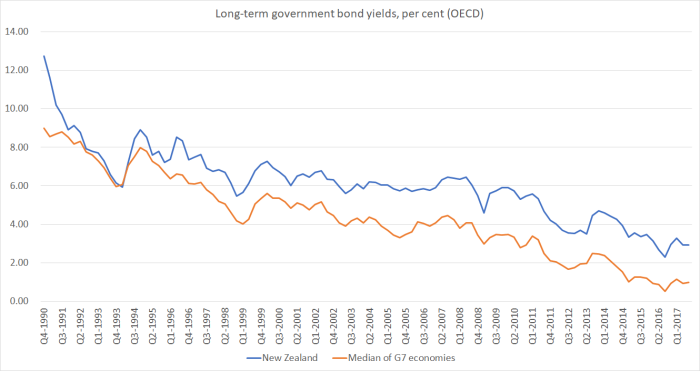

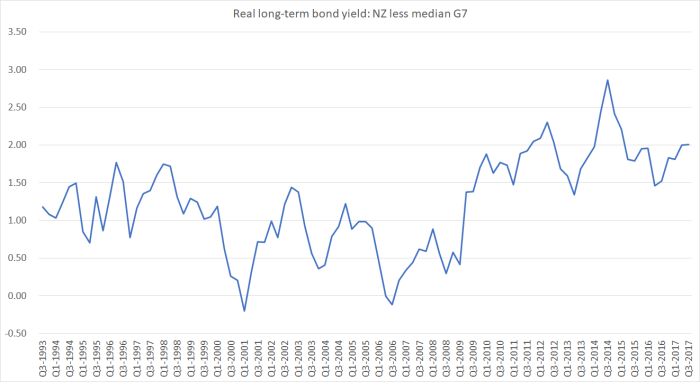

In Friday’s post, I illustrated how persistent and large the gap between New Zealand long-term interest rates and those in other advanced countries has been (and remains). The summary chart was this one

The gap is large and persistent whichever summary measure of other countries’ interest rates one looks at.

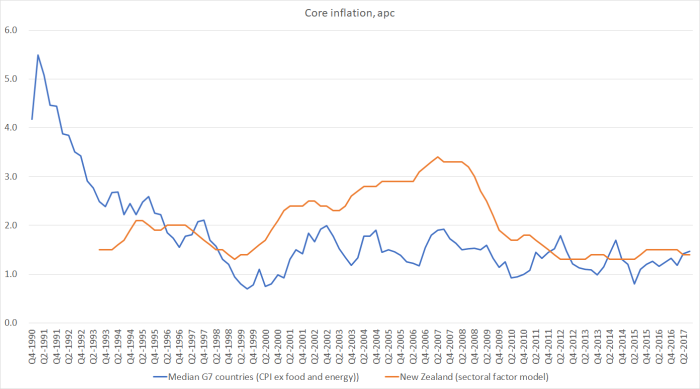

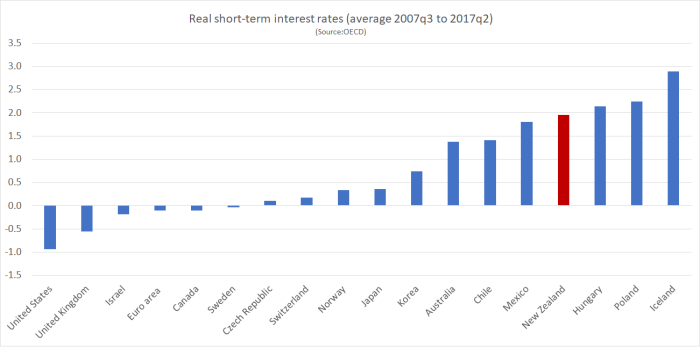

It is also there for short-term interest rates. In this chart, I’ve shown average real short-term interest rates for the OECD monetary areas (17 countries with their own monetary policies, plus the euro-area) for the last 10 years, adjusting average nominal interest rates for average core inflation (the OECD reported measure of CPI inflation ex food and energy).

Of the countries to the right of the chart, Iceland and Hungary have had full-blown IMF crisis programmes in the last decade, and Mexico and Poland had precautionary programmes. That isn’t meant to suggest that New Zealand is crisis-prone, just to highlight how anomalous our interest rates look relative to those of the other more-established advanced economies.

In yesterday’s post I reviewed some of the arguments sometimes advanced to explain why New Zealand interest rates have been persistently higher than those in other advanced countries. As I noted, these factors don’t look like a material, or compelling, part of the story:

- size (of the country),

- (lack of) economic diversification

- market liquidity,

- creditworthiness,

- accumulated external indebtedness,

- unusually rapid productivity growth

And, as I noted, none of those explanations has as a corollary a persistently strong real exchange rate. A story that can make sense of New Zealand’s persistently high real interest rates needs to be able to make sense of the persistently strong exchange rate, and also of New Zealand’s persistently poor productivity performance. As it is, in a country with a poor productivity performance and the disadvantages of remoteness, one might have expected to find persistently low interest rates and a persistently rather weak exchange rate.

At an economywide level, interest rates are about balancing the availability of resources with the calls on those resources. In principle, they have almost nothing to do with central banks – we had interest rates millennia before we had central banks. They also don’t have anything necesssarily to do with “money”, except to the extent that money represents claims on real resources.

In any economy with lots of exceptionally attractive and profitable opportunities, firms will be wanting to do a lot of investment. Resources used for investment today might well generate really strong returns in the future, but those resources can’t also be used for consumption (or producing consumption goods) today. Interest rates play the role prices typically do – acting as “rationing device”. Higher interest rates today make some people willing to consume a bit less now, and they also help ensure that the only the investment projects with the higher expected returns go ahead. In other words, interest rates help reconcile savings and investment plans. (If they couldn’t adjust that way, the price level would do the adjustment – and that is where central banks these days come in, adjusting the actual short-term interest rate to reconcile savings and investment plans while keeping inflation in check).

Sometimes the strong desire to undertake investment projects will be based on genuinely great new technologies. Sometimes it might be just based on a pipe-dream (credit-fuelled commercial property development booms are often like that). Sometimes, it will be based on direct government interventions (one could think of the Think Bg energy projects). And sometimes, it will simply be based on rapid population growth – people in advanced economies need lots of investment (houses, roads, shops, offices, schools etc).

Various factors can influence the desire to save. If firms in your country have developed genuinely great new technologies, it may seem reasonable to expect the future incomes will be a lot higher than those today. If so, it might be quite rational to spend heavily now in anticipation of those income gains (consumption-smoothing). Some governments tend towards the spendthrift, and others towards the cautious end of the spectrum. Tax and welfare rules might affect desire and willingness to save (although my reading of the evidence is that they affect more the vehicles through which people choose to save). Demographics matter, and compulsion may also play a part. Culture probably matters, although economists are often hesitant about relying on it as an explanation. Business saving is often forgotten in these discussions, but can be a significant part of total savings.

But if, for whatever reason, people, firms and governments don’t have a strong desire/willingness to save at “the world interest rate”, then (all else equal) interest rates in your country will tend to be a bit higher than those in other countries. And if firms, households and governments have a strong desire to invest (building capital assets) at “the world interest rate”, then (all else equal) interest rates in your country will also tend to be a bit higher than those in other countries. Quite how much higher might well depend on how interest-sensitive that investment spending is (in aggregate).

Of course, we don’t get to observe actual supply curves for savings, or demand curves for investment. We don’t know how much New Zealanders (or people in other countries) would choose to save or invest at “the world interest rate”. Instead, we have to reason from what we do see – actual investment (and its components) and actual savings.

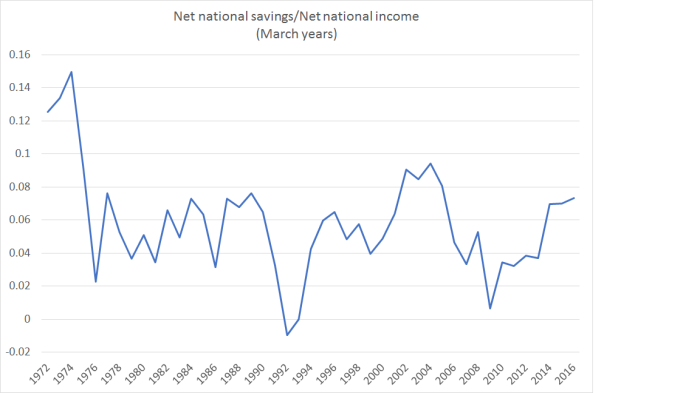

Take savings rate first (and by “savings” here I mean national accounts measure – in effect, the share of current income not consumed). Net national savings rates in New Zealand have been similar, over the decades, to the median for the other (culturally similar) Anglo countries, but lower typically than in advanced (OECD) countries more generally. Savings rates are somewhat cyclical, but as this chart illustrates, for some decades now they’ve cycled around a fairly stable mean (through big changes in eg tax policy, retirement income policy, fiscal policy, financial liberalisation etc).

All else equal, if tomorrow we woke up and found that somehow New Zealanders had a much stronger desire to save then our interest rates would fall relative to those in the rest of the world. But that is an illustrative thought-experiment only, not a basis for direct policy interventions. A relatively low but stable trend savings rate over a long period of time – especially against a backdrop of moderate government debt – suggests something more akin to a established feature of New Zealand that policy advisers need to take account of. A different New Zealand economy might well feature a higher national savings rate – more successful firms, wanting to invest more heavily over time to pursue great profit opportunities, retaining more profits to reinvest – but that would be an outcome of a transformed economic environment, not an input governments could or should directly engineer. Higher saving rates are not, automatically, in and of themselves, “a good thing”.

By the same token, if we all woke tomorrow and (collectively) wanted to build less physical capital (“invest less” in national accounts terminoloy), our interest rates would fall relative to those in the rest of the world. Actually, that is roughly what happens in a recession: pressure on scarce resources eases and so do interest rates (central banks typically helping the process along). But less (desired) investment is not, in and of itself, “a good thing”. Nor, for that matter, is more investment automatically desirable – in the last 40 years, investment/GDP was at its highest in the Think Big construction phase.

Whether over the last 40 years, or just over the last decade, investment/GDP in New Zealand has been very close to that of the typical advanced country. On IMF data, investment/GDP for 2007 to 2016 averaged 22.0 per cent in New Zealand, and the median advanced country had investment as a share of GDP of 22.1 per cent.

But these investment shares for New Zealand happened with (real) interest rates so much higher than those in the rest of the world. As I noted earlier, we can’t directly observe how much investment firms, households and governments would want to have undertaken at the “world” real interest rate – perhaps 150 basis points lower than we actually had.

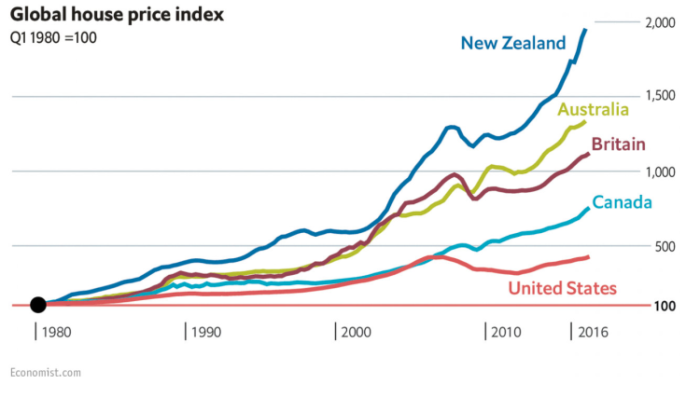

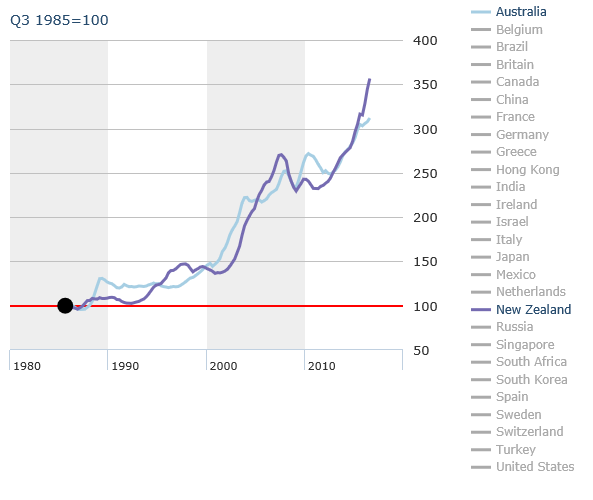

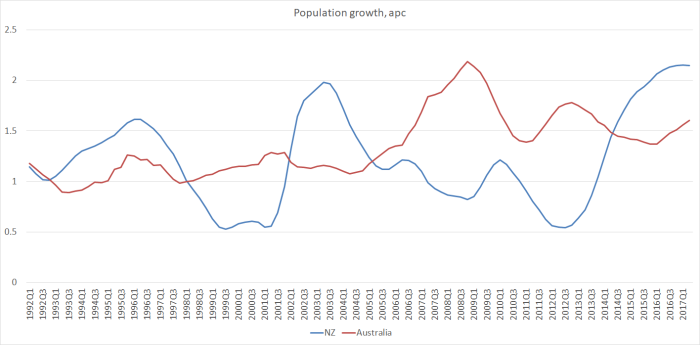

We might, however, reasonably assume that desired investment would have been quite a bit higher than actual investment. Both because some investment – whether by firms, households or (more weakly) government – is interest rate sensitive, and because we’ve had much more rapid population growth than the typical advanced economy. In the last 10 years, the median advanced country has had 6 per cent population growth, and we’ve had 13 per cent growth in population. More people need more houses, shops, offices, road, machines, factories, schools etc. All else equal, with that much faster population growth we’d have expected more investment here (as a share of current output) than in the typical advanced economy. But all else isn’t equal, because our interest rates are so much higher. That population-driven additional demand is one of the reasons why interest rates have been so much higher than those abroad. Combine it with a modest desired savings rate, and you have pretty much the whole story.

As I noted earlier, some investment is more readily deterred by higher interest rates than others (“more interest-elastic” in the jargon). Most of government capital expenditure isn’t – government capex disciplines are pretty weak, and if (say) there are more kids, there will, soon enough, be more schools. And more people will mean more roads. A lot of household investment isn’t very interest-sensitive either: everyone needs a roof over their head and (by and large) they get it. With a higher population growth rate than other countries, on average we devote a larger share of real resources to building houses than other advanced countries typically do (albeit less than might occur with well-functioning land markets). Business investment is another matter altogether. Businesses only invest if they expect to make a dollar (after cost of capital) from doing so. All else equal, increase the interest rate and less investment will occur. That won’t apply to all sectors, because in the domestically-oriented bits of the economy not only are interest rates higher, but the underlying demand is higher (more people). And so non-tradables sector investment probably isn’t very materially affected. But for the bits of the economy exposed to international competition (whether exporting, competing with imports, or supplying firms that do one of those) it is a quite different story. An increased population here doesn’t materially increased demand, and a higher cost of capital makes it harder to justify investment in the sector.

And all that is before even mentioning the exchange rate.

In an open economy, the floating exchange rate system is what allows countries to have different (risk-adjusted) nominal interest rates. Without a floating exchange rate, higher interest rates here would offer a “free lunch”, and the interest rate differences wouldn’t last. With a floating exchange rate, one can have differences in interest rates across countries, but the exchange rate adjusts such that, overall, expected returns are more or less equal across markets. Higher interest rates here are, roughly speaking, offset by an implicit expectation that one day our exchange rate will fall quite a lot. It appreciates upfront, to create room for that future depreciation.

The exchange rate, of course, also serves as a “rationing device”. Some of the high domestic demand spills over into imports. And the higher exchange rate makes exporting less profitable, all else equal. And so when we have domestic pressures (savings/investment imbalances at “world” interest rates) that put upward pressure on our interest rates, not only is business investment in general squeezed, but the squeeze falls particularly on potential investment in the tradables sector. Firms in (or servicing) that sector face a double-whammy: a higher cost of capital, from the higher real New Zealand interest rates, and lower expected revenues as a result of the higher exchange rate.

We don’t have good data on investment broken down between tradables and non-tradables sectors. But we do know that overall business investment as a share of GDP has been towards the lower quartile among OECD countries (whether one looks back one, two, three or four decades), even though we’ve had faster population growth than most. We also know that there has been no growth at all in tradables sector real per capita GDP since around 2000, and we know that the export share of GDP has been flat for decades (even though in successful economies it tends to be rising). Those stylised facts are strongly suggestive of a situation in which:

- lots of government investment takes place (market disciplines are weak),

- lots of houses get built (even if not enough – because people need a roof over their heads),

- a fair amount of investment occurs in the non-tradables sectors, despite the high interest rates, but

- a great deal of potential investment in the tradables (and tradables servicing) sectors has been squeezed out.

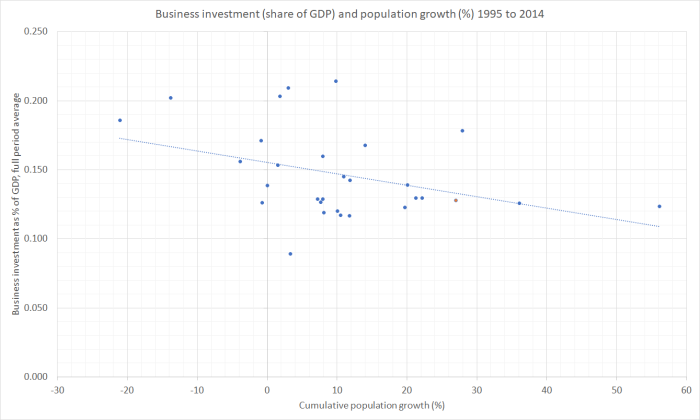

That is, roughly speaking, how we end up with rapid population growth and yet an investment share of GDP that is no different from that of a median advanced economy. We know that population growth seems to adversely affect total business investment across the OECD (I ran this chart a few months ago)

And it is surely only commonsense to reason that tradables sector investment will have borne a lot more of the brunt than the non-tradables sectors.

I’m not getting into the details of immigration policy in this post. Suffice to say that our immigration policy – the number of non-citizens we allow to settle here – is the single thing that has given New Zealand a population growth rate faster than that of the median OECD/advanced country in the last 25 years or so. It is, solely, a policy choice. Our birth rate is a little higher than that of the median advanced country, but we have a large trend/average outflow of New Zealanders. So, on average, the choices of individual New Zealanders would have resulted in a below-average population growth rate (again, on average over several decades). And that, in turn, would seem likely to have delivered us rather low real interest rates and a lower real exchange rate. Real resources would have been less needed simply to meet the physical needs of a rising population, and more firms in the tradables sectors would have been able to have overcome the disadvantages of distance. And our productivity outcomes – and material living standards – would, as a result, almost certainly have been better.

You can read about all this at greater length in a paper I did for a Reserve Bank and Treasury forum on the exchange rate and related issues back in 2013.