There was an interesting post from Peter Nunns on Transportblog the other day, attempting a bit of a back-of-the-envelope decomposition of how various factors, including land use restrictions, might have contributed to the rise in real Auckland house prices over the 15 years since the end of 2001.

Nunns starts his decomposition with the suggestion that:

One simple way to disentangle these factors is to look at the relationship between consumer prices, rents, and house prices:

- When rents rise faster than general consumer prices, it indicates that housing supply is not keeping up with demand

- When house prices rise faster than rents, it indicates that financial factors – eg mortgage interest rates and tax preferences for owning residential properties – are driving up prices.

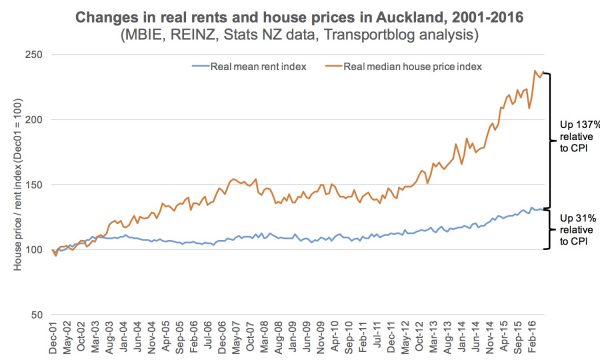

and with this chart

Disentangling the contribution of various factors isn’t easy. A lot depends on what else one can reasonably hold constant. Nunns seems to assume that holding real rents constant is a reasonable benchmark, and that we can then think about the change in net excess demand for accommodation by looking at deviations from that benchmark. Thus, roughly, he suggests that a 31 per cent increase in house prices can be accounted for by supply shortfalls.

Over this period, I’m not at all convinced that is right. Why?

Largely because of the big changes in long-term interest rates, which – all else equal – should have affected supply conditions in the rental market. Specifically, when interest rates fall a long way it is a lot cheaper than previously to provide rental accommodation (the available returns on alternative assets having fallen so much).

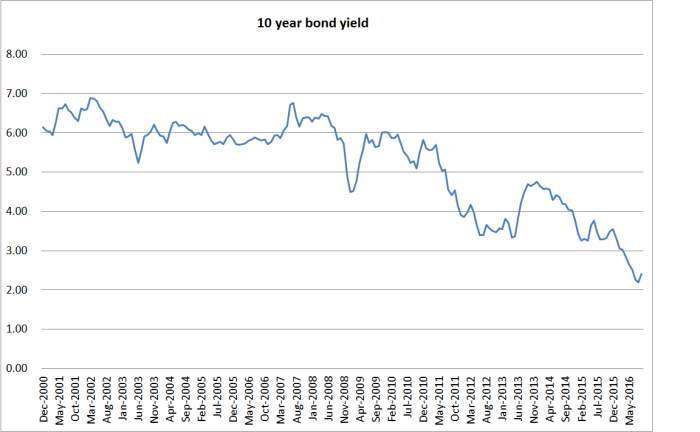

And what has happened to interest rates over this period? Well, here is a chart of the 10 year bond rate since the end of 2000.

There is always a bit of noise in the series, but long-term nominal government bond yields are now about 350-400 basis points lower than they were in 2001. A little bit of that is falling inflation expectations (around 50 basis points according to the Reserve Bank survey). But fortunately in 2001 we also had a 14 year government inflation-indexed bond outstanding, and we do so now as well. In late 2001, that indexed bond yielded about 4.6 per cent, and the current yield is around 1.6 per cent. Real long-term bond yields look to fallen by at least 300 basis points (and around two-thirds of that fall has taken place in just the last five years or so).

Short-term real interest rate haven’t fallen that much. Short-term rates are more volatile, so here I use a two year moving average.

| 1st mortgage rate | 6mth term deposit rate | |

| Dec 2001 | 7.99 | 5.86 |

| Sept 2016 | 6.14 | 3.59 |

Even on these measures, real interest rates have fallen by perhaps 1.5 percentage points.

In a well-functioning housing supply market, those sorts of falls in real interest rates might reasonably have been expected to be reflected in lower real rents.

Quite how much a fall one might have expected in such a market will depend on a variety of assumptions one makes. But if landlords had been looking for an 8 per cent annual real return on rental properties back in 2001, then even a 2 percentage point fall in real interest rates, might readily have been consistent with a 25 per cent fall in real rents – in a well-functioning housing market. If real risk-free rates have fallen by more like 300 basis points – as the indexed bond market suggests – that would be consistent with more like a 40 per cent fall in the rental cost of long-term assets.

These are all illustrative hypotheticals. They assume that new assets can readily be generated. But in a well-functioning housing markets, new houses can be readily generated. New unimproved land can’t be (there is a given stock, only what it is used for can be changed). But in well-functioning housing markets, the unimproved land component of a typical new house+land package will be quite low. Think of dairy land prices at perhaps $50000 a hectare and you start to get the drift. All else equal, in well-functioning housing supply markets, when interest rates fall unimproved land values should be expected to increase, but the value of land improvements and houses shouldn’t be much affected at all.

But even that story is a cautious one (biased to the upside). After all, interest rates typically fall for a reason – big trend falls don’t occur in isolation. One such factor is low expected future returns (eg lower expected rates of productivity growth). And interest rates are not a trivial factor in the cost of land improvements, associated infrastructure, and house building itself. Again, all else equal, lower interest rates should lower the real cost of bringing new houses onto the market – reinforcing the expected fall in real rentals.

Of course, this is so detached from the reality of Auckland (or New Zealand more generally) housing markets that it is difficult to even envisage such a scenario. We have land use restrictions – which tend to produce high land prices and high rents – and when those restrictions run head on into severe population pressures (especially unanticipated ones), it is hardly surprising that house and land and rental prices rise. But when that clash (between land use rules and rising population) occurs at time when real interest rates have been falling a lot, looking at trends in rents can badly confuse the issue.

I’m not wedded to a story in which all the increase in real house prices in recent years is down to supply restrictions interacting with rapid population growth. In his piece Nunns notes a couple of other possibilities

some other ‘financial’ explanations could include:

- New Zealand’s tax treatment of residential property, and in particular investment properties – unlike many of the countries we ‘trade’ capital with, we don’t have any form of capital gains tax on property. All else equal, this means that we should expect structural inflows of cash into our housing market, driving up prices

- The impact of ‘cashed-up’ buyers coming in without the need to borrow money to invest in properties – including, but not limited to, foreign buyers.

But….our tax treatment of investment properties has become less favourable not more favourable over the last few years (reduced and then abolished depreciation provisions, the introduction of the PIE regime, lower maximum marginal tax rates. If these arguments have force at all – and they typically don’t when supply is responsive – they should have worked in the direction of (modestly) lowering house prices over the last decade or so.

And while I suspect there is something to the “cashed-up foreign buyer” story, again any such demand only raises house prices when supply is unresponsive. If supply is responsive – which it would be without all the land use restrictions – such demand would be just another export industry.

Of course, the common story is that lower interest rates have raised house prices. And perhaps they have to some extent, but (a) recall that interest rates are lower for a reason, and real incomes now (ie the expected basis for servicing debt) are much lower than would probably have been expected a decade ago, and (b) lower real interest rates do not raise the equilibrium price of even a long-lived asset if that asset can be readily reproduced. In well-functioning housing markets, houses can be, and unimproved land is a small part of the total cost. If lower interest rates raise house prices, it is only to the extent that land use and building restrictions make it hard to bring new supply to market. (As it happens, of course, in much of New Zealand real house prices are no higher than they were a decade ago when interest rates were near their peaks.)

To a first approximation, trend rises in real house prices are almost entirely due to supply constraints. There can be all sorts of demand influences – some government-driven, some not – and it can be useful to identify them, but in well-functioning housing supply markets they don’t generate rising real house prices.

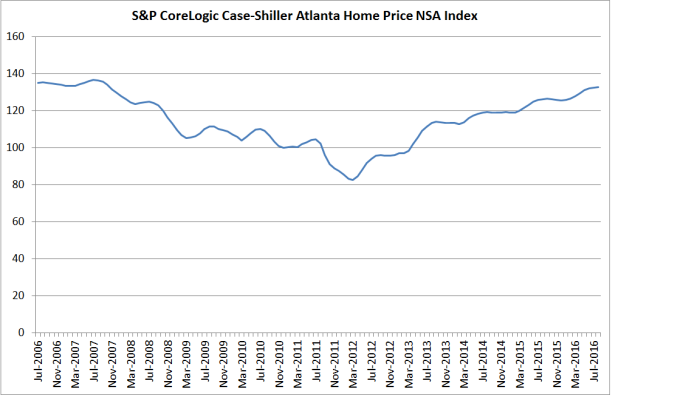

As just one illustration, here is a chart of nominal house prices for Atlanta over the last decade. Atlanta has had rapid population growth, has experienced significant falls in real interest rates (like the rest of the US), is in a country with mortgage interest deductibility for owner occupiers, and is not obviously a worse safe-haven for Chinese money fleeing the weak property rights of China, and yet nominal house prices are no higher than they were in 2006.