I’ve been championing the idea of thinking of what the government does now financially in terms of a national pandemic income insurance policy, of the sort we might have formally set up had we thought about it decades ago, but which also wouldn’t be inconsistent with the cautious way successive governments have run aggregate fiscal policy over the last 25-30 years. I used these two charts this morning responding to someone on Twitter

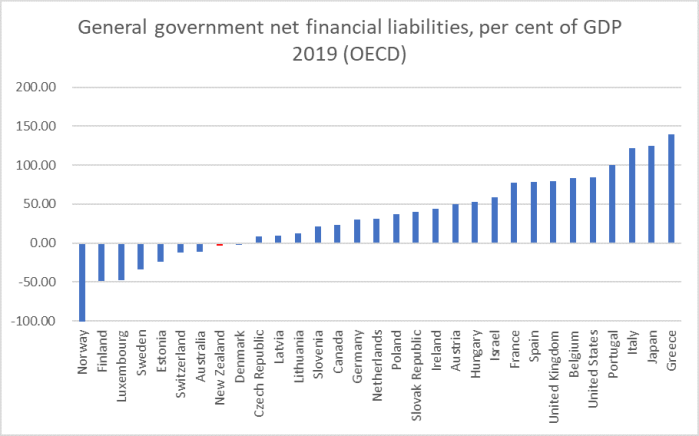

Consistently low net debt (basically zero on this broad, comparable, measure) and among that group of countries that has kept debt in check even in the wake of the last recession (and the earthquakes in our case).

I want to come back to my “80 per cent net income insurance” scheme for the first year later in the post, but before doing so I want to comment on a recent short paper from a group of academics at the University of Lausanne proposing an approach that seems very much in sympathy with the way I’ve been thinking about the issues, although different in form and, it appears, more open-ended in commitment.

Here is the brief abstract

Due to COVID-19, large parts of the world economy are being put on hold by government fiat. We argue that – on efficiency as well as equity grounds – the state should generously support not only labour but also capital costs, the latter through ex ante partially reimbursable, rapidly disbursed ‘corona loans’. The exact criteria for reimbursement can be determined ex post – depending primarily on the sector-level severity of lockdown-induced income shortfalls.

Of course, the dramatic slump in economic activity is only partly the result of government actions, but set that detail to one side for the moment.

They set out reasons why compensation should not be complete

While the state should bear the bulk of the coronavirus costs for workers and firms, we do not advocate 100% compensation. The main reason for this is that even in the current exceptional situation, certain moral hazard problems remain. For example, full wage replacement would eliminate the financial incentive to look for jobs in sectors that are expanding during the lockdown, for example in health care or logistics. Companies that could open up new areas of activity during the COVID crisis – think of restaurants that could offer home deliveries – would likewise have little incentive to do so. And, looking ahead to when the lockdown will be gradually eased, workers able and allowed to return to work should have an incentive to do so, while their quarantined peers should continue to receive financial support.

The loss of wages caused by the lockdown also means more (albeit constrained) leisure time and cost savings (e.g. for external childcare), which can justify a certain reduction in income.

To which, perhaps, one could add that with shops etc closed, consumption options are constrained anyway.

In most countries, there isn’t a great deal of controversy about supporting workers, although there is ongoing debate around the extent of such support (in New Zealand, that support is relatively modest, and in a scheme that currently expires in June). The really contentious bit of any far-reaching proposals is what to do about capital income. These authors address that directly

Unlike actions taken by most countries to bridge wage outlays, policy responses with regard to capital costs (rent, maintenance costs, storage costs, depreciation, interest, etc.) are much more limited. Fixed non-wage outlays can account for significant shares of the costs of small and medium-sized companies. So far, around the globe, only repayable loans have been made available for this purpose. The implicit public compensation here is therefore very close to zero. This is neither efficient nor fair.

The inefficiency of a pure loan policy is due to the fact that a repayable loan equivalent to several weeks’ or even months’ turnover is likely to be a major burden for many firms. Companies with tight margins and thin capital cushions may well be forced to file for bankruptcy in the face of such a debt burden. This phenomenon would affect an increasing number of companies as the lockdown drags on. In view of the high external costs of a wave of bankruptcies, zero compensation of the cost of capital is therefore inefficient from a macroeconomic perspective.

Pure loan policies can also be questioned from an equity perspective: Why should the owners of affected companies have to bear the loss of income themselves? They are no more or less to blame for the crisis than owners of businesses that happen not to be affected by this uninsurable once-in-a-century event (e.g. food retailers or certain IT companies). The insurance logic outlined above therefore also applies not only to labour but also to capital.

As I’ve argued here, loans might have a place for some firms, but for most they are no sustainable solution. The Lausanne authors suggest using loans that might later by written off by the state.

What might a practicable solution look like? Again, efficiency considerations do not speak in favour of 100% public compensation of revenue shortfalls due to the crisis. Companies that still have a certain sales potential during the lockdown should not have an incentive to halt all activity and rely fully on state support. In addition, companies that are already ailing should not be kept afloat artificially.

An efficient and fair compensation of capital costs of affected companies should therefore be in the same percentage range as the wage replacement measures, i.e. up to 80%. The compensation rate could be set higher or lower depending on the duration of the lockdown and the severity of the turnover foregone. Such compensation could initially take the form loans issued by commercial banks, as is currently the case in many countries. However, the particularity of ‘corona loans’ would arise from an announcement from the outset that they will be not only backed by a state guarantee but also accompanied with a promise that in the future a portion of the loan (up to 80%) would not have to be paid back, being covered by the public purse instead. The precise discount would be determined after the crisis, depending on the duration of the lockdown, on the severity of the impact on different sectors, and on individual companies’ cost structure. There would be sufficient time for such an examination after the crisis (as opposed to immediately, before granting any bridging loans).

And they offer some thoughts on what write-off conditionality might look like

What could a workable rule for ‘corona loans’ look like? Non-repayable grants could be reserved for sectors that cannot, or only to a very limited extent, make up for lost revenue during the lockdown by deferred demand – think of the catering, personal services or florists. Other sectors, such as furniture stores or construction companies, have a greater potential to catch up on lost sales after the crisis, which means that profit-contingent or even fully repayable loans would be more appropriate. It would be important to develop and publish such sector-specific criteria as quickly as possible in order to keep the financial uncertainty of the borrowing companies to a minimum. Clear criteria for transforming loans into grants should be published in advance also in order to avoid arbitrariness in making the final rulings firm-by-firm once the crisis is over. For the scheme not to be open to manipulation by firms or bureaucracies, these criteria should depend on industry-wide measures of corona-affectedness and on firm-specific characteristics that pre-date the onset of the crisis (i.e. taken from 2019 tax filings). The interest rate on such loans should be kept so low as to just cover banks’ additional administrative costs.

As an approach, it seems a great deal better than nothing, or than the sort of case-by-case probably-not-very-generous support to favoured large high profile firms that get the ear of the government that seems to be our government’s current default option.

But without some pretty clear rules upfront, these sorts of loans – that might or might not be written off, no one knows, and politics inevitably playing a part ex post – might help with immediate cashflow (not a trivial consideration of course) but actually offer very little in term of a buffer owners and operators can count on, or (relatedly) of certainty. The proposed loans also seem strongly skewed towards a presumption that the economy should just pick up again where it left off, but that also isn’t likely to make a great deal of sense, particularly (for example) in a country where a major industry – tourism – may be very slow to recover fully. It is also going to involve a huge amount of bureaucratic/political judgement about different types of firms that, in the end, isn’t likely to be terribly robust, even if in the end lots of money is paid out.

The conceptual simplicity – and, relatively speaking, the practical simplicity – of what I’m proposing is why I continue to think the 80 per cent pandemic income protection insurance approach, for firms and households, is the cleanest and simplest, and fairest, way to conceptualise how governments should be responding. I think it probably has superior efficiency characteristics to what the Lausanne authors are proposing, because it leaves entirely with the owners the choice about whether and when (subject to lockdown etc rules) to reopen or continue in business.

As a reminder of what I’m championing, here is a summary from an earlier post.

Recall the key dimensions from a couple of earlier posts:

- Parliament would legislate urgently (preferably, or the guarantee powers in the Public Finance Act would be used) to guarantee that every tax-resident firm and individual in the coming year would have net income at least 80 per cent of their net taxable income in the previous year (loosely the 2019/20 and 2020/21 tax years, but of course the slump will already have been serious this month),

- the guarantee would be restricted to a single year (Parliament and the Minister can’t bind themselves not to extend, but the framing would be a one-year commitment),

- it is a no-fault no-favourites approach. My taxes have to prop up Sky City just as yours will have to support people/firms you really can’t stand. Picking favourites is a recipe for corroding trust and the willingness of the public to see the public purse used responsibly to get us through the next few years,

- since the guarantee would be legally binding, and structured to be assignable, financial institutions should generally be willing to extend credit on the security of the guarantee (they don’t need the cash upfront, just the assurance that the Crown can’t really walk away). This is primarily relevant to businesses, given the ‘mortgage holiday’ banks have already agreed,

- the guarantee need not displace actual immediate income support measures, designed to get cash in the pockets of households now (rather any such state payments would be factored in when everything was squared up at the time of next year’s tax return), but especially if you are in lockdown and any mortgage commitments are deferred, high levels of immediate cash are less an issue than usual (not much to spend cash on).

- for firms, the guarantee would not be conditioned on any commitment to stay in business. In you are a heavily indebted tour operator in Rotorua and you think it will be three years until “normality” returns, walking away (closing down) now may well make a lot of sense. The 80 per cent guarantee for one year is simply a buffer, that limits the downside for the first year, and buys some time both for the business(owners) and their financiers. For some, however, it will be enough to give them time, and access to credit, to get their firm to a scale best suited to being able to come back. But that needs to be their judgement, and that of financiers, not a template imposed from Wellington.

- for individuals, the income guarantee will also help to underpin public support/tolerance for whatever restrictions remain in place for an extended period. …

- there might be merit, fiscally and from a fairness perspective, in considering supplementing the downside guarantee with a one-year special additional tax on any 2020/2021 earnings more than 120 per cent of the previous year (there wouldn’t be much revenue in it, and it plays no stabilisation role, but there might be an appealing political/social symmetry).

Note that such an approach would embrace – rather than be in addition to – all existing assistance, notably the income support through the wage subsidy scheme and the benefit system. The residual amounts due to households and firms would be paid out at the end of the 2020/21 tax year.

I had a good discussion yesterday with a smart person who posed a number of questions and challenges, some of which I’d thought about and others not (I’ve always envisaged that if any officials or politicians wanted to take the idea seriously, there would need to be some intense work done quickly by officials etc to flesh out the operating details).

One obvious question is what about cashflow? It is all very well to pledge, by statute, a payout, but cash now also matters for many (not all of course). As I’ve previously noted, for most households it is unlikely that a higher immediate cashflow is particularly pressing: there is a mortgage payments deferral scheme from the banks, there is the wage subsidy for now for many, and with so much closed there are relatively few options for many to spend much money on. In principle, an iron-clad guarantee from the Crown should be something people can borrow on the security of. But, in addition, and as I noted in the earlier post

I quite liked the idea the New Zealand Initiative put forward the other day (of allowing people to borrow – capped amounts – directly from the Crown, akin to a student loan, with income-contingent future repayments) and also like Michael Littlewood’s proposal – akin to what has already been done in Australia – of allowing people easy access to a capped portion of their Kiwisaver funds, it being after all their own money, and times being very tough. (KiwiSaver and COVID Littlewood)

The New Zealand Initiative proposal dovetails nicely with what I’m proposing here – immediate access to cash, and ability to repay once the squaring up occurs next year.

And what about businesses? Well, the government and banks have already launched a business loans guarantee scheme, in which the government guarantees 80 per cent of the risk. With an income guarantee of the sort I’m proposing, banks will be somewhat more willing to advance cash now against the security of the guarantee. Perhaps as importantly, more firms/owners will be willing to take on more debt, knowing that it is really just bridging finance pending the arrival of the grant (the “income insurance” payout).

What about the expense? I also touched on that in the earlier post

Since I only propose guaranteeing 80 per cent of the previous year’s net income, it is only if aggregate GDP drops by more than 20 per cent for the full year that the numbers start getting large at all (there will be expense well before that because many people – notably public servants, and those in some “essential industries” – will face no hit to wages or profits, while others are already experiencing huge losses). Suppose that full-year GDP fell by even 30 per cent – larger than any guesstimate I’ve seen, although who knows what next week will bring- and you still looking at an overall fiscal cost that should be no more than perhaps 20 per cent of GDP. That simply isn’t an unbearable burden for a country that had net general government financial liabilities last year (OECD measure) of 0 per cent of GDP (no, no typo there, zero).

A 30 per cent annual GDP loss is starting to look a bit closer to a central estimate at present, but I’ve still seen no full year estimates larger than that.

Now perhaps it is too simple to think in terms of a 20 per cent of GDP payout, and glibly assert that from our starting point (see chart above) that is readily affordable. The deterioration in the Crown’s fiscal position is not limited to whatever is paid out now or in the next year. In thinking about fiscal policy options presumably the government also needs to factor in the likelihood that this time next year not only will outgoings be running ahead of normal (all those extra unemployed) but, more significantly, tax revenue will be well below normal. And there will be who knows what pressure for more structural increases in government spending, every person and their dog championing their own “solution” for recovery.

Of course, depending on the situation with the virus, there might be a clamour for an extension of the income insurance into a second year. That latter probably should not be a major issue – not only could only further income insurance be set at a lower multiple (perhaps 60 per cent) it could also be set relative to the lower of 2019/20 and 2020/21 years (the latter only protected to 80 per cent). And, more importantly, unless somehow we believe this thing goes on forever, the likelihood of any very large expenditure in the second year has to be quite modest.

Frankly, this approach is both affordable and fair and something like it should be done now, when it offers some real underpinnings for people in a time of extreme uncertainty. But it is certainly true that fiscal policy after the crisis is going to be under a great deal of pressure – some of it from voters who are likely to demand an early end to perceived “largesse”.

There are all sorts of fine operational details (including trying to limit potential for rorting) to be worked out if something like this scheme was to be adopted. For households, the issues seem unlikely to be overly complex, given how little discretion most households have over their taxable income position. For firms, and especially multinationals, there may be more significant risks, and significant sums will be at stake for some of our larger firms. One obvious protection might be to limit the payout to any firm not just to 80 per cent of the previous year’s net profit, but also subject to a constraint that the payout could not be larger than 80 per cent of the previous year’s total gross expenses (to further limit scope for expenses abroad to be channelled through the books of the New Zealand resident entity).

The final issue I wanted to touch on here is about incentives. One way of looking at the 80 per cent income guarantee for this year is that it establishes an effective marginal tax rate, for firms and households, of 80 per cent (at least up to the point where market income is itself 80 per cent of last year’s). Marginal tax rates often influence behaviour.

At a household level, I’d be surprised if there were much of an issue here. In principle, establishing the guarantee might prompt some people to resign their job content to know they could collect 80 per cent of their previous year’s income. There would be a high risk of that happening in normal circumstances with something approaching full employment. But for most, walking away from a job would seem a rather rash step to take in the current climate, where the insurance is on offer for only one year, and yet the labour market a year out could still be very tough. If need be, perhaps one could supplement the rules with a provision reducing the guarantee for anyone who voluntarily left a job without another to go to. If one were worried about new entrants to the labour market (young people) being more than usually prone to such an approach, the guarantee could be set at a lower proportion for those under, say, 25.

What about firms? Here the risk is not that firms choose to shutdown operations knowing that they can collect the income guarantee anyway. Few firms that want to be around when the recovery comes will want to shutdown now any more than absolutely necesssary – you lose contact with customers (who go elsewhere), staff, and so on. I guess there is a reduced incentive to aggressively cut back on costs……but that would seem to be a feature not a bug. Everyone’s scheme or proposals are designed to help provide some sort of the bridge to the future, including by maintaining relationships with staff, as well as providers of other services (be it landlords, insurance providers, other professional advisers or whatever). So, yes, it will probably affect firm behaviour, but mostly in ways that are generally thought desirable, including providing that underpinning that might make firms more willing to play for time for a while – with a one year income buffer – rather than close precipitately.

Oh, and relative to many other schemes – including the Lausanne one – there is no distinction by type of firm, and all the judgements about what to do going forward rest with firms and their owners/managers, not on lobbying for favours or special deals, or any other sort of bureaucratic whim or vision of the new economy that will eventually emerge from the wreckage at present.

I’ll leave it there for now. I reckon the scheme has a great deal going for it, on both fairness and efficiency grounds. In a New Zealand context, it has the great merit of being a scheme that takes seriously the wider situation facing the mass of New Zealand businesses. Nothing the government – or the Reserve Bank, simply refusing to cut interest rates – has said or done so far yet comes close to addressing those issues. Perhaps they just don’t understand, perhaps they have poor advisers (quite likely, given RB and Treasury weakness), perhaps there is some tribal left-wing reluctance to be seen helping owners of capital. Whatever the explanation, the passivity is costing more and more economic activity, and firms, by the week.