I’ve been struck again over the last few days by the determination of our “elites” – whether from the left-liberal end of the spectrum, or the (rather smaller) libertarian end – not to actually engage with the data on New Zealand’s experience of large scale immigration.

In their amusing tongue-in-cheek simplified retelling of English history, 1066 and all that, Sellars and Yeatman had most things classified as “a good thing” or “not a good thing”.

There seems to be a world view, straddling National, Labour and the Greens, and ACT as well, that in some sense “immigration is a ‘good thing'” and that is really all that needs to be said on the matter. Much the same goes for the media. The plebs just need to get with the programme – perhaps having it explained to them again, slowly and clearly this time, that immigration is a “good thing”. Any skepticism is too often deemed to reveal more about the character of the sceptic, than the merits of the economic case.

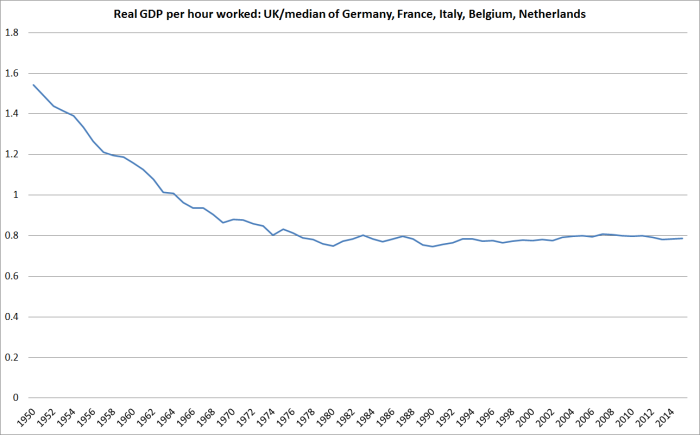

There is a respectable theoretical argument (at least within the narrow confines of economics) to be made for an open borders policy. But the fact that no political party I’m aware of – here or abroad – actually argues for such a policy is probably quite telling. Within the EU, there is a particularly respectable case for open borders – the EU-enthusiasts see the countries of Europe as being on a transition to a political union. Only brutal authoritarian countries – think China – want to control migration of citizens within their own country. But, as it happens, most Brits didn’t want to be part of an EU political union, preferring to govern themselves. Polls suggest citizens in most other EU countries also don’t want such a union.

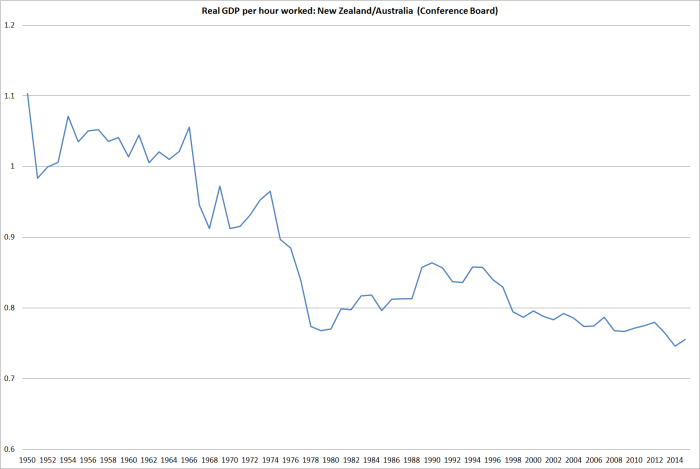

Even without political union, there can be a reasonable case for an easy flow of people across borders. New Zealand and Australia are two different countries, and that doesn’t seem likely to change. And yet there have never been direct immigration restrictions on people moving among the various colonies (pre 1901) or between the Commonwealth of Australia and New Zealand (since then). In practical terms, the barriers to moving – especially from New Zealand to Australia – have been getting higher in the last few decades, as Australian welfare provisions etc and citizenship have become progressively less readily available to New Zealanders. On my reckoning, New Zealanders have gained considerably from this ability to move to Australia, especially as the large income and productivity gaps have opened up in the last 50 years. Some New Zealanders relocated and took direct advantage of the higher incomes and better opportunities abroad. The rest of us benefited – at least in principle – because the departures from this land of (apparently) diminished opportunities eased the pressure on living standards here. Whether Australians have benefited from the easy flow of people across the Tasman is more arguable. There are reasonable arguments (and, thus, models) for small gains, small losses, and not much difference at all.

Even within the context of a system of immigration controls, there can be a variety of motives for allowing immigration. There is the humanitarian perspective that governs refugee policy. We don’t take refugees because it is good for us, but because it is good for them – people whose homelands have become impossibly difficult. If the refugee intake ends up benefiting us economically that is a bonus, but it isn’t – or shouldn’t be – what drives us. And, of course, we allow New Zealanders who marry abroad to bring their spouse home, and to become a New Zealander. Again, there isn’t an economic motivation behind those provisions. And some countries have real problems controlling their borders, and get stuck with people they never intended to allow in.

But we do control our borders and the bulk of New Zealand’s non-citizen immigration programme has an economic focus. MBIE, and the government, have described the immigration programme as a “critical economic enabler” for New Zealand – a phrase which sounds sillier, and emptier, each time I write it, but which is at least honest. We take migrants – lots of them (three times the per capita inflow in the US) – on the hypothesis that doing so will help New Zealanders economically over the medium to long-term. We certainly needed “critical economic enablers”, so poor has our economic performance been over the post World War Two decades. And there are plausible hypotheses for how immigration can help, at least in the abstract.

But several decades on, surely the advocates, administrators, and cheer leaders of the programme should be able to point to economic gains for New Zealanders? It doesn’t seem an unreasonable request, given the economics-based case made for the programme. The presence of a wider range of ethnic restaurants, or the success of the All Blacks, are all very interesting – although, to be honest, I hadn’t seen too many new English restaurants (the UK is still the source of more new residents than any other country) – but that isn’t the case that has been made. New Zealanders are supposed to have been made better off economically by large scale immigration. And if there is evidence of those gains, the champions of the programme are strangely reluctant to cite it.

And so we have Liam Dann in the Herald this morning

Australians have been panicking about immigrants and to some extent their loss has been our gain.

Migration-driven GDP growth through a period of commodity price downturn has been a timely break for our economy.

….

There are risks that high immigration disenfranchises those at the bottom of the social ladder.

We need to ensure we have social policy to protect people from losing out and turning their anger towards migrants. We need to remember the current surge is not driven just by the more highly visible arrivals of different culture and ethnicity.

It is being driven by New Zealand passport holders.

History tells us this wave will not last. And that when it passes it will have left this country richer and stronger.

It is a strange argument. After all, had the economy of our largest trading partner been doing better, presumably that would have helped our economy not hurt it. And if demand had been weak here – as actually it has been – we could have had lower interest rates and a lower exchange rate, the latter in particular would likely to have been helpful.

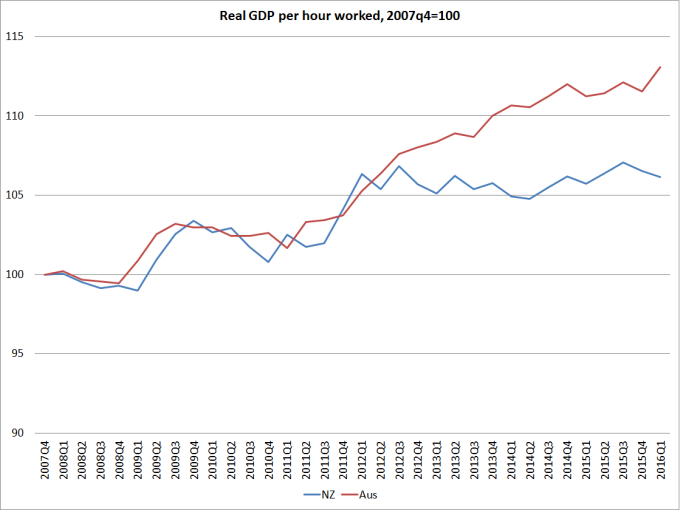

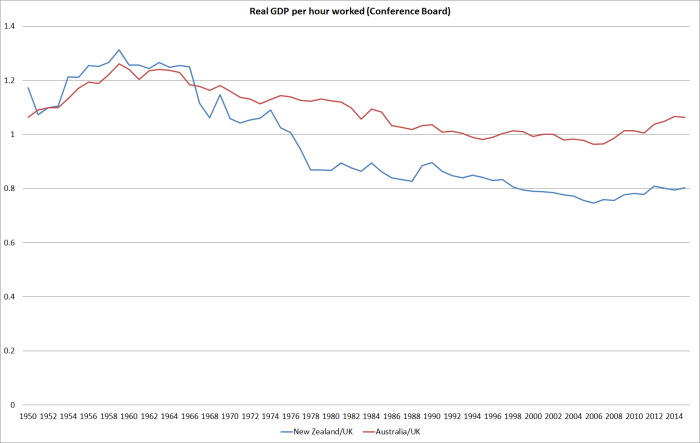

And then, apparently confusing the variability in the NZ citizen immigration with the baseline large inflow of non-citizen migrants, he worries about people at the bottom “losing out”. But this appears to be only about perceptions because he knows that when the current immigration surge ends “it will have left this country richer and stronger”. That is, certainly, the logic behind the immigration programme. But where is the evidence? There is no sign that the income or productivity gaps between New Zealand and Australia are closing. They haven’t closed after the previous waves of immigration either. It seems to be based on little more than a wish – and that same underlying belief that somehow high immigration is a “good thing”.

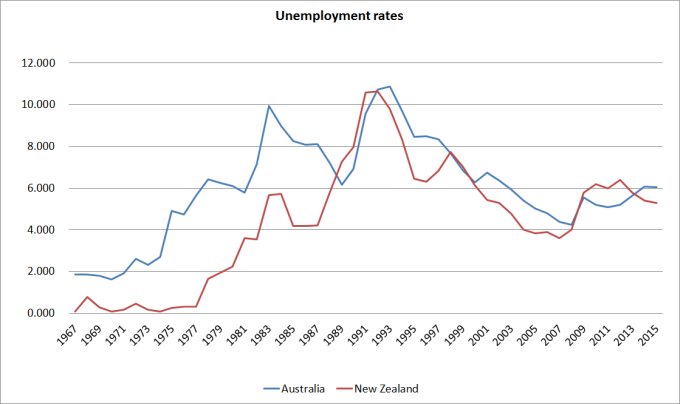

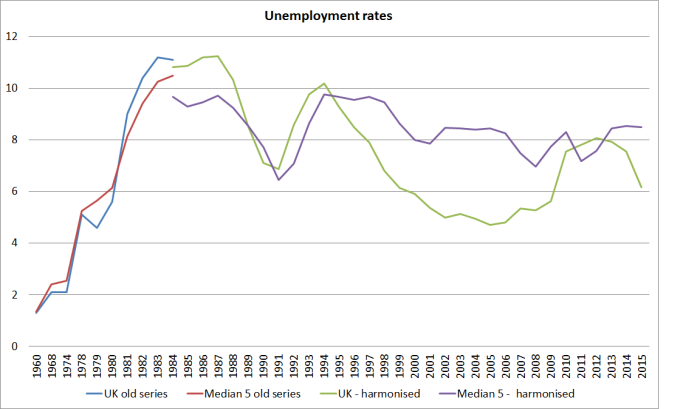

The Prime Minister on Q&A yesterday was no better. Corin Dann put to the Prime Minister the case recently made by leading businessman (and economist) Kerry McDonald that high rates of immigration to New Zealand are quite damaging. The Prime Minister responded that he “didn’t think the evidence bears that out”. But he offered no evidence at all. He mentioned wage increases in New Zealand, but when the interviewer pointed out that there was still a very large gap to Australia, all the Prime Minister could offer was the defensive “well, we’ve trying to close that gap for a long time” (really?) and “most New Zealanders would say we are making some progress”. If the numbers supported his case, presumably he’d have quoted them. They just don’t. As I illustrated on Saturday, the gaps to Australia have just continued to widen – not by large amounts in any one years, but little by little. There is still a net outflow of New Zealanders to Australia, and if it isn’t as large as it was that seems to be mostly because the Australian labour market is tougher than it was, rather than that New Zealand is doing well. (Again, as I illustrated on Saturday, both New Zealand and Australia have relatively high unemployment rates at present, and the gap in our favour is no larger than it was on average over the last couple of decades).

The Prime Minister was challenged on political spin in the interview, and he acknowledged that both governments and oppositions do it. It was certainly on display in the answers on immigration. The Prime Minister likes strong immigration because it is a “vote of confidence in New Zealand”. Which might sound good for the first five seconds, until one remembers that for New Zealanders not leaving it is mostly that Australia isn’t doing that well either right now, and for those coming from emerging countries, New Zealand is richer than, say, India, China or the Philippines. None of that tells one anything about whether New Zealanders are gaining from the large scale programme. Similarly, the PM fell back on the “house prices are a quality problem” type of argument – suggesting that Auckland was no different than cities around the advanced world with population pressures. Perhaps he could check out Atlanta and Houston some time.

In a serious interview, on a major issue, the Prime Minister was simply unable to offer any evidence – or even good arguments – for how New Zealanders were actually benefiting from the immigration programme that he continues to run (the same programme his predecessors ran). It should be a clue that there just aren’t such benefits. With all the resources of the state at his disposal, including state-funded research programmes for advocates of the current policy, and he can’t articulate the benefits for New Zealanders. Something seems wrong.

This week’s Listener – house journal for the left-liberal establishment – had a lot of advocacy material on (the perils and woes of) Brexit – epitomized perhaps in the column of the Otago university professor who concluded

Enough is enough. The British Government must halt its plans to proceed with Brexit and organize a second legally binding referendum to determine Britain’s future relations with the EU.

Vote again – and again – until the people deliver the approved answer.

Political columnist Jane Clifton dealt with immigration issue. She observed

But the bitterest Brexit realisation is the damage that ensues when governments fail to “sell” immigration. That’s the most urgent lesson for our MPs to swat up, because anti-immigrant sentiment is seldom far from the surface here. A sizeable bloc of British voterdom simply does not believe that immigrants enrich their country and stoke economic growth and job opportunities. And who can blame them, since in many long-term depressed areas, there’s precious little evidence of it.

Here, immigrants are increasingly copping referred anxiety about Auckland’s growing pains. Rather than document and illustrate the benefits of migration, the Government simply refuses to engage on any other level than to call the anxious xenophobic or racist

I’m not sure that last phrase is correct. So far, to the extent there has been a discussion, it has mostly been free of that sort of thing. [UPDATE: That was before I saw these comments from the Minister of Immigration.] But the more general point holds. The government simply does not, and perhaps cannot, illustrate the benefits of the programme for New Zealanders as a whole. The alternative approach seems to be instead to whistle to keep spirits up, and attempt to spin the problems into a story of some sort of success. If there really is now a robust case to be made for current policy, it should be beneath our government to rely on such feeble assertions. Clifton herself, of course, seems unable to recognise the possibility that there may not be such benefits to New Zealanders – that it might just be an economic experiment that has failed.

These days, we have serious figures from the centre-right, such as Don Brash and Kerry McDonald, arguing that our immigration policy is flawed, and probably damaging to the fortunes of New Zealanders, but our media and political elites remain enthralled with an “immigration is a good thing” mentality, unwilling or unable to engage with the specifics of New Zealand’s circumstances, location, and general ongoing economic underperformance.

And it carries across to housing policy. In the last week, there have been a couple of serious contributions to the debate as to “what should be done” about housing, from, Eric Crampton and Arthur Grimes (and here). I agree with a fair amount of Crampton’s piece, and disagree with a fair amount of Grimes’s – which is notable for wanting to ride roughshod over the rights and interests or existing residents. But where they unite – from the left-liberal end of the spectrum and the libertarian end – is in avoiding any serious discussion about the high baseline target rate of immigration. Now, I’ve always argued that as a first best we should try to sort of our housing supply issues – Atlanta and Houston have – and ideally have a separate conversation about immigration (since my arguments about the damage immigration policy seems to be doing are not at all reliant on house price stories). And if there were any evidence that rapid inward migration was in fact boosting the fortunes of New Zealanders as a whole that might be a particularly robust case. But…..there is none, or certainly none that the advocates have advanced. Instead, we know that Auckland’s GDP per capita has been falling relative to that in the rest of the country for 15 years (as far back as the data go) and the margin by which GDP per capita in Auckland exceeds that in the rest of the country is now very low by international standards. And if there is no sign that rapid immigration-driven population growth is helping lift New Zealanders’ income, while the political difficulties of fixing housing supply remain large, the case for cutting back the target inflow is strong. Doing so would immediately ease house price pressures – and without riding roughshod over property rights through use of compulsory acquisition powers that the government and economists now seem to favour – and at worst not harm our medium-term income prospects.

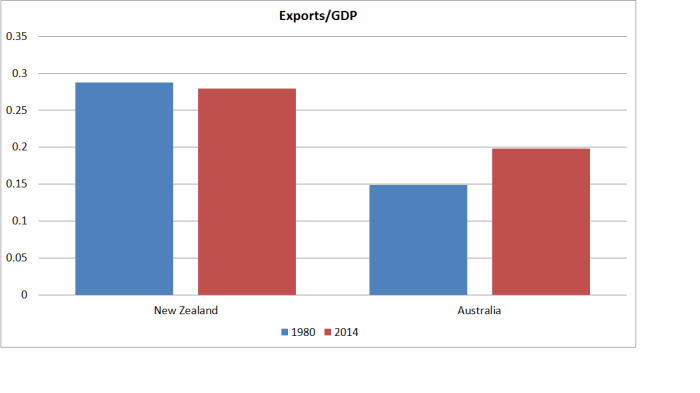

As a reminder, the OECD produced new data only last week suggesting that the skill levels of adults in New Zealand are among the very highest anywhere (and that, as in most advanced countries, the skill levels of the average immigrant are a bit lower than those of the native-born. To the extent we’ve managed to grow our exports – the foundation of long-term prosperity – it has mostly been in natural resource based industries (complemented by the heavily subsidized film industry and the subsidized export education industry) where numbers of people just don’t help much, if at all. There is no compelling economic case – and recall it is economics that supposedly drives our immigration policy – for using policy to deliver lots more people to New Zealand. The Prime Minister, the leader of the Opposition, the Greens leaders all seem to disagree, as do the media establishment, but none of them can offer a clear simple straightforward data-driven explanation for why.

I’m not sure if there is a risk of a serious social/political backlash of the sort senior lawyer and former ACT MP Stephen Franks talks of. But I certainly hope there is an economic backlash before too long. The alternative is, most likely, that our long slow relative decline continues – and any other decent policies we adopt, and the skills and capabilities that our people possess, are constantly battling up hill, in face of an ideology (no doubt mostly well-intentioned) convinced that “immigration is a ‘good thing’ for New Zealand”. In economic terms it doesn’t seem to have been so for a long time.

In a Listener article a few weeks ago, my former colleague (and New Zealand historian) Matthew Wright was writing about the early pre-1769 history of New Zealand. One line in particular caught my eye:

New Zealand was the last large habitable land mass on Earth reached by humanity. The long journey of our species from Africa’s Rift Valley into the wider world ended, it seems, on the Wairau Bar.

New Zealand has produced pretty good living standards, at such great distance, for a small number of people. In the halcyon days – when our relative performance was at its best – we had a quarter the population we now have. New Zealanders saw something going wrong decades ago and started leaving in large numbers – in outflows that, as a share of the population, are really large by past international standards – and haven’t yet seen fit to reverse that judgements. Distance isn’t dead, but our government’s immigration policy – in thrall to the ideology – seems to assume that wishing it so can make it so. We need to be much more cautious, and evidence/experience driven, in continuing to pursue an economic case for an ever-larger population

New Zealand’s export share of GDP hasn’t changed in 35 years.

New Zealand’s export share of GDP hasn’t changed in 35 years.