In yesterday’s Sunday Star-Times another article by their reporter Kate MacNamara shed further light on just how unsuited Adrian Orr is to be Governor of the Reserve Bank, exercising huge public policy and regulatory power still (in large chunks of the Bank’s responsibilities, often with crisis dimensions to them) as sole decisionmaker, with few/no effective checks and balances. These disclosures should also raise serious questions about the judgement and diligence of the Board who were primarily responsible for Orr’s appointment and are primarily responsible for holding him to account, and of the Minister of Finance who formally appointed Orr, and is responsible now for both him and for the Board.

In this latest in her series of articles, MacNamara draws on the responses to one of several Official Information Act requests she had lodged late last year. She had sought from the Bank copies of communications between the Governor and (a) the head of the financial sector body INFINZ and (b) Roger Beaumont the executive director of the Bankers’ Association (those responses are here), and copies of communications between Orr and the New Zealand Initiative think-tank, especially its chair Roger Partridge (responses here). Her article draws mainly on the response re the New Zealand Initiative.

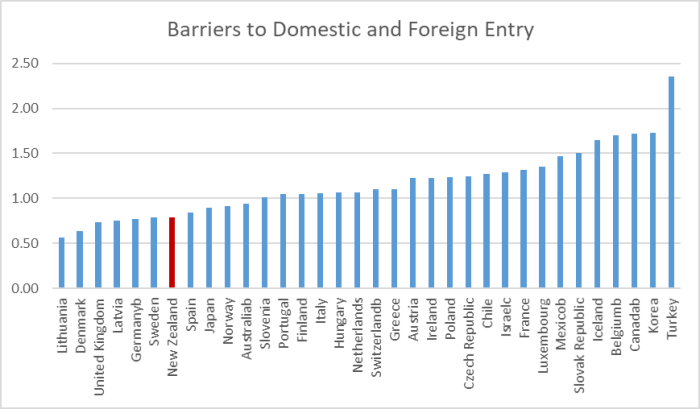

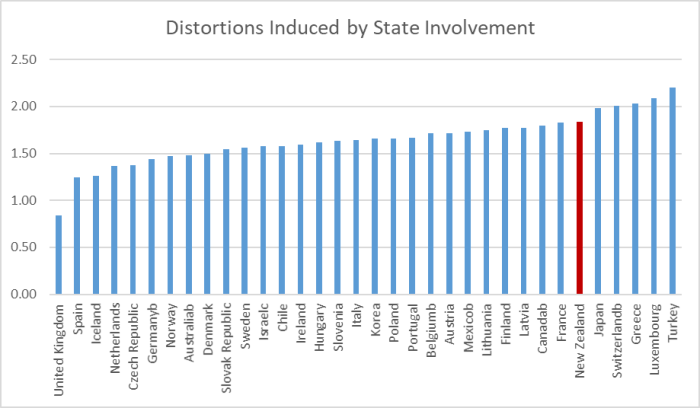

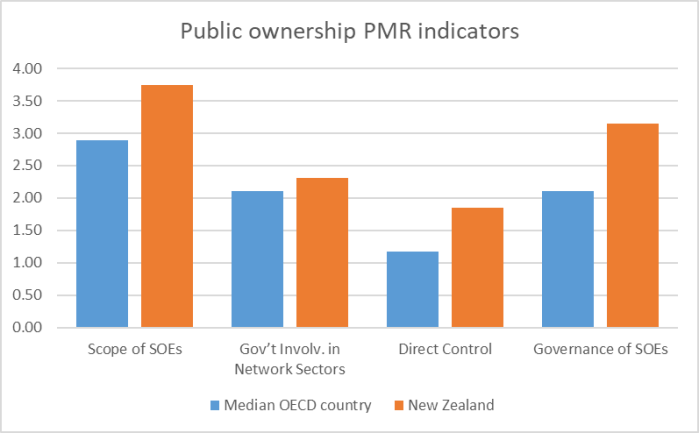

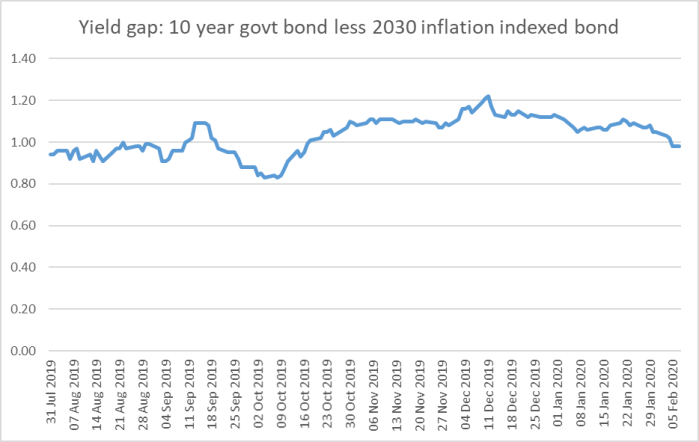

The context here is Orr’s (then) proposal to dramatically increase the volume of capital locally-incorporated banks would have to have to fund their existing loan books in New Zealand, disclosed in December 2018. A wide range of commentators locally were critical of the Bank and many drew attention to the rather threadbare nature (at least initially) of the supporting material (it took three waves of releases over several months before we finally got the full extent of the Bank’s – still-underwhelming – case). There had been no technical work preparing the ground, even though Orr was to be prosecutor and judge in his own case. There was no serious cost-benefit analysis for what Orr was proposing, no serious benchmarking against capital requirements in other countries (notably Australia), no serious analysis of the nature of financial crises, and a strong sense that Orr wanted to compel us to pay for an insurance policy that simply wasn’t worth the price. All this from an organisation where a recent careful stakeholder survey – conducted by the New Zealand Initiative before Orr took office – had highlighted very serious concerns about the Bank’s financial regulatory functions. Meanwhile, Orr was already underway with his open attempts to cast anyone who disagreed with him as a “vested interest”, somehow “bought and paid for”.

Various people made public comments. Among them was Roger Partridge, chair of the New Zealand Initiative, who had a column in NBR in early May critical of what was being proposed, and the processes used (at the time the Initiative was finalising its submission to the formal Bank consultation). In my contact with Roger, he always seems much more interested in the substance and process of any issue. But in a single decisionmaker model, it is a single person in focus. [UPDATE: Here is a link to the “offending” column.]

Anyway, the Governor did not like Roger’s column at all. Normal people who disagree might either let things wash over them (being in public life, exercising great power, not only does but should, bring scrutiny, challenge, and criticism). Or perhaps you might even ring the author and have an amiable chat. But not Orr.

The OIA release begins with Partridge emailing Orr after learning that Orr had rung the Executive Director of the Initiative had been “upset” by Partridge’s column. This is a bit of a problem for the Initiative, as Orr is scheduled to speak at a private lunch for their members the next day, so Partridge offers up one of those semi-apologies (“if I crossed the line I apologise, but don’t resile from the criticisms of the policy process”), and even goes so far as to send Orr a copy of the remarks he intends to use to introduce Orr the next day (typical gush).

But that is not nearly enough for our thin-skinned Governor who replies to Partridge with a page and a half email. All this after Orr had already talked to Hartwich both before and after a flight to Auckland they had both been on. Just a slight loss of perspective and focus you might wonder?

And so we read (of his conversation with Hartwich)

I talked of the personal abuse I receive in this role. I also talked of the vested-interest driven articles that are prevalent and portrayed as analysis.

and

I do not accept your apology as it provides no reflection on your:

1. Stating I have a gambling problem.

2. Mocking our use of a Maori mythology to connect with a wider NZ audience – something we have been tasked by the public and stakeholders to do (I noted to Oliver this is a common thread of online abuse I receive from other purported banking/economic experts that go even further in ethnic/religious/personal comment).

3. Claiming below that you aimed to provide a robust critique of the proposal. You do not. You quote selective work of purported experts. You also pull only selected components of our submission process (which has stretched nearly 2 years).

From context, I understand that Partridge had said something along the lines that Orr was doing little more than gambling with his ill-supported capital proposal. If so that seemed (and seems) fair to me, and would not to any reasonable person, with any sense of perspective, suggest they thought the Governor had a gambling problem.

I guess we are expected to just believe the lines about “online abuse” (and, who knows, perhaps I’m one of the people he is alluding to).

It goes on, before ending this weird way

I do not see your article as a robust critique. What I do see is ongoing character assassination, an undertone of dislike of the RBNZ, and a clear bias in economic and ethnic preference.

At the Bank we are open minded and working on behalf of all New Zealand and do so in a transparent manner.

See you tomorrow. The introduction looks fine. I will be professional and courteous towards your members.

Adrian

The person

But, of course, he is calm, open-minded, and – apparently unlike any of his critics – only focused on the national interest. And what to make of that “The person”? If any upset junior staffer sent such an email to his/her boss, you might seek to get them some support and counselling. But this was the most powerful unelected person in New Zealand, responding to a private citizen who happened to disagree with him.

(Of course, I can well understand why they didn’t do so, but in some respects it is a shame the Initiative didn’t disclose this correspondence at the time, so poorly does it reflect on a leading public official, making major policy decisions while clearly not coping. I hope at least they referred the matter to the Minister and the chair of the Bank’s Board.)

Partridge sent another placatory email to the Governor, only to get yet another page-long missive

The behaviours displayed by your institution make it appear that it is a low chance that a well informed discussion where all parties come out better off could be ever achieved. We Remain open minded.

ending

See you later today. I will be professional and respect your members. I do not gamble.

There had been no mention of the “gambling” thing in Partridge’s email Orr was here replying to.

The rest of that OIA release is fairly uncontroversial stuff from 2018 on the release of the Initiative’s report that dealt with the Bank’s financial regulatory functions (the one the Governor claimed at the time to take seriously and welcome, although also the one he was rubbishing by late last year.)

What about the other OIAs? It is mostly less egregious stuff. But we have this odd example from a letter to the Executive Direction of INFINZ on 24 May 2019

For closure sake as promised, I mentioned to you at the event that I was disappointed with the process that you adopted in the preparation of a submission to our bank capital proposals. I did so as I want to be open and frank consistent with the ‘relationship charter’ we recently established with our regulated banks I read about your views first in your published op-ed and then via a newsletter you sent to INFINZ members. It was some time after that you met with RBNZ staff. The process created a perception of a predetermined outcome for the submission.

How shocking. A private sector industry group first published its views in an op-ed and a newsletter and didn’t first talk to RB staff. Quite who does the Governor think he is in objecting to that?

Even odder was this

In the spirit of the ‘#me too’ commentary promoted at your awards evening, I have received personal written and verbal abuse from within the industry during this consultation process. For New Zealand’s capital markets to have the ‘social license’ to operate – another theme at your event – I believe the industry’s culture needs ongoing improvement.

As a reminder to the Governor, we don’t have lese-majeste laws in New Zealand, and certainly not for central bank Governors. And as for this weird appropriation of the “#me too” movement – mostly about the mistreatment of women by men in positions of power over them – to apply to criticisms of a very powerful public figure…..well, weird is just the best term for it.

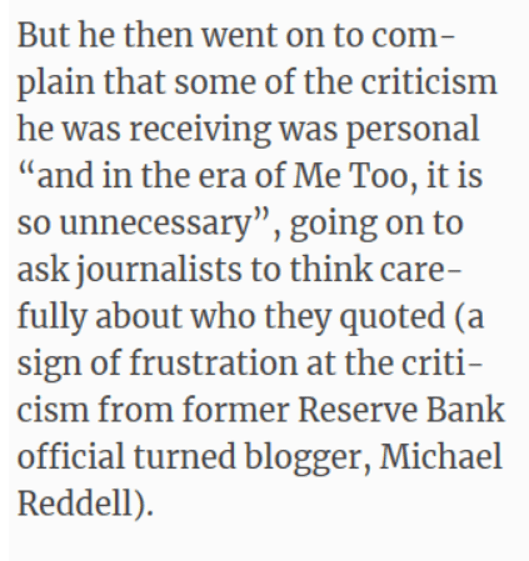

It wasn’t the only time he’d tried this line. In a column late last year, Hamish Rutherford told us he’d even used it at a parliamentary committee

Being in position of power, Orr’s complaints brought forward this response from the INFINZ Executive Director

We are concerned and disappointed that you have received verbal and written abuse from within the industry during the consultation process – bullying is not acceptable and we agree that all discussions should be both professional and respectful.

Quite how anyone in the industry – or anywhere else for that matter – could have “bullied” the Governor (who single-handedly wields all the power that mattered on the bank capital issues) is beyond me, but I guess INFINZ didn’t want to jeopardise their ability to get the Governor as a speaker etc.

The final set of OIA responses cover the Executive Director of the Banker’s Association.

The first was a Saturday morning email to Beaumont and the chairs of the four main banks in April. It isn’t offensive and thin-skinned as he later became, but while the submissions are still open, he is clearly trying to put pressure on them

FYI only as I am eager you understand the effort we are going to in order that the Bank is open and listening.

This was not the impression you all conveyed to me over the last couple of weeks in our individual one-to-one meetings.

Only there is nothing in the rest of the letter to give anyone any reassurance.

In late May there is a letter (presumably emailed) from Beaumont to the Governor, copied to the Minister of Finance, about the “independent experts” the Governor had selected to help make his case. The letter isn’t aggressive in tone but noted that none of the independent experts had New Zealand specific knowledge and suggest a couple of locals they could work with.

But this sparks a petulant email back from Orr, also copied to Grant Robertson

Dear Roger,

Your letter is unsigned. Can you confirm it is legitimate please? Apologies, one must be careful.

and

I do not understand the reason you have copied the Minister of Finance in to this dialogue. Is there something specific you are looking for from the Minister’s office that I need to understand?

Minister of Finance? Well, you mean the elected person with overall responsibility for economic policy, the person who has formal responsibility for your performance etc etc?

Recall, that all the stuff covered in the material that came to light yesterday is really just another glimpse at what was apparently a pattern of quite inappropriate behaviour. From one of Kate MacNamara’s earlier articles

But other observers were not surprised. Details of [Victoria banking academic Martien] Lubberink’s experience were already circulating in Wellington and industry sources say they match a pattern of hectoring by Orr of those who question the Reserve Bank’s plan.

“There is a pattern of [Orr] publicly belittling and berating people who disagree with him, at conferences, on the sidelines of financial industry events,” said one source who’s been involved in making submissions to the Reserve Bank on the capital proposal.

There have also been angry weekend phone calls made by Orr to submitters he doesn’t agree with.

“I’m worried about what he’s doing.”

The source said some companies have “withheld submissions,” for fear of being targeted by Orr.

“They’re absolutely scared of repercussions. It’s genuinely disturbing,” he said.

We can only wonder what he was like inside the Bank or around his own Board table.

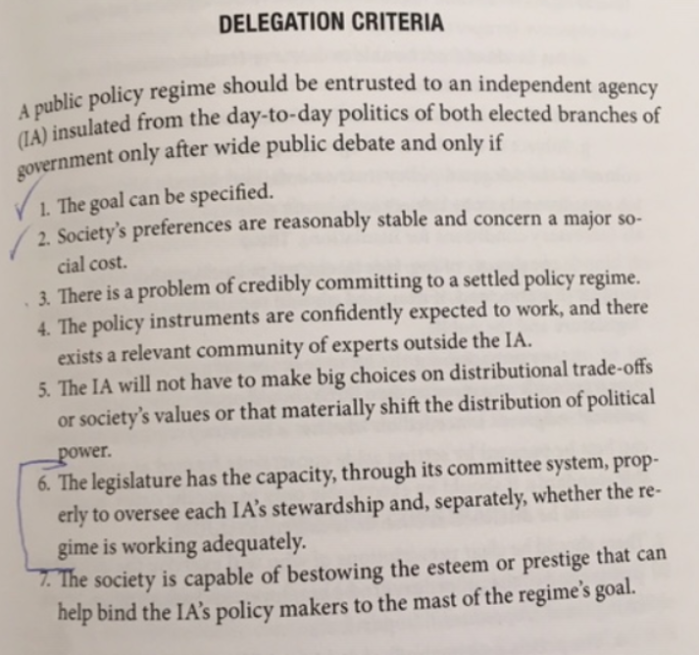

Does any of it matter, or is this simply the degraded state of public life we now have to get used to? Age of Trump, age of Orr etc.

It should be utterly unacceptable, in any public figure, but perhaps especially so when that one public figure is (a) unelected, and (b) wields such huge discretionary power on far-reaching policy matters, with few/no checks and balances. I was tempted to suggest that the individuals in receipt of these particular Orr missives are big enough to stand up for themselves, except that evidently they aren’t really – Partridge, Hartwich, and McElwain find themselves rushing around the placate Orr. That’s costly and uncomfortable: much easier just to pull your punches and offer less challenge or scrutiny next time the bully (for on his revealed behaviour it is him not his critics who better fits that description) wants to push through some half-baked costly idea.

The banks themselves will long since have gotten the message – it was Orr’s predecessor who heavied the BNZ to shutdown Stephen Toplis when he wrote a critical commentary on some aspect of Wheeler’s monetary policy – but the experience last year will only have reinforced that extreme caution. Recall that Orr wields direct power over them in all sorts of way, visible and less so, and clearly does not cope with being challenged or criticised (no matter how many times he claims to be “open-minded”. It is great that Kate MacNamara has kept up the scrutiny, but that will presumably mean no access: much easier for her fellow journalists to keep their heads down and not ask hard questions of the Governor and Bank (who – news though it may be – are not infallible).

And what about people inside the organisation? Recall that on regulatory matters the Governor is still the sole decisionmaker, and on monetary policy he has – in effect – most of the clout, all of voice, and no real transparency. It is vital that the Governor’s priors, whims, and even well-considered ideas are seriously scrutinised – and even that the Bank sticks to its statutory roles – but seeing the Governor treats outsiders, how are people inside the Reserve Bank likely to respond. All but the most brave or reckless will be strongly incentivised to keep quiet, go along, join the cheerleaders etc. In any public agency that should be grossly unacceptable, but particularly so in one as powerful as the Bank. Orr has grossly abused his office, and looks increasingly unfit to hold it.

And if Orr gets away with it what message does it send to other thin-skinned bullies elsewhere in the upper ranks for our public sector, let alone to those who work for them.

And yet it looks as lot like Orr will get away with it. Perhaps there was some quiet word in the hallowed halls of the Bank’s Board room, but these are the same people who selected the Governor less than two years previously. They are invested in his success, and they and their predecessors have a long track record of providing cover and defence for the Governor, not serious scrutiny and accountability on behalf of the public. This behaviour occurred in 2018/19 and there is no hint of concern in the Board’s published Annual Report.

If any of this bothered Grant Robertson, it can’t have been much. You’ll recall that response I had late last year from Robertson, when I wrote to highlight his formal responsibilities for the egregious conduct highlighted in earlier MacNamara articles. He then expressed his full confidence in the Board and suggested he was satisfied with the Governor too. In the great tradition of “lets look after each other” Robertson has just appointed the Board chairman to a further two year term, even as he walked by such appalling conduct by the person he is paid to oversee.

(It is sad to reflect that much of the material covered here relates to events in May 2019. That was the same month the then Secretary to the Treasury was also going rogue, grossly mishandling – and then refusing to apologise for – his handling of the “Budget leak” episode. Doesn’t exactly instill confidence in the top tier of our leading economic agencies – or the Minister responsible for both – does it?)

Perhaps it is all in the past now. Perhaps having got through the year, made his final decisions etc, Orr has returned to some sort of stable equilibrium and is operating effectively, rigorously, and deeply to provide leadership in difficult times. Perhaps. But even if that were so – and that sort of Orr was not on display last Wednesday – no one who can lose all perspective as badly as Orr clearly did last year, who simply cannot cope with serious criticism and scrutiny, simply should not hold high office here or anywhere else. It is risky for New Zealand, it is dreadful for the reputation of the Bank, bad for the reputation of the New Zealand public sector, and reflects pretty poorly on our political leaders – in government and Opposition – who simply walk by, at least in public, such egregiously unacceptable conduct from such a powerful public servant (one who doesn’t even have the redeeming quality of being consistently rigorous, excellent and right to perhaps compensate in some small measure for his grossly unacceptable).