Early last month, just before I headed off to the beach, a couple of readers forwarded me references to an article written in about 1992 by the late Professor (of Maori Studies at the University of Auckland) Ranginui Walker, headed New Zealand Immigration and the Political Economy. Having done no more than glance through it, I included a link to the article at the end of a post and went on holiday.

On my return, I sat down and read Walker’s article more carefully, including in the light of the new New Zealand Initiative advocacy report on immigration, which touches lightly on issues of how we should think about New Zealand immigration policy in light of the place of Maori in New Zealand.

Walker’s piece is interesting for two things: first, that is was written in the quite early days of something like the current immigration policy (policy having been reworked considerably over the 1986 to 1991 period), and second because it is a distinctively Maori-influenced perspective. (Incidentally, Walker’s biographer was Prof Paul Spoonley, now a leading (and MBIE-funded) pro-immigration academic. It would be interesting to know what Spoonley makes of Walker’s somewhat sceptical assessment of New Zealand’s immigration policy written at a time when the target non-citizen inflows were smaller than they are now (and the stock of migrants was much smaller than it is now).)

Walker argued that modern immigration policy was a matter covered by the Treaty of Waitangi, consistent with his attempt to re-insert the Treaty into contemporary policymaking. He cited words from the preamble to the Treaty

The original charter for immigration into New Zealand is in the preamble of the Treaty of Waitangi. There, it states that Her Majesty Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom:

“has deemed it necessary, in consequence of the great number of Her Majesty’s subjects who have already settled in New Zealand, and the rapid extension of Emigration from both Europe and Australia which is still in progress, to constitute and appoint a functionary properly authorized to treat with the Aborigines of New Zealand for the recognition of her Majesty’s sovereign authority over the whole or any part of those islands.”

And went on to argue that

The present generation of Maori leaders abide by the agreement of their ancestors to allow immigration into New Zealand from the countries nominated in the preamble of the treaty, namely Europe, Australia and the United Kingdom. But, for any variation of that agreement to be validated, they expect the Government to consult them as the descendants of the Crown’s treaty partner.

Asian immigration, in particular, so it was argued, required formal consultation between the Crown and Maori. You might find that a stretch – I do – but it does focus attention on the question of just what Maori leaders in the first half of the 19th century were agreeing to when it came to immigration. I suspect it wasn’t a set of policies that would reduce Maori to a small minority, marginalised politically, in their own land.

British and settler control over New Zealand developed gradually, from the first European settlement at Oihi through to the end of Maori/land wars in the early 1870s, by some mix of acquiescence, agreement (notably the Treaty), annexation – and military defence/conquest. I wrote a post last year drawing attention to a lecture by 19th century Premier Sir Julius Vogel who had noted unashamedly, looking back on the origins of his own huge public works and immigration policy, the role played by a desire to secure the North Island militarily, and so shift the population balance that European dominance of New Zealand would be secured for the future.

I will tell you the real facts, and I think I may say there are only two or three men now living who can speak with equal authority. The Public Works’ Policy seemed to the Government the sole alternative to a war of extermination with the natives. It comprised the construction of railways and roads, and the introduction of a large number of European immigrants. The Government argued that if they could greatly increase the population of the North Island and open up the means of communication through the Island, and at the same time give employment to the Maoris, and make their lands really valuable, they would render impossible any future war on a large scale. They recognised that in point of humanitarianism there was no comparison between the peaceful and warlike alternatives.

In the almost 150 years since then, there have been a variety of motivations espoused for promoting immigration to New Zealand – including (external) defence, relieving population pressures in Britain, sharing the great opportunities here, possible economies of scale, and more latterly encouraging greater diversity and encouraging possible productivity spillovers. But whatever the argument, the effect of immigration policy has consistently been to reduce the relative place of Maori in New Zealand. Non-citizen immigrants are almost inevitably non-Maori, and in a unitary democracy, overall voter numbers count. Each immigrant lowers the relative weight on Maori in decisionmaking in New Zealand. And to the extent that immigrants assimilate, it typical isn’t with Maori culture.

In his article, Ranginui Walker touches on one of the ways in which policymakers have sought to avoid confronting the issue. Writing of the 1986 review of immigration policy he notes

The review asserted that New Zealand is a country of immigrants, including the Maori, thus denying their prior right of discovery and millennial occupation of the land. Defining the Maori as immigrants negates their first-nation status as people of the land by lumping them in with the European immigrants who took over the country, as well as later immigrants from the Pacific Rim. Furthermore, the review disguised the monocultural and Euro-centric control over the governing institutions of the country by claiming that immigration has molded the national character as a multi-cultural Pacific country. This multi-cultural ideology is a direct negation of the Maori assertion of the primacy of biculturalism.

In other words, if Maori are just another minority there is no distinctive place, or no particular need to be sensitive to the implications of immigration policy for them.

A few years later, the Business Roundtable (forerunner to the New Zealand Initiative) commissioned Australian-academic Wolfgang Kaspar to write a paper on immigration policy in a New Zealand context. Kaspar – and the Roundtable – were dead keen on freeing up immigraton, seeing it as one important element in a strategy to lift New Zealand’s economic and productivity performance. Commenting on how Kaspar treats the Maori issue, Walker wrote

Kaspar’s views on Maori policy are also a matter for concern. With few exceptions, most Maori would reject his sooth-saying that they should not fear becoming a smaller minority in a situation where land and resources would be “competed away.” Like Job’s comforters, he says: “They (Maori) could instead live in a nation of many minorities where the Maori minority fitted in much better as an equal social group.” Kaspar’s view is advanced with the ignorance and naivete of the outsider who knows nothing of the 150-year struggle of the Maori against an unjust colonial regime. The reduction of the Maori to a position as one of many minorities negates their status as the people of the land with bi-cultural treaty rights and enables the government to neutralize their claims for justice more effectively than it does now. Furthermore, new migrants have no commitment to the treaty. For these reasons, the ideology of multiculturalism as a rationale for immigration must be rejected. Although its primary rationale is economic, the government’s immigration policy must be seen for what it is — a covert strategy to suppress the counter-hegemonic struggle of the Maori by swamping them with outsiders who are not obliged to them by the treaty.

One doesn’t need to be comfortable with the rhetoric – I’m not – to see Walker’s point. Whether by design (less probably now) or as a side-effect that the policy designers are largely indifferent to, large scale immigration simply reduces the relative significance of Maori in New Zealand. It has done that in new ways in recent decades as much of the immigration has been non-Anglo. For decades, immigration was mostly British, which left Maori as a small minority in their own country, but as at least the only “other” group. Modern migration patterns risk treating Maori as simply one minority among many – perhaps even, in time, with outcomes similar to (say) California where there is no longer any majority ethnicity.

Some of Walker’s article is now quite dated, but I think it is still worth reading if only because such perspectives don’t seem to get much airplay in the mainstream policy discussions. And when occasionally people do make the point about large scale immigration undermining the role of Maori and the Treaty, they are often simply batted away with rather glib reassurances that today’s politicians – who can make no commitments about how politics plays out 20 years or more hence – simply can’t back up.

(Although it isn’t my focus today, the first person to refer me to the Walker article highlighted this quote about the emphasis on large scale immigration to New Zealand

this policy does not take into account the fact that New Zealand is a primary producing country, it is resource poor in terms of minerals and oil, and is the most distantly placed country from world markets. It is difficult to produce competitively priced manufactured goods with the plussage of high freight costs on top of manufacturing costs.

Walker wasn’t an economist, but his observation is passing doesn’t seem to have been undermined by developments in the last 25 years, in which New Zealand’s overall economic/productivity performance has languished, despite the huge influx of new people.)

Last week, the New Zealand Initiative released their advocacy report, making the case for continued – or perhaps even increased – high levels of non-citizen immigration. It is an unsatisfactory report in several respects – for example, the subtitle “Why migrants make good kiwis” seems to rather deliberately(?) miss the point that should guide policy; do migrants make existing New Zealanders better off – and I’ll have quite a bit to say about various aspects of it over the next week or two. But today I just wanted to focus on the treatment of the Maori dimension.

As the report notes

Many Maori too are concerned about immigration, seeing it as a threat to their unique position as the first people to settle in New Zealand

and

The Election Survey reveals that Māori are significantly less favourable towards immigration than other New Zealanders, and Māori are significantly more likely to want reduced immigration numbers. They are also less likely to think immigration is good for the economy, and more likely to see immigration as a threat. This finding remains even after controlling for age, religion, marital status, home ownership, household income, education, gender, and survey year.

The authors note

This is clearly a concern for New Zealand, where Māori and the Treaty of Waitangi occupy a special cultural and constitutional role in society and national identity. Given the low barriers to obtaining voting rights in New Zealand, there may be a fear that allowing migrants to express these views at the ballot box would dilute Māoridom’s special standing.

That is all fine, but what sort of response do they propose?

The range of policy responses to this problem are fairly limited. Cultural education programmes for migrants may sound appealing, but it is unclear how successful they would be in changing views. Some migrants may simply see it as a tick box exercise to be endured to gain entry into the country, and may not have the intended effect on

migrant attitudes towards Māori and their place in New Zealand.

Indeed, and even if it it had the “intended effect” that wouldn’t alter the inevitable shift in the population balance. Maori – like others – might reasonably be assumed to want power/influence, not just understanding or consideration.

We have also considered a values statement, such as the one used in Australia. All visitors to the country are required to sign this document, affirming to abide by Australia’s largely Western values. Although this idea is appealing, it has two main weaknesses. First, New Zealand has yet to formally define its cultural values. Unlike Australia, or many other nation states, New Zealand does not have a single constitutional document. Instead, New Zealand’s constitutional laws are found in numerous documents, including the Constitution Act 1986, the Treaty of Waitangi, the Acts of Parliament, and so on. This allows the nation state of New Zealand to function, but does little to define what it is to be a New Zealander, and what set of national values need be upheld. Until this is done, it would be difficult to craft a robust and useful values statement. Even if it were possible, without constitutional protection, it would be subject to change according to political whim. Second, any values statement would still suffer from the pro forma weakness that a cultural education programme is subject to.

I don’t disagree that a “values statement” isn’t the answer, partly because in a bi-cultural nation there will be differing values – things that count, ways of seeing and doing things – even between the two cultures. But they go on.

A partial answer to this problem may be to shift the burden from the immigration system to the education system. The national curriculum, which acts as a reference guide for schools in New Zealand, places significant emphasis on learning Te Reo and the cultural practices of Māori. This may do little to address concerns about the attitudes primary migrants have towards Māori in New Zealand, but may influence the attitudes of second generation migrants. This is far from a complete solution, and monitoring attitudes of migrants to Māori, and vice versa, is advisable.

Indoctrination by the education system would seem equally likely to provoke backlashes, and – of course – does nothing to deal with the population imbalance issue. As the final rather limp sentence concedes, the report hasn’t actually got much to offer on this issue at all. They go on to conclude

There are also cultural dilution concerns of the Māori community regarding high levels of immigration threatening their unique constitutional position in New Zealand. These areas require attention from policymakers if the current rates of immigration are to be maintained.

But surely if think-tank reports are to be of any real value they need to confront these issues and offer serious solutions, not just kick the issue back to busy and hard-pressed policymakers?

By the time we get to the conclusion of the whole report, things are weaker still

Māori views on immigration policy should be welcomed. A more inclusive process is needed to instruct migrants on the key place Māori hold in New Zealand society.

It is both condescending in tone – both towards Maori and to migrants – while not actually substantively addressing the real issues, which aren’t just about sensitivity, but about power.

It is difficult not to conclude that in putting the report together the New Zealand Initiative had a strong prior view on the merits of large scale immigration globally, but could do no more than handwaving when it came to an important consideration in thinking about immigration policy and its implication in New Zealand. Of course, libertarians – as most of the Initiative people would probably claim to be, or accept description as – tend to have little sense of national identity or sub-national cultural identity; their analysis all tends to proceed at the level of the individual. But most citizens, and voters, don’t share that sort of perspective.

I don’t want to sound like a bleeding heart liberal in writing this, or to suggest a degree of identification with, or interest in, Maori issues and culture which I don’t actually have. My family have been here since around 1850, but I have no family ties with Maori, whether by blood or by marriage, and am quietly proud of my own Anglo heritage. In many respects I probably identify more easily with people and cultures in other traditionally Anglo countries than I do with Maori. But this seems to me a basic issue of fairness, including a recognition that (empirically), there is such a meaningful group as Maori, and that on average they see some – but far from all – issues differently than non-Maori. No doubt there is about as much diversity among Maori as there is, say, among Anglo New Zealanders, but the differing identities are meaningful and show up in various places, including in voting behaviour. And the inescapable point remains that New Zealand is the only long-term home of Maori.

I’m not one for apologising for history, and of course we can’t change history. But current policies changes the present and especially the future. Every temperate-climate region in the Americas and Australasia saw indigenous populations swamped in the last few centuries – between the power of the gun, and the prospects of greater prosperity that superior technology and economic institutions offered. Compared with, say, Canada, Australia, the United States, and Argentina, Uruguay and Chile, the indigenous population remained a larger share of the total in New Zealand.

This isn’t mostly a post about economics. It is impossible to do a controlled experiment, but I think there is little doubt that the indigenous populations of all those countries of European settlement are better off economically today than they’d have been without the European migration – even though in each of those countries indigenous populations tend to underperform other citizens economically. But, those gains have been made, and at what cost have they come in terms of self-determination and control? It isn’t easy for members of majority populations to appreciate what it must mean for a group to have become a disempowered minority in their own land. For some it is probably not an issue at all, for others perhaps it is of prime importance, for most perhaps somewhere in between, important at some times and on some issues, and not important at all on others.

If there were demonstrably large economic gains now, to existing New Zealanders, from continued (or increased) large scale immigration there might be some hard choices to make. Perhaps many Maori might even accept a further diminution of their relative position, as the price of much greater prosperty. But there is simply no evidence of such economic gains – whether in the New Zealand Initiative report or in other analysis of the New Zealand position. If so, why should we ask of – or simply impose on (we don’t have a federal system, with blocking power to minorities) – Maori New Zealanders a continuing rapid undermining of their relative position in the population, and in voting influence in New Zealand?

Much of this comes to, as in many ways it always has, fairly crude power politics. But the quality of a democracy should be judged in significant part by how it protects, and provides vehicles for the representation of the interests of, minorities. A minority population, that was once the entire population of New Zealand, seems to have a reasonable claim to a particular interest in that regard. Advocates of large scale immigration to New Zealand – whether politicians or think tanks or business people- might reasonably be asked to confront the issue, and our history, more directly.

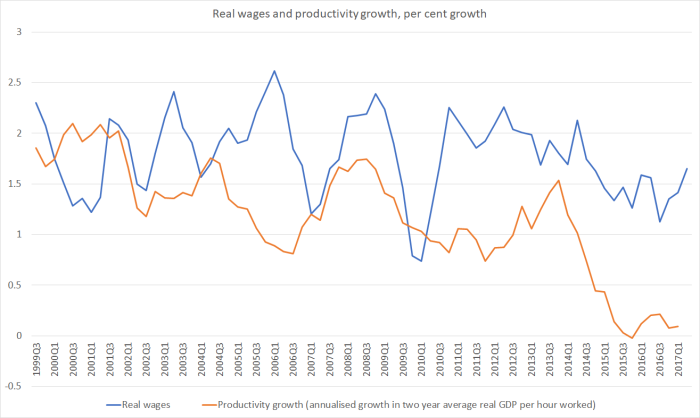

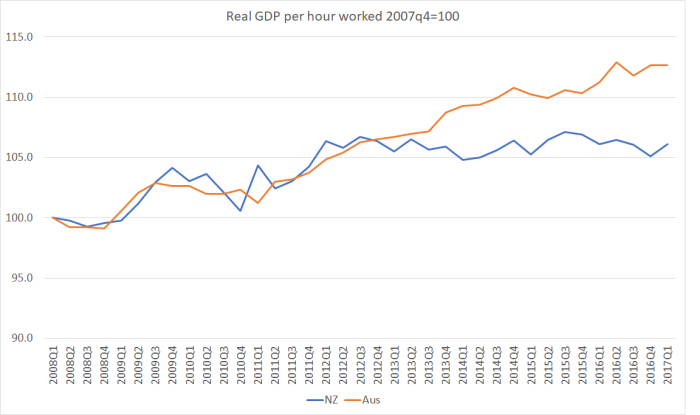

Not only have we had no labour productivity growth for five years, but our near-neighbour Australia – which the government was once willing to talk about catching up to – has gone on generating continuing labour productivity gains. Yes, there has been a productivity growth slowdown in much of the advanced world, dating back to around 2005. But our additional and more recent slowdown – well, dead stop really – looks like something different, and probably directly attributable to New Zealand specific factors. Things New Zealand governments have responsibility for responding to.

Not only have we had no labour productivity growth for five years, but our near-neighbour Australia – which the government was once willing to talk about catching up to – has gone on generating continuing labour productivity gains. Yes, there has been a productivity growth slowdown in much of the advanced world, dating back to around 2005. But our additional and more recent slowdown – well, dead stop really – looks like something different, and probably directly attributable to New Zealand specific factors. Things New Zealand governments have responsibility for responding to.

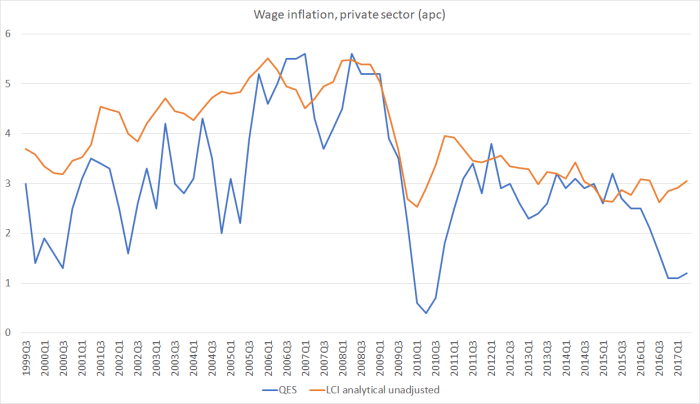

No economic analyst thinks wage inflation is anything like as volatile as the blue line – in fact, wage stickiness, and persistence in wage-setting patterns is one of the features of modern market economies.

No economic analyst thinks wage inflation is anything like as volatile as the blue line – in fact, wage stickiness, and persistence in wage-setting patterns is one of the features of modern market economies.