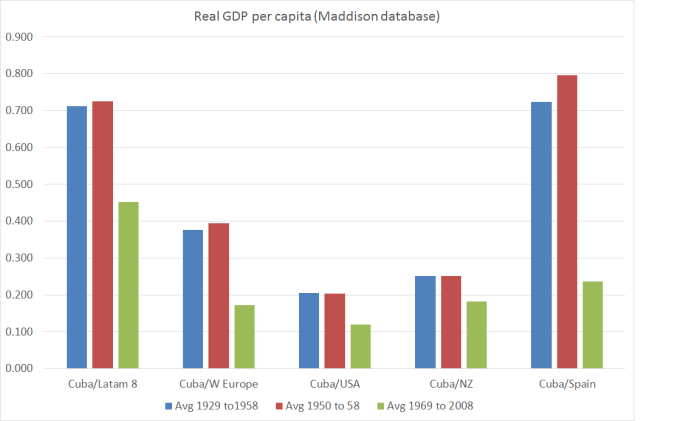

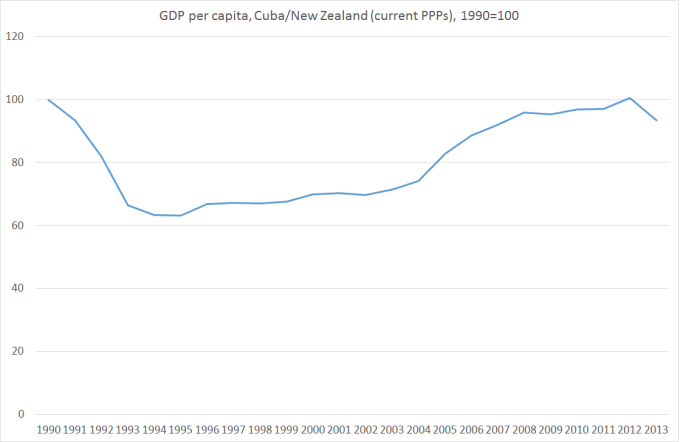

Some months ago I ran a post about some of various attempts to explain New Zealand’s decades-long relative economic decline, and to propose remedies that might reverse this performance. The first major piece along these lines that I’m aware of was by the Monetary and Economic Council in 1962. Since that was the year I was born, and economic outcomes now, relative to those in other countries, are worse now than they were then, despite all the various policy reforms and all the ink spilt in trying to make sense of the situation, I find that all rather depressing. A lifetime, and more, of relative economic decline.

In that earlier post I noted that the Productivity Commission, or more particularly its Director of Economics and Research, Paul Conway, had been at work for some time on a “narrative” of New Zealand’s economic underperformance, offering some combination of diagnosis and prescription. Earlier versions have been presented at various conferences and seminars here and abroad, and this week the finished product was released. (In the interests of full disclosure, I should note that the Commission paid me to provide some comments and suggestions on a relatively advanced draft of the paper, imposing no restrictions on me writing about the finished product.)

The paper, Achieving New Zealand’s Productivity Potential, is issued under Paul Conway’s name. There is no disclaimer, of the sort often seen on public sector agency research, that the paper represents only the views of the author and not necessarily those of the institution. I asked Paul about the status of the paper, and he suggested that my description, that it was his paper but that the Commission was “not unhappy with the content”, sounded about right.

The paper is well worth reading, and should be read by anyone with a serious interest in these sorts of issues. It should be reasonably accessible for most potential readers, and – at least by Productivity Commission standards – at 80 pages it is quite short. There are lots of interesting charts, and a variety of interesting issues/possibilities are dealt with (including some of the arguments I’ve been raising). It is a balanced and fair-minded report, and a really useful contribution to the debate that needs to be had. Even if the Prime Minister apparently no longer cares much about it – the recent statistics are just too bad for political comfort – productivity growth is the basis of any future long-term prosperity prospects.

The paper isn’t the last word on the issue by any means. That isn’t just meant as an observation that I disagree with some of it. As Conway notes, there are many issues where not enough research has been done, whether by academics, core policy agencies, or bodies such as the Commission. Some of the paper is inevitably a bit speculative. One goal of the paper might be to stimulate further debate, and prompt a demand for more serious research in a number of areas.

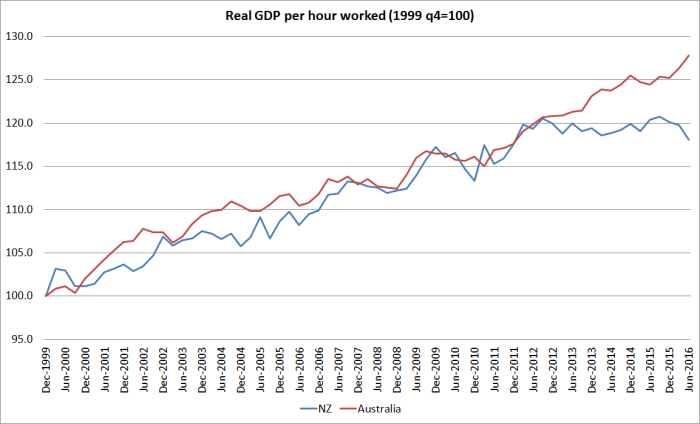

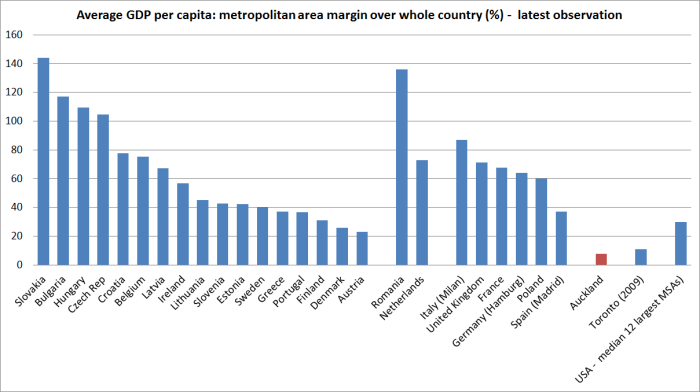

The Commission appears to be keen to be read by the government and its acolytes. That is perhaps understandable – only this week, the Prime Minister was dismissing out of hand theTreasury’s long-term fiscal projections, and much the same fate befell the 2025 Taskforce a few years ago. But on my reading, the desire to not immediately lose all readers from the current government has led them to over-egg the pudding in a few places, in writing up the story of the last few years. It isn’t central to the story, but the suggestion that New Zealand has materially closed the income gap to other advanced countries in recent years just isn’t supported by robust data, and praise for the Business Growth Agenda and regulatory reform both seem to go beyond the substance of what has been achieved. There is at least an arguable case that the quality of regulation has deterioriated further in recent years. Where it counts – productivity – at best New Zealand has not lost more ground relative to other OECD countries in the last decade or so. But the large gaps simply aren’t closing.

Even though he began his career at the Reserve Bank, these days Conway’s focus has tended to be on microeconomic issues, and often on firm-level research. New Zealand is particularly well-positioned for such research, because of the creation by Statistics New Zealand of the Longitudinal Business Database, which enables (a small tightly controlled group of) researchers to conduct studies using anonymised detailed data on individual businesses. Various researchers, at Treasury, Motu, the Commission etc, have produced a series of interesting papers looking at various aspects of firm behaviour in New Zealand. Some more results in that vein are included in Conway’s narrative paper. Indeed, this firm-level approach dominates the early part of the paper – he argues that “this approach puts firms at the centre of the analysis”.

Interesting as the results of these papers often are, I’m less convinced that the firm level analysis is very helpful for understanding long-term trends in overall economic (and productivity performance). Some of that may just be about short runs of available data. Thus, the paper begins with some international evidence about the differential labour productivity performance of leading and laggard firms over the last 15 years or so. There is a big difference. The Commission produces some evidence suggesting something similar for multi-factor productivity in New Zealand. But fascinating as that is, we have no way of knowing whether it is normal behaviour, or whether something unusual and new has been going on in the last 15 years. And, at least on this score, we don’t even know whether New Zealand has been doing more or less well than other advanced countries, even over this relatively short period. My concern has been that the availability of the data – itself a wonderful thing – is shaping the research agenda more than is really warranted. Perhaps that is inevitable – researchers will follow data, as water flows downhill – but even if so, we need to recognise that the questions that data can help answer aren’t necessarily the ones policymakers should be most concerned with.

None of this is to suggest that firms aren’t important. Most market economic activity takes place in firms. But firms, and managers and workers within them, respond to incentives, and should typically be presumed to do so in a rational way, that best serves their own interests. That includes choices to enter the market, to expand or cut back, or to leave it. Or simply never to set up at all. After the 50 or so years of our relative decline, it is likely that the structure of our economy, and the firms within it, look quite different than if a more successful path had been found. And firm-level analysis simply can’t look at the firms that never came into being – the exporting firms, for example, that might have developed if repeated aspirations to lift the export share of GDP (as in most other advanced countries) had been met. So, it isn’t entirely clear to me what we learn, that sheds light on overall productivity performance, from an analysis of the firms that happen to be here now. The firm level data, for example, suggest that the labour productivity performance of our leading firms is perhaps 30 per cent below that of advanced country peers. But that is, surely, just what we would expect. GDP per capita is – roughly – 30 per cent below that in many other advanced countries, and firms (and workers) will adjust so that, at the margin, resources earn their marginal product. Production structures will, typically, look different in poorer countries than in richer ones.

And so one of my criticisms of the Conway/NZPC paper is that while it is strong on highlighting symptoms, it is much weaker on analysing and understanding incentives (eg the reasons why firms, and governments, behave as they do). There is a tendency in the firm-level literature to treat firms as the cause of the problems – firms don’t invest enough in R&D, aren’t very good at management or what ever – without taking as a prior (perhaps to be tested) that individual firms and the people within them typically make decisions that appear rational, and indeed (on average) optimal for themselves. There is sometimes a sense that if only firms were as smart as the researchers studying them, the problems would be solved. The Conway paper largely avoids that tone, but it is still weak on the incentives/opportunities issue. If, as one study suggests, New Zealand firms’ management capabilities really are weak – on some measure – why has that happened? What makes it rational for firms to ‘under-invest” in such capability? Is it, perhaps, that what counts as high level capability in these surveys is, in fact, more of a luxury consumption product, that tends to accompany – rather than independently cause – economic success? I’ve previously posed similar questions about R&D. My own story – unproven – tends to be that firms would be likely to invest more in (genuine, not just classified for tax purposes) R&D, if the overall business environment (expected returns) were less unfavourable. Similarly, business investment in New Zealand (especially that in the tradables sector) probably isn’t low because businesses are badly run, or because business people are failing in some duty to their country, but because the expected risk-adjusted returns to much higher levels of investment just haven’t been there.

Another concern about the paper is that, for all the interesting paragraphs (and charts), I still came away from it uncertain quite how the author (or the Commission) would summarise the story. For example, as between the various firm-level “failures” and the big picture macro environment issues, there is no overall summary that gives me a good sense of which issues they think were really important, and which are rather less so, in explaining how we got to the poor outcomes we have today. The same is true of the way ahead: what initiatives have the potential to make a real and substantial difference and which, while perhaps nice to have, probably don’t matter that much. I suspect there is still a tension in the author’s own mind. His own micro-orientation comes through strongly in the final paragraph of the whole paper.

The broad policy considerations for lifting productivity offered in the paper highlight the importance of regulation that promotes knowledge diffusion into and throughout the economy and increased competition to improve resource allocation. Synergistic investment in skills, innovation and organisational know-how (including managerial capability) and other forms of KBC [knowledge-based capital] are also important. Flexibility, openness and receptiveness to new technology are also key and carry important implications across a range of policy areas.

This is a quite different tone than comes through at the start of the document (Foreword, Key Points, and Introduction). But more importantly, it has a strong whiff of “more of the same”, even though Conway reproduces the OECD’s chart that suggests that on a standard OECD set of micro-structural policies, New Zealand should already be much richer and more productive than it is. And it doesn’t really engage at all with the sense in the second half of the paper (which I think the author comes to perhaps rather late and a little grudgingly, or which he perhaps just struggles to fit with his firm-based focus) that macroeconomic conditions – whatever has caused persistently high real interest rates in particular – may, in fact, be a material part of the overall story of why the economy has systematically skewed away from growth in the tradables sector, and why it has managed such weak overall productivity growth for such a long time.

In fact, Conway comes a long way towards the view I have been espousing in recent years that the best explanation for persistently high real interest rates (relative to those abroad), which best fits other relevant stylised facts such as the persistently strong exchange rate, is a series of (insufficiently recognised/understood) demand shocks (see discussion on pages 39 and 40). He also recognises the likely connection between these persistently, and unexpectedly, high real interest rates and the way in which the real exchange rate has stayed high, even though productivity differentials have suggested that we should have seen a material depreciation in the real exchange rate. Nonetheless, when it comes to discussing the overall economic performance, and particularly the policy path forward, the real exchange rate tends to get only passing mention. By contrast, I think it is likely to be central to the story. It is a key part of the business environment that firms considering establishing or investing here have to take into account, and over which they have no control.

For my money, Conway also underemphasis the importance of New Zealand’s extreme geographic isolation. He notes OECD research that suggests distance represents perhaps a 10 per cent penalty on New Zealand’s GDP per capita, and recognises that – in some ways counterintuitively – distance may, if anything, be more of problem/constraint now, especially in knowledge-based industries, than it was in decades gone by. But I suspect he doesn’t take the issue sufficiently seriously. On my reading of the paper, most of it would be almost exactly the same if New Zealand was conveniently located in the Bay of Biscay, rather than in a remote corner of the South Pacific, distant from markets, suppliers, key networks etc. The continuing natural resource base of the overwhelming bulk of our exports doesn’t get a mention either, even though it might raise questions about whether New Zealand is a natural place to put ever more people – ever more people exposed to the “tax” of distance – if we hope to generate top tier first world living standards for New Zealanders.

Perhaps somewhat relatedly, there is a lot of discussion in various places of the potential challenges, including for individual firms, that being a small country – a quite different point from being a distant one – might involve. Small domestic markets, and the inevitable limits on the amount of competition in, eg, domestic services markets are real factors facing people considering investing here. And yet, it was puzzling that throughout the paper there were very few systematic comparisons across small advanced economies. After all, evidence tends to suggests that small countries have not, in fact, achieved less productivity growth than large ones. And it is a well-known stylised fact that small countries engage in much more international trade (exports and imports) than large ones do. Thus, while a firm in a small country might face the “need” to move into exporting earlier than a peer in Japan or the USA might, and face hurdles in doing so, actually the evidence suggests that they do it, and do so in ways that, taken together, generate high incomes and high levels productivity for their home nations. On my read, being a distant country is a problem – and one we can do nothing to change – but being a small country isn’t. Keeping on trying to become a slightly bigger, still very distant, country doesn’t look like a path to success. If, in fact, it is, the case isn’t made in the Conway/NZPC paper.

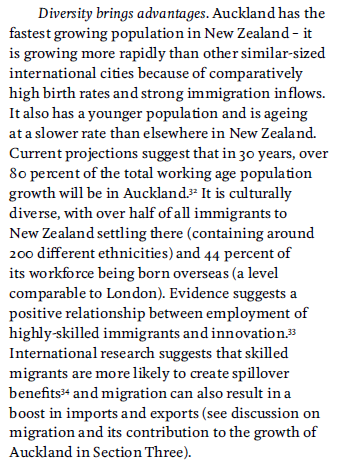

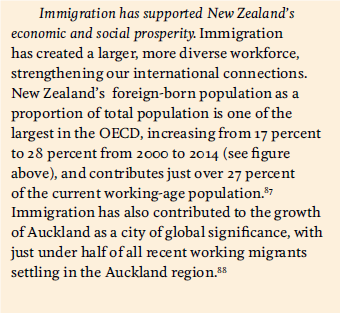

In fact, on that score, I was pleasantly surprised by where the author has got to on immigration policy. My impression is that his bias, and that of the Commission, would naturally tend towards favouring non-citizen immigration – it is, after all, fairly standard OECD orthodoxy. But, as I have consistently argued, the issue has never been a high-level issues of first principles – at some times and in some places, immigration may benefit all those involved, movers and natives – but one that requires a specific assessment in the New Zealand context.

But as Conway notes

It is difficult to conclusively assess the impacts of migration on the economy.

On the demand side

More broadly, and as discussed in Section 4, Reddell (2013) argues that demand-side pressures driven by strong migration inflows are part of the reason for high real interest and exchange rates in the economy, which supress investment and encourage resources into the low-productivity non-tradables part of the economy.

While

On the supply side, migration may generate small productivity increases via agglomeration.

Note the “may” and “small”

And

A supply of high-skilled migrants may also lift productivity in other ways, including improvements in the skill composition of the labour market, diversity effects and knowledge transfer.

And while they note that, relative to other OECD countries, our immigrants aren’t that lowly-skilled, the picture isn’t all rosy either

Recent evidence from the OECD’s Survey of Adult Skills shows that the skill level of the total overseas-born population in New Zealand is higher than for the overseas-born population of any other OECD country (Figure 5.8). This indicates that the migration system has done comparatively well at attracting high-skilled migrants. However, migrant skills are still lower than the skills of the New Zealand-born population, suggesting that migration inflows may be part of the reason for small decreases in the average quality of workers outlined in Section 3.

(Note that, as I have written about previously, the same OECD survey shows that our native workers are among the most highly-skilled in the OECD.)

Before concluding

Although up-to-date research on the impact of migration on employment and wages is lacking, it is possible that recent inflows of low-skilled migrants have restricted wage growth and the employment of low-skilled New Zealanders. In turn, this would encourage a reliance on cheap labour by some firms and industries. In conjunction with any macroeconomic effects on real interest and exchange rates, this may suppress investment and productivity improvements, and work against efforts to increase the employment of lower-skilled New Zealanders.

The Government’s objectives around migration for labour market purposes should be clearly focused on improving the skill composition of the workforce to improve international connection and the flow of new technology into the economy. New Zealand is currently a very attractive destination internationally and policy needs to use that advantage to target very highly skilled and well-connected migrants. Any reduction in the total number of migrants coming to New Zealand as a result of this sharper focus may help address New Zealand’s macro imbalances outlined in Section 4.

I couldn’t really disagree (but anyone who read only the Key Points or the Conclusion wouldn’t have sensed that there might be an issue in this area).

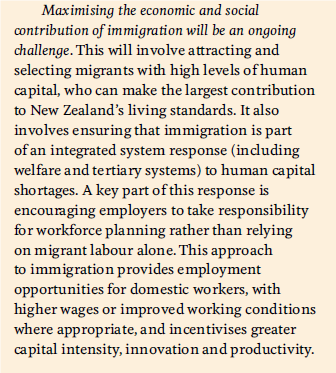

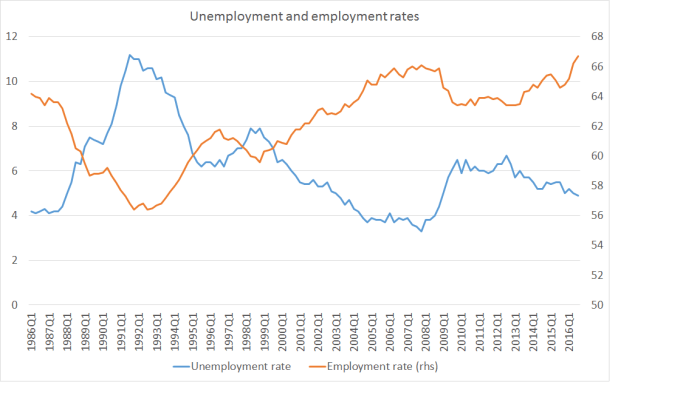

One last substantial issue also relates to labour. For a couple of decades now, at least since the labour market liberalisation in the early 1990s, there has been a story put around that perhaps our labour productivity growth (and MFP?) was lagging because we had put in place highly flexible labour markets which were able to absorb many people (typically lower productivity people) who would simply miss out on jobs in many other countries. If so, society as a whole might be better off, even if measured average productivity was a bit lower than it might otherwise be. There is quite a bit of that sort of flavour in the Conway/NZPC paper. Indeed, it even pops up in the call-to-action Conclusion of the entire paper.

The paper argues that New Zealand needs to shift from a development model based on increasing hours worked per capita to one in which productivity growth plays a more important role in driving growth in GDP and incomes per capita.

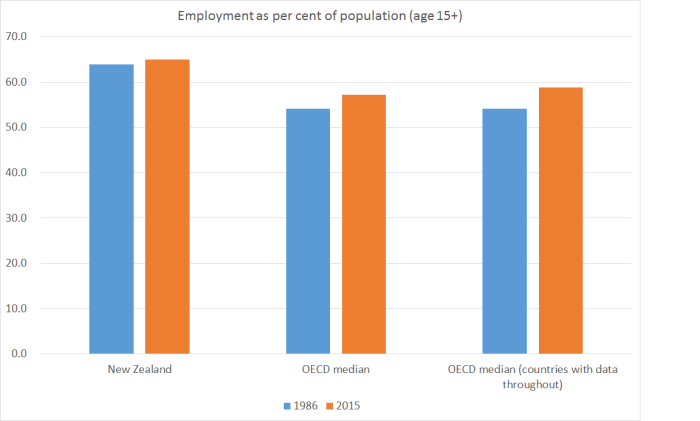

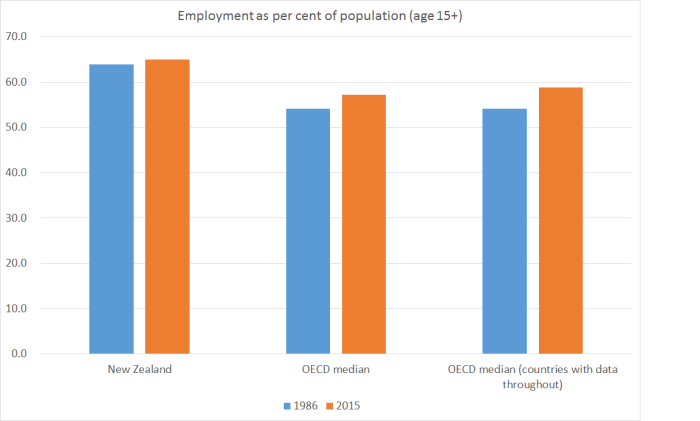

It is certainly true that average hours worked per capita are higher than in the median OECD country. And employment as a share of the adult population is higher here than in the median OECD country too. But that was true decades ago too. Our HLFS data only go back to 1986, but that isn’t such a bad starting point – it was before the bulk of the reforms of the late 80s and early 90s had taken effect, and before the very large, but temporary, disinflation and structural change increase in the unemployment rate occurred. In fact, New Zealand’s unemployment rate in 1986 (4.2 per cent) wasn’t much lower than the current unemployment rate.

But how do we compare against OECD countries?

Our employment rate has increased slightly over the 29 years to 2015, but the median employment rate in other OECD countries has increased a little more than that in New Zealand. Increased labour participation/employment rates cannot be part of the explanation for why over that same period we have continued to lose ground against other advanced countries, whether one looks at GDP per hour worked or at total factor productivity. And while it is hypothetically possible that the high level of the employment rate might be depressing the level of productivity, it is worth remembering that the three OECD countries with higher employment rates than New Zealand (Iceland, Sweden, Switzerland) also have higher GDP per capita and GDP per hour worked than New Zealand does.

There are plenty of other aspects of the paper I could write about, and I could touch on some of those here in more depth. One or two I might come back to next week. But to close, I would note that I was struck by this line from the final paragraph

With low productivity so entrenched in New Zealand, lifting this presents a monumental challenge for policymakers, business owners and workers.

Unlike most of the rest of the paper, it presents business owners and workers as part of the problem. But I don’t think the paper offers any evidence to that effect. Instead, we should generally assume that business owners and workers respond rationally to incentives, and to the climate they face. Governments shape so much of that climate. On my telling, governments have (perhaps unintentionally) consistently skewed the economy away from paths that could have allowed much better productivity and GDP per capita outcomes.

The issues are important and the paper is a valuable contribution. I encourage people to read it, and hope it stimulates some more debate on how New Zealand might best, in the paper’s closing words, achieve its productivity potential.