A chart of short-term nominal interest rates over the last thirty years looks something like this.

It looks dramatic for two reasons. First, I’ve started the chart from almost the historic peak in New Zealand’s interest rates, and secondly because in the late 1980s inflation and inflation expextations were still quite high. It wasn’t until around the end of 1991 that inflation got inside the then target range of 0 to 2 per cent annual inflation.

Here are the same two series adjusted for inflation expectations – the Reserve Bank’s two year ahead measure, from a survey that began in the September quarter of 1987.

It is a less dramatic picture of course but – as in most other countries – the trend is pretty strong downwards. In previous posts I’ve shown that over the last 25 years or so there has been no sign of New Zealand interest rates converging on those in other advanced countries.

For some purposes, thirty years just doesn’t provide that much data. There might have been 10000 calendar days, but there have only been two or three big cycles in interest rates, and a few smaller ones.

What has troubled me for some time – perhaps the more so as the years since the last recession have accumulated- is what happens when the next recession comes. We know that most advanced countries ran out of conventional monetary policy capacity in responding to the 2008/09 downturn. That, almost certainly, slowed the recover in demand and activity in many of those countries (even recognising the underlying productivity growth slowdown that was already underway before that recession).

Back in 2009, this might not have looked like much of an issue for New Zealand. After all, in 2009 the OCR troughed at 2.5 per cent and the time pretty much everyone – market pricing included – expected a fairly quick and substantial rebound. Despite a couple of ill-fated policy attempts at a tightening cycle, it just never happened. And years on now, inflation is still materially below the target midpoint, and the nominal OCR is even lower than it was then.

Views differ about the current position of the economy, but they are probably bounded quite tightly around an output gap estimate of zero. I emphasise that the unemployment rate is still above the NAIRU, suggesting a modest (and unnecessary) negative output gap, and even the most optimistic forecasters/commentators don’t see much sign of a materially positive output gap. There aren’t huge amounts of spare resources lying idle, but equally there isn’t massive overheating either. For better or worse, we should probably be treating current interest rates as something like “normal” – not perhaps in some very long-term sense, but certainly in terms of the sorts of macro conditions we’ve experienced in recent years.

And if interest rates are in some sense around normal/natural at current levels, we can’t prudently assume or plan on the basis that they are highly likely to rise from here (any time in the next few years). They might, but it looks as though it would take some material new development for that to happen. But it must be almost equally likely that the next material move is a fall. This isn’t a debate about where the next 50 basis point move comes from – reasonable people could probably differ over that range about where the OCR should be right now. Instead, it is about the next multiple hundred basis point move will be. They aren’t that uncommon – we’ve had three in the last 30 years.

I think there is a tendency – partly a recency error, partly the dramatic headlines of the times – to think of the interest rate adjustments over 2008/09 as unusually large. But they weren’t, especially not in New Zealand. There were some very big individual OCR adjustments – twice in a row the OCR was cut by 150 basis points- but in total they didn’t add up to much more than usual for a New Zealand downturn. Retail interest rates fell by 400 to 500 basis points. Over the short sample we have, that looks to be about the typical amplitude of New Zealand interest rate cycles.

Dramatic as the events of 2008/09 were internationally, when one looks at the New Zealand real economic data, 2008/09 simply doesn’t stand as an extraordinary downturn (although the subsequent weak recovery stands out more). Here is a chart of annual average real GDP growth (using an average of the expenditure and production measures).

The recession wasn’t quite as deep as the 1991 episode (which came after several years of pretty sluggish growth and not much sign of a positive output gap), and the slowdown in the growth rate wasn’t much larger than the slowdown from around 1996 to 1998.

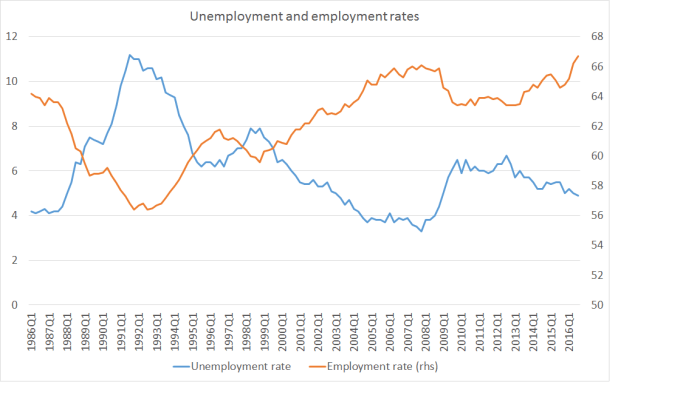

And here is a chart of the employment and unemployment rates.

Again, neither the change in the unemployment rate nor the change in the employment rate over 2008/09 particularly stand out.

It is a small sample of events, but on the basis of that limited sample, it looks as though we should be planning on the basis that in the next material downturn we’ll need to lower retail interest rates by 400 to 500 basis points. And, we should be planning for the possibility that such a downturn happens before economic conditions warrant raising interest rates much, if at all, from current levels.

But 90 day bank bill rates today are around 2 per cent, and term deposit rates are a bit above 3 per cent. The OCR itself is 1.75 per cent. There is a pretty clear consensus that, on current technologies and institutional practices, a rate like the OCR probably can’t be reduced below about -0.75 per cent – if it was attempted large holders of short-term assets would find it more economic to convert those holdings into physical cash. The Reserve Bank of New Zealand might have policy leeway of perhaps 2.5 percentage points, but they can’t safely assume they have leeway beyond that. And among the scenarios they have to plan on is that in the next downturn there could be a renewed widening of the spread between retail and wholesale interest rates – and it is retail rates that influence consumption and investment behaviour.

It is easy to say “oh, but we can just bring fiscal policy into play”. But, on the one hand, the Reserve Bank has no control over fiscal policy, and can’t just assume that the political imperatives driving/constraining fiscal policy will neatly fit with the Bank’s stabilisation (inflation targeting objectives). And, on the other, while New Zealand’s overall fiscal policy isn’t bad by international standards, it isn’t stellar either. The Crown balance sheet is in nowhere near as good shape as it was in 2008. It can take a lot of fiscal stimulus to compensate for the absence of monetary leeway – and of the numerous countries that deployed discretionary fiscal stimulus in 2008/09, I can’t think of any where it made a decisive difference (we can debate Australia). And, relative to the situation in 2008, we’ve since been starkly reminded over the last few years how (physically and financially) vulnerable to earthquakes New Zealand is, reinforcing the case for fiscal prudence (eg a positive net assets position as the norm).

In the next big downturn, there might be some scope for discretionary fiscal policy support (beyond the relatively weak – in New Zealand – automatic stabilisers) but no one – and certainly not the Reserve Bank – should be counting on it much.

The other reason to be uneasy is that the limited policy leeway is no secret. In typical downturns inflation and inflation expectations fall to some extent, but everyone recognises that the central bank will cut interest rates as much as necessary, to help support a recovery in demand, and keep inflation near target. Countries as diverse as the US and NZ could cut by 500 basis points in 2008/09 and did, and everyone knew in advance they had that potential.

But if the next material downturn were to occur in the next couple of years – and typical expansion phases in New Zealand haven’t last much longer than that – everyone will know that (abroad as well as here) central banks just don’t have that sort of leeway. The Fed might be able to cut by 1.5 percentage points, and the RBA and the RBNZ by as much as 2.5 percentage points. But that will be about it. Rational agents – firms, households, markets, will assume that inflation, and inflation expectations will fall further. That will make it even harder to stabilise activity and inflation.

(I’m not going to spend a lot of time on QE, but outside extreme crisis conditions, I think it is fairly common ground that it would take a great deal of QE to compensate for even 100 basis points of conventional monetary policy leeway.)

This isn’t a trivial, or abstruse technical, issue. At the heart of the case for discretionary monetary policy – the model advanced countries have run with since the 1930s – is the ability to adjust monetary conditions as much as it takes, to assist in stabilising the economy when it faces significant shocks. In the next downturn, there is increasingly unlikely to be enough leeway.

That should be concerning the Minister of Finance, the Secretary to the Treasury, and the Reserve Bank – not just in some idle handwringing sense, but commissioning work to respond to this threat. Perhaps there are secret projects underway in the bowels of the Reserve Bank and Treasury, but this isn’t work that should be kept secret; rather, it should be part of an open and ongoing conversation to help reassure the public and markets that the authorities have the capacity to respond decisively if and when the next serious downturn happens. There are solutions.

At the extreme, central bank physical currency could be withdrawn and completely replaced with electronic central bank liabilities, on which (say) negative interest rates could be paid. But that would take legislation and considerable organisation, and would be an unnecessary over-reaction, while there is still a considerable revealed demand to transact (in the mainstream economy) in cash. Better options might be to, say, cap the total issuance of Reserve Bank physical currency and allow an auction mechaism to set a variable exchange rate between physical and electronic Reserve Bank liabilities. Banks themselves could be allowed to issue currency again – on whatever terms they chose. Or the Reserve Bank could simply put in place an administered premium price on access to new physical currency (eg a 2 per cent lump sum fee would be likely to introduce considerable additional conventional monetary policy leeway). Each of these possibilities has potential pitfalls and possible legal issues. It would therefore be highly deisrable if an open consultative process was got underway, enabling a range of perspectives to be considered and debated in the cool light of day, rather than in the urgency of an unexpected recession. If, in the end, it all proved too hard – which I’d be reluctant to believe – the case for an increase in the inflation target would be strengthened. As the PTA needs to be renegotiated next year, now is the time to have this work underway. (And as the Reserve Bank has just given itself, somewhat unwisely, a three month holiday from reviewing the OCR – the next review is not til February – now would seem a particularly appropriate time to assign some joint Treasury and Reserve Bank resources to this work.)

What is particularly disconcerting is that there has been no hint that this is even considered an issue, whether in comments from the Minister, in speeches from the Secretary to the Treasury (including those commenting directly on monetary policy), in the Reserve Bank’s Statement of Intent, or in the increasingly rare speeches from the outgoing Governor. We should expect more.

(And in case anyone thinks otherwise, this issue is not an argument against the OCR cuts of the last year or so. Without them, inflation and inflation expectations would be likely to have fallen further, only increasingly the severity of the “lack of leeway” problem if a new recession were to strike a year or two down the track. The best way to maximise the limited remaining leeway is to keep interest rates low enough now that inflation is at, or even slightly above, the midpoint of the target range.)

On fiscal policy, is there a case that the US post-2008 boost also made a difference? Going by this, at any rate

https://www.brookings.edu/interactives/the-fiscal-barometer/

Incidentally the same folks have just come out with a survey rating the Fed’s communications, which may be of interest

https://www.brookings.edu/research/we-asked-fed-watchers-to-rate-the-feds-communications/

LikeLike

THanks for those links Donal

I’m not arguing that fiscal policy made no difference in 08/09 – with interest rates at whatever the practical lower bound is, it would be surprising if there were not a positive short-term impact on activity. I guess the question is more one of how large – and lasting – that impact is. Each of the US stimulus packages ran into pretty severe political constraints, and it took quite a few years to even get per capita output back to pre-recession levels (the sort of benchmark that is, to some extent at least, independent of arguments about structural slowdowns in productivity growth rates).

LikeLike

Or: “Ya caint eat gold or silver”… but perhaps we can cook up some recipes in the remnants of the can being kicked down the road?

LikeLike