I’ve written a few posts here over the years about the idea – which apparently Labour, National, and the Greens are now keen on – of a state established and funded policy costings unit. The most recent two were a month ago, here and here. I’m a longstanding sceptic of the case for such a unit, seeing it is just a way to get more state funding for political parties, and not dealing with any of the common arguments made for such units.

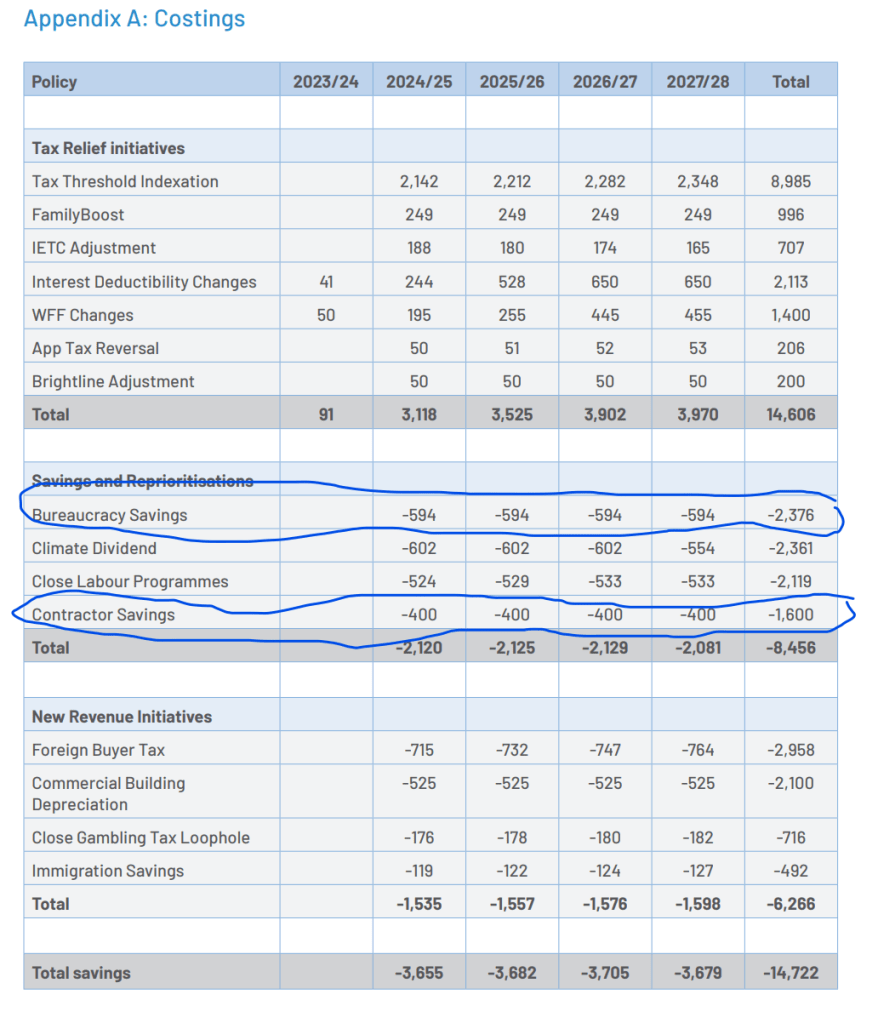

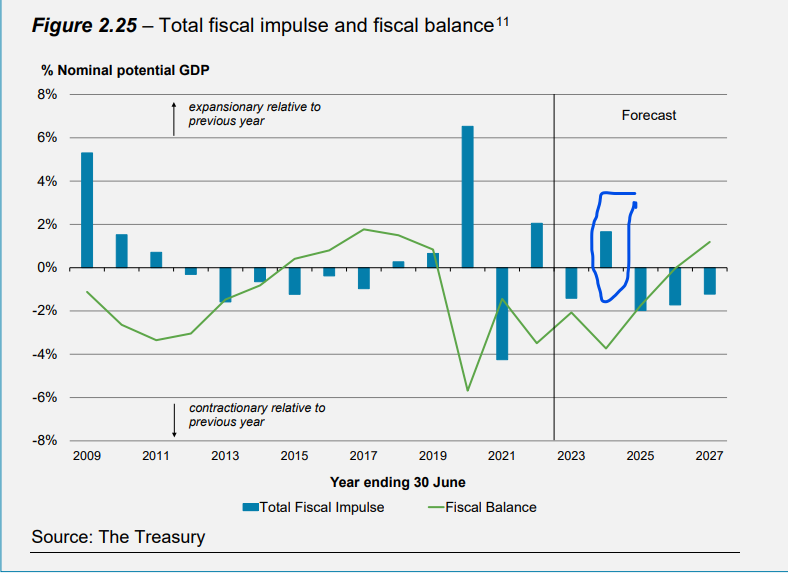

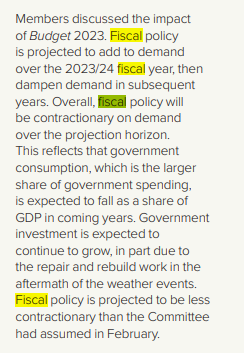

It is election season now and some of the arguments have, in effect, been put to the test. This week National released its tax and spending plan, producing numbers suggesting that what they planned to spend was fully funded by other cuts and new taxes. I wrote here about the macro issues and implications of/around the plan, largely taking as given the specific numbers the party supplied.

I’m not close enough to any of the line by line numbers to know whether each of them is solidly costed. Their economic consultants say they have been, and (assuming there were no silly mistakes made by accident) National does have a pretty strong incentive to ensure the numbers are each reasonably robust. So, for now, I’ll assume they are (with a few possible caveats about the foreign buyers tax, see below).

[and, later, on that tax]

…As for the revenue estimates ($750 million a year), they seem quite high, and the tax rate seems high by most international standards (Singapore is a lot higher). Only time will tell how many people not living here so want a New Zealand house they will pay a 15 per cent tax to do so.

Individual costings really weren’t and, as macroeconomic commentator, still aren’t my focus. In the grand scheme of things, the overall package involves adjustments of less than 1 per cent of GDP per annum, most costings don’t seem to have been contested, and in an age of MMP even a big party’s plans are likely to be implemented a bit differently than the pre-election promises. The foreign property buyers tax itself is expected to raise revenue equal to 0.2 per cent of annual GDP (and the gambling tax about 0.05 per cent of annual GDP).

But both as a potential voter and as someone interested in institutional proposals, notably that for policy costings offices, the subsequent debate has been interesting. I don’t really understand the issues around the online gambling costings (and the amounts involved are much smaller) so I’m going to focus on the foreign buyer tax. On that score there seem to be two quite separable concerns raised:

- first, how consistent is the proposed tax with various tax and trade treaties New Zealand has signed? and

- second, even if the tax were able to be put into effect as National tells us it envisages it (excluding buyers from Australia and Singapore, as with the current outright ban), just how much revenue would the tax be likely to raise year in year out?

Of course, the more there are issues under the first leg, the more questions could legitimately be raised about the revenue estimates.

Based on what they have told us, in the lead up to the announcement National did what one might have expected from a party seeking to win the right to lead the government after the election. It hired a firm of advisers (Castalia) and asked them to review the draft numbers. From what National has said (and I recall one media outlet being shown Castalia’s comments), National went with numbers that were generally at the conservative and cautious end of the spectrum. Castalia apparently also cast a fresh eye over the numbers in light of the government’s fiscal announcements last Monday (although this is unlikely to have meant much since how much baseline spending can be saved – by either party – isn’t really something a consultant can tell you, since it is mostly about the resolve of the politicians’ themselves once in office).

In addition to having consultants review modelling numbers, the National document told us they’d sought legal advice

National has sought legal advice on whether the replacement of the foreign buyer ban with a foreign buyer tax is consistent with New Zealand’s existing free trade agreements – that advice confirms such a replacement would be consistent with those agreements. However, this policy assumes Australian and Singaporean citizens will not be affected by the tax as they are not currently affected by the foreign buyer ban.

and a Newshub article yesterday reported that National had sought both legal and tax advice on these issues.

So far and mostly so good. We don’t just have National’s word for the numbers, but an established firm – yes, paid for by National, but with an ongoing reputation to guard – is reported as telling us they thought the numbers overall had been cautious and conservative.

But then the questions arose. First, around the legality of imposing such a tax on various countries. Some of the points were from Labour Party spokespeople (eg this press statement). They are the political opposition so we might have no more particular reason to take their claims on trust than to take National’s on trust, but they do make some specific points, which to a lay voter seem like questions deserving an answer. In fact, there might be both legal questions and questions about whether the proposed tax is within the spirit of agreements that New Zealand governments have voluntarily entered into (and which National is not on record as having opposed, or is now proposing to withdraw from). (Non-specialists among us might also wonder why if absolute bans – the ultimate in discrimination – mostly are legally okay (we now have one), a tax which would be less onerous would not.) As National notes, some other jurisdictions have such taxes, but the issues here isn’t one of merits, but what specific New Zealand agreements do and don’t allow (and noting that New South Wales appears to have recently withdrawn its version of such a tax because of federal tax treaty issues).

And then questions arose around the modelling (ie even if the law could be done as National had suggested whether it would raise $750 million or so year in year out). Various economists and property analysts (people without apparent strong party loyalties that might make their perspectives suspect) raised doubts. On the property experts side this article from today’s Post seems representative.

There are, of course, some enthusiastic real estate agents. I read an article reporting one agent saying he’d had US billionaire clients on the phone within hours. I don’t doubt there would be interest: the question is how much, and how much beyond the first wave (a quick Google suggests there only 2700 billionaires in the world).

Without seeing National’s modelling, it isn’t really possible to reach a confident view on their numbers. But what makes me cautious is that I’ve seen no one – neutral expert or even National surrogate arguing that the numbers are really on the cautious side and a more realistic assessment might be higher again. It seems hard to find revenue estimates for other countries’ foreign buyer taxes – often they are designed to deter purchases rather than to raise revenue – although I found a reference yesterday suggesting that a similar tax in Toronto (a metropolitan area with more people than New Zealand) was raising only about $200m per annum.

So wouldn’t this have been a clear case for a policy costings office? I don’t think so.

National has used its (scarce) resources to pay for analysis and advice and has told as much as it seems to want to tell us. Debate and scrutiny has ensued. As a geeky analyst and undecided potential voter I’d really like them to release their modelling and any Castalia comments on it, and either the advice or a fairly full summary of the advice from the “legal and tax experts”. It would be good even if they had some known National-sympathising experts who they could wheel out to make the case for (a) the legal problems not being what some suggest they might be, and b) the robustness of the numbers (I don’t really expect Willis or their Revenue spokesperson to spending lots of time in public debate in the middle of a campaign).

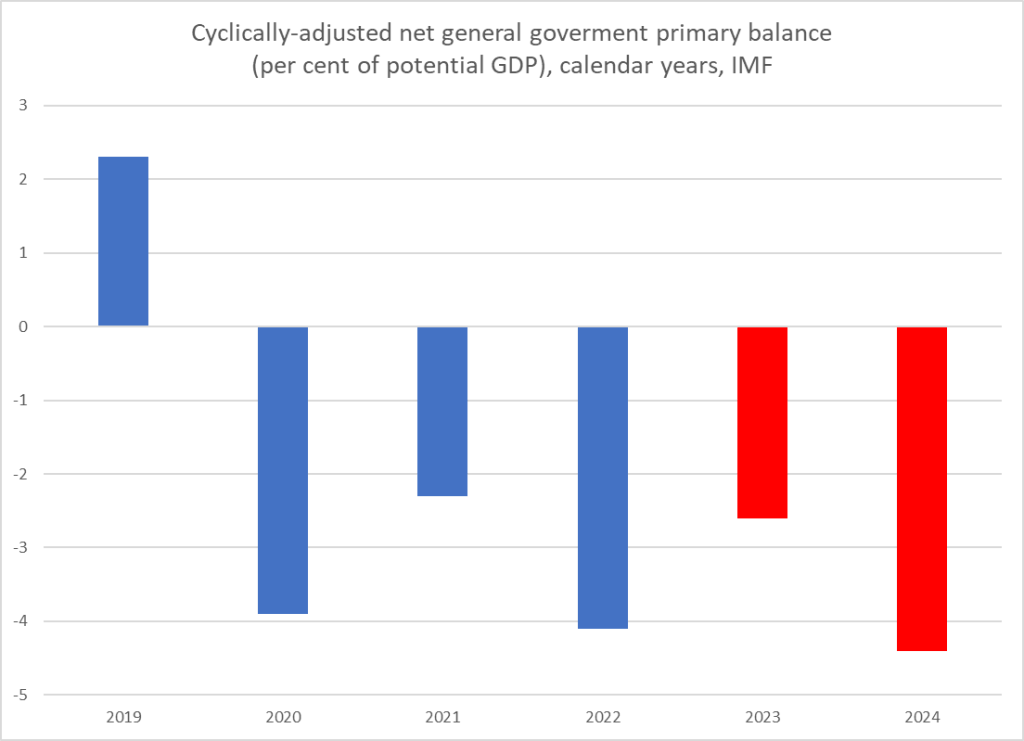

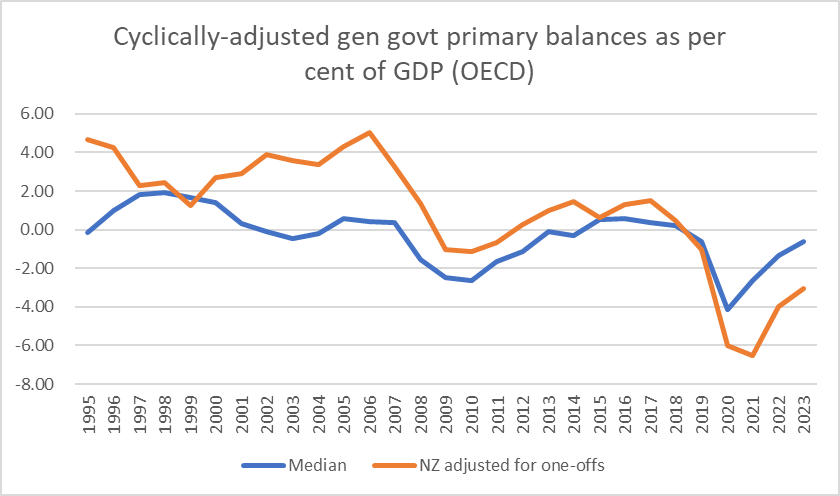

But here’s the thing. It is their choice what to release (or not), and our choice as voters to draw our own conclusions. Elections are most unlikely to turn on a specific like this, which is ultimately fairly small in the scheme of things (eg against the backdrop of some of the largest primary fiscal deficits of any advanced country at present, 0.2 per cent of revenue isn’t nothing but it is almost lost in the rounding – and is less than the non-specific proposed bureaucracy savings). For some people and at the margin, it may shake confidence. Go back to that quote from my post earlier in the week: my starting point was to think that National had strong incentives to make sure that their numbers were robust, so as a starting point I took them as given. Now that questions (apparently serious questions) having been raised, they have chosen not to release anything more or to address the specific concerns. It is a legitimate choice (they are free to make it), but I (and the handful of interested analysts and potential voters) can draw my own conclusions. For me, I’m less confident now that the numbers add up, and also less confident than I might have hoped in their commitment towards being an open and transparent party in government. It reinforces my wider doubts about their overall fiscal stance.

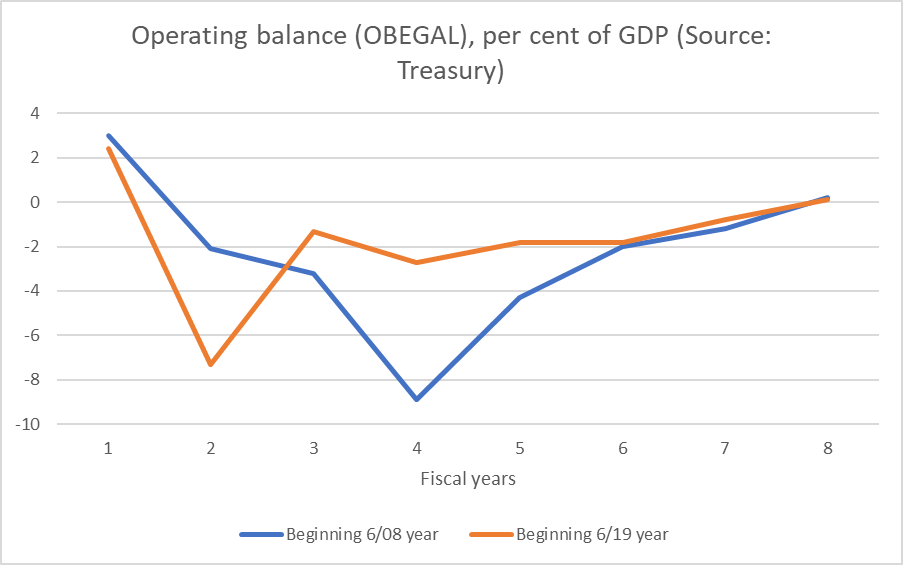

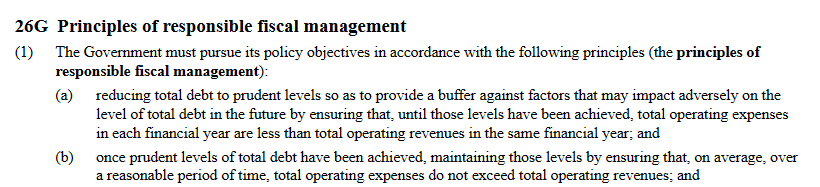

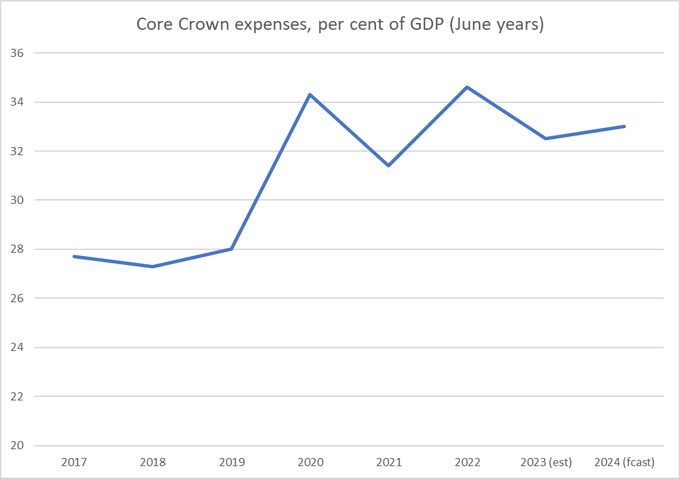

And that seems to be the political market working. Parties will make choices about what they think a sufficient number of voters care about, or even about what sufficiently vocal commentators might shape public thinking over. It is very unlikely that details of this tax score highly on either count. Is that a bad thing? I don’t really think so. Voters are making judgements about values, about competence, about desires (or lack of them) for change. And frankly, if fiscal issues were to become an issue, such concerns should probably centre on things individually more important than details of this tax. The merits of unprincipled tax policies (this foreign buyers’ tax, Labour’s proposed GST exemptions, or the distortionary new depreciation provisions both parties have individually proposed to foist on the business sector) for example should probably count for more. Or the sheer size of deficits – without precedent in New Zealand now for many decades on the eve of an election. But in the end, voters and parties will make their own choices, and nothing this week suggests to me that we’d have been better with some state-funded tax and trade lawyers and economist adding to the mix. Precise numbers almost certainly do, and in my view probably should, matter less than what we learn about parties and their spokespeople in how they handle issues like this.