failure of DFC, need to recapitalise BNZ) did not “inflict the deepest recession New Zealand has suffered since the 1970s”, rather it was one (probably rather modest) factor in a range of contributors (disinflation, structural reform, fiscal adjustment, downturns in other countries etc).

But what I really wanted to focus on were the final three paragraphs in that extract, which imply that banking crises arise out of the blue. And they just don’t. They never (or almost never) have. Might they in future? Well, I suppose anything is possible, but we can’t sensibly take precautions against everything.

The prospect of a serious pandemic is pretty frightening. But awful as the episode 100 years ago was, it didn’t result in systemic banking crises. Cyber-warfare sounds pretty scary as well, but it isn’t remotely clear how higher bank capital requirements protect us against that. World War Two was dreadful, but it didn’t result in systemic banking crises either. There was a serious financial crisis at the start of World War One, but it was a liquidity crisis not a solvency one, and capital requirements (then, or in some future unexpected outbreak of hostilities) are pretty irrelevant in a crisis of that sort. Do the leaders of the world as individuals or a group command much confidence? Well, no, but then in the last 100 years or so periods when it was otherwise seem rare enough (the PRC and USSR border war of 1969 anyone)? I suppose if we go back far enough a repeat of the Black Death – wiping out a third of the population – wouldn’t be great for the value of bank collateral, but (a) capital proposals aren’t supposed to counter 1 in a 1000 year shocks, and (b) you might think there would be bigger things to worry about then (and a high likelihood of statutory interventions to redistribute gains and losses anyway).

Systemic banking crises – one where banks and borrowers lose lots and lots of money and 5 per cent, 10 per cent or more of bank loans are simply written off in a short space of time – simply do not arise out of the blue, as decent well-managed banks and universally responsible borrowers are suddenly hit by some totally unforeseeable event. Rather they are – always and everywhere – the outcomes of choices made over the years (typically only a handful) previously. Lenders and borrowers make bad – wildly overoptimistic – choices, some just going along for ride, others actively pushing the envelope. In the process, real resources in the economy in question are misallocated, perhaps quite badly, but that cost is something that is really only apparent (only crystallises) when the boom comes to end, whether it ends in a whimper or a bang. Sometimes government policies can play a direct part in helping to generate the mess. In the United States, for example, the heavy state involvement in the housing finance sector greatly exacerbated the imbalances that crystallised in 2008/09. In Ireland, for example, entering the euro and taking on the interest rate fit for Germany and France when Ireland might have been better with New Zealand interest rates, was a big part of the story. Fixed exchange rates have often been a significant factor, both giving rise to initial imbalances, and aggravating the difficult resolution afterwards). Transitions out of periods of heavy regulation can play a role too: in New Zealand (and various other countries) in the late 80s, neither lenders nor borrowers really had much idea of operating in a liberalised financial system. You can go through every modern financial crisis – and probably plenty of the older ones too – and point to the excesses, the over-optimistic lending and borrowing that accumulated in the preceding years. Japan – crisis of the 1990s – was yet another prominent example (Zambia in 1995, a crisis I was quite involved in, was the same).

Would higher required capital ratios have prevented any (many) of these episodes? One can’t answer with certainty. They might have prevented some bank failures themselves, but that isn’t the issue I’m focused on here (which is about the bad lending/borrowing in the first place). Perhaps a few banking systems really went crazy because creditors thought they could offlay all the risks on the state, but that isn’t a compelling story more generally. After all, shareholders still stood to lose everything. A more plausible interpretation (to my mind) of those periods of undisciplined lending/borrowing is that people simply misjudged the opportunities, and got carried away by excess optimism, in ways that meant they just pay much less attention to the potential downsides. The world was different (so people were being told, or they told themselves). If so, most of the misallocations of real resources would happen quite independently of the levels of bank capital requirements that were imposed. And you can mount an argument that high capital requirements may tend to encourage banks to seek out more risks than they would otherwise take, especially in buoyant times, concerned to keep up rates of return on equity. Even if that doesn’t happen, disintermediation would see more risks to be taken on in the shadows – no less resource misallocation in the process, but rather less visibility to the authorities and resolution agencies.

Perhaps good and active bank supervision can prevent those excesses, and misallocations, building up. But that is a (very) different case from one in which ever-more-demanding capital buffers supposedly eliminate (or reduce to minimal levels) the costs when the bad lending crystallises. It isn’t a case the Reserve Bank has made – and they probably wouldn’t, as historically they have been (rightly) fairly sceptical about the value hands-on supervision can add. And it is a case I am pretty sceptical of. And for which there is not much evidence (even allowing for the fact that crises avoided tend to be not very visible). Much as APRA likes to suggest it is an example (in the 2000s) I don’t think they were really tested.

Bank supervisors – and their bosses in particular – breath the same air as everyone else in a society, and when lending and borrowing in a particular country is going badly off course, it is unlikely that the bank supervisory agency will be taking (for long) a very different stance from those around them, and those who appoint them. This isn’t an argument about corruption – although regulators perceived to be realistic and responsive will no doubt attract a better class of well-remunerated job offer – but about political and economic realism. But even if better Irish regulators (say) could really have made a difference in the 2000s, what was really needed were different lending/borrowing practices, not just more capital. More capital wouldn’t have avoided a nasty aftermath (even if it would have reduced some fiscal costs) – and at the peaks of self-confident booms, capital is cheap and easy to raise.

And so we are brought back to the specifics of New Zealand where:

- repeated stress tests conclude that our banking system is resilient to very very nasty shocks,

- the Reserve Bank tells us at every FSR that the financial system is strong and sound,

- we have control of our own monetary policy, including a floating exchange rate (34 years today),

- we have healthy public finances,

- we have little active involvement of the government is directing finance

Against that backdrop, and against the experience in which it is hard to conclude that banking crises themselves (as distinct from the bad lending that later gave rise to them) are worth more than a few percentage points of GDP, in a country not prone to systemic financial crises (the episode doesn’t even meet the test in many collections of crises), with our banks owned mostly from a country also with no track record of frequent serious financial crises, the case just hasn’t been at all convincingly for compelling banks to fund so much more of their balance sheets with equity. Doing so will, on the Reserve Bank’s own telling, involve real economic costs. For benefits that are, at best, tiny and far-distant.

It is disconcerting that in none of the Reserve Bank’s material do they ever show signs of engaging with any of this sort of analysis. Instead, they have a policy preference and prefer assertions and flimsy analysis to any serious engagement with the issues and experience.

My former colleague Geof Mortlock has another piece on interest.co.nz making the case for splitting up the Reserve Bank and creating a separate Prudential Regulatory Agency. I strongly agree with him on that – and have argued the case here last year. Geof is probably more optimistic than I would be about what bank regulators can add, but on this particular item we seem to be as one. Among his long list of what is wrong with the Bank’s conduct of its financial regulatory functions, introduced thus

Geof Mortlock argues the Reserve Bank is about as much use as a financial regulator as is a cricket umpire who is nearly blind and who understands little about the game

is this:

the recent release of bank capital regulation proposals that would see banks in New Zealand being required to hold a very high level of capital compared to other countries, with potentially adverse consequences for borrowers’ access to credit, an increase in interest rates and adverse impacts on the economy – and all on the basis of shockingly flimsy analysis by the Reserve Bank.

Quite.