(This is a long post. The Executive Summary is that there was a bar on any active or future researcher on macro or monetary issues serving on the Reserve Bank MPC when it was established. Everyone accepted that this was so, and both the Minister and the Bank had defended the bar. Recently, the Reserve Bank Board chair Neil Quigley persuaded Treasury to state publicly that it had all been a misunderstanding and there had never been such a ban. None of the extensive documentation supports Quigley’s belated claims or explains Treasury’s willingness to champion his rewrite of history.)

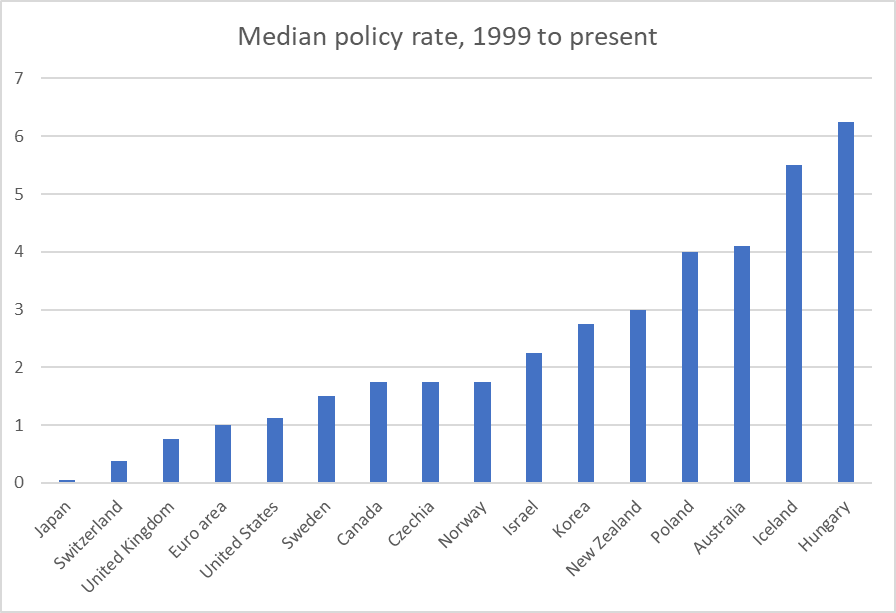

About six weeks ago the ban that had been placed on anyone with current or likely future research expertise or interest in macroeconomics and monetary policy serving as external members on the Monetary Policy Committee was once again in the headlines. The Reserve Bank Board had just advertised to fill the two vacancies that will arise next year (yes, you might wonder why they were advertising now when it isn’t clear who will form the next government or what their expectations for the Reserve Bank might be, but leave that for another day). In the advertisement it was pretty clear that the former ban had now been lifted. If so, that was a really welcome step forward. The proof would still be in the sort of appointments eventually made, and the strong suspicion is that the more important (but unwritten) blackball is still in place – no one seriously likely to challenge the Governor or known for thinking independently was likely to be appointed. But it was a start. And would at least mean the Board and Minister were no longer open to the charge of having the only central bank in the advanced world (or most of the rest) where relevant expertise was a formal disqualifying factor from membership of a monetary policy decision making body. The list of former leading central bank figures internationally who would have been disqualified under such a rule is very long indeed.

I idly wondered what had led to the change.

The Herald’s Jenée Tibshraeny has done sterling work in giving this issue some of the coverage it deserved (where, one often wondered, were the Opposition parties), initially at interest.co.nz and now at the Herald. She asked what had gone on and got a surprising answer from The Treasury and the Minister of Finance. It had all, we were asked to believe, been a misunderstanding, and there never was such a restriction. Tibshraeny’s 21 June story is here. I wrote about the story, documenting how improbable these revisionist claims were, here. And then I lodged an OIA request with The Treasury.

To step back for a moment, the existence of this restriction was first confirmed in a response to an OIA I lodged with the Minister of Finance after the first MPC appointments were made in March 2019. The Minister’s response is here. A short Treasury report to the Minister, dated 29 January 2019 and signed out by the Manager, Governance and Appointments contained the following paragraph on the first (of two) pages (it was a covering memo relating to getting the Minister to send a paper to Cabinet’s Appointments and Honours Committee to make the MPC appointments)

It didn’t leave much room for doubt, and came as no surprise to me because what was written there was what I had been told some months earlier by a well-qualified academic who’d expressed interest in the possibility of an MPC role. Here is how I described in a post when the papers were first released by Robertson

I couldn’t use that information when the person first told me – and had to wonder if somehow they’d got the wrong end of the stick- but it informed the framing of my OIA. The person concerned was told of this bar as it applied to people like him by both the recruitment consultants the Board was using and by the Board chair himself.

Tibshraeny gave the issue coverage. Here was her 1 August 2019 story. There were scathing comments from former Reserve Bank Governor Don Brash, critical comments from Eric Crampton (and some of my post’s critical lines), as well as some comments from former Reserve Bank Governor Alan Bollard suggesting that perhaps all that had really been meant was not having people with “market interests”. But what really mattered were comments from the Minister of Finance himself and an official “Reserve Bank spokesperson”.

Here was Robertson

which sounds defensive and unenthusiastic, but certainly not suggesting that there was not a restriction, let alone suggesting that a Treasury official had simply made a mistake in that January 2019 report.

And from the Bank’s side

To the first paragraph one goes “of course” (as in, we don’t want MPC members also selling their wares to hedge funds etc at the same time), the second para is beside the point (the issue with the blackball was about research), and as for the third……..doesn’t that first phrase (“looser criteria…..”) read almost exactly like the words of the initial Treasury report. There was no suggestion at all that some Treasury official had just got the wrong end of the stick. Rather, as was their right (and job), they defended the stance that had apparently been adopted by the Board and the Minister. And while it was an anonymous spokesperson, there is absolutely no way those lines would not have been cleared with the Governor, and probably cleared with – but certainly advised to – the chair of the Board, Neil Quigley. Had Quigley then thought the Treasury report had misrepresented him or his Board, it would have been easy to have issued a clarifying statement.

And there the issue lay for a couple of years – there were no external MPC vacancies, and Covid overran everything. But in early 2022 the first terms of two MPC members were coming to an end. And in the margins questions were getting raised as to whether the blackball restriction was still going to be in place. Tibshraeny – who had talked to at least a couple of us – was on the ball again and went and asked both the Minister and the Bank about the specific restriction. Her story appeared on 19 February 2022.

There are no quotes from either Robertson or the Bank (presumably she just got responses along the lines of “no, there has been no change” rather than anything more enlightening).

Tibshraeny went further, seeking comment from others. This time she sought comment first from John McDermott former Chief Economist and Assistant Governor at the Reserve Bank.

And he wasn’t just speculating about the nature of restrictions. He had still been Chief Economist and Assistant Governor in the second half of 2018 when these policies and restrictions were being formulated, and is an active participant in email exchanges among RB senior managers on the sort of people who might be appointed (that were contained in the Reserve Bank’s OIA release to me in 2019 around MPC appointments). He disagrees with the blackball restrictions, but doesn’t suggest anyone misunderstood, because he will have known that it did represent the agreed stance of the Board and the Minister.

She also got comment from Craig Renney

Renney also knew the restriction was for real, and never suggests – even though it might have suited his former boss if it really had been so – that it had all just been an unfortunate misunderstanding by a Treasury official.

(As it happens, in that Reserve Bank OIA there is a copy of the questions for the interviews the Board sub-committee (Quigley, Orr, and Chris Eichbaum) conducted for short-listed candidates for the MPC. It is interesting, although not conclusive on its own, that none of them invite candidates to offer any serious thoughts on monetary policy, frameworks etc. Note also that Chris Eichbaum – a VUW academic with Labour connections – used to be quite active on Twitter, and was not shy of disagreeing with comments I made about the Board or monetary policy, and never once suggested that the blackball didn’t exist, that it was all just a mistake by a Treasury official. Nor, of course, has Orr – not usually a shrinking violet when he thinks other people have the wrong end of the stick.)

Anyway, all that was the public record until 21 June when the new Tibshraeny article appeared. These were the key lines

From Robertson

and from The Treasury

I’d lodged an OIA with Treasury (maybe should have lodged one with the Minister too, but didn’t so) seeking to understand why they had said what they were quoted as saying. I got the entire 111 pages back on Friday afternoon.

Treasury OIA reply Aug 2023 re the MPC research blackball

Perhaps it amused Treasury to let me know they read my blog since the very first document released (but probably out of scope) was this advice from the manager of the macro team to colleagues in the media and governance bits of Treasury.

The Treasury comments were prompted by this request from Tibshraeny

Note that her request was cc’ed to media people in the Minister’s office and at the Reserve Bank.

I’m not entirely sure where she got the idea from that the 2019 line had been an error, although she illustrates her point by reference to Bob Buckle. I dealt with that point in my June post

Since then Buckle has finally delivered a conference paper (which I wrote about here) but that is 2023 and there seems to be no doubt that the blackball, if it once existed, does no more.

And this was the official Treasury reply

And this was not something just cooked up at a working level by junior staff. Two Treasury DCEs appear on the relevant email chains, as does the comment that the draft would be cleared by the Secretary’s office and sent to the Minister’s office before it was finally released to the Herald.

All the claims here about the 2018/19 process are simply false. Senior Treasury officials seem to have allowed themselves to be gulled into taking at face value an attempt by Neil Quigley, chair of the Reserve Bank’s Board (and Vice-Chancellor of Waikato University) to rewrite history, all the easier for them to do as it seemed to involve simply tossing under a bus the former Treasury manager (who signed out that 2019 paper) who no longer works there.

There is bit more context in the first draft response prepared by the current Manager, Governance and Appointments and the Treasury manager who was responsible for macro policy in 2019 (Renee Philip)

Later in the release we learn that in March this year Philip had had a meeting with Neil Quigley

This is a strikingly uncurious email (from an experienced manager to the Secretary to the Treasury and to the Deputy Secretary, Macro), in which it appears not to have occurred to her that the Bank and the Minister had defended the restriction in public (more than once), or that people who had been in a position to know – McDermott and Renney – while disagreeing with the policy had never once suggested it was all a misunderstanding. Or that the Bank’s defence of the restriction had used very much the same words – re future appointments – as were in the now-contested 2019 Treasury report. (And although she had apparently read my posts on the subject had not internalised the report of a qualified person who had explicitly been debarred from consideration.)

Quigley also cleared the Treasury June 2023 statement. Here is what he had to say then

(Nick McBride is the Bank’s in-house lawyer)

So we are supposed to believe that a fairly hands-on Board chair (there are lots of emails from him in various OIAs) simply wasn’t aware until this year of lines Bank spokespeople had explicitly addressed in 2019 (and again apparently in 2022) about a process he had been one of the key players in. The Tui ad springs to mind.

But none of it rings true. Perhaps no one at the Bank saw the initial Treasury report when it was written in January 2019 (although it seems not very likely given that the paper trail shows active engagement with the Bank and Quigley re MPC appointments issues in late January 2019) but it is beyond belief that Renee Philip hadn’t seen it (even though her comments suggest the macro team only really became aware of the issue after the OIA release in July 2019) as not only does the paper trail show that the request from the Minister’s office for the paper came first to the macro team but there is an extensive trail of emails from that time (Jan/Feb 2019) on MPC appointment issues which typically have both the manager, macro and the manager, governance and appointments on them. It seems very unlikely the macro team did not see the final (short) report. And there is also no sign – in the paper trail or his later comments – that the Minister or his senior staff read the Jan 2019 report and said “no, no, you’ve misunderstood, I never agreed to any bar like that”.

But, as it happens, we have contemporary lines from Quigley from the OIA the Bank released to me in 2019.

Mike Hannah was at the time the Board Secretary. He records the Board’s discussion the previous day, in a summary to be sent on to the recruitment consultants, in which the observations from the Board included “an academic researcher active in the Bank’s areas would likely be conflicted”. And Quigley welcomes the summary with no cavils or suggested amendments. It isn’t exactly the same words as turn up months later in the Treasury report but it is strikingly similar to those words (which Bank spokespeople later defended). It also aligns with the report from such an academic who had engaged with the recruitment consultants and with Quigley himself at the time.

The snippet is also interesting because it illustrates that at this stage of the process neither Buckle nor Harris were in frame, and casts further doubt on Quigley’s 2023 claim that in 2018 the Board had actively considered active macro researchers. Buckle comes into the frame a little later in this email from Hannah to Board members suggesting names proposed by Bank senior management. Note that Buckle is treated as a “former academic with an interest in policy”, not as an active (macro) researcher.

Now, 2023 Treasury officials cannot necessarily be expected to have had all this at their fingertips (although the relevant OIA was sitting on the Bank’s website, and Treasury does have a heightened monitoring role re the Bank), but what staggers me is the lack of critical assessment of the Quigley story.

Now, as it happens that is not universally true. In the latest Treasury OIA we find

Leilani Frew is the DCE responsible now for the governance and appointments function (and Stella Kotrotsos’s senior manager). Her instincts look to have been quite right…..but there is nothing else in the pack suggesting she did anything with them.

There was also this

James Beard is the Deputy Secretary, Macro. His instincts, while more limited, also seem to have been right, but again there is no sign his unease went anywhere either.

If either Frew or Beard were junior figures perhaps you might not be surprised they were ignored, but these are two of the most senior figures in the Treasury. It doesn’t reflect very well on them or on the Secretary or her office (whoever finally signed the statement out). Or, for that matter, on the managers past and present involved in responding to Tibshraeny’s request. You hope the standards they bring to their economic and financial policy advice are rather higher.

But if senior Treasury figures showed themselves gullible and too willing to go along, they weren’t the ones who perpetrated this exercise in mendacity.

I’d really prefer there to be a charitable explanation of Quigley’s comments. Perhaps if it was the June ones alone one might put it down to being caught on the hop on a busy day – he has a fulltime job and universities seem to be in some strife – but those comments are substantially similar to ones he is reported as making to a Treasury official in a scheduled meeting months earlier. It is hard to see any credible explanation other than an embarrassed attempt to rewrite history (would you want to be remembered as the academic economist who was responsible for banning active or future researchers from your country’s MPC?). In Orwell’s 1984 the bureaucrats literally rewrote the old papers. Thankfully – and for all their limitations – we have the private media and the Official Information Act.

If I was Treasury I would be fairly deeply unimpressed (as well as somewhat embarrassed myself), and if I were Tibshraeny the idea that I had simply been lied to by senior officials (directly and indirectly) wouldn’t have gone over terribly well either.