Here is a chart of current 10 year (nominal) government bond yields for a selection of advanced economies

The median yield across those bonds/countries is about 0.4 per cent. For two of the three largest economies, long-term yields are negative. Only Greece – which defaulted (or had its debt written down) only a few years ago and still has a huge load of debt – is yielding (just over) 2 per cent, closely followed by highly-indebted Italy, which could be the epicentre of the next euro-area crisis.

Of course, you can still find higher (nominal) yields in other countries – on the table I drew these yields from, Brazil, Mexico and India were each around 7 per cent – but for your typical advanced country, nominal interest rates are now very low. One could show a similar chart for policy rates: the US policy rate is around 2 per cent, but that is now materially higher than the policy rates applying in every other country on the chart.

For a long time there was a narrative – perhaps especially relevant in New Zealand – about lower interest rates being some sort of return to more normal levels. Plenty of people can still remember the (brief) period in the late 1980s when term deposit rates were 18 per cent, and floating first mortgage rates were 20 per cent. Those were high rates even in real (inflation-adjusted) terms: the Reserve Bank’s survey of expectations then (1987) had medium-term inflation expectations at around 8 per cent.

Even almost a decade later, when low inflation had become an entrenched feature, 90 day bank bill rates (the main rate policy focused on then) peaked at around 10 per cent in mid 1996. And the newly-issued 20 year inflation indexed bonds peaked at 6.01 per cent (I recall an economist turned funds manager who regularly reminded me years afterwards of his prescience in buying at 6 per cent).

But 90 day bank bill rates are now a touch over 1 per cent, and a 21 year inflation-indexed bond was yielding 0.53 per cent (real) on Friday.

So, yes, interest rates were extraordinarily high for a fairly protracted period, and – once inflation was firmly under control – needed to fall a long way. But by any standards what we are seeing now is extraordinary, quite out of line with anything ever seen before, not just here but globally, not just in the last 50 or 100 years but in the last 4000.

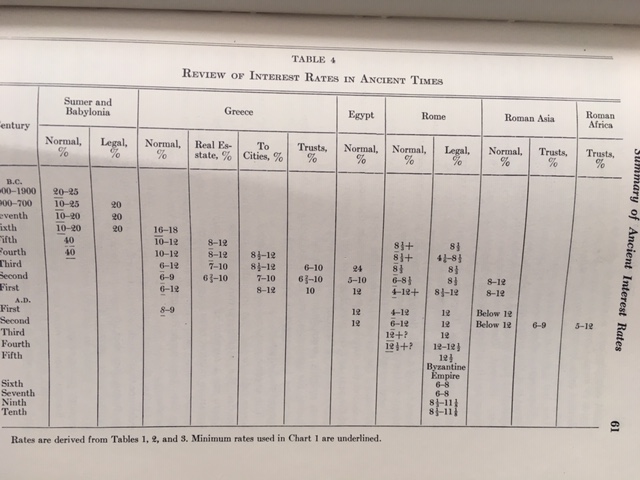

A History of Interest Rates: 2000BC to the Present, by Sidney Homer (a partner at Salomon Brothers), was first published in 1963, and has been updated on various occasions since then (I have the 1977 edition in front of me). It is the standard reference work for anyone wanting information on interest rates from times past. It is, of course, rather light on time series for the first 3700 years or so, and it is western-focused (Sumeria, Babylon, Egypt, Greece, Roman and on via the rest of Europe to the wider world). But it is a wonderful resource. And you probably get the picture of the ancient world with this table – the individual numbers might be hard to read, but (a) none of them involves 1 per cent interest rates, and (b) none of them involves negative interest rates,

(This brief summary covers much of the same ground.)

All these are nominal interest rates. But, mostly, the distinction between nominal and real rates was one that made no difference. There were, at times, periods of inflation in the ancient world due to systematic currency debasement, and price levels rose and fell as economic conditions and commodity prices fluctuated, but the idea of a trend rise in the price level as something to be taken into account in assessing the general level of interest rates generally wasn’t a thing, in a world that didn’t use fiat money systems. In England for example, where researchers have constructed a very long-term retail price index series, the general level of prices in 1500 was about the same as that in 1300. In the 16th century – lots of political disruption and New World silver – English prices increased at an average of about 1 per cent per annum (“the great inflation” some may recall from studying Tudor history).

But what about the last few hundred years when economies and institutions begin to become more recognisably similar to our own? I included this chart in a post the other day (as you’ll see, the people who put it together also drew on Homer)

How about some specific rates?

Here is the Bank of England’s “policy” rate – key short-term rate is a better description for most of the period (more than 300 years).

And here is several hundred years of yields on UK government consols (perpetual bonds)

And here – from an old Goldman Sachs research paper I found wedged in my copy of Homer – US short-term rates

Harder to read, but just to make the point, a long-term chart of French yields

The lowest horizontal gridline is 3 per cent.

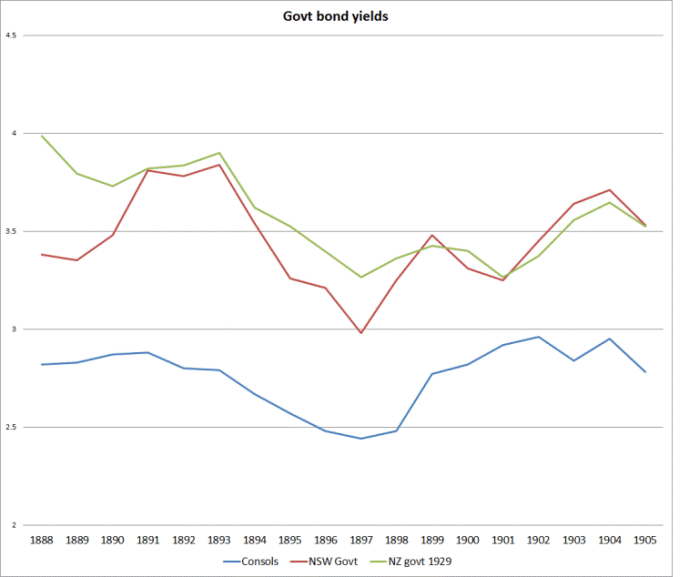

And, in case you were wondering about New Zealand, here is a chart from one of my earliest posts, comparing consol yields (see above) with those on NSW and New Zealand government debt for 20 years or so around the turn of the 20th century (through much of this period, the Australian economy was deeply depressed, following a severe financial crisis)

UK nominal yields briefly dipped below 2.5 per cent (and systematic inflation was so much not a thing that UK prices were a touch lower in 1914 than they had been in 1800). In an ex ante sense, nominal yields were real yields.

And in case you were wondering what non-government borrowers were paying, the New Zealand data on average interest rates on new mortgages starts in 1913: borrowers on average were paying 5.75 per cent (again, in a climate of no systematically-expected inflation). That may not seem so much higher than the 5.19 per cent the ANZ is offering today but (a) New Zealand rates are still quite high by global standards (UK tracker mortgages are under 3 per cent, and (b) the Reserve Bank keeps assuring us that inflation expectations here are around 2 per cent, not the zero that would have prevailed 100 years ago.

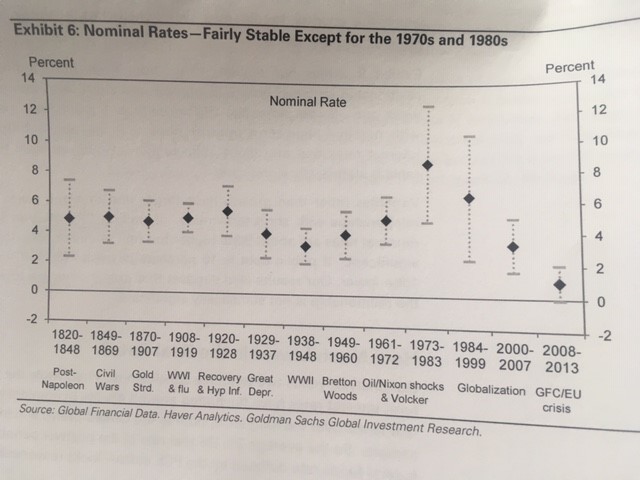

As a final chart for now, here is another one from the old Goldman Sachs research note

In this chart, the authors aggregated data on 20 countries. Through all the ups and downs of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century – when expected inflation mostly wasn’t a thing – nominal interest rates across this wide range of countries averaged well above what we experience in almost every advanced country now.

Systematic inflation started to become more a feature after World War Two, but even then it took quite a while for people to become accustomed to the new reality. And in the United States, for example, as late as 1965 the price level wasn’t even quite double that of 1925 – the sharp falls in the price level in the early 1930s were still then a fresher memory than (say) the high inflation of late 1970s/early 1980s New Zealand is now. Here, Homer reports average New Zealand long-term bond yields of 3.74 per cent for the 1930s, 3.18 per cent for the 1940s, and 4.13 per cent for the 1950s (1.1 per cent this morning).

Partly as a result of financial repression (regulation etc) and partly because of a new, hard to comprehend, era, we went through periods when real interest rates were zero or negative in the period of high inflation – but, of course, nominal interest rates were always then quite high.

I’d thought all this was pretty well understood: not so much the causes, but the facts that nominal interest rates and expected real interest rates across the advanced world (now including New Zealand, even though our forward are still among the highest in the advanced world) are now extraordinarily low by any historical standard – going back not just hundreds, but thousands of years. Term mortgages rates in Switzerland, for example, are now under 1 per cent – and rates which have been low for years are, if anything, moving lower. And all of this when most advanced economies now have something reasonably close to full employment (NAIRU concept) and have exhausted most of their spare capacity.

It is an extraordinary development, and one for which central banks deserve very little of the credit or blame: real interest rates are real phenomena, about the willing supply of savings and the willing demand for (real) investment at any given interest rate. Across an increasingly wide range of countries more new savings (household, business, government) is available at any ‘normal’ interest rate than the willingness to invest at that ‘normal’ interest rate, and so actual rate settle materially lower. I don’t have a satisfactory integrated story for what is going on. Sure, there are cyclical factors at play – which together with “trade wars” – get the day to day headlines. But the noise around those simply masks the deeper underlying puzzle, about something that is going on in so many economies (it isn’t just that we all get given “the world rate”). No doubt demography is part of the story, perhaps declining productivity opportunities, perhaps change in the nature of business capital (needing less real resources, and less physical investment, and there must be other bits to the story. I find it very difficult to believe that where we are now can be the permanent new state of affairs – 5000 years of history, reflecting human institutions and human nature (including compensation for delaying consumption) looks as though it should count for something. But can we rule out this state of affairs lasting for another 20 or 30 years? I can’t see why not (especially when no one has a fully convincing story of quite what is going on).

Thus central banks have to operate on the basis of the world as they find it, not as they might (a) like it to be, or (b) think it must be in the longer-run. There is the old line in markets that the market can stay wrong longer than you can remain solvent, and a variant has to apply to central banks. For much of the last decade, central banks kept organising their thinking and actions around those old ‘normal’ interest rates and that, in part, contributed to the sluggish recovery in many places and the weak inflation we now experience (relative to official targets). They need now to recognise that where we are now isn’t just some sort of return to normal from the pre-inflation era, but that we are in uncharted territory.

My impression is that most central banks are still no more than halfway there. Most seem to recognise that something extraordinary is going on, even if there is a distinct lack of energy evident in (a) getting to the bottom of the story, and (b) shaping responses to prepare for the next serious economic downturn.

Late last week I had thought that the Reserve Bank of New Zealand had got the picture. Whatever one made of the specific 50 basis point cut – my view remains that 1 per cent was the right place to get to, but that doing it in one leap, without any obvious circumstances demanding urgency or any preparation of the ground, only created a lot of unnecessary angst – I was struck by the way the Governor talked repeatedly at the press conference of having to adjust to living in a very low interest rate world. As I noted in a post on Thursday, that was very welcome.

And so, when I saw what comes next, I could hardly believe it. I’d still like to discover that the Governor was misreported, because his reported comments seem so extraordinarily wrong and unexpectedly complacent. Over the weekend, I came across an account of the Governor’s appearance on Thursday before Parliament’s Finance and Expenditure Committee to talk about the Monetary Policy Statement and the interest rate decision. I can’t quote the record directly, but the account was from a source that I normally count on as highly reliable (many others rely on these accounts). The Governor was reported as suggesting although neutral interest rates had dropped to a very low level, that MPs should be not too concerned as we are now simply back to the levels seen prior to the decades of high inflation in the 1970s and 1980s.

I almost fell off my chair when I read that, and I still struggle to believe that the Governor really said what he is reported to have said. I’m not the Governor’s biggest fan – and he has never displayed any great interest in history – but surely, surely, he knows better than that? He, and/or his advisers, must know better than that, must know about the sorts of numbers and charts that (for example) I’ve shown earlier in this post.

I get the desire not to scare the horses in the short-term (though it might have been wise to have thought of that before surprising everyone with a 50 basis point cut not supported by his own forecasts), and I agree with him that an OCR of 1 per cent does not mean that conventional monetary policy is yet disabled: there is a way to go yet. But what we are seeing, globally and increasingly in New Zealand, is nothing at all like – in interest rate terms – what the world (or New Zealand) experienced prior to the 20th century’s great inflation. Real interest rates are astonishing low – and are expected to remain so in an increasing number of countries for an astonishing long period – and interest rates and credit play a more pervasive role in our societies and economies than was common in centuries past. We all should be very uneasy about quite what is going on, and in questions around how/whether it eventually ends.

And central banks – including our own – should be preparing for the next serious recession with rather more options than those they had to fall back on last time when nominal short-term interest rates then reached their limits. Those limits are almost entirely the creation of governments and central banks. They could, and should, be removed,and could be substantially alleviated quite quickly if central banks and governments had the will to confront the extraordinary position we are now in – late in a sluggish upswing that has run for almost a decade.

I would have thought that quantatative easing around the world and a trillion dollar deficit in the US have something to do with the low interest rates. Countries are all wanting to depreciate their currencies.

Finally a Reserve Bank governor telling us to go out and spend to save NZ shows how completely out of whack things really are!

LikeLiked by 1 person

There are more people who are savers than there are people who are borrowers. It is therefore rather silly a suggestion to ask NZ to go out and spend when more people who are savers have less to spend? Also in dollar terms the amount of NZ Household borrowings almost equal NZ Household savings which also suggest interest rates up or down has no real net difference to the amount of disposable incomes available to spend up. Isn’t it about time our overpaid economists start to learn basic mathematics?

LikeLike

Hi Getgreatstuff

We agree at last!

LikeLike

I agree with you that it is weird (and inappropriate) for the Governor to be giving us lectures about getting out and spending.

But on the more substantive issue, huge fiscal deficits tend to drive interest rates up not down (they represent a reduction in the net savings occurring in an economy). The evidence for QE making much sustained difference to interest rates is also pretty slight (including, for example, countries like NZ and Aus that have not done any).

LikeLike

It’s schizophrenic comments from Orr. He is dropping rates knowing full well the banks will create cheap credit to fund asset inflation, But then tells is to spend like drunkin sailors in port.

Maybe he thinks with lower interest payments it will create more consumer surplus to spend.

LikeLike

An interesting post, Michael.

However, a fundamental question must surely be: “Why should we continue to allow commercial banks to create 98% of our nation’s circulating money?” Banks make insanely exorbitant profits from doing so.

As a consequence of our allowing commercial banks to create 98% of our nation’s circulating money, we have an inept RBNZ attempting to control inflation very indirectly, using such a clumsy tool as the OCR.

The current banking and monetary system is systemically unstable, because when banks are granting loans faster than old loan principals are being repaid, the quantity of money in circulation increases, and when banks are granting loans more slowly than old loan principals are being repaid, the quantity of money in circulation decreases. Too great a rate of money creation by commercial banks leads to a boom, and too little a rate of money creation by commercial banks leads to a recession, or worse, a depression.

In contrast, the New Zealand equivalent to the UK’s Promissory Notes Act 1704 could be repealed, preventing banks’ promissory notes from being used as money. An independent Money Creation Committee within the Treasury could monitor the quantity of money in circulation and each month order the RBNZ to create new electronic money and gift it, free of interest, to the government for spending into permanent circulation. New money would be created at a rate to just match economic growth, ensuring zero inflation. By this means, we could be freed from booms, recessions and depressions, and have continuous, steady economic growth instead, with stable real estate prices.

With commercial banks no longer having the power to create new money, they would have to become financial intermediaries that take in money from depositors, aggregate it, and on-lend it to borrowers, making an honest living from the margins between the interest rates that they pay savers and the interest rates that they charge borrowers. This, of course, is the capitalist system as described by Adam Smith in his classic 1776 treatise ‘An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations’. I would call it ‘people’s capitalism’.

In a people’s capitalism banking and monetary system, commercial banks would have to compete with all other financial intermediaries for savers’ deposits. Interest rates for loans would be set by supply and demand, with the government having no say whatsoever.

There would be no OCR, and a much-diminished role for the RBNZ.

LikeLike

Peter, as an apparent supporter of the “Chicago Plan” or narrow banking single circuit sovereign money systems as alternative to our current bank money based fractional banking or dual circuit (sovereign money for ESAS interbank settlements) system, you might like my submission to the Review Team and RBNZ on depositor protection.[ https://treasury.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2019-02/rbnz-p2-4064255.pdf ]

I see a wholesale change to such a system e.g.(as per Benes and Khumhoff) as too risky (uncertain outcomes) and disruptive to the current system to be supported by those who understand the difference and lacking necessary public support (benefits not perceived or understood).

In my view a shift to transaction balances being sovereign money owned by depositors would be a step in the right direction, eliminating the need for depositor insurance and providing a proactive counter to the threats of private digital currencies and their regulatory challenges.

On the interest rate anomaly Michael identifies, declining money velocity over the last decade (and longer) matched by undershooting inflation targets, may suggest that Central Banks have actually not grown the money supply fast enough to match money demand. Structural distortions (for housing in particular) have incentivized the shift in use of money created from spending to saving through asset purchases, so that the growth in the money supply has not boosted spending sufficiently to cause inflation.

So under current policy, I would expect more reductions from the RBNZ (negative nominal rates included), even though IMHO changes to the structural policies driving money uses is more likely to help restore real interest rates.

LikeLike

It also stops economies developing using the free market to service communities. Banks deceide how much currency is created and where it is directed. The banks deceide what sort of economy we have not the market.

LikeLike

Agreed, Mr Marcus.

In allowing commercial banks to create our highly variable money supply, instead of having our very own RBNZ create our permanent money suppy, we have gifted commercial banks so much power that we have become their debt-slaves.

Far too may people are so indebted to banks that far too great a proportion of their after-tax incomes is now going to the banks by way of their mortgage principal repayments — money that immediately goes back into the nothing from whence it came — and far too small a proportion of their after-tax income goes into the consumer spending that drives our economy and keeps people in employment.

For some reason not understood by me, Michael insists that the fact that commercial banks create mortgage loans ex nihilo is not the primary driver of the massive house price inflation we have suffered since the mid 1980s, when globalist, neoliberalist politicians allowed banks to buy out the building societies and become virtually the sole source of house mortgages. Previous to that, building societies were the major sources of house mortgages, aggregating and lending out their depositors’ savings. Building societies were money lenders, not money creators, in contrast to commercial banks, which are money creators, not money lenders.

With high inflation, those with mortgages get an easier ride, at the expense of those without.

With low consumer price inflation and low interest rates, we at first get very high house price inflation, but then things in the real estate market quieten down, as uncertainty in a slowing economy grips potential buyers.

This is one of the reasons why I advocate for a ‘people’s capitalism’ banking and monetary system, as I described above.

LikeLike

Agreed that’s something that Michael frustrates me over.

I’m a big fan of prof richard werner and his explanation of banks creating money.

LikeLike

In Germany they have small community banks that service the community. The main banks only have a small share of mortgage lending unlike nz. We had countrywide and United in nz.

LikeLike

The current property market slowdown is mainly due to the foreign buyers ban and China’s own restrictions limiting the transfer of the Chinese Yuan by its citizens.

But there is still a booming tourism sector and although a bit of a slowdown in international students due mainly to the governments incompetence in shutting down immigration processing centres around the world, it is still $17 billion of foreign cash every 12 months finding its way into the pockets of small businesses. This cash inevitably will go back into the Mega Mitre 10 stores, Bunnings, the Warehouse, placemakers etc which translates to new kitchens, bathrooms, extra bedrooms, landscaping etc. That adds value and puts upwards price pressures to property.

LikeLike

As a non economist can I offer the suggestion that over the last 3000 years populations have increased rapidly in all the advanced economies having the same effect as high immigration. More infrastructure and investment. Over the last 50 years populations in advanced economies have become static or falling. No population expansion pressure. Couple that with a slowing in technology at the moment until autonomous vehicles are introduced and you get low investment demand and low interest rates.

LikeLike

Without that integrated story, difficult for anyone to operate on the basis of what they see and hear about interest rates. And that doesn’t help (investment) demand so I hope a best selling author appears quite soon (non-fiction or otherwise).

LikeLike

Great blog and discussion here! I am no expert but would humbly suggest that a look at Marx (gasp) and the ‘tendency for the rate of profit to fall’ may shine some light. $2t + injected into the world economy since 2008 – extremely low interest rates and negative rates (!) would suggest it has not been able to find sufficient productive industry to stick to that will produce a return on investment (or rate of profit (rop=profit/capital)). As a side note the hyper expansion of speculative financial bubbles (derivatives etc) is another manifestation of the same phenomenon.

LikeLike

Interesting angle. The interesting question though would be why the tendency for the rate of profit to fall would finally have taken hold now, rather than at an earlier stage since the Industrial Revolution. There still seem to be lots of innovation going on.

But, as I say in the post, no one has a fully convincing story.

LikeLike

I would have thought the rise of international tourism and an aging population would be the full story that has driven the growth of the services industries leading to low profitability and low productivity.

LikeLike

Why now is a good question and I don’t know the answer. Perhaps the more pertinent questions are what does it signify in the bigger picture and (for me at least) when does capitalism reach the event horizon where it cannot recover from? If we look at recent history it seems the band aids are coming off (recently, post war – long boom & QE – terrifyingly short boom). If you consider capitalism as a process of money circulation (again per Marx) then the system is full and more rain is not going to help – at all. So if we cant print our way out (cashing in future economic growth that already is not realising – see low/neg interest) what next? If indeed we have 4000 year low interest rates then a long hard look at capital yeah nah yeah?

LikeLike

sorry, meant to say …at capital is in order …

LikeLike