For the first 20 years or so of inflation targeting in New Zealand, there was a near-constant hankering for other instruments to “help out” monetary policy. In the early days of getting inflation under control, it was little more than ritual incantations (the team I ran included them every month in our papers to the Minister) that it would help, adjustment would be easier, if only there was labour market deregulation, reduced trade protection, and tougher fiscal policy. In the Brash years, his colleagues became very familiar with the Governor’s hankering for what we (or he) called “tweaky tools”, things that at the margin might make a difference, particularly perhaps in easing the exchange rate pressures that used to be such a feature of New Zealand monetary policy tightening cycles. There was even the pesky visiting US academic in the mid-90s who used his public lecture to suggest that discretionary fiscal policy should be handed over to the Reserve Bank (we winced). It wasn’t so different in the pre-2008/09 Bollard years. At the then Minister’s urging we and Treasury ran an entire Supplementary Stabilisation Instruments projects in 2005/06, culminating a year later in a scheme for a discretionary Mortgage Interest Levy, a scheme the then Minister was tantalised by, sufficient to consult the Opposition, but eventually shut down work on only when National walked away. At about the same time, yet another invited visiting academic was openly proposing a variable GST as a supplementary stabilisation instrument. In the same vein a few years later, Labour in 2014 campaigned on giving the Reserve Bank power to vary Kiwisaver contribution rates, to assist monetary policy in the cyclical (inflation) stabilisation role Parliament has assigned it.

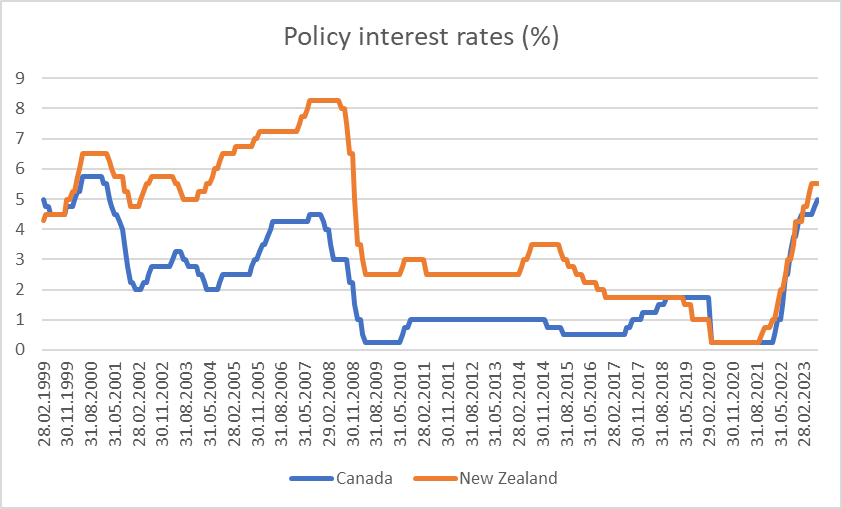

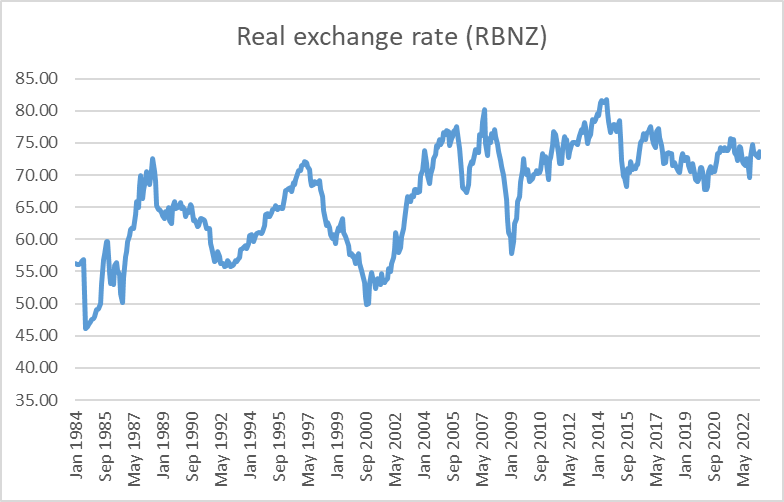

Of course, between mid 2007 and mid 2021, there were hardly any OCR increases, and those there were were quite small and short-lived (unnecessary in the first place as it happens). And since around 2010 New Zealand real exchange rate fluctuations have been much more muted than we had become accustomed to (over the decades from 1985, they were not only highly salient in political debate but also inside the Reserve Bank).

And if big cyclical swings in the real exchange rate still haven’t resumed, big OCR increases have.

And with it talk of spreading burdens, easing loads, and finding supplementary tools seems to be back. There was an article in the Herald a couple of weeks ago sympathising with indebted households who, it was claimed, are bearing the brunt of the belated anti-inflation fight.

(I wouldn’t usually be very sympathetic with people who took big mortgages when house prices were rocketing on the back of pandemic-policy low interest rates and didn’t lock in, say, five or seven year fixed rates, except that……..the Reserve Bank itself by buying up $50+ bn on longish-term government debt at the same time did rather tend to suggest to the borrowing public that rates weren’t likely to go up much – after all, which responsible government agency would expose its stakeholders (taxpayers) to a meaningful risk of $10+bn of financial losses.)

And that prompted Don Brash to enter the conversation, reviving a call he had first made in 2008 and suggesting that the Reserve Bank be given the power to vary the petrol excise tax as an additional counter-cyclical tool to assist monetary policy and spread the burden. This is reported and discussed in this Herald piece today, which in turn draws from one of Don’s own blog posts. Don ends his post with this claim

But it would have the huge advantage of spreading the social effects of controlling the inflation rate.

I disagree, quite strongly, with Don’s proposal, for a variety of practical and principled reasons, and would do even on a best-case model (say, legislation limited the extent of the Bank’s discretion and revenues were properly and formally ring-fenced).

(In the Herald article, ANZ chief economist Sharon Zollner is also quite sceptical, adding this tantalisingly radical observation – topic for another post another day:

She said the more salient questions we should be asking were not what tools should we use to try to steer the economy, but rather, should we try to do it at all, given the limitations of economic forecasting? Might the costs outweigh the benefits?

Don is quite right that (as we saw last year), petrol excise taxes can be adjusted very quickly and the effects are also typically seen in retail prices very quickly. He suggests that as the price elasticity of demand for petrol is quite limited, any increase in petrol taxes will quite quickly dampen households’ other spending, in turn dampening inflation pressures. There are certainly plenty of households who are quite cash-flow constrained, but whether the effect exists to a material extent in aggregate would need rather more careful and formal review (reflecting on my own behaviour, I’m also a bit sceptical).

But even if we grant that the effect is real and, whatever the effect actually is, perhaps fast-working, there are lots of other problems. These include:

- the temporary petrol excise tax cut of 2022/23 was 25 cents a litre. As far I can see, the direct fiscal costs of that were about $1 billion over 15 months. Even if it was $1 billion for a year, that is about 0.25 per cent of GDP. And although many economists, including me, pointed out that the income effect of this cut (and the associated road user charge and public transport subsidies) was inflationary, I’ve not seen anyone suggest it was a decisive factor in explaining core inflation outcomes over the last year or so. Quadruple the effect and one might be talking more serious macroeconomic impacts, but that would require giving the Reserve Bank discretion to make much larger changes in excise taxes than any Minister or Parliament has ever made before. Sold as an explicitly temporary effect, a cyclical stabilisation adjustment of this sort would probably result in less demand effects than, say, an excise tax increase known to be permanent.

- Don Brash argues that petrol excise taxes are easy to change. Much less so (as we saw last year in the rushed package) are road user changes for diesel-fuelled vehicles). The Brash scheme doesn’t seem to envisage adjusting road user charges, but to do one and not the other – as part of a new permanent stabilisation model – would seem simply politically untenable. He also recognises that electric vehicles are becoming more of an issue than they were when he first dreamed up the scheme, but says “Admittedly, with the growing use of electric vehicles there may come a time when varying the excise tax on petrol would have little effect on aggregate demand. But that time is still some way away.” It seems likely that EVs will soon, as they should, face road user charges, but again the politically tone-deaf nature of the suggestion that the unelected central bank should be able to whack on huge tax imposts on one lot of drivers but not others (the “others” often stylised as being upper income anyway) is staggering. And if you are tantalised by a thought “oh, but we can encourage people towards EVs”, remember that any such scheme would almost certainly have to be symmetrical…….

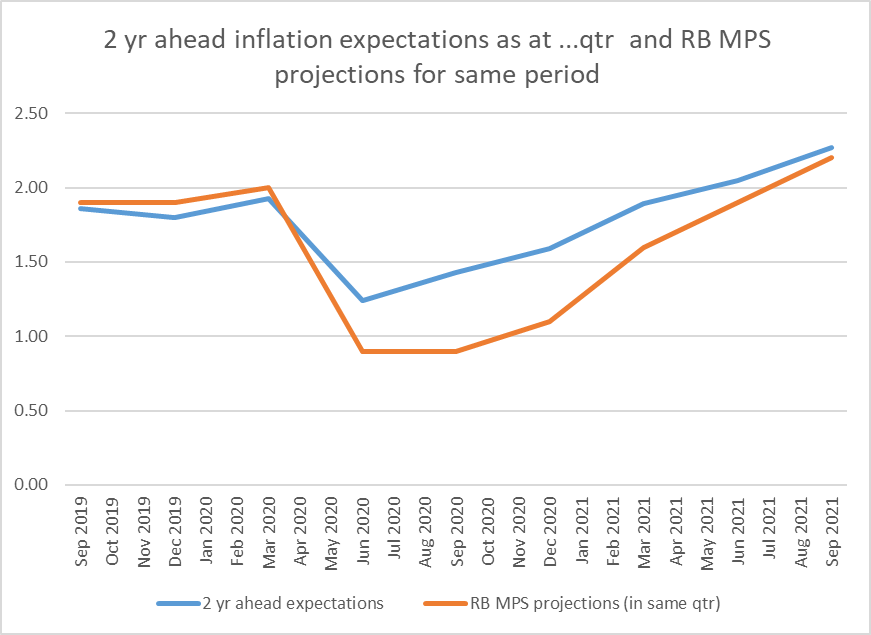

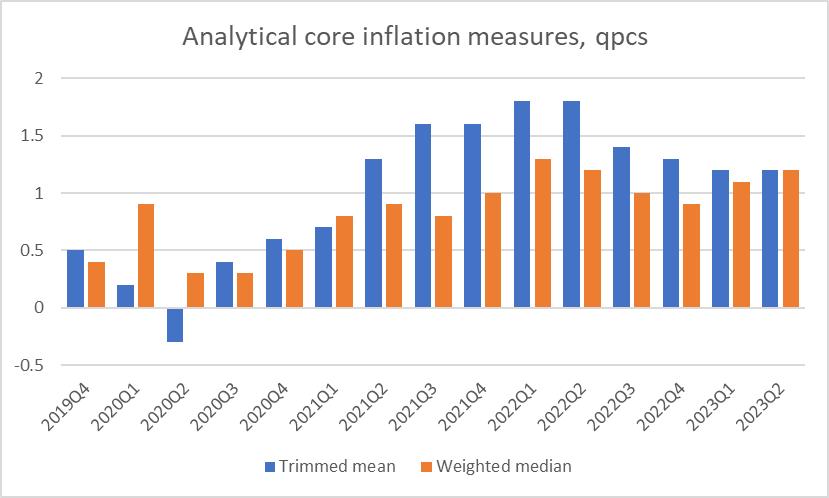

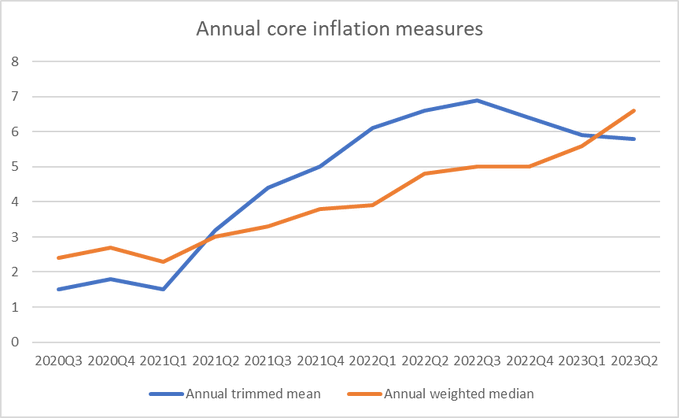

- As Brash acknowledges, one downside of his scheme is that increasing fuel excise taxes to fight inflation will itself, at least initially, boost CPI inflation. From a central bank accountability perspective this itself isn’t fatal (the target could be re-expressed as one for CPI inflation ex indirect taxes, and the fuel excise effect won’t show up directly in the better analytical core inflation measures), but…….one of the things we know about survey measures of inflation expectations is that they seem to be quite heavily influenced by headline CPI developments (and you can be sure media will keep highlighting headline effects). We don’t have a very good sense of how those expectations are then reflected in behaviour (spending, borrowing, price and wage setting) but it is unlikely to be helpful – and especially if we were talking of $1 a litre excise tax changes)

- It is certainly true that there are plenty of cash-flow constrained households. For better or worse, however, many of the most cash-flow constrained households also benefit from formal inflation adjustments (welfare benefit indexation), which directly undercut the cash-flow argument Brash is relying on. The tendency of governments to at least inflation-index the minimum wage works in the same direction (and if neither adjustment is immediate, the central bank should be focused on medium-term inflation prospects, not one quarter possible effects).

- People are rational. The MPC meets seven times a year. Given the prospect that seven times a year, on pre-announced dates, the fuel excise would be up for grabs, behaviour will change, with people either queuing for petrol the morning of the MPC meeting, or holding off as much as possible until just after. Especially if the prospective excise adjustments are large enough to be economically meaningful (and the road user side is even more challenging if it were to be included).

- It is a long-established principle of our system of government, dating back centuries, that taxes should only be imposed and adjusted by elected Parliaments (or at very least by formulae fixed by Parliament, as with indexation). Back when the Mortgage Interest Levy (see above) was being devised (I was the key RB deviser), I recall telling Alan Bollard that I would join the marches in the streets against any notion of taxation without representation. Same should go for petrol excise tax levies. It is all rather redolent of Muldoon’s proposal from the 1970s (which was firmly rejected) for the minister to be able to do modest adjustments to tax rates for cyclical stabilisation purposes. It is the sort of argument that has technocratic appeal, but no democratic appeal. And before anyone suggests parallels, the rate at which a central bank pays interest to a bank that chooses to deposit with it is not a tax.

- The Brash proposal seems to have no framework within which the MPC should decide whether to use a fuel excise tool, and to what extent it should use one tool rather than another. Perhaps overall accountability for inflation – weak as that now seems to be – would be unchanged, but we’d be opening the door to the whims of 7 unelected people, several with very little technical expertise either, to decide whether to whack up the fuel excise tax or whack up the OCR. There are huge distributional implications from such choices, and no framework. opening the way (among other things) to extensive lobbying from vested interests preferring one rather than the other. That seems, to put it politely, unappealing.

- One of the elements of the Mortgage Interest Levy proposal that exercised our minds a lot was how to ring-fence the revenue. There wasn’t much point in an additional tax, which might dampen some forms of demand, if the prospect of that money meant governments felt free to spend more. One can devise all sorts of clever-clogs institutional arrangements, but in the end public revenue is public revenue, net public debt is net public debt, and cost of living pressures and elections are very real. This might not be an insuperable obstacle, but money pots will tempt politicians (government and Opposition).

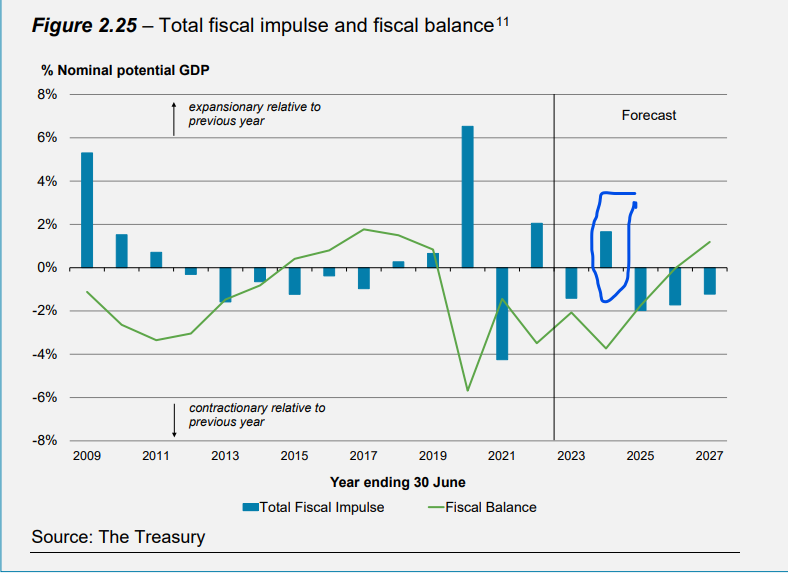

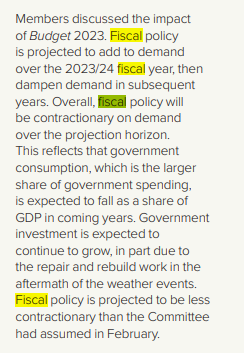

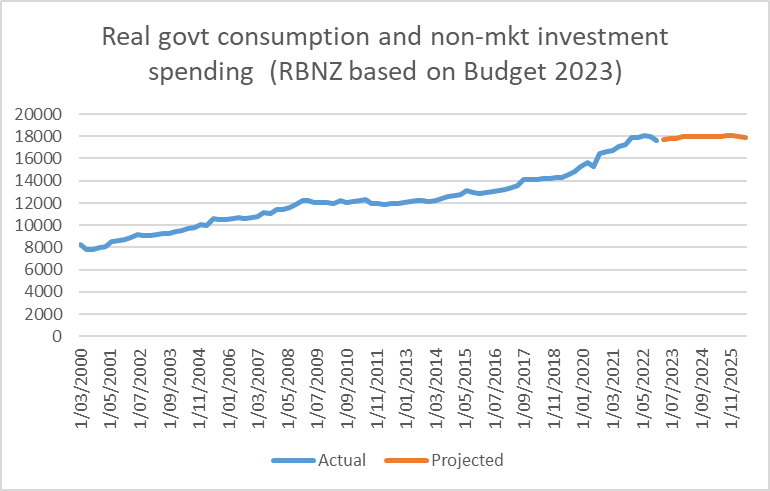

- Brash justifies his proposal on the grounds of mitigating the “social effects” of controlling inflation. That may well be a laudable goal, but it is one for governments. This year, however, the government has chosen to run a much bigger fiscal stimulus than it had planned even at the end of last year, on a scale swamping the plausible extent of any fuel excise tax tool, at a time when inflation is still a severe issue. Had they been at all concerned, there were options, within current legislative and governance frameworks. The government chose not to take them (and to a detached observer there is little concrete sign National would really have done much different).

Some of the points above matter more than others, and some will matter more to some than to others. But overall, it seems an unappealing proposal. Actually, I’d be rather surprised if the Reserve Bank itself were at all keen, at least after half an hour’s thought.

In the original Herald article a couple of weeks ago, the author ended this way

Quite.