There have been numerous articles in recent days about the fall in business confidence, as reflected in various survey measures. What, if anything, is it telling us? Why is it happening? What might turn the situation around, and so on? Both sides of politics have a strong interest in their own particular interpretation. On the one hand, general business confidence has tended to be weaker relative to actual outcomes under Labour than under National-led governments (if so, the falls might tell us nothing that we don’t already know – that we have a Labour-led government). And, on the other hand, (so the argument goes) the government is doing and saying quite a few things that many in the business community genuinely regard as inimical to growth, and thus it should be no surprise that sentiment is weaker now, and with it future growth prospects – for those who particularly want to gild the lily, especially relative to the stellar performance allegedly achieved in the later years of the previous government. As regular readers know, I treat that latter bit as laughable: productivity growth being almost non-existent, the relative size of the tradables sector having shrunk, business investment having been weak, and so on. Oh, and the housing situation got even worse.

(The IMF Board – whose assessment of New Zealand just dropped into my inbox – must be firmly of the “business just don’t like Labour” school, but then their assessment of the past, present, and future seems laughably detached from reality. Believe that assessment, and you’ll believe that – at least in per capita terms – things get even better from here, building on the “economic expansion with notable momentum” of the last half-dozen years.)

I’m not going to try to put myself in the minds of those answering these surveys but there seem plenty of reason to be rather pessimistic on the outlook from here. Some – perhaps many – are the responsibility of our government, but others are not. The global environment looks shakier than it has at least since the height of the euro crisis in 2012, with significant fragilities evident all over the place: in the euro-area itself, the ever-increasing uncertainty around Brexit, pressures in various large emerging market economies, rising US-driven trade tensions, the legacy of a debt-fuelled boom in China, and so on. And against that backdrop, few countries have much fiscal or monetary space to respond vigorously when the next downturn comes. Recognition of that is beginning to seep into general consciousness.

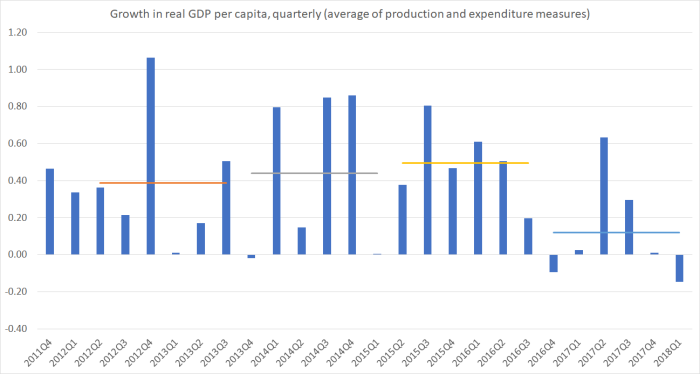

And it isn’t as if things have been going particularly well over the last couple of years. This chart shows GDP per capita growth, with the horizontal bars marking successive 18 months periods.

Perhaps the most recent weakness will end up getting revised away, but at the moment there doesn’t seem to be any particular reason to expect that. There has been little or no productivity growth, and very weak per capita income growth. It can take time for awareness of that sort of thing to take hold, especially in an election campaign session when National (party garnering the most business votes) was trying to tell a very upbeat story.

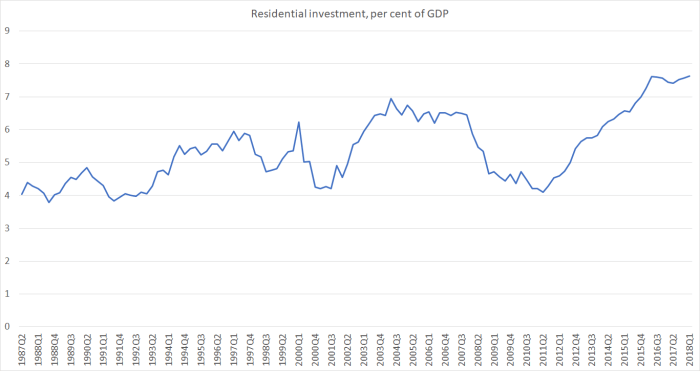

Perhaps not unrelatedly, the biggest proximate boost to growth in recent years has been house-building activity (related to earthquakes and the unexpected surge in the population).

How plausible is it to expect any sort of repeat of the last few years? Not very, I’d have said, both because the population pressure is beginning to ease, existing house price inflation seems to be stabilising (for now anyway) and the government has, despite fine words buried deep in the manifesto, done nothing to fix up the urban land market. If anything, housebuilding activity is likely to fall back somewhat in the next few years, and housebuilding typically plays a key proximate role in explaining short-term economic fluctuations.

Perhaps business investment could take its place. But consider:

- investment spending, other than on housing, is now 2 percentage points of GDP lower than it was at the previous peak (mid 2000s),

- the exchange rate, while have weakened a bit, is still in the range it has fluctuated within for the last 7 or 8 years,

- plenty of policy initiatives don’t look terribly conducive to encouraging more business investment:

- sustained and large increases in minimum wages (even if there is some spending to replace labour)

- concerns, fair or not, about other labour relations law changes,

- scrapping new oil and gas exploration licences,

- the uncertainty engendered by the shocking policy process used to make that decision, and (not mentioned in any other article I’ve seen)

- the government’s net-zero carbon emissions target, which their own consultative document (and their own independent consultants’ numbers) suggest will act as a material drag on the economy for several decades to come, if pursued with the sort of zeal key ministers at times suggest. (Of course, the previous government’s target would also have acted as a drag, but (a) many thought they weren’t entirely serious about it, and (b) the marginal costs of pushing further into this territory can be expected to increase quite substantially).

- the considerable uncertainties engendered by these targets (since few policy parameters, including expected carbon prices are remotely clear).

- if one wanted to focus on individuals, one might also feel uneasy that none of the top 4 ministers in the government command any confidence that they instinctively understand – or care greatly – what makes for a high-performing economy. Several of that top tier simply seem out of their depth, and few of the rest command much respect either. (I was no fan of the previous government but – rightly or not – business took a different view of Steven Joyce, Bill English, and John Key.)

I have also been interested in the comparisons with the “winter of discontent” that followed the election of the Labour-Alliance in late 1999. Some of that experience is quite nicely covered in this piece although I think the author is rather too optimistic about the current situation. As he notes, the level and tone of commentary on this new government is nothing like as vociferous as what greeted the incoming 1999 government (complete with plans to raise taxes, repeal and reform the Employment Contracts Act, repealing ACC privatisation, and installing Jim Anderton – opponent of most of the 80s reforms – as deputy Prime Minister). It hadn’t been that long since the polarising reform phase had ended. And while Michael Cullen was much more able than Grant Robertson, his acerbic tone – and all too obvious revelling in his own intelligence – only enhanced the tensions.

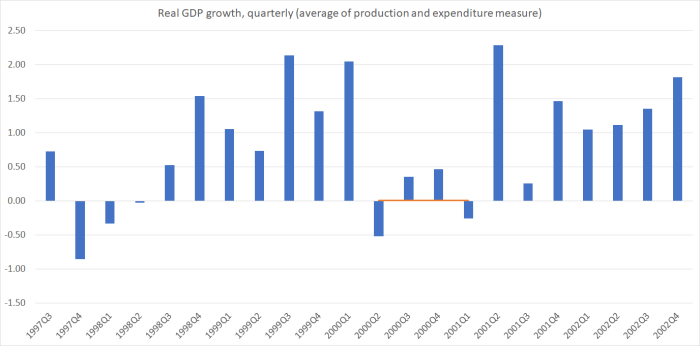

It was a tough period. Here is the chart of quarterly GDP growth (not per capita – annual population growth then was around 0.6 per cent).

GDP growth averaged zero for a year – before rebounding quite strongly. Some of that slowdown – which I don’t think we ever fully understood at the Reserve Bank – may have been a direct response to the change of government and proposed new policies. But it was far from being the only factor. It was still relatively early days in the recovery after the 1998 recession – so there was still lots of unutilised capacity – but there had been a big surge in investment during 1999 (even though a change of government was widely expected). At the time, two factors that seemed to play a part were the Y2K effect – every firm and its dog was devoting lots of resources to ensuring systems were robust – and building associated with the defence of the America’s Cup in Auckland in early 2000. Both were time-limited, and the relevant dates were very close to each other. Whatever the reason – and, as I say, I don’t think I’ve ever seen a particularly compelling analysis of that specific period – there was a (quite unexpected) slowdown in activity, and in particular in investment spending. Perhaps – well, quite probably – higher interest rates played a role – we raised the OCR by 200 basis points in six months from November 1999, none of it because of the change of government. It was our first go at actually adjusting official interest rates – the OCR was only introduced in early 1999 – and with hindsight, they do seem like rather aggressive moves.

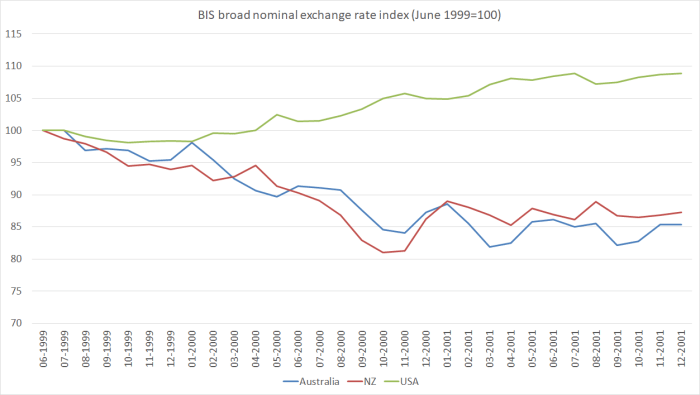

One factor that did play quite a large role then was the exchange rate, which fell very sharply in 1999 and 2000. Some vocal critics wanted to pin the blame on the change of government (expected and actual) – I recall one particularly strident Reserve Bank Board member bending my ear about the point at the time. But that story was simply wrong. Here is a chart of the BIS measures of the exchange rate for New Zealand, Australia, and the US.

The New Zealand and Australian exchange rates were basically tracking each other, with no obvious role for a “new left-wing government” effect. What was going on? Well, two things. First, and probably most importantly, although New Zealand was raising interest rates, so was the US, and indeed until now this was the only period since deregulation when our interest rates had matched those of the US. And, secondly, this was the era of “new economy” vs “old economy” – the NASDAQ peak in the dotcom boom peaked in March 2000, and capital was flowing towards these perceived new opportunities and away from “old economies” like Australia and New Zealand. That period proved quite shortlived, and by the start of 2001 the Fed was cutting interest rates and the US itself had entered a mild recession (not mirrored in either New Zealand or Australia).

Which brings me back to the observation earlier that – politics aside, and the pressure from one news cycle to the next – the current situation should be more concerning. There was a pause in growth then, of the sort we haven’t seen yet this time, but:

- the previous episode came early in a recovery phase not late,

- it came at a time when population pressures were quite weak, and there was a reasonable chance of an acceleration (as happened a year or two later),

- the global environment looks less promising (despite the dotcom bust in the US, much of Asia was recovering strongly after the crisis/recession of 1998),

- productivity growth over the previous few years had been reasonably good in th late 1990s,

- there were some specific, time-limited, factors that can be pointed to, contributing to the pause back then,

- whatever you think of the policies Labour brought in the 1999/2000, in terms of creating additional uncertainty and an additional drag of prospective growth well into the future, they were as nothing as compared to the implication of a net-zero emissions target,

and perhaps the biggest difference of them all is the real exchange rate. The current level is about 30 per cent higher than it was in 2000, and it had fallen a long way to get to those 2000 levels (and not on heightened risk concerns etc). Those falls created a credible prospect of new business investment in the tradables sectors. There is nothing comparable now, and we’ve probably exhausted the limits of domestic demand (especially residential investment) as a support for headline GDP growth.

One could add to the mix that if anything goes wrong, sourced here or abroad, there isn’t much capacity for macrostablisation policy to respond. Yes, the OCR could be cut – and probably already should have been, given the persistent undershoot of the target (another difference to 2000) – but the Bank is likely to be increasingly uneasy the further it cuts from here, and on its own estimates can’t cut more than about 250 basis points in total. And whatever the merits (or otherwise) of the 20 per cent debt target, it will come under new pressure in any downturn, and the (market and business) pressures to stick to it will only intensify in that climate – “show us your mettle, minister” will be the watchword.

I don’t think the private sector understand that this government has no ideological objection on working with with it.

The government would like to partner up with private providers to do the master planned housing projects, to provide lower cost housing prefabrication factories and to provide rapid transit and other trunk infrastructure.

I explain how this model could work for Christchurch here. But the same model could work for any growing city in NZ.

View at Medium.com

I believe the various announcements Cabinet Ministers such as Grant Roberton, Phil Twyford and Shane Jones have made in this space, indicate this is the government’s thinking on how to improve urban performance for NZ.

LikeLike

There is a difference between rhetoric and actual practical execution.

LikeLike

On RNZ101.4 the other day, a NZ prefab factory indicated that they could build in factories in NZ at $500 cheaper than the traditional on site build but it would still cost $2,300 per sqm. This a long way from the $1,200 per sqm that Phil Twyford touted that an overseas prefab could manufacture in factories for. It does not give confidence to local businesses to invest because it looks like all that work will go to overseas suppliers as we just can’t compete locally.

LikeLike

INteresting that you say that Brendon. I got a Labour Party brochure in my letterbox the other day, with lots of picture of the PM, and a “page” (one of five) on “Working to fix the housing crisis”. It talks about the foreign buyers ban, stopping selling state houses, the Healthy Homes guarantee, and Kiwibuild, but no mention at all of the land market, infrastructure or the like. As you know, I was never that optimistic as to what Labour would do in this area in govt – whether from choice or support partner constraints – but so far at least I’ve been pretty disappointed, even relative to those modest expectations.

LikeLike

Phil Twyford discusses infrastructure and land supply in a public meeting with property developers

LikeLike

Michael, as I had understood the dwelling consents figures, a problem has been totally inadequate numbers of dwellings built over the past decade.

This government is promising to build, and facilitate the building of, a lot more, houses mostly. You observe that “If anything, housebuilding activity is likely to fall back somewhat in the next few years, and housebuilding typically plays a key proximate role in explaining short-term economic fluctuations”.

You seem to be saying we are going to be building fewer dwellings over this and the next few years, while the Government is trumpeting that a lot more will be built, and seems to be putting in place some measures to encourage this.

Are you really saying house-building will be less of a GDP impact over hte next few years than it has been post the earthquakes?

LikeLike

I would be very surprised if housebuilding makes up as large a share of GDP in the next five years as it has in the last (and certainly the share won’t increase – boosting the growth rate all else equal – in the way it has in the last five years). For all the talk about insufficient house numbers, the data don’t really support that story. take Auckland for example where, for the time being at least, prices are more or less flat, which suggests a rough balance between supply and demand given prevailing regulation etc. the key thing getting ignored is land prices – the bulk of the inflation in house prices. As yet, the govt has done nothing to free up the land market, and you never here much from the PM or senior ministers about them doing so. If they did, then there would be a lot more effective demand for new houses+land, at the new lower prices. As it is, people seem to just squeeze in tighter – they can’t afford anything else at these extraordinary prices.

With population growth rates tailing off, and the Chch process more or less at an end, I’d then expect housebuilding rates to fall back a bit, even if we avoid a recession. If, for some reason, a recession happens then of course, the slump would be substantial – the interaction of falling incomes, tighter credit standards, borrower risk aversion, and some falls in existing house prices (essentially what we saw over 2008 to 2010).

LikeLike

KiwiBuild will have a significant effect on the property at multiples levels.

LikeLike

I was looking at a 1 bedroom 66sqm apartment with a carpark in DGZ offered at $599k. Initially I was quite keen to purchase because brand new builds in the area were priced around $750k. It was already clear to me that the impending Foreign Buyers ban was already putting downward pressure on prices of existing apartments competing with brand new builds. However I have not bought yet because I am anticipating further downward pressure on existing apartment dwellings.

Most of my other properties are larger sections that offer a number of extra dwellings. Having finally received CCC on my 3 site subdivision after 4 years from RMA to building consents to final CCC. I am somewhat reluctant to build. It was a painful process. With the government planning 10,000 houses a year, it is currently a wait and see approach. Instead I am now going through a insulation spendup in preparation for next year insulation compliance requirement and increasing rents by $50 to $100 each property to cover the increased insulation costs.

LikeLike

Correction: increasing rents by $50 to as much as $100 a week

LikeLike

Population growth rate tailing off, but not population growth. Then there are other factors that could lead to an increase in building houses. For example smaller families and more singles meaning potentially a greater demand for houses. A demand that is currently hidden by irrational housing costs. Personal experience is all things being equal children would prefer to leave home; it is just financial issues that keep so many adult children sharing with their parents. Then there are the houses that are dying of old age – my 1965 weatherboard house seemed OK when bought 15 years ago but now it is badly showing its age – soon all those 50 year old properties will need replacing. However I suspect the single biggest factor is the drift from the country to the city. School leavers are moving to the cities. Farm automation has killed the need for people but I suspect it is the universal use of modern media that makes living in the provinces seem so provincial for young people. When population moves it needs new accommodation.

My conclusion is residential building could increase dramatically if firstly they remove the cost of land (several solutions spring to mind) and secondly replace suing the council for a leaky home with a water-tight builders insurance (this would probably make the consenting process trivial).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Saw this on interest.co.nz in one of the comments. But unfortunately this can’t happen in NZ because the NZ courts have made Council fully liable for builders and professionals failures.

“I’m an engineer that worked in Canada. In Canada, I could approve almost anything. I was tasked with keeping my own records and might be subject to an audit from my association once in a while (if there was a complaint against me, or randomly every ~7-10 years). Councils more or less stayed out of my work. If something went wrong, I was personally accountable, I couldnt legally hide behind a corporation.

Here in NZ, I have to present all of my work neatly documented to council for approval. Moreover, if there are quick changes to be made on site, I have to fully document them and propose them to council for approval. All of this has to go through the proper channels at council and be approved. Council doesnt grant approvals easily. And often, the council staff reviewing my work don’t know anything about engineering. But, I have much less liability, as council more or less carries it all.

It’s incredibly frustrating and disempowering. Even worse, projects take about twice as long here to carry out. hourly fees are roughly the same. Guess who pays for it all?

And in the end, council holds everything up here, to review it all, even though they don’t know what they are reviewing. The person paying for the project has to fund all of this impotent bureaucracy, and when shit hits the fan, the taxpayer pays for all the screwups.

I think the entire system here needs an overhaul. Let the industry self regulate, but also force the liability onto the private sector. Force the businesses to carry functional insurance, force engineers to sign off on things personally, rather than behind a company that can be easily shut down. Let the professionals do their work, and make them stand behind it.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

You may well be right Michael, but your expectation runs counter to the political story, and layperson’s expectation, doesn’t it? I have looked at the latest SNZ graph of quarterly building work put in place. It’s a miserable relatively level red line from the turn of the millenium (May month numbers this year are at early 2000s May level for the first time since then), and if the present Government doesn’t do better over the next three years it will be difficult for most to understand.

LikeLike

I’m out of town today so can’t reply in detail, but the key thought is probably this: if building costs aren’t coming down, and land isn’t being freed up, the basic supply price of houses can’t be falling. Affordability is the issue on the demand side. So the govt can talk about lots more houses being built under its label, but there is no particular reason to think they won’t almost entirely displace building the private sector would otherwise have done.

But you are right, it isn’t the political narrative. And the lay story, about shortages of housing, isn’t wrong in one sense: people really would prefer more houses, but they can’t afford them at these (land) prices so there is no effective demand. At feasible supply prices of 3x income, I suspect there would be a lot more building.

The expected decline in the population growth rate also matters here.

LikeLike

Phil Twyford has just said that central govt is working on a national directive under the RMA to enable Akl council to free up height and density around transport nodes and corridors (reported from the Kiwibuild summit). I hope the work comes to something. Matt Prasad states “Heights and density in the unitary plan were a mediated outcome not necessarily best practice” https://twitter.com/matty_prasad/status/1014285731240407040

LikeLike

I haven’t seen any other reporting on this though. I really hope it happens.

LikeLike

With most of Auckland built on a volcanic field of 57 volcanoes, height and density could be problematic. Initially I was of the opinion that Auckland Planners were intentionally subjecting 40 million sqm of Viewshaft height limits for the unique view of each volcano from each public park as the primary reason, afterall it has been termed as Viewshaft height limits. However in the old district plans these were called Volcanic Sensitive Zones which is a more appropriate name. After the recent Hawaii eruption that have fluid lava flows that just would not stop overflowing and had a creeping damage to vast areas, perhaps Auckland Planners have got it right. We have a similar fluid lava under Aucklands many volcanoes which means technically, Auckland must remain low rise and low density, ideally single dwelling zones.

LikeLike