The Prime Minister’s speech on Sunday has attracted quite a lot of, generally not very favourable, attention. I was interested in a few things that were there, and a few others that weren’t, particularly when compared to the Speech from the Throne that inaugurated the government’s programme last November.

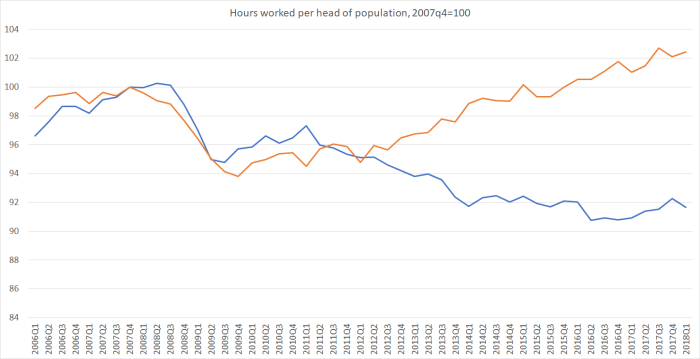

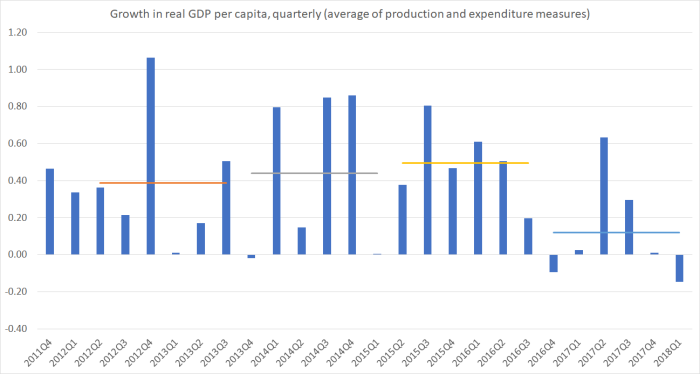

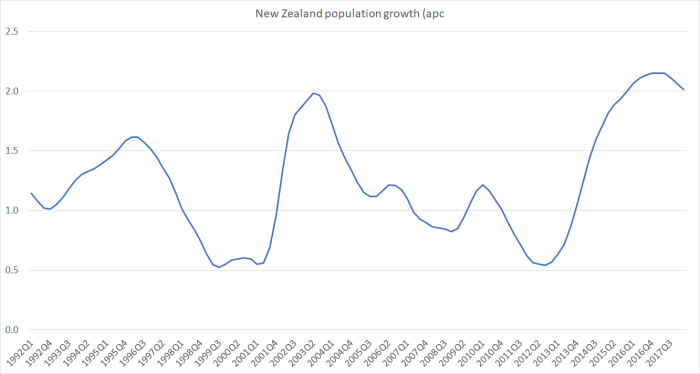

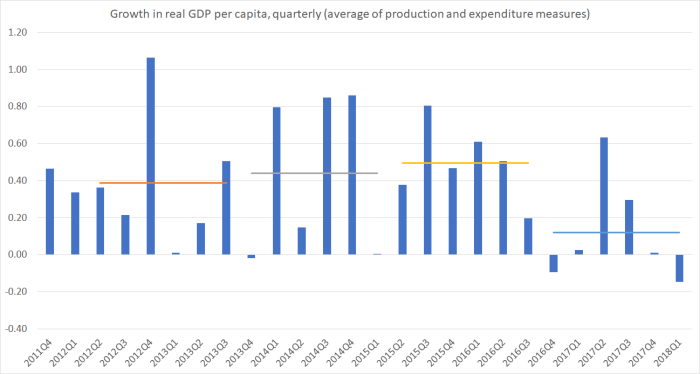

The first was the apparent lack of ambition around the economy. The Prime Minister continues to repeat the meaningless claim that “we’ve enjoyed enviable GDP growth in recent years”, as if headline GDP – as distinct from GDP per capita or GDP per hour worked – means anything at all. Here’s the track record: it has been pretty poor over the last couple of years (we’ll get an update on Thursday).

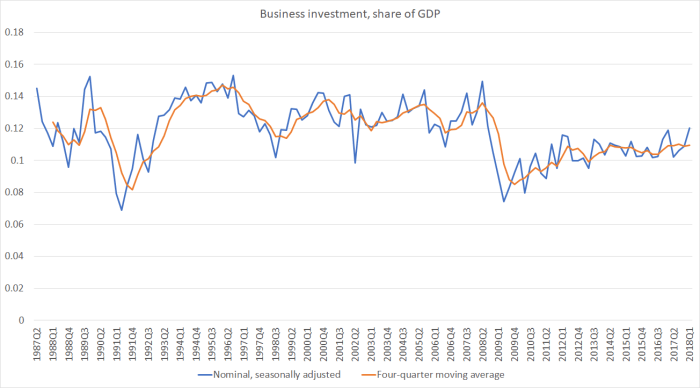

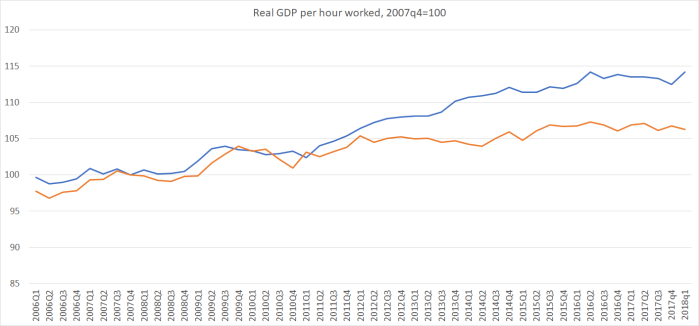

Productivity growth has been even worse, and for longer. Here, for example, is the comparison with Australia.

The Prime Minister seems to sort of know there is an issue.

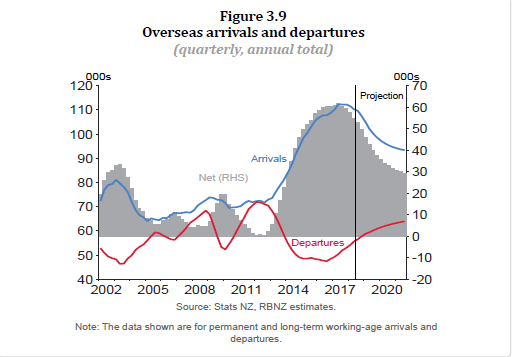

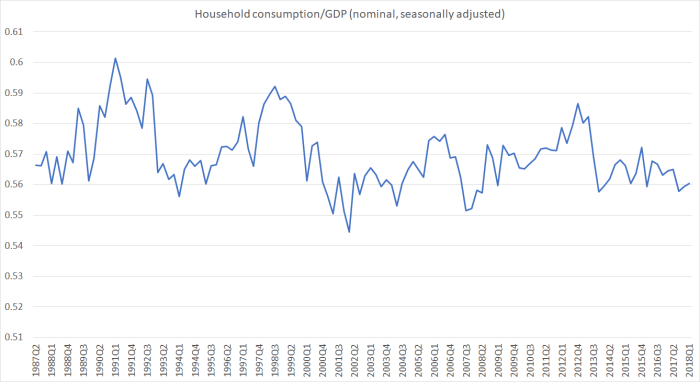

We cannot continue to rely on an economy built on population growth, an overheated housing market and volatile commodity markets. It’s not sustainable, and it risks wasting our potential.

That’s why our first priority is to grow and share more fairly New Zealand’s prosperity.

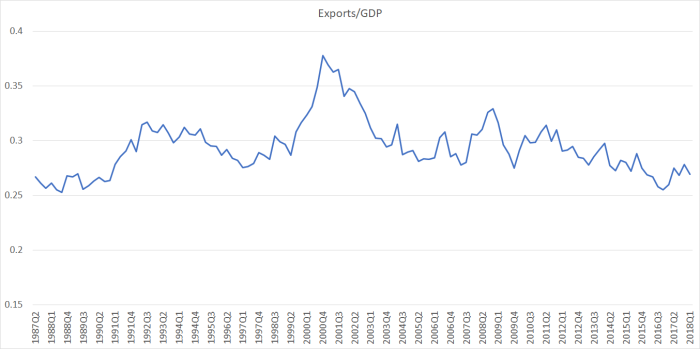

That means being smarter in how we work. It means an economy that produces and exports higher value goods, and one that makes sure that all New Zealanders share in the rewards of economic growth.

So what will we do?

First, we need a concerted effort to lift the prosperity side of the ledger. Working alongside business, we will encourage innovation, productivity and build a skilled workforce better equipped for the 21st century.

But what Our Plan has to offer is slim pickings indeed. The only specific is

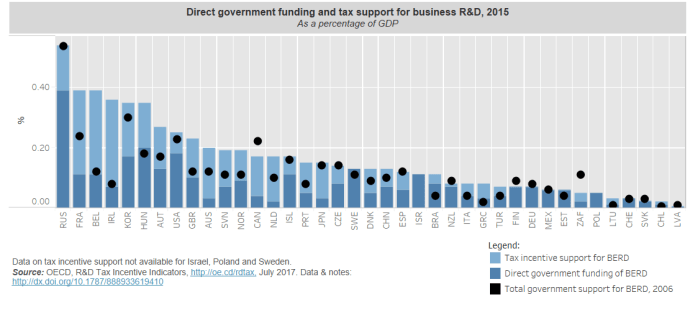

We are doing that by bringing back significant support for businesses to expand their investment in research and development through the R&D tax incentive, a key component of building a new innovative economy.

Perhaps you think R&D subsidies are a good idea. I’m rather more sceptical, and worry that there is no sign the government has thought hard about why firms don’t regard it as being in their interests to spend more here on R&D. But don’t just take it from me. I was interested that in the Secretary to the Treasury’s speech about productivity a couple of weeks back, which I wrote about here , there was no mention at all of R&D subsidies/credits as any part of the answer to our sustained underperformance. If R&D subsidies were the answer, it would have to be a pretty small question, and our economic underperformance is much worse than that.

It was also interesting that the tax system seemed to have disappeared from the list of answers to our economic underperformance. In the Speech from the Throne this

The government will review the tax system, looking at all options to improve its structure, fairness and balance, including better supporting regions and exporters, addressing the capital gain associated with property speculation and ensuring that multinationals contribute their share. Penalties for corporate fraud and tax evasion will increase.

and in various speeches since the Minister of Finance has continued to talk up tax system changes, but in Our Plan on Sunday the only reference I could see to the tax system was those R&D subsidies.

And then there was this

After all, we have always been inclined to do things differently. Or to do them first.

Whether it’s Kate Sheppard championing the right to vote, Michael Joseph Savage designing the welfare state, or Sir Edmund Hillary reaching brave new heights – we don’t mind if no one else has done something before we do.

But we do mind being left behind.

and

You asked us to make sure New Zealand wasn’t left behind.

But the problem is, Prime Minister, that we’ve fallen badly behind, and nothing you or your predecessors did seems to be stopping, let alone reversing that decline. Nothing.

Here are a couple of productivity charts, comparing New Zealand and some other advanced countries in 1970 (when the OECD data start) and 2016 (the last year the OECD has data for all countries).

First the G7 countries.

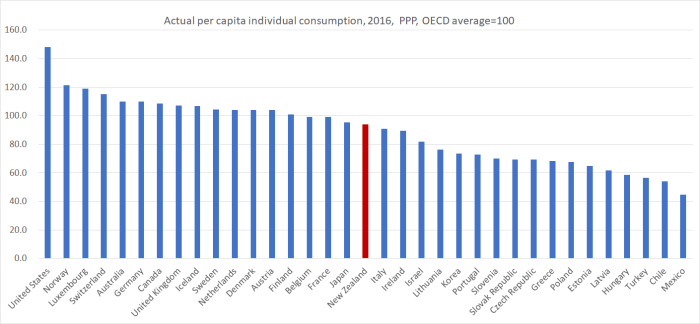

As recently as 1970, real GDP per hour worked in New Zealand was more or less that of the median G7 country (100 years ago, we would have been ahead of all but one, and basically level with the US). Now it would take a 30 per cent lift in New Zealand productivity – with no changes in the G7 countries – to get us back to parity with these big advanced economies.

And here is the same comparison for the (small) Nordic countries.

It would take a 50 per cent lift in New Zealand productivity – all else equal – to match the median of these countries. Even in 1970 we’d fallen behind them, but 100 years ago – in fact even when Michael Joseph Savage was in office – we were richer and more productive than all of them.

We’ve been left behind, and our politicians show no sign of doing anything to remedy the failure.

One could say much the same about housing. The Speech from the Throne – only 10 months ago – was actually quite encouraging. There were hints – nothing specific of course – that the government might actually want to lower the real prices of houses, reversing at least some of the disgraceful lift in house and land prices that policy (various strands interacting) has helped deliver over the last 25 years or so.

But what about in Our Plan? There is talk of warm dry homes, and of the Kiwibuild lottery for the lucky few (“I cannot tell you how exciting it was to open the ballot for those first homes this week”), but of the market generally only this

“But not everyone wants to own, or can right now.”

And nothing – at all – about what the government might do to systematically transform the outlook for those – all too many – who can’t. It might be terribly exciting for the Prime Minister that a few can win the lottery – as no doubt it is in the weekly Lotto draw – but in a serious government wouldn’t it be much more satisfying to have laid the ground work for systematic, across the board, affordability? In a country with so much land (in particular), it is pure political choice that we fail to have better outcomes.

There were a couple of other bits that took my eye. There was this, in prominent bold letters.

That’s why our first priority is to ensure that everyone who is able to, is either earning, learning, caring or volunteering.

Frankly, what business is it of the government’s. We aren’t resources at their disposal. Provided someone isn’t a financial burden on the state, why does the Prime Minister think it is for her to suggest – nay propose to “ensure” – that a life of leisure is not an option? The mindset is disconcerting to say the least.

And then there was the international dimension.

That brings me to our final priority area- creating an international reputation we can be proud of.

In this uncertain world, where long accepted positions have been met with fresh challenge – our response lies in the approach that we have historically taken. Speaking up for what we believe in, pitching in when our values are challenged and working tirelessly to draw in partners with shared views.

This Government’s view is that we can pursue this with more vigor – across the Pacific through the Pacific reset, in disarmament and in climate change, and in our defence of important institutions.

Ultimately though, my hope is that New Zealanders recognise themselves in the approach this Government takes.

I’d be ashamed if I recognised myself in the approach this government – and its predecessors – take. A government that is slow and reluctant to condemn Russia’s involvement in the Skripal poisoning, a government that appears to say nothing about the situation in Burma, a government that says not a word about the Saudi-led US-supported abuses in Yemen (trade deals to pursue I suppose). And then there is the People’s Republic of China.

The Prime Minister apparently won’t say a word (certainly not openly – and yet she talks about “transparent” government) about:

- the aggressive and illegal militarisation of the South China Sea,

- the growing military threat to Taiwan, a free and independent democracy,

- about the Xinjiang concentration camps, the similarly extreme measures used against Falun Gong, or the growing repression of Christian churches in China,

- about new PRC efforts to ensure that all Chinese corporates are treated, and operate, as agents of the state (is the Prime Minister going to do anything about Huawei for example?)

- about the activities of the PRC in attempting to subvert democracy and neutralise criticism in a growing list of countries.

And what is she going to do about the Belt and Road Initiative, which the previous government – in the specific form of Simon Bridges – signed onto last year, enthusing about a “fusion of civilisations”?

But then, why would we be surprised by this indifference. Her own party president, presumably with her imprimatur, praises Xi Jinping and the regime. Her predecessor, Phil Goff, had his mayoral campaign heavily funded by a large donation from donors in the PRC. And she won’t even criticise the fact that a former PRC intelligence official, a keen supporter of the PRC, sits in our Parliament, refusing to answer any substantive questions about his position.

If those are her values, they certainly aren’t mine. I hope they aren’t those of most New Zealanders.

If her “response lies in the approach that we have historically taken” it must seem pretty unrecognisable to the people, many on her side of politics, who protested French nuclear tests, or against apartheid in South Africa (and associated rugby tours). And would surely be unrecognisable to the ministers and Prime Ministers of that first Labour government, who were among those (internationally) most willing to take a stand against Italian and German aggression and repression in the 1930s.