The government-appointed (and reappointed) chair of the Reserve Bank Board has been in the news today, after the reports earlier this week that in his role as Vice-Chancellor of Waikato University he’d been negotiating policy around a future new medical school at Waikato with National’s health spokesman Shane Reti. I don’t have any particular problem with such talks per se but what caught attention was this spectacularly inappropriate line

Reti seems to be a person of decency and integrity and one can half imagine him wincing when he read those words. Who, he might have asked himself, is the senior person who not only runs a public university but also chairs a major government board, who actually says such things, let alone writes them down.

There is also a (paywalled) Newsroom article this morning [paywall now lifted here] on Quigley, explicitly questioning his ability to keep holding the Reserve Bank job. I don’t think Quigley is a political partisan (National or Labour) – and he has had roles from both National and Labour governments – but he again displays a serious lack of judgement and tone-deafness (of the sort that was on display when he finally got one of his RB Board members to step down from an insurance company directorship, not because having such a role was a terrible look but because the OIA might lead to some scrutiny, or had never raised a concern at the government appointing the chair of Kiwibank’s then owner to the board of the bank regulatory agency). He can’t match the Governor for lowering the standing and reputation of the Bank – but then for the Governor it is a fulltime job – but it is a pretty consistently poor and damaging record.

And then there was the question of the ban put in place in 2019 on appointing people with active or likely future macroeconomic research expertise to the initial round of Monetary Policy Committee vacancies. It is clear that there was such a ban (now removed for the round of vacancies coming up next year) and that the Minister of Finance and the Bank’s Board (chaired by Quigley, with Orr a member who had to be formally consulted as well) had agreed on the ban.

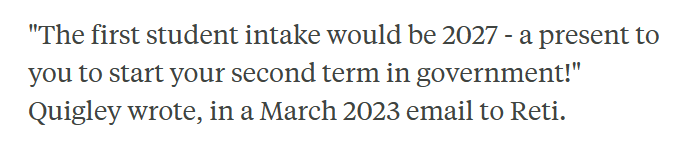

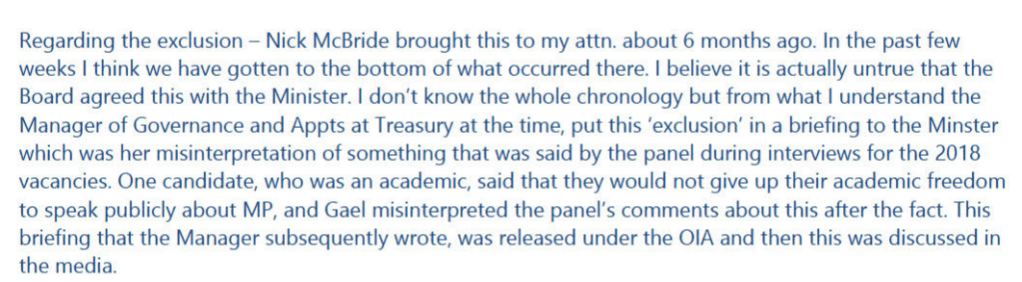

Quigley claims otherwise. That there never was such a ban, that it all a castle built in the air on a paper written to the Minister of Finance (released to me in 2019) by a Treasury manager responsible for governance and appointments. He had had, he claims, no idea until last year where such curious, incorrect, ideas (of the sort people like me and Eric Crampton, and fulltime journalists, notably Jenee Tibshraeny, now of the Herald) had been writing about had come from. This was the extract in question.

Quigley even got Treasury and the Minister to say in public that it had all been a misunderstanding, and that there had never been such a ban.

About a month ago I wrote a long post based around an OIA response from The Treasury in which I had asked for background relevant to that Treasury statement. I outlined what Quigley had told Treasury twice, months apart, earlier this year, and compared it carefully to what had been revealed in (a) past OIAs from the Bank and Minister, (b) things I knew from first hand accounts, and c) comments from the Minister, the Bank, former Reserve Bank Assistant Governor John McDermott, and former ministerial adviser Craig Renney. I pointed out that the ban had been commonly and widely understood, not just among Reserve Bank watchers in New Zealand but in markets overseas (a Treasury manager reported having been challenged on it in Australia), and not in ways that were welcoming – more along the lines of derisive comments that the Reserve Bank of New Zealand was the only central bank in the world where actual research expertise would have been a formal disqualifying factor. As I had noted in one post, not even Trump’s Fed appointment standards had dropped that low. There had been plenty of opportunity for Quigley and the Bank (or the Minister) to have corrected the story at any time over several years, and Orr in particular has not been backward in coming forward when he thinks people aren’t representing him or the Bank in a way he likes. I’d encourage you to read that post as I don’t want to repeat it all here.

At about the same time as the Treasury OIA had been lodged back in June Eric Crampton and I independently lodged (somewhat overlapping) OIAs with the Bank re aspects of the blackball and its removal. Being the Bank, they were very slow to respond but we both finally got responses on Tuesday. There is a couple of hundred pages of material, although bulked out by releasing back to us both the 42 page response the Minister had given me in 2019, which they had probably in turn just got from my website (it was in the mix because last year a senior Bank official sent it to Quigley, who then started on his “no, no, that wasn’t so at all” line.) Both responses are linked to below (Eric’s first – with his permission- then mine which came in two separate big documents).

RBNZ OIA release to Crampton Sept 23 re MPC expertise blackball

RBNZ OIA release to MHR Sept 23 re MPC expertise blackball Part 1

RBNZ OIA release to MHR Sept 23 re MPC expertise blackball Part 2

The documents make interesting, and slightly depressing even incredible (literally almost unbelievable), reading in places.

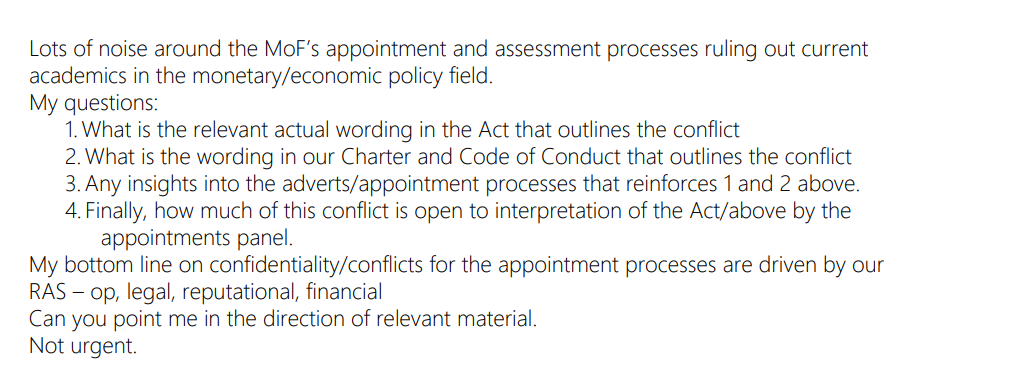

The document set starts on 18 May last year when the Governor (Board member) sends an email to Nick McBride (the Bank’s in-house lawyer) cc’ed to his boss (one of Orr’s DCEs) asking about whole situation re ”criteria and expectations” for external MPC members, noting

McBride says he doesn’t really know what went on (“as far as I know it was worked out between MoF and the RBNZ Board”) while noting (quite correctly) that there was nothing in the Act or the MPC charter or code of conduct that required or reflected a blackball on expertise. (Among outside critics I think this has been common ground all along. It would have been even more absurd had the law somehow enforced the ridiculous ban.) McBride comes back later that day with the extract (above) from the 2019 Treasury paper, pointing out that it had been released to me and had been what had sparked the coverage. McBride disavowed any knowledge of what had happened beyond that account. Neither he nor Orr seem to be in any doubt that there was such a restriction put in place for the 2019 appointments.

Nor had there been any doubt earlier in 2022, when Tibshraeny had been asking about the blackball in the context of the approaching expiry of the terms of two external MPC members. The Bank knew then, but outsiders did not, that the plan was simply to reappoint the incumbents so inside the Bank it appears the issue hadn’t arisen until Tibshraeny got what was probably a throwaway line from the Minister in a press gaggle, that he wasn’t aware of any change of criteria, and she then sought comment from the Bank. No one in any of the emails seems to have doubted that there was a ban – no one seems to have known much – but they just wanted to put Tibshraeny off (‘best not to throw any chum in the water’) so they agreed also just to line up with the Minister and say “no change”. So relative to what we previously knew, it is probably safe now to say there was actually no new information in those 2022 comments from MoF or the Bank. There is no record of them having consulted either Orr or Quigley at that point.

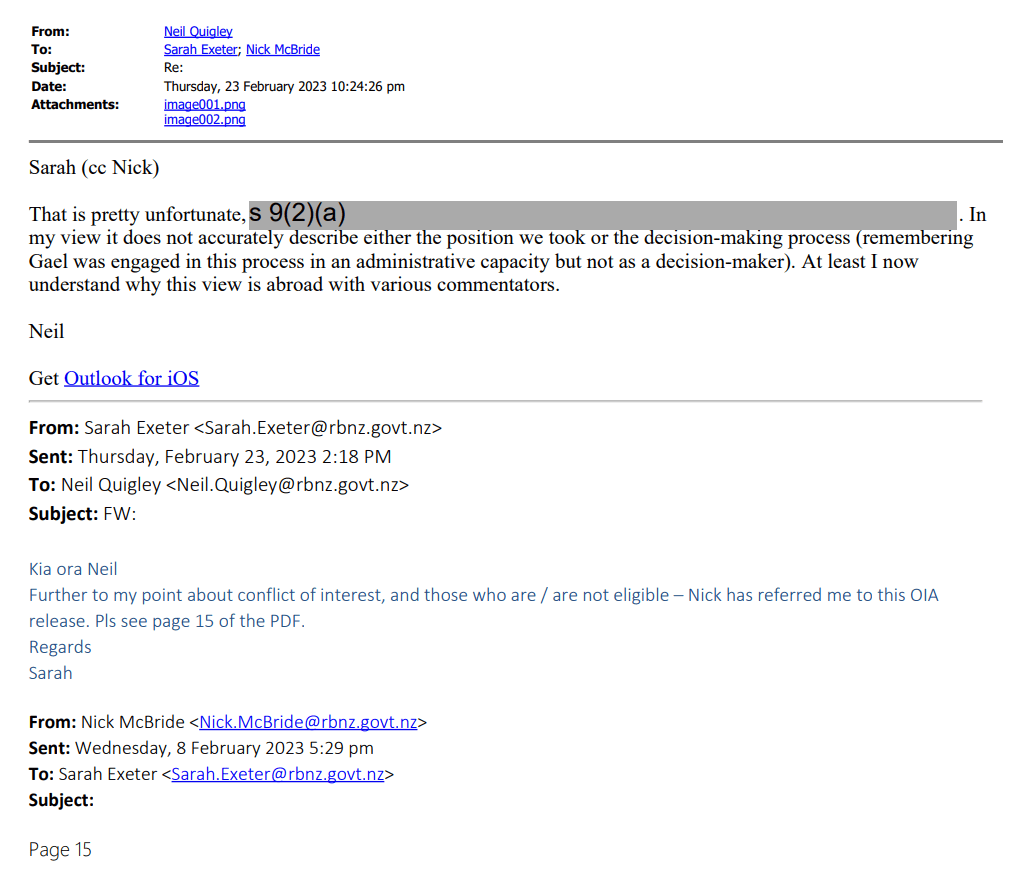

The final bit in the response to Eric Crampton was this from February 2023, when work was going on on the process and criteria for the next set of MPC expiries/vacancies. McBride and one of Bank’s governance people explicitly draw Quigley’s attention to the 2019 paper (Gael is Gael Webster, the Treasury governance and appointments manager who had signed out the paper). Note that section 9(2)(a) is a withholding ground around personal privacy: we might wonder whose.

It is pretty extraordinary, if this were an honest account, that the Board chair had never once in the previous 3.5 years asked someone why this view – that there was an expertise blackball, which he says he was aware of – was abroad. Extraordinary and not at all plausible, given that until last year the appointment of MPC members and of the Governor was the single most important powers the Board had.

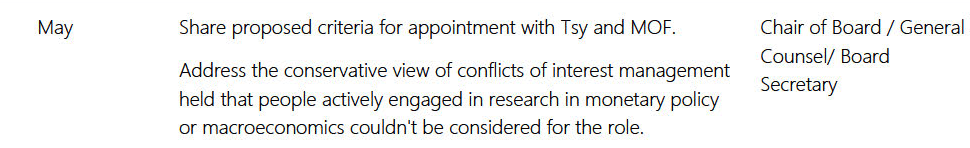

My OIA had covered only material from this year and picks up in mid-February (just prior to that exchange with Quigley) as staff are reviewing processes etc for advertising for MPC vacancies. (Interestingly, the Comms manager suggests this would be a good case for pro-active release of relevant material, not a concept the Bank displays any practical sympathy with ever). The draft document they are commenting on includes among the things to be done

and in comments McBride recognises the ban, commenting that “the board needs to be clear about its attitude to including MP [monetary policy] subject experts on the MPC and this should be resolved at the outset.

The Economics Department is a bit slow with its comments, and didn’t comment until the next draft in early March. Chris Bloor, one of their experienced and respected managers, observed

to which the person leading the process responds

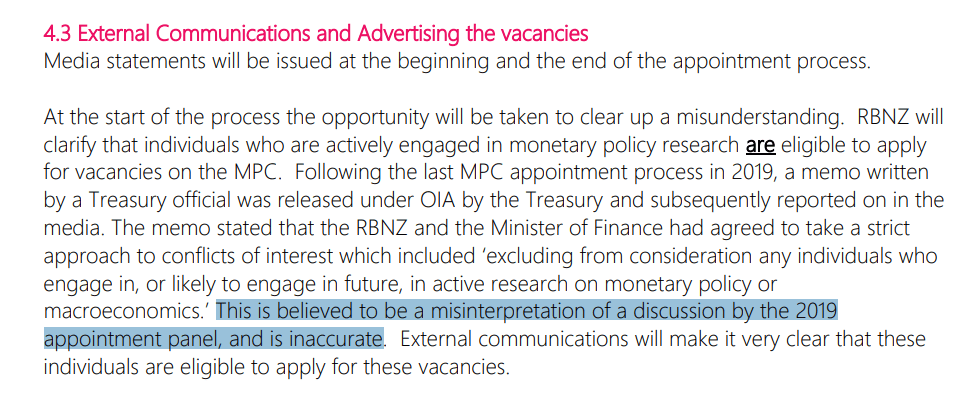

But they really weren’t very sure. In early April a paper went to the Reserve Bank Board on the MPC appointment process and it included this

And that was all that was new in the papers relevant to the issue. Note that there is no suggestion that anyone made any effort to contact Treasury or Gael Webster specifically, they simply went along with a story Quigley had given them years after the event. It seems not to have occurred to anyone (or perhaps it would be lese-majeste in today’s RB to have done so) to ask “but what about all those statements that have been made in defence of the ban previously?”, or “but if so many people had got the wrong end of the stick outside and abroad, why did we never clear up the confusion?”

I’m quite prepared to believe that there was an interview with an academic applicant (recall that academics themselves weren’t barred, and (non-macro) Prof Caroline Saunders was appointed), who told them “they would not give up their academic freedom to speak publicly about MP” [as MPC members in many other countries do speak] but on the most charitable interpretation Quigley must have been conflating two quite different events and sets of circumstances.

As I discussed in the earlier post, all those years ago a qualified academic told me that they had contacted the recruitment firm the Board was using and been told that they would not be considered because they did and might do in future macroeconomic research on matters relating to monetary policy, and that this was a criterion choice adopted by the Board. The same academic then saw Quigley at a function and asked him about this apparent ban, including if it was really the Board’s view. As recounted to me, and repeated recently, Quigley’s response was along the lines that they wanted to be very cautious and risk-averse for the first set of appointments and that the criteria might be relaxed in future rounds. That was well before anyone was longlisted, let alone shortlisted or interviewed. My interlocutor couldn’t even get on the page to be asked about how they would operate in practice if appointed. And you will note that that conditional statement about future appointments is very similar to the wording used in that 2019 Treasury memo that Quigley now seeks to disavow, throwing the author under a bus.

And how about some of the evidence I cited in the previous post? Here Quigley raises no objections to the Board Secretary’s account of a Board discussion of individuals and (see highlighted bit) criteria.

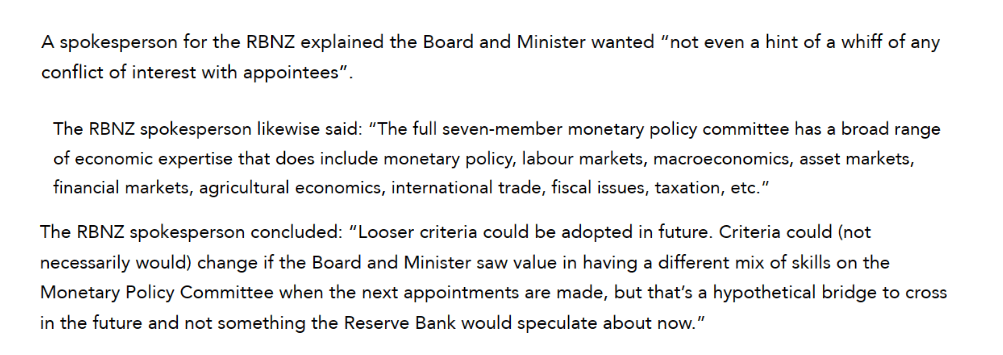

Here was how the Bank’s spokesperson was defending the blackball in 2019. Note the explicit use (their own words) of the line that “looser criteria could be adopted in future”.

And here was the Minister of Finance’s defence of the blackball in 2019; he also explicitly stated “over time this will evolve”.

There is simply no evidence for the (contemporary) Quigley version of events – the one he got Treasury to embarrass itself by making a statement defending (having asked no questions themselves, but happily tossing a former staff member under the bus).

(Having read the latest OIA releases I went back this morning and read the Bank’s 2019 release to me on matters around the MPC selection and appointment process. On rereading it I noticed that they had not disclosed any communications to or from the recruitment firm (nor identified such material with statutory grounds for withholding). A new OIA has been lodged this morning which may yet shed some new light.)

It is quite clear that there was a blackball on expertise (which has now, formally, been removed) and when Quigley told Bank staff and Treasury (twice) that it was not so, at best he was confused, and at worst deliberately trying to lay a false trail to cover later embarrassment at such a bizarre rule, all while deflecting blame onto an experienced professional who had been working for another government agency. Neither option reflects any credit on Quigley or the Bank whose performance he is supposed to oversee and hold to account. Once again it brings the institution into disrepute (though more so him as an individual and statutory officeholder).

One is always suspicious of what isn’t in these releases. There is relevant material that has been in other releases, including from Treasury, but not released in this set, and there is no record of any discussion (written or oral) between the Governor and his Board chair about any of these issues. That simply doesn’t ring true. But whether true or not, there is quite enough material in what we do know to conclude that, wilfully and deliberately or not, Quigley was simply not telling an accurate story when he has tried to convince staff and Treasury that there never was a blackball. He should be held to account for that. He should not – for this and a variety of other reasons – be the chair of our central bank and banking regulator, from whom we should expect openness. transparency, integrity, accountability….and the humility to acknowledge honestly when mistakes have been made (in this case both the blackball itself and the spin, attempting to rewrite history at the expense of others).

UPDATE: Eric Crampton has a follow-up post in which he bends very very far over backwards to find a charitable explanation. I don’t find it persuasive, and he doesn’t take account of several important items above, but it is worth reading as an alternative take.