This morning’s post previewed PREFU at a high level, pointing out that both main parties had been in practice endorsing expansionary fiscal policy, and that the likely operating balance surplus that would be shown in the PREFU would really reflect nothing more solid than aspiration, even after the numbers had been gamed. Neither party seemed to have a concrete fiscal strategy or plan to actually close the deficit, a deficit which the IMF estimated a few weeks ago was one of the largest among advanced countries as a share of GDP.

As far as I can see there are no great surprises in the PREFU fiscal numbers. There is a small surplus in 2026/27, using the numbers the government told Treasury to use for its future spending plans. Anyone can plonk down a number. Delivering it is another thing.

There isn’t going to be lots of fresh analysis in this post, mostly (at least for fiscals) a series of charts I’ve shown on Twitter.

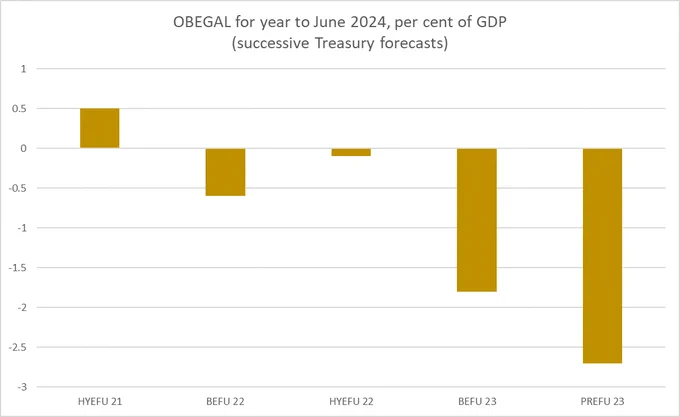

For example, here is how Treasury’s forecast of the operating balance (OBEGAL) as a share of GDP for the year we are now in has evolved just over the last 20 months.

The deterioration since the Budget this year is despite the economic position and capacity pressures (the output gap) being a bit less negative. This is a year for which the spending has now been appropriated, the taxes put in place etc.

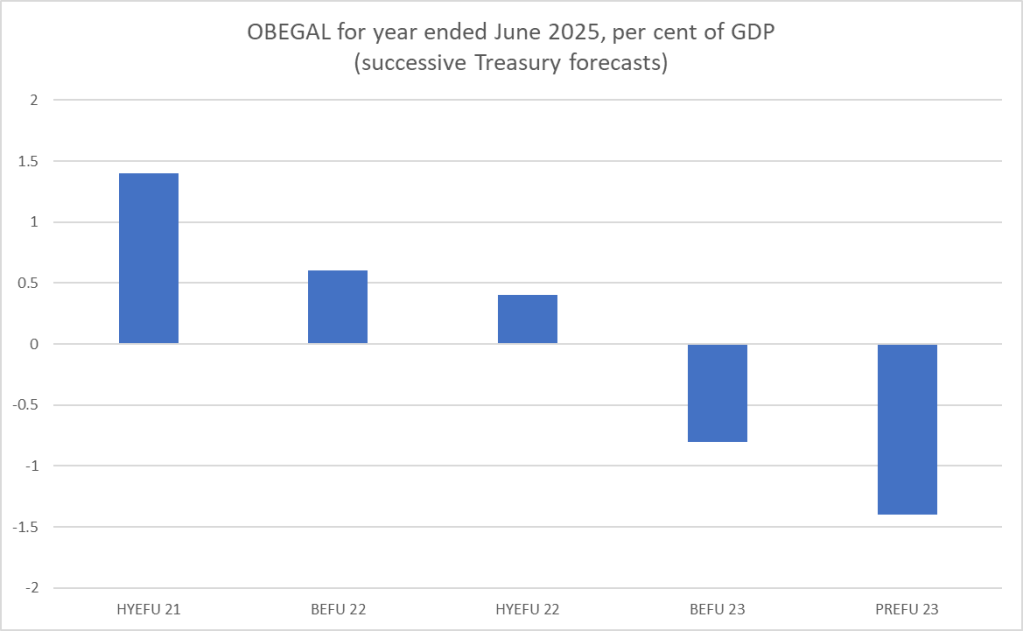

What about the following year?

We aren’t anywhere that year yet, but the forecasts have already revised down massively.

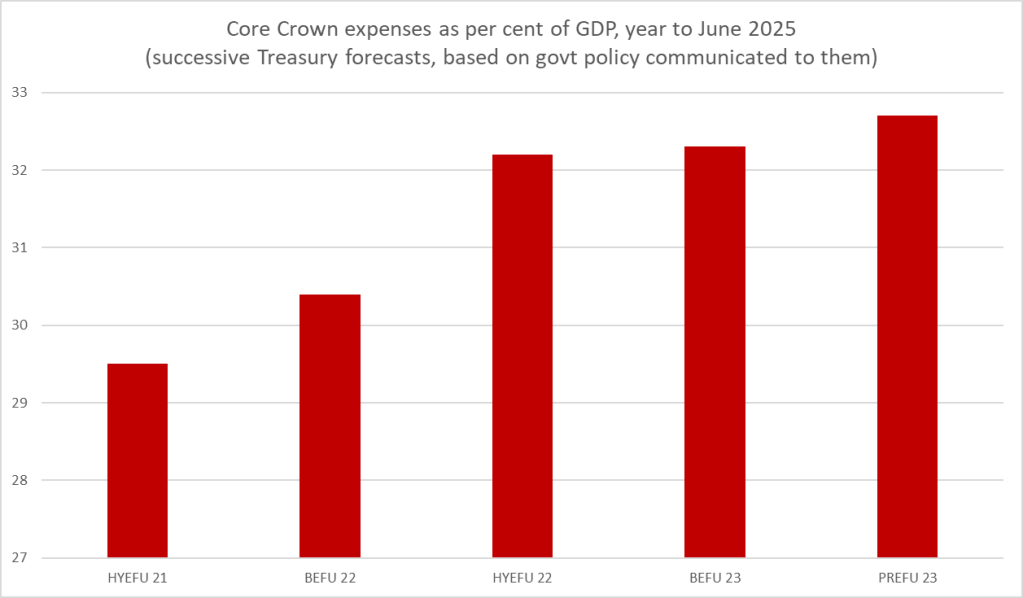

And despite recent talk of renewed fiscal discipline and spending restraint, here are the projections for core Crown spending as a share of GDP, again for the next Budget year. The PREFU forecast share is higher again than the BEFU one. And this is before Ministers actually have to confront drawing up next year’s Budget.

The political parties want us to believe that we are on a track back to surplus. We aren’t. Instead, the Secretary has been given some numbers to be consistent with a surplus by the end of the period, and for anything else…..well, we just have to wait for successive Budgets under whichever government holds office.

As for Treasury, they have to be a little diplomatic, but here is their text about spending and operating allowances, and my summary commentary

The medium-term numbers in the PREFU are just not a serious contribution to anything much. They distract more than they clarify or reveal.

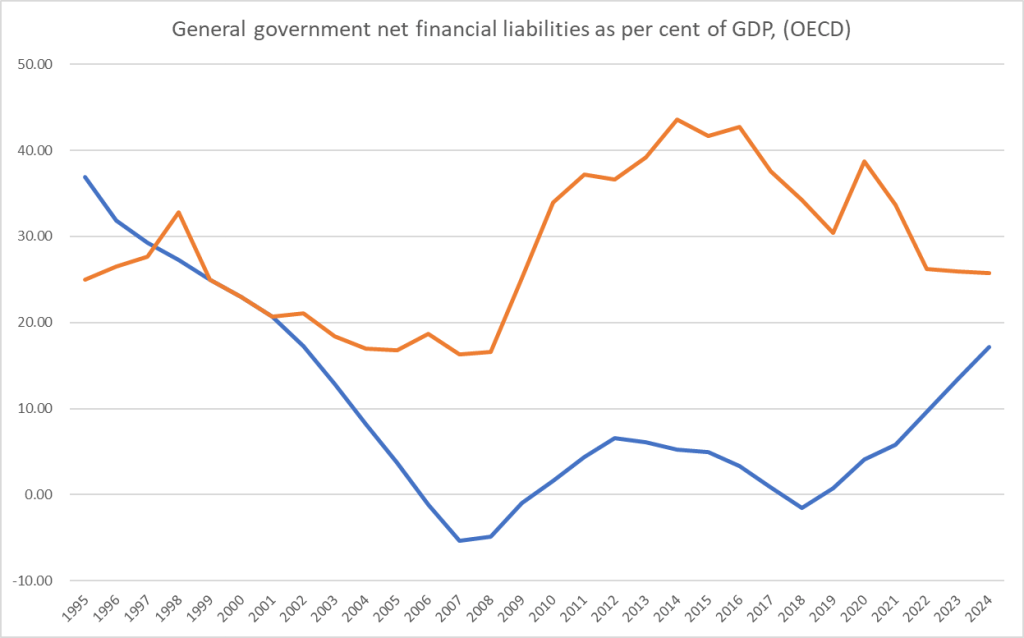

Whichever party forms the government they face tough choices over years if they were actually to be serious about getting back not to surplus, or even balance. If they aren’t serious then net debt will continue to rise as a share of GDP and within a few years we will have higher net debt as a share of GDP than the median advanced country.

I was also interested in the inflation and related numbers. Treasury is a bit more pessimistic than the Reserve Bank was in its last forecasts about how quickly inflation will come down. But they simply run with something like the Reserve Bank story of the OCR holding at current levels for some extended period.

There are odd aspects to that. For example, here is the inflation forecast to March 2025, 18 months from now – the sort of horizon monetary policymakers often focus on,

It is easy for your eye to focus on the fall in the inflation rate which, if it happens, will be a good thing. But note that 18 months from now annual inflation is still 2.7 per cent, well above the 2 per cent the MPC is supposed to focus on. All else equal, an outlook like that would normally suggest that further OCR increases were warranted. Treasury doesn’t show them, but then on OCR things they don’t really like being out of step with the Bank, and of course the Secretary to the Treasury, under whose name these forecasts are issued, is a non-voting MPC member herself.

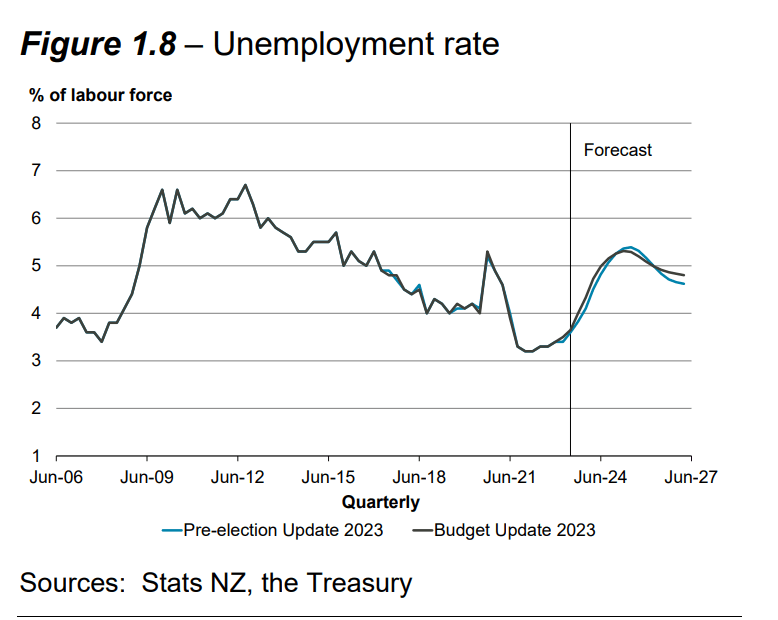

But what is a bit puzzling is how Treasury thinks that the inflation rate is going to come down so much at all. The unemployment rate, for example, never gets beyond about 5.5 per cent and doesn’t even stay there for long. It took materially higher unemployment rates for several years in the last recesssion to get inflation to fall much less than is needed now.

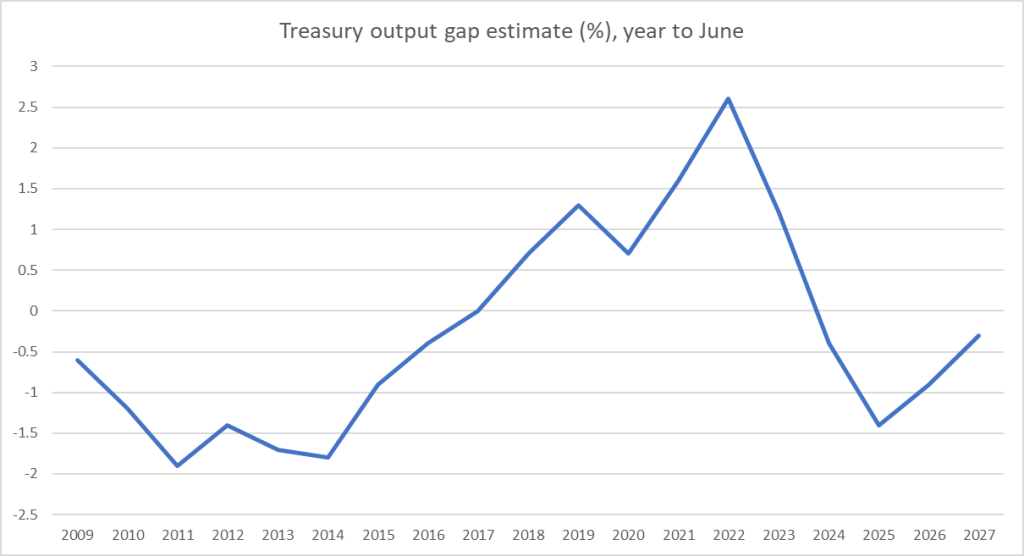

And what of the output gap estimates?

Yes, the output gap is forecast to go materially negative but only for one year, and we see in these numbers nothing like the sustained large negative output gap of the early 2010s…..again when the extent to which core inflation fell was nothing like what is being sought this time.

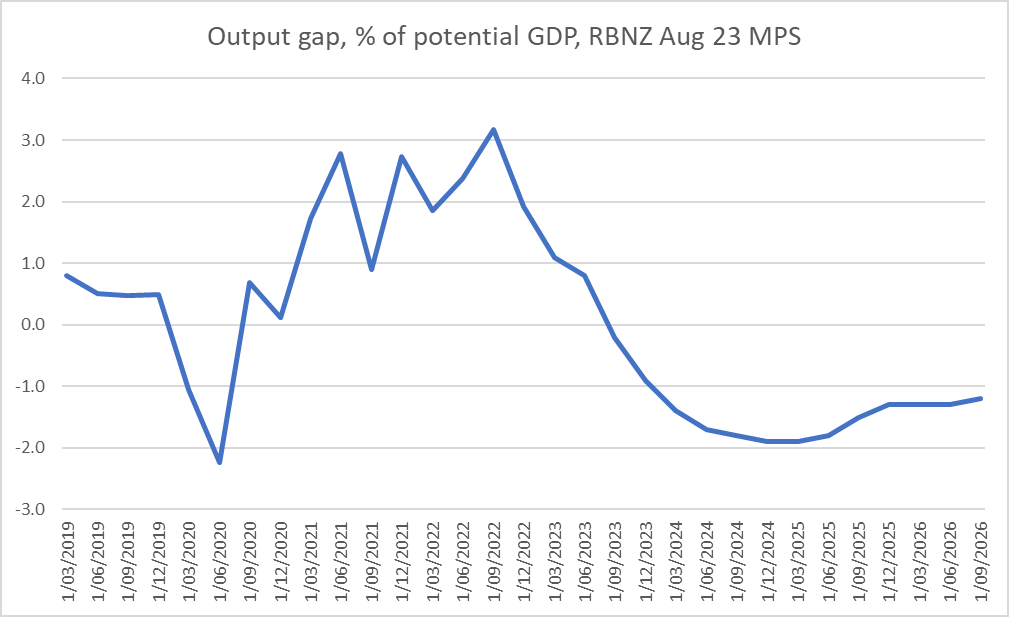

By contrast, the Reserve Bank’s numbers from their latest MPS tell a more consistent story

It simply isn’t clear on what basis The Treasury expects core inflation to fall so far so (relatively) fast: core inflation is expected to roughly halve over the next year even though the output gap over the year to June is barely negative, and unemployment by next June is still only 4.8 per cent, barely higher than what Treasury seems to regards as a NAIRU.

Perhaps expectations will do the bulk of work. If you wish really really hard and truly believe then…..Treasury seems to say – you can have core inflation a long way down without anything too nasty economically along the way.

Perhaps…

(Finally, and incidentally, Treasury seems to assume some reasonably robust productivity growth over the forecast period. I’m not at all sure why, or on what basis?)