In the run-up to the release this month of the new book by Julie Fry and Hayden Glass, which appears to focus on the potential for the immigration of highly-skilled people to contribute to lifting New Zealand’s long-term economic performance and the incomes of New Zealanders, I was doing a bit of reading around the issue.

At issue here is whether, or under what conditions, immigration to New Zealand of highly-skilled people can lift not only the average productivity of the workforce in New Zealand (that seems quite plausible in principle – think of a tech company simply relocating a particular research lab, staff and all, to New Zealand), but whether something about the skills those people have can translate into lifting the skills, productivity, and performance of the people who were already here. Those sorts of “spillovers” are really what we must be looking for if we are serious about running a skills-based immigration programme, as some sort of economic lever or, in the government’s words, a “critical economic enabler”. We can think about this in the context of New Zealand’s own history. European immigration to New Zealand in the 19th century brought people from the world’s (then) most advanced, innovative and economically successful society to a country where the indigenous population had been operating at a level not that much above subsistence. It would be astonishing if the European immigration had not raised average incomes of the people living in New Zealand (ie including the immigrants). But it would have been a pretty unsatisfactory programme if it had done nothing to lift the productivity, skills and income of the native New Zealanders.

Fry wrote an interesting working paper for the New Zealand Treasury a couple of years ago reviewing the arguments and evidence on the economic impact of (more recent) immigration to New Zealand. But when I went back and had a look at that paper I was a little surprised at how little focused discussion there was of mechanisms by which such productivity spillovers might occur – whether in generating more new ideas, or in applying better the stock of knowledge already extant – and how that might (or might not) have played out in New Zealand.

I also had a look at the old Department of Labour’s 2009 research synthesis on the economic impact of immigration. They had a nice discussion on the possible link between immigration and innovation. As they note, for some types of migrants to the United States there is reason to think that such spillovers might be material

The main mechanism in the United States appears to be the education of foreign graduate students rather than skilled worker immigration. The United States is the global leader in academic research, so the country attracts the top foreign students from across the world (positive self-selection). These account for most doctoral graduates (but there appears to be no crowding out of the United States born from research universities) and many of these foreign born doctoral students work in research and development (R&D) sectors in the United States, leading to a positive correlation between concentrations of highly skilled migrants and concentrations of patent activity.

Unfortunately, as they note, there is little evidence of such gains or spillovers in the limited New Zealand research. That might reflect the fact that our actual immigration programme has not been very highly skills oriented at all (something the data make pretty clear), which could perhaps be changed by altering the parameters of the immigration system. Or it might reflect some things about New Zealand that cannot easily be changed: we are small, and remote, relatively poor, and have universities which typically don’t rank highly as centres of research, in contrast to the United States which is not just the “global leader in academic research”, but large, wealthy and more centrally-located. And despite the recent surge in New Zealand exports of education services, that hasn’t been centred on our universities (it is a welcome boost to exports, but not likely to be the basis of any productivity spillovers to New Zealanders).

George Borjas is a leading US academic researcher on the economics of immigration and had a very accessible post up the other day looking at the question of productivity spillovers, and highlighting a range of quite recent and fascinating studies on some “natural experiments”. One of the cleanest such experiments was the purging by the Nazi regime in Germany of Jewish academics (and research students).

In 1933, shortly after it took power, the Nazi regime passed the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service, which mandated that all civil servants who were not of Aryan descent be immediately dismissed. That meant that Jewish professors like John von Neumann, Richard Courant, and Albert Einstein were fired from their university posts. Many of these stellar scientists found jobs abroad, particularly in the United States.

Researchers have been looking at what the impact of these dismissals, and relocations, was on the productivity of those around them. That included the impact on the productivity (published research output) of the graduate students (PhD candidates) of those the dismissed academics had been working with, the impact on the output of former colleagues of those who had been dismissed, and the impact on the colleagues that dismissed academics found themselves working with later (in the case of those who subsequently took up US academic positions).

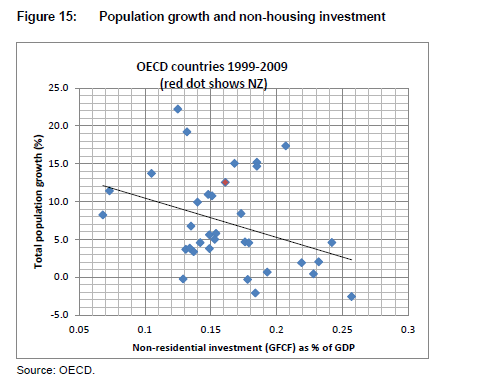

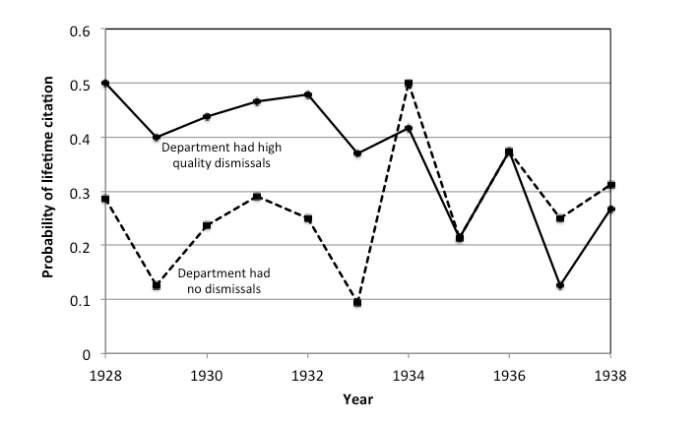

This is perhaps the starkest chart from Borgas’s post, drawn from this paper, illustrating the lifetime impact on the graduate students left behind.

There are clear signs of a material adverse long-term impact (the mirror image of the sort of positive productivity spillovers those promoting a high-skills immigration programme are looking for). PhD programme supervisors can matter hugely. But any impact on the productivity of former colleagues was much less visible.

In another paper, recently published in the AER, looking at the impact on innovation in the US from the relocation of these displaced Jewish scientists, the authors find that the new recruits did not increase the productivity of existing US inventors, but encouraged greater innovation in the US as a whole by attracting new researchers to their distinctive sub-fields of research.

Borgas sums up his take on this series of papers thus

My take from all this is very simple: At least in the experimental context, the evidence that high-skill immigrants produce beneficial spillovers is most convincing when the immigrants that make up the supply shock are really, really high-skill; when the number of such exceptional immigrants is sufficiently small relative to the market; and when those immigrants directly interact with the potential recipients of the spillovers.

Or as he put it in another of his own recent journal articles looking at the impact of the mass emigration of Soviet mathematicians following the fall of the Soviet Union

Knowledge spillovers, in effect, are like halos over the heads of the highest-quality knowledge producers, reflecting only on those who work directly with the stars

I found these papers fascinating in their own right (nerd that I am) but they also prompt thought about what we can actually hope for in a New Zealand context. Even if we get past the sick-joke aspect of New Zealand’s allegedly skills-based immigration, and the disproportionate number of chefs, aged care nurses, and café and shop managers, what could we really expect to be able to achieve with the best possible skills-based programme?

It would almost certainly be a much smaller programme. And it would have to aggressively target the very best people – not be content with people who just happen to creep above a points-threshold, artificially boosted by a willingness to move to some of the more remote and less economically promising parts of the country.

But then one has to ask how realistic any of this is. With all due respect to our green and pleasant, and moderately prosperous, land, why would the very best people want to come to New Zealand, let alone stay here? We had our own stellar academic refuge from the Nazis – Karl Popper taught at Canterbury for several years – but even he didn’t stay that long. We have adequate, but not great, universities – and there are many better in countries with many of the good things New Zealand can offer. We have modest academic salaries. We have small home markets, small networks of people working in possible similar areas, and if global markets in principle can be serviced from anywhere, evidence still suggests people tend to do it from closer rather than further away. We seem to have almost nothing of what 1930s Britain or the US could offer to the displaced German academics – or certainly nothing that a wide range of other countries couldn’t offer more of, more remuneratively.

But perhaps Fry and Glass can make a robust and more optimistic case. I’ll look forward to the book, and will no doubt write about it here.