Last week, The Treasury hosted a guest lecture featuring two visiting academics under the heading Brexit, Trump & Economics: Where did we go wrong. One of the visitors – Samuel Bowles, now a professor at the Santa Fe Insitute -had been around long enough that in his youth he had served as an economic adviser in Robert Kennedy’s presidential campaign, and at other times as an economic adviser to the Castro government in Cuba. The other – Wendy Carlin – is a professor of economics at University College, London.

When the invitation went out, I was rather puzzled by the title? Who was this “we” that apparently “got things wrong”? After all, I was – and remain – keen on Brexit, and will recall for a long time the thrill of that June Friday afternoon as the results rolled in. And if I wasn’t a Trump supporter, I wasn’t a Clinton one either. There is a fascinating question as to how Trump became the Republican nominee, but once that had happened one of two unattractive candidates was going to become president.

“We” turned out to be economists. And by getting things wrong, Bowles and Carlin didn’t mean simply getting eve-of-polling-day forecasts wrong (after all, that late in the day even some pretty prominent Leave figures didn’t expect to win). Instead, economists were held to blame for these otherwise unthinkable, apparently lamentable, events occurring in the first place. If only economists had done a better job, the deplorable events would never have happened. Or so the story went. The tone was one that surely no right-thinking person could have wanted such outcomes (Brexit was even described as a “gloomy event”). As this was the second Treasury guest lecture in recent months deploring Brexit, I start to wonder if the organisation now has a quasi-official view (or perhaps it is just the British CEO)?

I’m still not entirely persuaded that either event – Brexit or Trump – is quite as earthshattering as the liberal elite seem to make out, or even that they are very closely connected. UK voters chose to leave the EU by a margin of 52:48. That is a large enough margin not to require recounts, but hardly an overwhelming margin. And the same voters only a year early had re-elected (this time with an absolute majority) David Cameron and Conservative Party, on a not-remotely-radical platform. And today, Cameron and Osborne are gone, and Britain still has a not-remotely-radical (perhaps only slightly more reforming than John Key) Conservative government, with a massive lead in the polls – albeit, the latter is as much about the problems with the Labour Party as anything else. The government is charged with implementing Brexit, and there seems to be not the slightest sign of some turn inwards, or reversion to protectionism, on goods and capital flows.

Of course, if your vision was one of ever-closer-union, and a mental model in which there was only a one-way door to the EU, perhaps it is a great shock. After all, if Brexit works more less okay, it might suggest to other countries’ citizens that there are reasonable alternatives to being part of the EU. And that simply isn’t so radical – after all, most of the world’s people show no interest in becoming citizens of multi-national superstates. And the tendency of the last 100 years has been towards more sovereign states not fewer. Lower barriers to international trade help make that possibility more economically viable.

And it is not as if the public in the United Kingdom has ever been very enthusiastic about subsuming sovereignty into some quasi-democratic entity based in Brussels. The technocratic elites may have been enthusiastic, but the public seem never to seen anything very wrong about being British. When your country has been free, and on the right side of the major conflicts of the last 100 years, it is hardly a surprising stance. Citizens of Spain or Austria might see things differently.

I wrote a post earlier in the year about the fascinating polling data from the early 1970s I stumbled across in a book reviewing UK entry to the EU in 1973. For all the talk that it was poorer, unskilled, older people who voted to Leave – as if somehow that changes the character of the decisions – in the early 1970s, when overall opinion was pretty closely divided on entering the EU, it was those same groups who opposed joining. And of course the same people who were young in 1972, are old in 2016. As I noted in that earlier post, what was striking from the polling data (comparing the early 1970s and the 2016 exit polls), is the change in attitudes among the more highly educated groups. Among the AB group (professional and managerial occupations), in the early 1970s there was a huge margin (50 percentage points) in favour of joining the EU. In the 2016 exit polls, there was a margin of only 14 percentage points (57:43) in favour of remaining in the EU. Poor and unskilled changed their minds (as a cohort) less than did the more highly educated groups – and those more highly educated groups became much more opposed to staying in the EU.

But for Bowles and Carlin, economists had failed the world. They presented familiar data showing that most economists thought that Brexit would come at some economic cost (and of course, the great and the good – the OECD, the IMF, the Bank of England, and the UK Treasury shared that view). And yet the voters had the temerity to ignore these experts. When I pushed them on the point, they did – somewhat reluctantly – accept that it wasn’t necessarily unreasonable for voters to make decisions on grounds other than economic ones (as I noted, most colonial independence movements – even the Irish one – probably came at an economic cost). But it was a reluctant concession – these were people who could really only see one end in view, less national sovereignty, more global rulemaking, and they could only lament the choices of British voters – blaming economists for championing policies which had “made the backlash inevitable”.

(The second half the guest lecture was a presentation about a new approach to teaching introductory economics. It looked quite promising, but the connection between a possible better approach to teaching basic economics and voters in future “being more willing to take advice from economists” seemed tenuous at best.)

As for the Trump phenomenon, I’m also not sure quite how big an event that should be seen as. The last count I saw gave Hillary Clinton 48.2 per cent of the popular vote, and Trump 46.3 per cent. Four years ago, the Democratic candidate scored 51.1 per cent of the popular vote, and the Republican candidate 47.2 per cent. Presidential elections aren’t decided by national popular vote totals (any more than, say, UK parliamentary elections are) but these aren’t big shifts in the overall vote share. Yes, the presidency changes hands – as it was going to do anyway – but a few hundred thousand votes in a few key states and things could easily have been different. Are economists really to blame for the fact that the Democratic Party chose such a weak candidate – who largely ignored many of those tight rust-belt states, despite the advice of her own husband? And whoever is to blame for Wikileaks I doubt it is the economics profession?

In 1984 Ronald Reagan took 58.8 per cent of the popular vote, in 1972, Richard Nixon took 60.7 per cent, in 1964 Lyndon Johnson took 61.0 per cent and in 1956 Dwight Eisenhower took 57.4 per cent. Those were landslides (in a New Zealand context, electoral landslides – 1972, 1975, and 1990 involved perhaps seven percentage point gaps in overall vote shares). This was a very tight election, fought between two deeply flawed candidates. And if Trump’s success may have helped some Republicans in the House and Senate, very few were campaigning on some Trumpesque policy ticket – whatever the specifics of such a ticket might actually have looked like. Like them or not, the appointees to the Trump cabinet announced so far, don’t seem a million miles from many of the sort of people who might well have been appointed to serve in any Republican president’s cabinet. And being a democracy, parties tend to alternate in office.

What was pretty clear as the Treasury guest lecture went on was that the speakers were mostly just pushing a social liberal ideological agenda (as they characterised their concern it was about a “a revolt against liberal tolerance”. Things were wrong when their side didn’t win and somehow – weirdly – economists were to blame. That isn’t just my interpretation of the event – it was a proposition put to them at the lecture by Professor Jonathan Boston, himself proudly socially liberal. What wasn’t clear was why our Treasury was aiding and abetting their cause. (Or for that matter, how the ascendancy – voted in by US voters, well aware of most of his flaws – of such a symbol of the decadence of modern culture as Trump even represents a defeat for the social liberal project.)

In passing, there was one truly fascinating snippet in the lecture. Bowles is adamant that a much higher level of economic equality is “not hard to create” – and he treats such outcomes as highly desirable. According to his research, the level of economic inequality in modern Denmark and Sweden is about the same as that found in ancient hunter-gatherer societies. It was almost worth venturing into town for the afternoon just for that.

In the same vein, I came across an interesting report from a conference held in the UK last month under the title “Brexit and the economics of populism”. The conference was attended by a cast of 50 or so academics, journalists, and some leading market economists from across Europe. There were some very able participants and it looks to have been a fascinating day’s discussion. The 12 page conference report is well worth reading for anyone with an interest in Brexit, Trump, modern macro and micro policymaking – and in the attitudes of the (non-political in this case) elites.

What was perhaps striking – and this is the real link to the Bowles/Carlin lecture here last week – is that there is no sign in the entire report that anyone who spoke had themselves been a Brexit supporter (even though 43 per cent of the ABs had favoured Brexit). The report captures one questioner noting that it is not unreasonable for people to vote on non-economic grounds, and that is about it. And the report is full of references to those ill-defined and pejorative phrases “populism”, “xenophobia”, “nativism” and – heaven forbid – “nationalism”. I had to look up “nativism” – it isn’t a term that pops up much in New Zealand debates. According to Wikipedia

Nativism is the political position of supporting a favored status for certain established inhabitants of a nation (i.e. self-identified citizens) as compared to claims of newcomers or immigrants

One might play around at the margins with the precise wording, but it looks like a definition that probably describes the overwhelming bulk of voters. And there will be few elected politicians (ie people who have actually persuaded people to vote for them) who seriously think that the interests of foreigners rank equally with the interests of citizens.

Next thing people will be having a go at “familism” – the belief that the interests of one’s own family might rank more highly in one’s own concerns than those of other people’s families, domestic or foreign.

The conference report suggests participants thought governments needed to do better. And, of course, there are areas in which that is no doubt true. Often enough, that might involve avoiding hubristic schemes – like the euro, or the EU on current scale – in the first place. Or respecting the principle of subsidiarity – pushing decisions back to national governments (and perhaps even lower levels of government) whenever possible. And respecting public preferences and choices. And acknowledging the sheer limitations of the knowledge of experts in so many areas – including economics.

But that wasn’t the focus of the attendees at this conference. Instead, it was a recipe that seemed to have three broad dimensions:

- a more active role for government, in particular in discretionary fiscal policy (as if debt levels in many of these countries were not already uncomfortably high),

- putting more decisions at an arms-length from elected politicians (whether delegating more fiscal policy to independent agencies, or promoting international regulatory alignment), and

- convincing the public that there really were significant benefits from large scale immigration.

In fairness, there was some recognition that dysfunctional housing markets are a major problem, but no speaker or questioner is reported as having favoured extensive land use liberalisation. Instead, more roles for active government were in view.

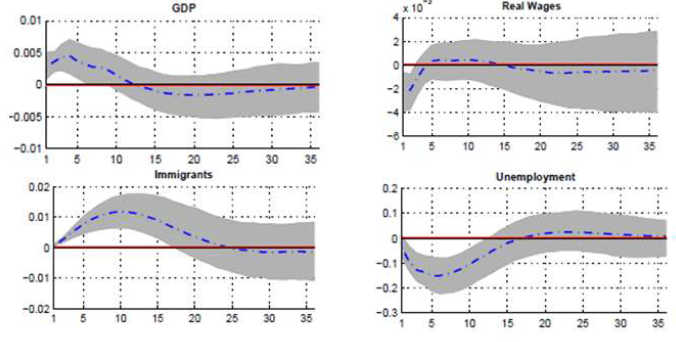

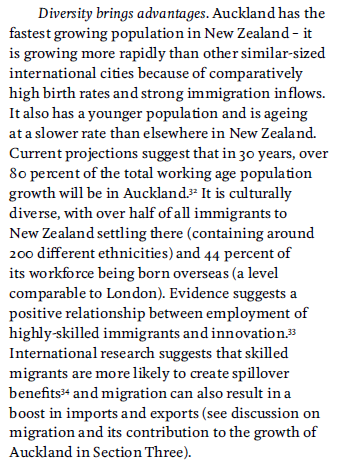

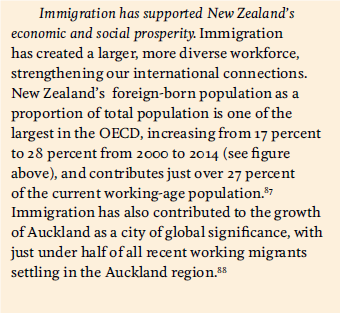

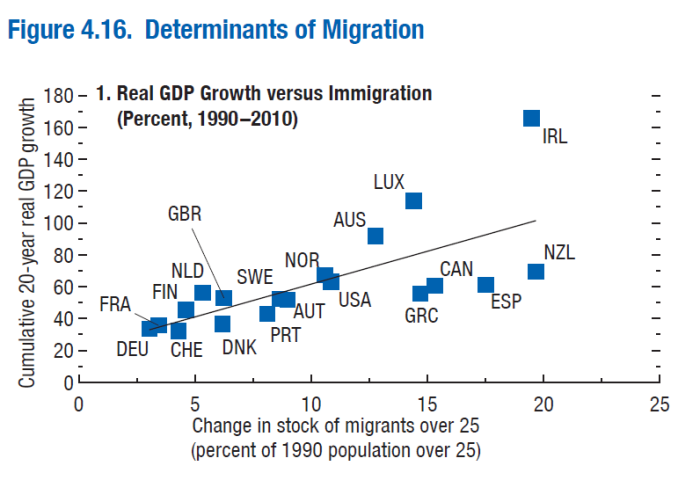

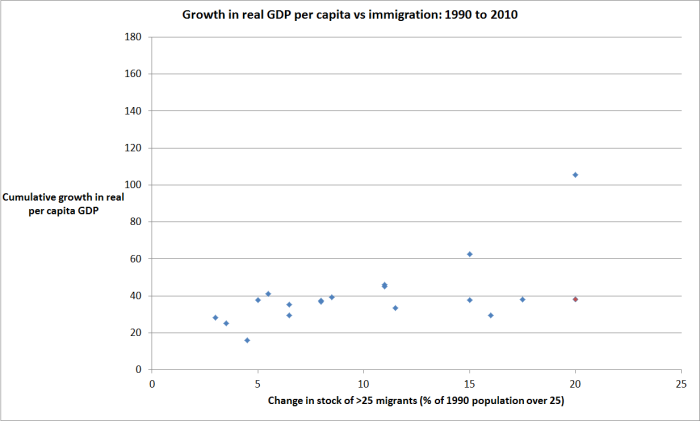

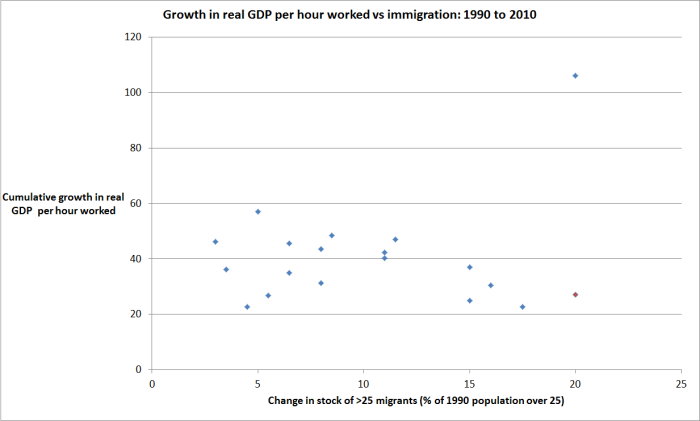

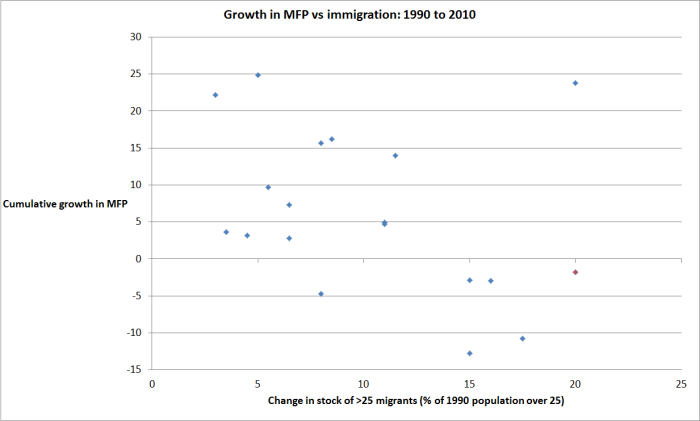

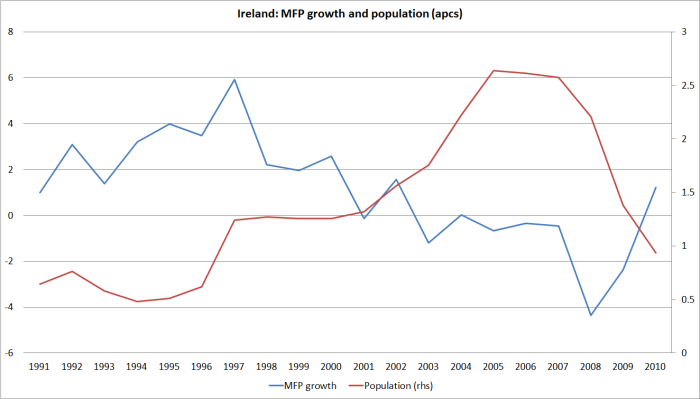

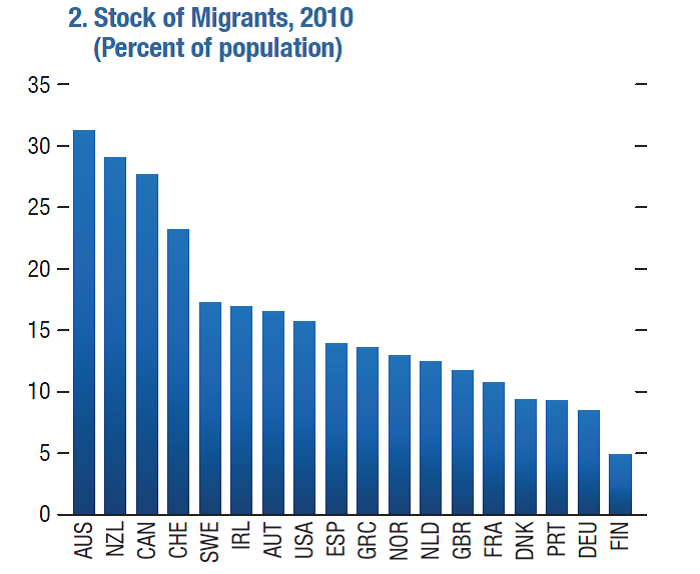

The immigration stance, of course, caught my eye. As the report writer noted there is an “academic consensus that wealthy countries benefit from migration from developing to developed countries”, but most of the comment was devoted to trying to play down the potential costs to relatively unskilled native workers. I’m sure these people are quite sincere in their beliefs that there are benefits to advanced countries (and their existing citizens?) but I can’t help thinking that if the gains were that real, and it were that important an issue, the advocates would find it much easier to demonstrate the benefits (to the rest of us) than they do. Perhaps quite often large scale immigration doesn’t do much harm to natives, but there isn’t much sign that does much good either. In fact, support for large scale immigration – whether in Europe or Australasia – is often more of an ideological proposition than one grounded in robust evidence. It seems as much about a desire to change a society – in ways which natives often don’t want – than to lift overall economic prosperity for citizens. (But in defence of the Europeans, at least no one in this conference is reported as advocating for immigration on the specious grounds – invoked often by our business leaders and the incoming Minister of Finance – that immigration is needed to fill “skill shortages”.)

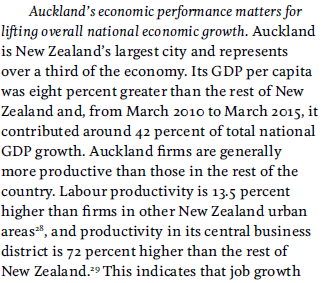

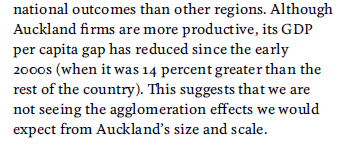

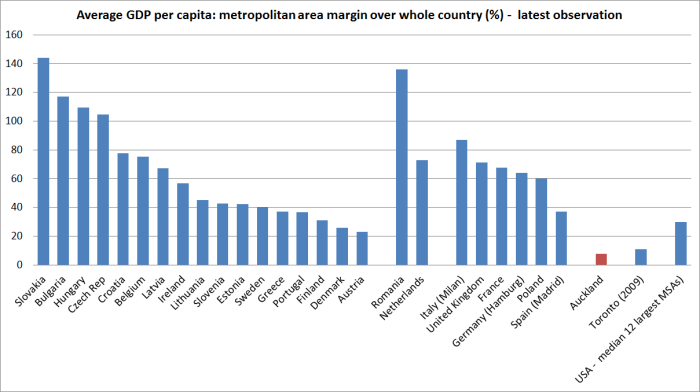

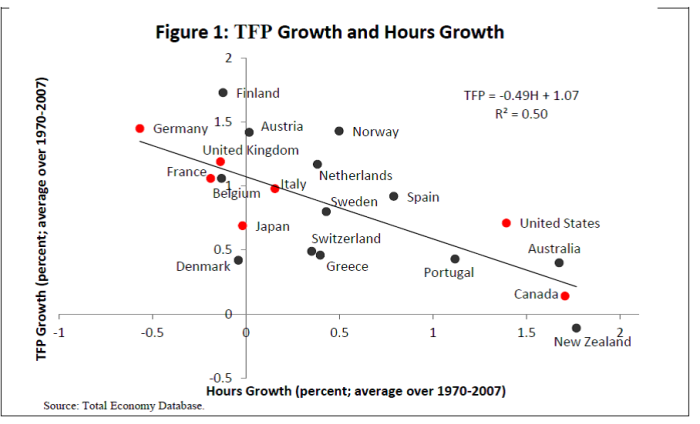

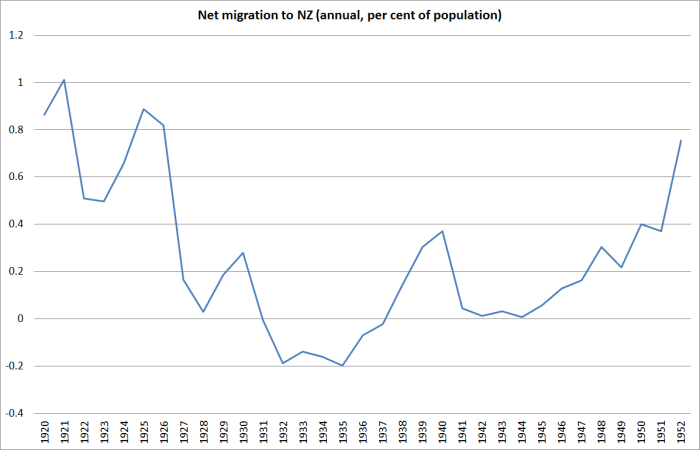

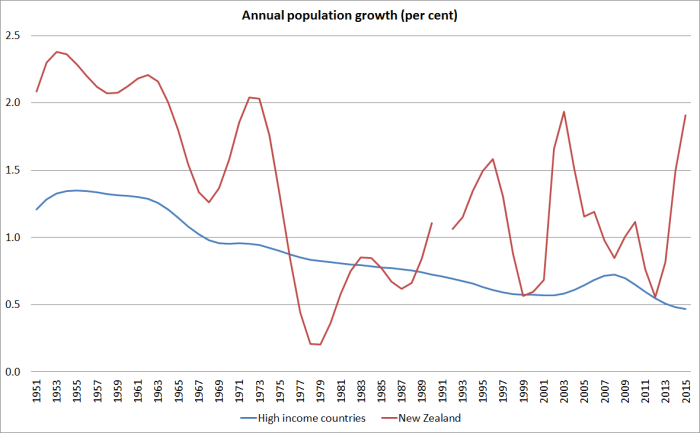

If you got this far, you might be wondering what the point of this post was. I feel somewhat that way myself. But it was partly about getting a few things off my chest, partly about passing along the link to the interesting conference report, and partly about thinking through my reaction to those who ominously go “could it – Trump, Brexit – happen here?” Could what? A couple of close votes – one of which leaves in place a very moderate centre-right government, and the other of which installs a President who seems to have very few fixed views. In the specific sense, clearly not. We aren’t part of some multi-national entity like the EU, and our electoral system is very different from that of the US. Then again, perhaps there could be a revolt against decades of economic underperformance, decades of elite indifference to that underperformance, and an extraordinarily high target rate of immigration which changes the character of the country without doing anything apparent to improve its economic performance. It could happen, but frankly it doesn’t seem very likely right now. Easier just to keep on pretending everything is fine.