Get me onto interwar economic history and I can get a little carried away. I don’t like to think quite how many books on the Great Depression – in all manner of countries – and events either side of it I bought when I first got fascinated by it, and my interest continues. New Zealand is a fascinating subset of that history/experience, although it is still the case that there is no single comprehensive economic, and economic policy, history for New Zealand in the interwar period, even though so much of interest/importance was going on.

Anyway, after yesterday’s post a reader kindly sent me a copy of a new NBER working paper by two prominent economic and monetary historians, Michael Bordo and Christopher Meissner. Their topic is “Original Sin and the Great Depression” – no nothing theological, but rather referring to the difficulty most countries long had (many still have) in borrowing externally in their own local currency. It is an interesting paper and they’ve used some fascinating high frequency data (by 1930s standards) in some of their estimates, but the key bit from my perspective was the question of how foreign currency debt might have influenced the willingness, or otherwise, of countries to devalue, or allow their currencies to depreciate, during the Great Depression. This has often been perceived to be an issue in more-recent decades: a currency depreciation greatly increases the local currency value of foreign currency debt, and if much of the debt (public or private) is (a) in foreign currency and (b) not supported by export industries, earning foreign currency, it can act as an obstacle to necessary adjustment. As it was in places in Latin America in the 1980s, so in places in east Asia in the 1990s.

Bordo and Meissner try to unpick whether this was a constraint on countries in the 1930s – a consideration that lead them to delay longer than otherwise the sort of break with gold and the exchange rate adjustment that ultimately looks to have been important in the eventual recovery. They find some suggestive evidence that this was so and that market pricing recognised the issue (thus, a higher risk premium was priced into the yields of countries that depreciated). They line up data, for example, on when countries defaulted (if they did) and when they went off the Gold Standard.

I wouldn’t be surprised if a more detailed examination of the issue proved that there was something to the thesis. But it probably needs a more -in-depth treatment to account for the huge variation in what exposure to exchange rate fluctuations actually meant across a wide range of countries. In some cases it is simple – a country with its own currency, but with much/most of its debt raised on market in foreign currency (whether sterling or USD). In other cases, it isn’t. For example, in the United States much debt – including most government debt – was denominated in USD, but also contained a gold clause – guaranteeing that the lender was protected against any exchange rate change (I only discovered yesterday that much Canadian debt also had such clauses). I wrote here about the recent book on the abrogation of the US gold clauses by Roosevelt. In effect, it was a sovereign default, and is treated as such by Bordo and Meissner). But Canada also overturned its gold clauses, and it isn’t treated as having defaulted. On the US side, public debt going into the Depression was low and I don’t recall ever reading that the gold clause had been a constraint on action prior to 1933.

Also, among advanced countries, war debts and reparations were at the time one of the most important form of inter-country liabilities, and although those obligations generally weren’t expressed in local currency terms, they also were generally not expected to be resolved through market mechanisms (and the debts were not traded, so there is no secondary market pricing). And although the authors claim to have dealt with these debts, almost all of which were eventually defaulted on (Finland was the exception that paid in full), their tables of countries which defaulted don’t line up well at all with what we know of the defaults on war debt. Thus, the UK defaulted on its war debt to the US (denominated in USD) and is (rightly) treated as a defaulter. But neither New Zealand nor Australia is listed as having defaulted, even though neither paid any more on their substantial war debts to the UK. (Both countries also “defaulted” on domestic debt – the New Zealand story is here.)

As a matter of interest, this table is from Eichengreen. The Hoover Moratorium was a standstill on servicing war debts and reparations in 1931, but the table captures annual savings/losses that became permanent over the following few years

In per capita terms, New Zealand was the second-biggest gainer (after only Germany) – we lost reparation payments due but saved a lot on the war debts we never again serviced (and which the UK never pursued us for).

But to an extent this is by way of rambly preamble to my New Zealand specific bugbear with the paper, which includes this table.

Not only did we default – domestically, and externally (those war debts) – but we were not on the Gold Standard. This is a not-infrequent mistake made by overseas academic researchers – Eichengreen, for example, has a table in which he has New Zealand leaving gold in 1929.

We did not. We had not been on the Gold Standard since World War One started in 1914 (as I wrote about in an early post here). We did not return to gold in 1925 when the UK returned. From August 1914 onwards, bank notes (issued by the trading banks) were not convertible into gold on demand, and banks were not required to keep any particular level of gold. There was no central bank, buying/selling gold at a fixed parity. We were not on the Gold Standard – even if that state of affairs was maintained by wartime regulations still in effect years later, rather than by a formal new statute.

In the, perhaps vain, hope of making a small contribution to putting a stake through the heart of this particular myth, here is an extract from Sir Otto Niemeyer’s report to the New Zealand government in February 1931. Niemeyer was a senior Bank of England official commissioned by the New Zealand government to visit New Zealand and to report on policy options re banking and currency, including around a proposed new central bank. Here are the opening two paragraphs of his report.

Banks held gold. The fact that they did so may have given some comfort to depositors. A solid loan book would generally do that too. But gold played no continuing part in the New Zealand monetary system after 1914. To repeat, after that date we were not on a Gold Standard.

Of course, quite what standard we were on is another matter. There was no central bank. In practice, as Sir Otto goes on to note – and as everyone recognised at the time – the key constraint on banks’ activities in New Zealand (lending) was the availability of sterling balances in London, combined with the customary practice – and it was no more – that banks managed things to keep New Zealand deposits exchangeable into sterling at very close to parity. In the jargon, there was no nominal anchor in the system – neither metallic, nor a central bank required to keep something akin to price stability. It was a very unusual system, that perhaps should not have worked, but it did more or less. Partly as a result there was little real sense – and I gather this was true in Australia as well – that a New Zealand pound (a pound liability issued by a bank in New Zealand) was in some sense different from an English pound.

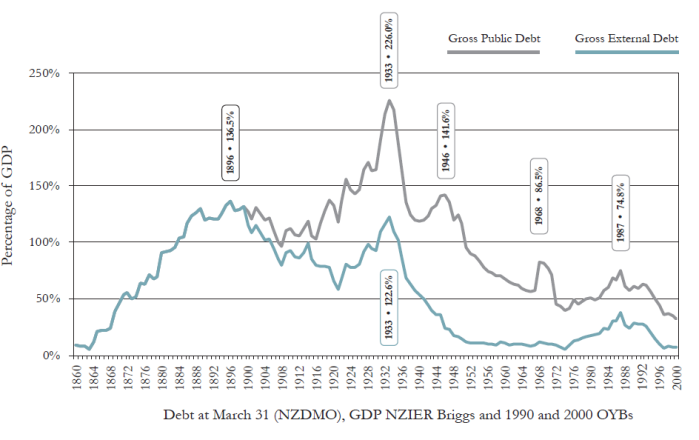

But to revert to the question of debt and the Depression, New Zealand’s government was heavily indebted going into the Depression and the debt ratios got much worse at the Depression went on. Here is total New Zealand government debt as a per cent of GDP from the IMF’s Historical Public Debt database.

and here is a chart from a paper Bryce Wilkinson did for the New Zealand Initiative a few years ago showing both public debt (slightly different series) and external debt as a per cent of GDP.

(Around this period the Australian charts are quite similar)

Bordo and Meissner include a chart suggesting that in 1928 our ratio of foreign public debt to exports – some sense of servicing capacity, and New Zealand was a big exporter at the time – was the fourth largest of the countries they study.

Curiously, and something I learned the other day from another new book, despite these astonishingly high levels of government debt (and heavy external debt) as the Depression began New Zealand had the highest possible credit rating from Moodys.

In a way, it worked out okay. We defaulted on the war debts, but for the sorts of public issues Moodys’ was rating, no foreign holder lost a penny (not even a (new) New Zealand penny let alone the (more valuable after 1933) UK penny). But it need not have been that way: the debt burden was punishingly high, markets were temporarily closed to any new issues, and by the end of the 1930s, New Zealand external finances were even more severely constrained, the possibility of default was in the wind.

To some extent, these public debt series overstated the burden on the taxpayer. Quite a bit of what the Crown borrowed was on-lent, particularly to farmers. On the other hand, farm debt was a pretty major area of difficulty during the Depression, with repeated interventions to ease the burden (on good farmers). New Zealand was heavily indebted – government and private (estimates of total mortgage debt as a per cent of GDP then exceed those now).

But if public debt was high going into the Depression it went higher, in two separate stage. First, the denominator – GDP – fell sharply. Nominal GDP in 1932 is estimated to have been a third lower than in 1929 – the fall split roughly evenly between quantities (real GDP) and prices. And then – and this is the link to Bordo and Meissner – the exchange rate was formally devalued at government initiative (even though there was not yet a government-issued currency) in January 1933. That raised the local currency value of the foreign debt – more so, at least initially, than it contributed to the recovery of nominal GDP. Government debt as a per cent of GDP peaked (on both charts) in 1933.

Devaluation had been an option debated for some considerable time. Most local economists were in favour, as (of course) were the farmers – the prospect of more local currency for each pound sterling earned was attractive to say the least. On the other hand, it was something others were more sceptical of – all such policy choices are distributional in nature. Importers and associated merchants were one group, but the trade unions were also wary – whatever you believed about the responsiveness of the economy over time, tradables prices (including food) seemed likely to rise. Of course, a rise in tradable prices was the whole point.

What is less clear is how much influence the additional debt service costs had on the Cabinet’s thinking. It was a real factor, at least in the short run. On the other hand, ministers will have been conscious that earning the foreign exchange to meet the foreign debt commitments was made a bit easier by the devaluation, and those sterling earnings were also critical influences on local banks’ ability to lend, and thus to support any prospects for recovery. The Bordo and Meissner paper does not seem to take this factor into account.

As I noted earlier, when the New Zealand government coercively restructured domestic debt (in effect, defaulted) they did not attempt the same on the government’s foreign debt. There are likely to have been a variety of factors at work, including a more generalised desire to have continued near-term access to UK markets (and New Zealand and Australia had both developed reputations as rather over-eager borrowers in the 1920s) and the little-known Colonial Stocks Acts (which I thank a commenter the other day for drawing my attention to again) under which the UK government had – with our consent – the authority to disallow specific legislation that disadvantaged holders of New Zealand debt in the UK. Whatever the combination of factors, the focus of the government’s efforts and rhetoric were instead on raising the world price level – lifting commodity prices generally, and those denominators (GDP). That made a lot of sense with so much excess capacity and such a fall in the price level. It was something Britain and the Dominions joined in committing to in the British Empire Currency Declaration of 1933.

As a final observation in this (discursive) post, when people talk at present about the fiscal costs of responding to the Covid-19 slump you sometimes hear talk of debt getting to “wartime levels”. People who used those references typically have places like the US and the UK in mind. As you see from the charts above, public debt kept dropping as a share of GDP through the rest of the 1930s – mostly rising GDP rather than falling debt – and even in 1946 New Zealand’s public debt, while high by today’s standards was about 148 per cent of GDP, lower than it had been in 1929. Between heavy taxes and Lend-Lease obligations the US ran up to us, the war wasn’t one that left us under a heavy burden of debt. At the end of it all, we’d built up enough unsustainable financial claims on Britain that a considerable chunk were, under pressure, written off. The UK, in effect, defaulted on us.