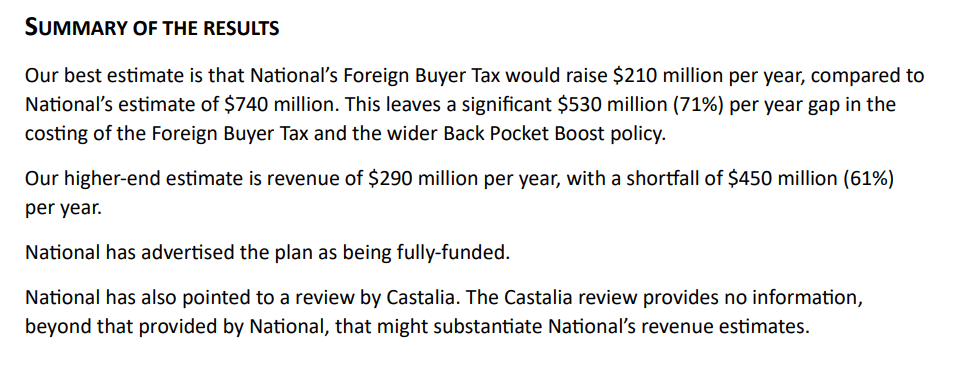

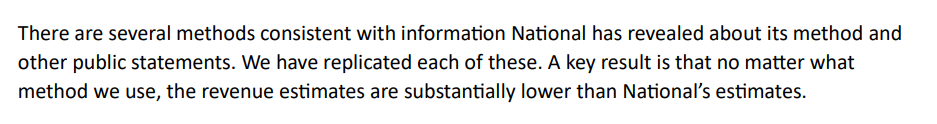

The National Party’s “Back Pocket Boost” tax and spending plan, announced a couple of weeks ago, included a partial lifting of the foreign house buyers’ ban, to be replaced with a 15 per cent tax but only on properties selling for at least $2 million. “Foreign” here is a shorthand: the tax affects non-citizen purchasers who do not have a residence visa for New Zealand. Moreover, it does not (as the current ban does not) affect or constrain Australian or Singaporean purchasers.

My initial interest in the package was mainly macroeconomic, including noting that a fully-funded package made no inroads on the (large) fiscal deficit, and that it might actually add a bit to inflationary pressures, including because the revenue from the foreign buyers’ purchase was probably not going to be generated from New Zealand incomes and the income tax cuts were going to people with a high marginal propensity to consume. The revenue estimates from the foreign buyers’ ban seemed quite high – and are quite important to covering the costs of the package – but that seemed to be an issue other people could think about.

But as the debate began on that specific point I got interested. Initially still mainly as observer. As someone who has long been sceptical of the case for a state-funded policy costing office for political parties, I did a post observing that the political market seemed to be working: questions were being asked, experts were coming out of the woodwork, and in light of what emerged (including the party’s choice to, or not to, publish their detailed estimates) voters could reach their own conclusions. In the end, precise numbers were likely to matter less than what the whole episode told us about the group that aspires to form our government in a few weeks’ time.

But then Sam Warburton approached me about getting involved in an exercise with him and Nick Goodall of Core Logic that would attempt to use what National had described of its methods and assumptions to see (fairly mechanically) how much revenue the policy would be likely to generate, using that approach. I don’t support any political party but my inclinations tend to be more right-wing than otherwise, and Sam is fairly well to the left. But there are plenty of issues economists can generally agree on – the general disapproval of Labour’s GST policy being another – and here the issue wasn’t one of whether the tax was a good idea (I don’t think so, and would rather lift the ban altogether), but simply how much it would be likely to raise on credible assumptions. It was and is essentially a technical issue. Oh, and since I don’t approve of state-funded policy costing offices, there was a bit of a sense of obligation to do my bit.

The paper we came out with is here

review-of-nationals-foreign-buyer-tax-revenue-estimates-final (2)

The summary of the paper is here

The point of this post is not to repeat everything in the paper, which is a deliberately narrow exercise (and which seems set to have quite a bit of media coverage anyway). But I should note that both in the note, and in the discussion in this post, it is simply assumed that tax and trade treaties don’t in the end pose obstacles to implementing the tax much as National has described it. We proceed as if it can be implemented that way, leaving any treaty issues to the lawyers.

To understand what was done in the paper, we assume:

- foreign purchases (over $2m) occur in the same TLAs (and old Auckland TLAs) as prior to the ban (that means disproportionately, although far from exclusively, in Auckland),

- foreigners buy the same priced houses as locals (we have detailed data on the distribution of all sales by price band in each TLA),

- to ease the constraints of the $2m threshold, potential foreign purchasers will routinely be willing to pay $2m for houses that would otherwise trade at anything above $1.75m.

If one were thinking in terms of risk, the 2nd bullet may understate likely sales, but the 3rd would overstate them.

Reasonable people can produce quite a range of estimates, using approaches inspired by what National has described and other possible approaches. The plausible range is at least as important as any specific numerical estimate. Accordingly, I want to take a slightly more discursive approach to the issue of how much revenue can be raised, and how best to think about it. That includes questions about how much revenue we might reasonably think the tax would raise, but also what the implications are if we are roughly right and National is wrong.

Here I would add that one of the most surprising things about this entire episode is that National has never made any attempt to send out expert surrogates of their own, who might have been willing to champion in technical detail the party’s numbers. I don’t really expect Willis or Luxon individually to be all over every modelling detail, but they should have people who are, and people who are able to tell the story behind the numbers. As it is, no one (other than National’s own claims) who has looked into the matter seems to think the tax will raise anywhere near $740 million per annum. If there were even one informed commentator championing, with a detailed story, numbers that high or higher we’d all stop and take note. But there aren’t.

Standing back, the main question we face in assessing the plausibility of National’s revenue estimates is the volume of sales that would be made to non-Australian non-Singaporean foreign buyers under the proposed policy. There is also some uncertainty around the average price those buyers would pay. National has told us they assumed $2.9 million, and whether that is right or not the average clearly cannot, by construction, be below $2 million. To raise the revenue they estimate with an average sale price of $2.9 million there would need to be 1700 sales a year.

So an appropriate starting point for analysis is the previous experience with sales of houses (transfers) to foreigners (ie non-citizens without residence visas) buyers. Statistics New Zealand publishes a reasonably extensive range of data but only back to the start of 2017.

The ban came on for sales entered into from October 2018 (settlements a bit later). Once Labour was elected in late 2017, it was clear that the ban was coming and so sales/transfers in 2018 are likely to have been somewhat inflated by people buying while they still could, bringing forward demand and sales that would otherwise have been spread over the following few years. We also have data on the (substantial) number of sales each quarter to Australian and Singaporean buyers (the total of the sales that are still happening). A reasonable base level of sales prior to the ban seems to have been about 800 a quarter of which 150 a quarter would have been to Australian and Singaporean buyers (the latter making up more than half of sales to foreigners in the single most expensive locality in the country, the Queenstown Lakes District Council area).

Of course, world population has increased since 2017, as has the stock of houses in New Zealand. So perhaps if there were no ban at all and no tax, it might be reasonable to think of a starting point now of foreign sales of a bit under 3000 a year (plus the Australian and Singaporean ones).

If that many houses were sold to non-Australian non-Singaporean buyers each year at an average price of $1.5 million (well above the average New Zealand price and above even the average Auckland house price), the tax would raise $675 million, getting close to (but still not as high as) the numbers in National’s document. (As an indication of where average sales might go at without any restrictions, a number like this seems generously consistent with Vancouver data on the price the average foreign buyer was paying relative to the average resident.)

But….remember that houses can’t be sold to these sorts of buyers for less than $2 million, and relative to a no-ban no-tax environment the cost to these buyers is higher now than it was (higher in real terms just because all New Zealand real house prices are higher than they were five years, but more specifically higher because of the 15 per cent tax). One large group of people who might otherwise buy are still simply banned while the others face a fairly heavy tax.

There are two big uncertainties in getting from, say, 2017’s position for the number of non-Australian and non-Singaporean buyers to the regime National proposes.

The first is that there is no hard data on what prices those foreign buyers were paying before the ban. And for all the talk of high-priced Queenstown, we know there were more foreign sales in Christchurch (cheapest main centre in the country) than in Queenstown pre-ban, and about as many in each of Hamilton or Wellington as in Queenstown. Even Auckland is a very diverse place, and far from all the sales were in Devenport, Waiheke, or Epsom/Remuera. It isn’t likely removal of the ban on houses over $2m will reawaken effective foreign demand in Otara or Mangere. Pre-2018 buyers were themselves a diverse bunch.

And the second substantive uncertainty is how responsive demand in that over $2m price range will be to the higher prices the tax now imposes. People buying, say, a $2.5 million house in Epsom aren’t poor by any means, but they probably also aren’t money-no-object people either (and recall that the tax doesn’t apply to people living here permanently but to those without residence visas). These aren’t all, or even mostly, billionaires.

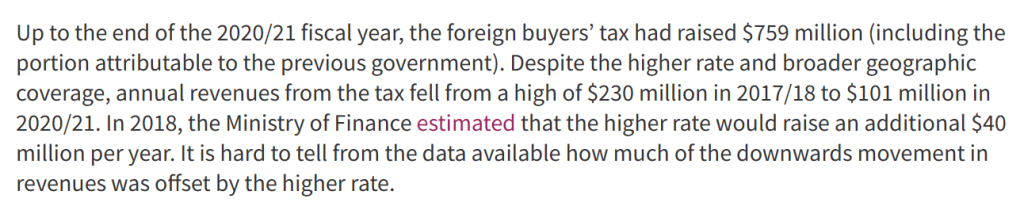

I’m not aware of any country that has put a price-threshold based tax on foreign buyers. But in their policy document National cites the experiences in Canada, where both Vancouver and Toronto had for a time a 15 per cent tax on foreign buyers (similar definition to New Zealand) but on all houses. Canada has a similarly encouraging immigration policy to New Zealand, and Vancouver in particular has an (apparently well-earned) reputation as a magnet for Chinese purchases of real estate. In both places reports indicate that the imposition of the tax substantially reduced foreign purchases (demand responded to the increased price the tax imposed). One formal paper I read estimated a 30 per cent reduction in demand. Other suggest perhaps a 40 per cent reduction. Our paper I linked to above deliberately does not attempt to include an estimate of this demand effect.

What do we know of the revenue these taxes generated in Canada? I’ve only been able to find scattered reports regarding Toronto – a city 20%+ larger in population than New Zealand – but what I have seen suggests revenue estimates from the 15 per cent tax rate on all foreign purchases and at all price points was around C$200m per annum (about NZ$250m). Toronto has very high house prices (and price to income ratios).

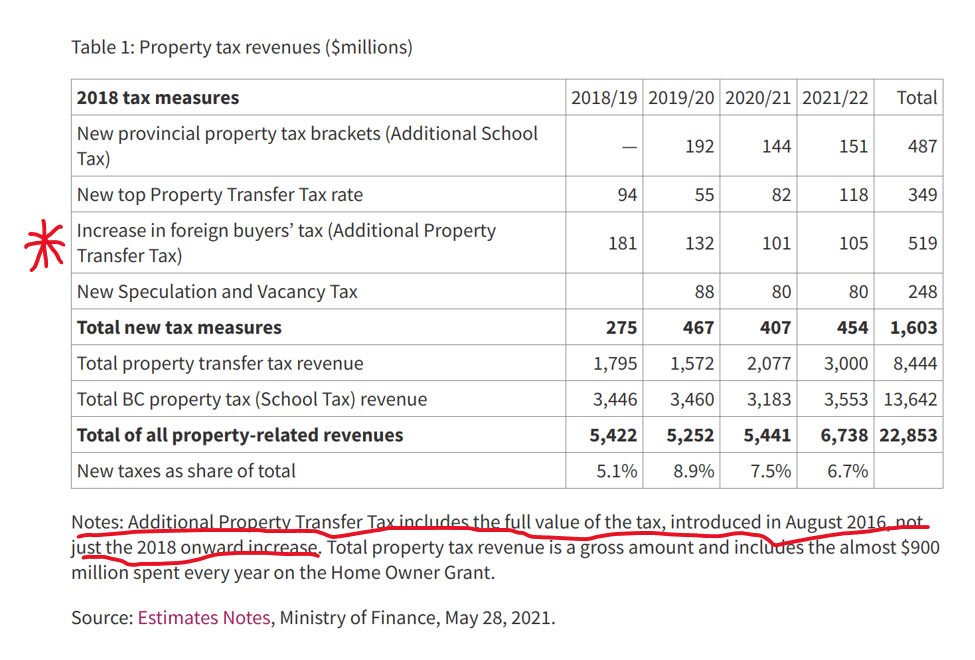

What of Vancouver? There I found references to official British Columbia revenue numbers (in this think-tank note). The tax was initially set at 15 per cent and then raised to 20 per cent in 2018,

and

C$180 million per annum (NZ$220m) looks to be a reasonable pick for a 15 per cent tax. And if metro Vancouver has only about half New Zealand’s population (a) their tax applied to all nationalities and all price points (on both points unlike National’s proposal), and (b) Vancouver has historically been more of a magnet for Chinese purchases that most other cities internationally (including Auckland).

If I had just arrived from Mars – or were an Opposition leader without the benefit of The Treasury wanting to do a reasonableness check on my team’s numbers – I guess I’d look around at various revenue estimates locally and try to triangulate them against what I could find about other countries’ actual experiences (remembering that places typically put these taxes on primarily to deter demand not to raise revenue). Perhaps such a tax raises quite a lot more than $200m or so in a normal year, but it wouldn’t be my first guess. I’d be a bit troubled if no estimate – not one – was in excess of my own team’s number.

Now here it is worth noting a couple of caveats that could help with revenue raising (and one working in the opposite direction). If house prices take off again I guess it would only be a few years until the average (not median) house price in Auckland was $2m. If so, a lot more potential buyers would be eligible, but….the government responsible might have other problems and concerns.

More seriously, it probably is reasonable to expect that in the first year of the new policy quite a lot more revenue would be raised. There probably is some pent-up demand, perhaps especially at the very top end of the market. But even if one doubled the first year’s revenue estimates, it doesn’t make much difference to the four-year view. The year in year out shortfall would still be substantial.

Note, however, that some of these foreign buyer tax regimes have provided a refund of the tax if the purchaser later establishes residence. That is not a feature of National’s tax policy so should not affect the current costings, but it is an issue to be aware of if the policy moved to being legislated

On the best estimate in the paper the annual revenue shortfall is $530m. That would also be consistent with the scale of revenue that appears suggested by the Toronto and Vancouver experiences. But the gap could be smaller: a $400m shortfall isn’t impossible given the inevitable uncertainties in the modelling and likely experiences. But a shortfall of $400-500 million per annum is a touch more than 0.1 per cent of annual GDP. This year’s deficit forecast in yesterday’s PREFU was 2.7 per cent of GDP, and that too is only a point estimate within a (not formally specified) range. 0.1 per cent of GDP is simply not macroeconomically significant. That is so in respect of fiscal policy, but it is also true of monetary policy. In fact, on its own the revenue shortfall would make little or no difference to monetary policy because as I’ve pointed out previously – although National continues to resist the claim – the revenue wasn’t mostly going to be coming out of what would otherwise be local demand anyway.

One could add – and I will because I have repeatedly made this point about policy costings offices – that no poll at present suggests that the National alone will have a majority in the next Parliament. Under MMP in particular, manifesto promises (especially detailed ones) are mainly signals of opening bids in the negotiations to form a government or settle on a legislative programme. If National wins, actual details are near-certain to be at least somewhat different from what was in the Back Pocket Boost package.

That doesn’t mean this is all a big fuss about nothing. First, the signalling matters. When the fiscal deficit as it as large as it is, a major political party promising tax cuts really should be able to convincingly suggest to the public that the cost will be fully covered and that if their programme was adopted it would not worsen the already-large deficit. National’s package does not pass that test at present.

And, more generally, how they handle episodes like this provides us as voters with information about the people who want to run the government in a few weeks’ time. An assured performance enhances credibility. Otherwise, not so much. An assured performance might have meant there were no major questions about any costings at all (at least from anyone other than cast-iron partisans) even in a high- profile package. It might also have meant that if/when questions started arising, you’d be able to release some enlightening report from the consultants you hired to check your workings, or you might release your own workings – or a nicely written up version – yourself, or got some well-informed surrogates to tell your story. Your leader might even have persuasive lines to assuage doubts. In this episode none of that has happened, and it has been anything but reassuring about just how much on top of their game, ensuring detailed stuff is done well Luxon, Willis, and their key staff advisers really are. It may also speak to their instinctive response under pressure: openness and engagement or hunkering down defensively. Probably hardly anyone is going to change their vote on this one specific (perhaps they shouldn’t – lots of things matter more), but that isn’t the test of whether these things matter. They do.

I haven’t mentioned Castalia’s role in all this. In my first post on the package I pretty much took for granted that I’d be able to count on that. But as our joint report notes, and having seen the [Executive Summary of the] Castalia report, it offered no basis for any reassurance at all on the foreign buyers’ tax revenue estimates. It explained neither what National had done nor indicated what robustness checks Castalia had made. In fact, the single half-sentence reference to the tax has a distinctly “last minute add-on” feel to it. One would hope it was not so. RNZ reports this morning that Castalia is standing by their review, but we simply don’t know what that review consisted of, so that assurance adds barely any useful information.

In closing I am going to repeat my opposition to a state-funded policy costings office. It is up to parties themselves to decide what work they get done on policies and what material they release, when and how. In this case, the existing system is working, putting a spotlight on National and their estimates and giving them choices about how they respond and us information that we can use in forming our views of the party and its leaders. Is it messy? Yes. Is the substance a second-order issue? In many respects, yes. But much of politics, and much of life, is like that, even if technocrats would generally prefer it was otherwise.

As for the issue at hand, whichever way you look at the numbers it is hard – but not impossible – to see the policy raising much more than $200m a year, and not at all that hard – but not perhaps likely – to see it raising less.

UPDATE 16/9

In the body of the post I used a Canadian think tank’s report on the Vancouver experience. That report quoted British Columbia Ministry of Finance revenue numbers, but I had not then got back to the source document. This table is from p321 in the PDF at that link.

Note that the parameters of the British Columbia interventions have changed repeatedly. They started with a 15% tax in Vancouver in (a surprise move in) 2016, and in 2018 both raised the rate to 20% but also extended the coverage to include some other areas including greater Victoria (another 400K people on top of Vancouver’s 2.6m). And from the following year’s Estimates Notes

Note that under the British Columbia tax rules you can receive a refund if you become a resident of Canada within a year of purchase. The data I have do not break about the scale ($m) of these rebates, but the gross revenue figures may be a bit higher than those shown in the Ministry of Finance table above.

Finally, on another aspect, this snippet is from the bit of the Castalia review that National has provided to some outlets (one of which gave it to us).

As an approach that seems fine. There are, however, no government estimates for the revenue impact of the foreign buyers’ tax.

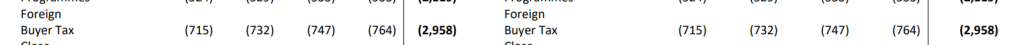

Later in the same document there is a table, showing “National modelling” numbers on the left and “Castalia modelling” numbers on the right.

For some items it makes sense that there is no difference (when using government estimates). In others, they describe where and why there are differences.

What is puzzling if Castalia really did model estimates themselves for the revenue from the foreign buyers’ tax is that they came to exactly the same numbers in total and each year. Reasonable approaches will almost inevitably come to slightly different estimates even if they end up in much the same ballpark (eg in this case perhaps differences in how one might think of first year effects as a result of pent-up demand).

My point is not that Castalia did not honestly believe National’s numbers (I’m quite sure they did believe them to be reasonable) but to raise again the as-yet unanswered question as to just how much in-depth analysis and review went on for this specific line item.