Longstanding readers will know that I was pretty critical of the previous government for the utter absence of any sign of a set of economic policies that might have begun to reverse the decades of relative economic decline. Worse, they and their acolytes too often seemed to make up stories about how well things were going when the data pretty clearly pointed in the opposite direction. I’m not sure I’d be quite as harsh as Kerry McDonald and Don Brash, who recently gave the Key-English government an overall score of 0/10, but I’d be close, especially around productivity (and also around housing).

What has become increasingly disconcerting is that the new government – now almost a third of the way through its term – also has no credible ideas about reversing the decline and little interest either. They seem increasingly reduced to making stuff up as well, and trotting out the same lines again and again without any sign of a really understanding the challenge, without any sign of a compelling analytical framework, and without any reason to think that the policies they talk of will make any material (helpful) difference.

I woke this morning to the news that the Minister of Finance had an op-ed in the Herald explaining how the government was going to restore our economic fortunes. With suitably low expectations, I tracked it down. Even with low expectations, I was struck by how weak it was, and left wondering why the Minister and his PR team thought the article was a good idea.

The Minister begins thus

The coalition Government is helping business modernise our economy to be fit for purpose for the 21st century.

Presumably he is aware that one sixth of the 21st century has already gone? And that his party was in government for half that time? But let that pass: as rhetoric it might be empty, but it is probably harmless.

This means being smarter in how we work, lifting the value of what we produce and export, supporting the environment, planning for future generations and giving everyone a fair shot at success. It means making sure that all hard-working Kiwis share in the rewards of economic growth.

All of which is hard to argue with, but isn’t exactly a) specific, or (b) new. I keep a copy of National’s 1975 election manifesto by my desk, and flicking through it – 43 years on now – I think I spotted all those points (actually, in light of Eugenie Sage’s announcement on Sunday, I also found a pledge to “discourage all forms of environmental pollution and encourage the recycling of materials. We will place a levy on difficult-to-dispose-of products’). Labour’s 1972 manifesto, or its 1984 one, or its 1999 one probably had them all too.

Most New Zealanders know we cannot go on relying on a volatile mix of population growth, an overheated housing market buoyed by speculation, and exporting raw commodities as our growth drivers.

Quite a bit of that was in the 1975 manifesto too. They are old lines, each trotted out by politicians of either main party for decades as the symptoms presented. Not always even very accurately – does anyone actually think an “overheated housing market buoyed by speculation” added to national prosperity? And not with much sense that the speaker had any sort of robust model of the New Zealand economy. Let alone serious policies in response: for example, if this paragraph is to be believed, the current government is apparently uneasy about rapid population growth, but continues to run the same immigration policy as both its predecessor governments for the last 20 years.

And despite all this, a few sentences later the Minister of Finance tries to assert that

the fundamentals fuelling the economy are strong

Quite which “fundamentals” he has in mind – presumably not those in the previous quote (above) – isn’t clear. In fact, all he offers in support of his view is

Last week, the Reserve Bank said growth will still average 3 per cent over the next three years. And Mainfreight managing director Don Braid said recently: “I think the business environment is good right now.”

A government agency whose forecasts seem to command increasing scepticism among other forecasters, and one prominent business person. Perhaps you are persuaded. I’m not.

But finally we get to some of the things the government is promising. First, what the Minister presents as a key component

Our plan to become more productive is built on getting our infrastructure sorted. This year, and for the next 10 years, we will invest more than $4 billion getting roads, rail and coastal shipping humming. We are sorting out Auckland’s congestion to save the $1b loss in productivity it causes each year.

Haven’t we heard these infrastructure stories (“we are taking steps to clear the backlog”) for 15 years now? But even if they are doing everything well in this area, look at the number in the final sentence. $1 billion – assuming the estimate is robust – is a great deal of money to you and me individually, but this is an economy with an annual GDP of $280 billion. On the Minister’s own numbers, fixing congestion would lift GDP by about 0.36 per cent. It would be very welcome, but it is tiny relative to the scale of the economic underperformance: with no productivity growth at all for the last three years, it might take 10 similar initiatives to just reverse the further slippage (relative to other countries) in the last few years. But this was the only hard number in the entire article.

So what else does the Minister have to offer in his economic strategy?

We are investing to improve the skills of our workforce so that workers can adapt to changing workplaces. New programmes like our Mana in Mahi/Strength in Work apprenticeship scheme will get young people off the dole and support employers with the costs of giving them an apprenticeship to help them grow their business.

As I’ve noted numerous times previously, on OECD data New Zealand workers are among the most highly-skilled in the OECD. And where the government is spending most heavily in the broad area of skills, it seems to be in providing fee-free tertiary education – a policy that will (a) mostly redistribute money to people (and their families) who would already undertake tertiary education, and (b) to the limited extent it encourages further participation, presumably do so mostly among those for whom tertiary education offers lower expected returns. It doesn’t have the feel of a productivity-enhancing policy, and the government has not (that I’ve seen) offered any numbers to the contrary. As for getting “young people off the dole”, it is (of course) a worthy objective but haven’t we seen many such initiatives in the last 50 years?

Other policies supporting small and medium enterprises to manage costs include greater access to training programmes, e-invoicing and cutting compliance costs.

There may well be some useful stuff in that list. But surely every government in modern times has talked of cutting compliance costs? And, in practice, haven’t most ended up increasing them overall? The previous government liked to boast of the 500 (?) items that comprised its Business Growth Agenda, but none of it (not even all of it) began to reverse decades of underperformance. It was symptom of the drive for action without analysis.

New Zealand was built on innovation. The best path for us to get richer as a country is to invest in new opportunities and find better ways of doing things. The coalition Government is supporting business to lift research and development investment, with $1b set aside in the Budget for R&D tax incentives.

Hard to disagree with the second sentence, but without some compelling analysis suggesting that the government and its advisers understand why firms haven’t regarded it as worth their while to spend more heavily on R&D, it is difficult to be optimistic that more subsidies are the answer. As I noted in an earlier post on the government’s proposals in this area

R&D tax credits aren’t the only form of government spending to subsidise business R&D – in fact, the government’s new scheme involves doing away with the current grants. And as it happens, OECD numbers suggests we already spend more (per cent of GDP) on such subsidies than Germany (DEU), and quite a lot more than Switzerland (CHE). [both of which have far far higher levels of actual business R&D]

All of which might suggest taking a few steps back and thinking harder about why firms themselves don’t see it as worth undertaking very much R&D spending here. But given a choice between hard-headed sceptical analysis and being seen to “do something”, all too often it is the latter that seems to win out.

But we are only stepping up to the big stuff

Our bold goal for New Zealand to have a net zero emissions economy by 2050 is essential as we face up to climate change. This goal creates economic opportunities. The business community is alongside us, with 60 of our biggest firms forming the Climate Leaders Coalition. The $100 million Green Investment Fund and the One Billion Trees initiative are key parts of this work.

Perhaps it is “essential”. Perhaps it even creates “economic opportunities” – big changes in regulation and relative prices always do, for some people. But the government’s own consultative document, and modelling commissioned for them from NZIER, suggests that once one looks at the entire economy, a serious net-zero emissions target by 2050 will result in losses of real GDP per capita of 10 to 22 per cent (relative to the baseline in which no such target is adopted by New Zealand). No democratic government is history has ever consulted on proposals that would lead to such a dramatic fall in expected future living standards and productivity. And, as a reminder, on the government’s own numbers, the costs would fall wildly disproportionately on the poorest New Zealanders. And, yes, there probably will be a lot more trees planted – many of them probably on good, easy to access and harvest, land – but just last week the government had to announce large subsidies to get even that programme underway. Subsidies have never been the path to improved economywide economic prosperity. Of course, few suppose the government proposes adopting a net-zero target for economic purposes, but they should at least stop misrepresenting the analysis on the economic effects from their own consultants.

We are also committed to ensuring no one is left behind in our economy. That’s why we have put in place the Families Package and lifted the minimum wage. It is why we have a $1b annual fund for regional infrastructure and economic development opportunities.

So the regions are so “stuffed” that only an annual subsidy scheme is going to help ensure they aren’t “left behind”? That seems to be the implication of what the Minister of Finance is saying there. And perhaps the Minister skipped over the likely tension between the laudable desire (see above) to get young people off the dole, and the really substantial increase in the minimum wage his government is putting in place (at a time when there is little or no economywide productivity growth)?

There are challenges in the world that are outside of New Zealand’s control. That is why we are running a surplus and being prudent with our debt levels. We are also diversifying our export markets to create new opportunities for our exporters.

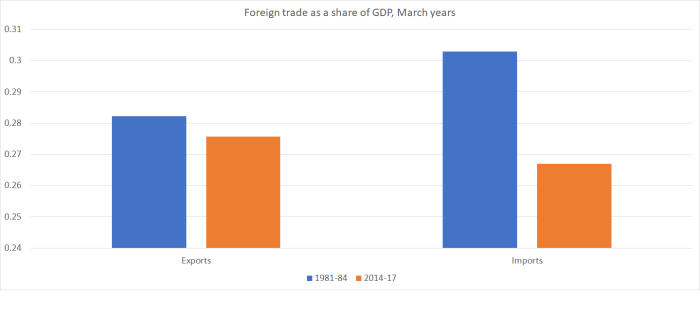

There is no hint of what, specifically, the Minister has in mind with his final sentence. But there is a certain sameness to it, going back decades and decades (nice quotes – including about the potential role of forestry – in that 1975 manifesto I mentioned earlier). And, actually, taken over the decades there has been a huge amount of diversification of export markets – no single country takes more than a quarter of New Zealand firms’ exports – but it hasn’t enabled New Zealand to lift the foreign trade share of its GDP much. In fact, over the last 35 years that share has shrunk.

As Don Brash noted in his article the other day, the previous government had fine words too

Key spoke about the need to increase the export orientation of the economy, and set a target for exports of goods and services of 40 per cent of GDP, up from 30 per cent when he came to office. Today, exports are just 27 per cent of GDP

Just no policies to make a difference.

The Minister of Finance attempts to end his article on an upbeat note

We are committed to working with business, workers and communities to build a stronger, more productive economy that delivers the quality of life that all New Zealanders deserve.

A worthy objective indeed, but there is nothing in what he told his readers that is likely to address – and begin to reverse – the decades and decades of underperformance. If we take seriously the government’s own numbers around the proposed emissions goal, the relative underperformance could be even worse under this government (were it to win nine years in office) than under its two predecessors.

I presume (hope) the Minister believes what he says, but until he starts to confront the implications of charts like this he is unlikely to make any progress (except perhaps by chance)

With a real exchange rate now averaging 25 per cent higher than in the previous 15 years, in a country where productivity has dropped further behind, it shouldn’t be any surprise at all that foreign trade shares are falling, that the economy is increasingly skewed towards the non-tradables sector (where competition is often, and often of necessity) quite limited, or that firms don’t see the likely payoff to investing heavily in R&D. These are classic symptoms of a severely unbalanced economy. Most often they arise from misguided government choices. In our case, the biggest single misguided choice is the grim determination – or perhaps enthusiastic dream – to keep on rapidly driving up our population in such an isolated location where the opportunities to take on the world from here seem few – and all the fewer with such a severely out-of-line real exchange rate.

Really successful economies – ones with materially stronger productivity growth than their peers – tend to have strong, and rising, real exchange rates. But that strength is a consequence of success, an outcome of success, a way of spreading the gains. Driving up the real exchange rate has never been a part of successful strategy to lift the relative productivity performance of the economy. The reformers here in the 1980s recognised the importance of a sustained lower real exchange rate as part of a successful economic transition. It is tragic that today’s political and economic leaders seem to have almost completely lost sight of that.

We have – and will have – a 21st century economy. But the question is whether it will be a struggling upper middle economy, with hazy memories of glory days long gone, or one that once again matches many of the richer countries in the advanced world, something I’m pretty sure we could do, but for a small number of people. If the government really believes they have the answer for how they can do it with a population that they actively drive further up every year, they surely owe it to us to lay out their reasoning, their analysis, with much more specificity than the Minister of Finance has yet done. That might include explaining why their clever wheezes and proposed reforms will make the difference their predecessors also claim to have aspired to for decades now.

Then again, perhaps tangible achievement no longer matters. Under the government’s wellbeing approach perhaps warm feelings will substitute for world-leading incomes?

Thank you Michael – an excellent, though worrying summary. The lemming like rush by all parties to the zero carbon economy is a massive issue. Why no-one in opposition has the gumption to ask the question(s) about the consequences of Shaw’s policy is beyond me. National’s support is cowardice – the counter case is there to be made.

The US has withdrawn from COP Paris (yet has lowered its emissions), Australia will withdraw and the BRIC’s are signed up but ignoring it.

Such a fundamental proposal for the country deserves thorough challenge and cost benefit analysis before being actioned. The opposition should adopt a strap line that asks – The Government’s Plan to adopt a zero emissions economy by 2050 will reduce real GDP by between $28 and $61 billion – there is no new green tech to recover from that and they have no plan to protect the country from that. This is de-industrialisation on an industrial scale

The Climate Leaders Coalition should similarly be called out every day. Their support for the Climate Change Commission is virtue signalling of the worst order. At core the reason they are all in is none wanted the other (their competitor) to get an advantage by not buying into some form of carbon cost.

Rather than big business the people to be convinced the zero carbon agenda is the right thing for New Zealand are the people who eke out a living here and most importantly those in the lower SES’s.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Kerry McDonald details why he believes New Zealand must hold a Royal Commission into the policy failures of successive governments since the Millennium

https://www.interest.co.nz/opinion/95318/kerry-mcdonald-details-why-he-believes-new-zealand-must-hold-royal-commission-policy

Thanks for that. I’ll run it by Paul Spoonley.

Another thing I intend to run by Paul Spoonley is Stephan Molyneux’s suggestion that we should separate culture and state? – Interesting?

LikeLiked by 1 person

If I were Finance Minister and my plan was to rebalance the economy by increasing savings and reducing the exchange rate, I would ask my staff to invent a whole other program of “busy work”, hopefully not too expensive, to give journalists something to write about and make it look like I was doing something. Voters are not interested in macroeconomic imbalances.

LikeLiked by 2 people

It is a lie that kiwis can’t save. Current savings deposits in the bank is currently $172 billion. Add Kiwisaver of $50 billion and NZ savings is a whopping $222 billion against household debt of $178 billion.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Open up the wishing well and throw in another coin and just hope to get a lower exchange rate

How, Michael?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Markedly cut the residence approvals targets (from the current 45000 pa to 10-15K). Doing so will markedly reduce (net) pressure on resources – since so much less investment will be required just to meet rising population needs – lower our real interest rates relative to the rest of the world, and lower the real exchange rate.

But even if that approach didn’t work – and after championing it for 8 years now, and not encountered any compelling arguments as to why it wouldn’t – the Treasury should have the issue front and centre, being encouraging research, debate etc about what is going on, and how the imbalances can be reversed.

(that was, of course, part of the motivation of the joint RB/Tsy forum where I first presented these ideas in public https://www.rbnz.govt.nz/research-and-publications/seminars-and-workshops/exchange-rate-policy-forum-issues-and-policy-implications

my paper https://www.rbnz.govt.nz/-/media/ReserveBank/Files/Publications/Seminars%20and%20workshops/Mar2013/5200823.pdf?la=en

LikeLiked by 1 person

Looking at the latest INZ residency stats: reduction from 52K in 2015/6 to 37K in 2017/8. That is substantial even if it does leave us as a world leader for legal immigration. But working visas are increasing. As we are today it makes little difference what visa a foreigner in NZ has: they consume our physical infrastructure and (I don’t know the word for it but lets call it) soft infrastructure – the investment in trained public servants such as teachers, nurses, police, doctors and even IRD staff.

We need to be concerned about long term work visas. Consider say a bus driver with a young family; if they have had children born in NZ or children attending school for many years or if a family member needs medical treatment then asking them to just leave NZ becomes problematic (OK downright wrong) or at least it does if they are obliged to return to a 3rd world country.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The NZD has been sliding downwards since Adrian Orr took a dovish attitude towards interest rates. See it was a simple change in the RBNZ narrative. Nothing at all to do with immigration which is still a record net gain of 63k.

LikeLike

I refer you to my post the other day: the moves are tiny in any sort of context

https://croakingcassandra.com/2018/08/17/exchange-rate-moves-trivial-in-historical-context/

On your other comment, in periods when we had very large net migration outflows the real exchange rate tended to be weak. Check the chart.

LikeLike

When the NZD is the 10th most traded currency in the workd and trading volumes is between $500 million and a billion every day and exports are only $60 billion a year. Clearly speculation trading based on trading confidence would be the reason. Your charting of the NZD to immigration would be merely pure coincidences of traders confidence.

LikeLiked by 1 person

actual and expected interest differentials matter, quite a lot

also, the period when we had the largest net outflows was one where the exchange rate was not even floating. These are real phenomenal, not just financial markets ones.

(and i’m not suggesting immigration is the only thing going on in exchange rate cycles – esp as much of the year to year variation in immigration is itself a response to changes in relative economic performance, and esp relative trans-Tasman labour markets.

LikeLike

A rise of 2% of the NZD results in a fall of 0.68 to 0.65 NZD/USD cross translates to $1.2 billion in happily increased profit margins on exports of $60 billion over a 12 month period and equally as distressing for an importer if they have no forward currency contracts. Not tiny when you look at the actual dollars a small movement would mean to industry.

LikeLike

If indeed there were such a finance minister, it might be one plausible comms approach

As it is, there doesn’t seem to be anything particular in the govt’s bag of policies that would sustainably lower the real exchange rate, or raise savings rates.

As I noted in a couple of posts last year, in his early years as MOF Bill English wasn’t afraid of talking macro imbalances (much good it did us!)

https://croakingcassandra.com/2017/06/06/rebalancing-not-so-much/

https://croakingcassandra.com/2017/06/02/exports-as-seen-from-the-2009-budget/

LikeLiked by 1 person

From a macro policy perspective I totally agree with your argument about the Big New Zealand pushing up asset prices, benefitting capital at the expense of labour and non-tradables at the expense of tradables. Slower migration would allow the RBNZ to ease monetary policy and the lower exchange rate would help the economy to rebalance.

Instead we are observing a chorus of analysts arguing that the government should throw fiscal caution to the wind and “modify” its debt targets. Personally I’m skeptical that all this will do is prolong the imbalances to the betterment of these vested interests. Whether the government can implement the infrastructure build-out efficiently is moot.

The second area that politicians simply refuse to look at is competition. It is clear that we’ve got an issue with corporate monopolies and oligopolies and rent-seeking whether it’s in banking, automotive fuels, supermarkets, airports/ports or other areas. The willingness of either this government or the last to take on the Big End of town seems about the same. Zero.

LikeLiked by 2 people

We used to run negative immigration as high as 40,000 net loss. The RBNZ in those periods have still been very hawkish and keeping interest rates higher than it needs to be. Can’t blame immigration when it is a philosophical problem with the RBNZ.

LikeLike

Perhaps the best we can do Michael is attempt to improve a policy here and policy there. Eventually (hopefully?) this sort of evolutionary process would lead to the economy getting better.

Recently I have worked on another option for improving housing and transport supply.

View at Medium.com

And I have looked at how improving battery technology might improve public transport in NZ.

View at Medium.com

These ideas will not suddenly turn NZ into a Germany or a Switzerland but they might help at the margin?

LikeLike

I think so Brendon. We’ve got to look to ourselves to move forward…

LikeLike

The Productivity Commission is doing some good work. The Minister could have indicated that the Government is working towards rolling out its recommendations.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I find them something of a mixed bag, but yes there is certainly some good stuff from there.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is pretty poor work by the Productivity Commission as they have not identified the root caused of our productivity poverty ie heavily subsidising Primary industries and tourism. If manufacturing got the same level of subsidies as primary industries and tourism we would have much higher productivity. Also they forgot to count the massive resources demanded by the 10 million cows in their productivity calculator.

LikeLike

Grant Robertson is not stupid. He knows there are two dialogues; one for the media to feed the voter and one with his advisors that would actually make changes. He probably has the same National party 1975 election manifesto by his desk and just translates it into modern language (diversity, gender, vibrant, Maori partnership, climate change) for his public lectures and press releases. What he and all his predecessors really needs is a simple to understand and implement policy with a clear logical basis.

I can’t manage anything as brisk as GGS’s ‘kill the cows’ but how about ‘close our universities!’.

All governments get taken over by pressure groups: the extreme being one man in charge with Louis 14th “L’état, c’est moi” which was also used by Stalin, Mao and maybe now by President Xi. The USA was taken over by its Military–industrial complex which may have harmed many worldwide but did produce the internet and GPS. Oligarchies are common and so are alliances of warlords (still found in Afghanistan and Somalia). However NZ like many other countries has been taken over by tertiary education. Decisions are not made for the good of the entire population but for the good of universities.

People are most energetic and innovative from the age of about 18 to 24 but in NZ the more capable half of our young people are not actually making anything – they are being stifled in universities. In my day it was 4% going to uni not 50% but even then it was clear that most students were wasting time; the knowledge being crammed would be soon forgotten and if by chance remembered never used again.

How would this galvanise NZ’s economy? The immediate effect would be a one off windfall profit by selling off Uni buildings and land with a secondary benefit from reducing congestion in our main cities. The savings on student allowances and accommodation benefits would be considerable and immediate. The average worker would be working for about 45 years not 41 which is an instant 9.8% increase in productivity. Another benefit would be the many creative ex-uni staff having the opportunity to disprove the adage ‘those who can do and those who can’t teach’.

What purpose do universities serve? Their main purpose is to be a source of graduates for employers who don’t want the skill but they do want the proof of diligence. That could be achieved by looking at school results but saving everyone 3 or 4 years and giving employers a more flexible and keen to learn employee. Incidentally schools in NZ would be greatly improved if they were not entirely focused on obtaining university entrance. The very rare person with a disinterested desire for academic learning can log into the Harvard and MIT websites.

Found on the internet “”Jim Flynn believes reading great literature could be better than a university education”” and of course he is right.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Given that the government now has a duty of care for all sorts of diseases entering the country having lost in court over Chinese Gooseberries(kiwifruit) viral outbreaks due to a dumb judge trying to be a boffin scientist and writing up 500 pages of legal scientific precedents, the government will now spend hundreds of millions in border control and disease control all over the country heavily subsidising Primary Industries.

$500 million has already been budgetted for culling cows which is only 50% of the costs. The cost of killing cows is being subsidised by the government. Given that the government now has a duty of care and was made 100% responsible for Chinese Gooseberry diseases this would likely see the government fully liable in the future for all such Primary Industry diseases which makes the culling subsidy now around $1 billion.

If manufacturing industries got the same level of subsidies as primary industries then we would have a high skilled labour force rather than the brain dead labour now needed in the Primary Industries.

LikeLike

Sympathetic as I am to the line that much tertiary education is more about signalling than human capital/knowledge acquisition, I’m not sure I would go very far down the “scrap the universities” line!

“Grant Robertson is not stupid”. Indeed. But the question is whether his talents are being used to simply keep things tidy (and stable) while pretending there is some more serious econ strategy – if so, it would put him in the same class as English/Joyce – or whether indeed there is something more serious and substantive in train. Thus far – and he had several years as Finance spokesman to prepare – the evidence for the latter interpretation is notable mostly by its absence.

LikeLike

You studied economics and you are an economist. Not many graduates are like you.

There is a major distortion in politics. Our government’s first policy was increase the already serious subsidies received by tertiary education. My point is not whether it was of debateable value but the unthinking priority it received over far more important issues.

Jacinda and Grant reply to complaints about NZ’s lack of productivity with ‘we need more skills’ which they then interpet as spending more on tertiary education. We were better served by our politicians when they progressed from publican to Prime Minister rather than student directly into politics.

PS. I enjoyed being a student; it was a chance for a nerd to meet girls, to be less conspicuous when doing dumb things and it gave me time to dedicate to listening to jazz and playing billiards. I thank the 95% of Scottish school leavers who didn’t go to university and helped pay the taxes that allowed me to obtain a degree in general science that has never been used since.

LikeLike

I have quite a lot of sympathy with Jim Flynn’s great books approach, altho I suspect more people would get most value from reading the great books in a structured environment (eg a US liberal arts college as an undergrad programme, and then a subsequent programme for specific professional skills – law, medicine or whatever.

I suspect free fees is as much about “middle class welfare” – capturing the parent vote, in the same way as Grant Robertson’s 2005 initiative of interest-free student loans – as about any real belief that it will materially and usefully raise skill levels.

LikeLike

Strangely I have to disagree with you about literature. I’ve meet many people who live for literature but none who survived studing English literature at university. Admittedly a small sample.

My anti-university assertion is really an ‘anti-university for all’ hypothesis; the question is where should we draw the line. Given the immense sums of tax payers money spent on tertiary education there ought to be a careful analysis of where the money is spent productively and where it is largely wasted. The analysis needs to be written by an unbiased high level non-graduate economist.

LikeLike

I mostly agree with your second para.

on the first, the great books programmes aren’t just Eng lit, but philosophy, politics, theology, history – the great works of Western civ. The approach I had in mind has mostly gone out of fashion (with the politicisation of all forms of humanities study) but there are exceptions, eg

https://www.sjc.edu/academic-programs/undergraduate

LikeLike

yay… Pol Pot had a strategy… so did Hilter… Stalin reportedly had a plan…. The issue is not which politician has a plan, but what the incentives are to business to lift labour productivity…. munting on about the usual talking points is not doing anything….

I am so depressed…

LikeLiked by 1 person

I would have thought the incentives for business to lift productivity were self-evident. I’d ask the flip side – how can the state help inefficient, unproductive businesses to fail, allowing more efficient, productive businesses to expand?

All the corporate guff I hear at work is about how the best gains are made when you make up for your weaknesses by building your strengths, not lifting your weaknesses into mediocrity. How many of government’s policies are about lifting weakness into mediocrity rather than making good into excellent?

LikeLiked by 2 people

The best service usually equates to more people and not less people. Our largest industries are in providing services ie Tourism and international students is a $15 billion service business. Our aged care services is a people business and with the baby boomers aging rapidly expect more people to care for an aging population.

LikeLike

Advanced countries do not get rich looking after their elderly or even taking tourist. International students would be welcome export industry if unsubsidised. It would also seem a more plausible part of a serious growth strategy if it hung off the back of one or more really top-tier research universities (Harvard, Oxford, even NUS or ANU).

LikeLike

That OECD graph strongly suggests that the under-performance of productivity growth may be closely correlated to 40 years of currency over-valuation being the norm. The only stretch of relative sanity looks like 1989 to 20012 – when Don Brash was helming interest/exchange rates.

Our problem seems to be over-popularity. Banks and fund managers from all over want a piece of the rock star economy.No matter the true state of productivity, the world buys into our constant political spin and sends more money. Like right now, the sole purpose of our symbolic ‘zero-by-50’ policy is to bask in a green glow of international applause which will attract ethical funds like a magnet.

Here’s a thought – and it could be a masterstroke. PM Ardern declares a re-think (after lying on the floor) and announces New Zealand will follow our close ally USA (and perhaps Australia) by withdrawing from the Paris Climate Agreement.This would trigger a paroxysm of disapproval that would surely send the TWI below the 80- benchmark in less than a week!.

LikeLiked by 1 person

thanks a great post and a wonderful sharing. I like your site very much.

LikeLike