There was an annoying story on the front page of the Dominion-Post this morning. The online version of the story is headed “The big squeeze: Wellington’s population could almost double in the next 30 years”, a proposition which appears to be based on nothing more than compounding last year’s estimated population growth for the Wellington city area. I suppose anything could happen. The annual immigration target could be doubled or trebled, central government could go on a massive expansion path, or the private sector could discover hitherto untapped opportunities in Wellington.

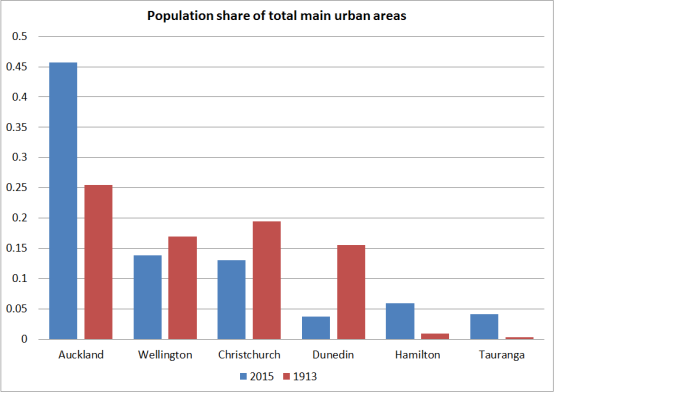

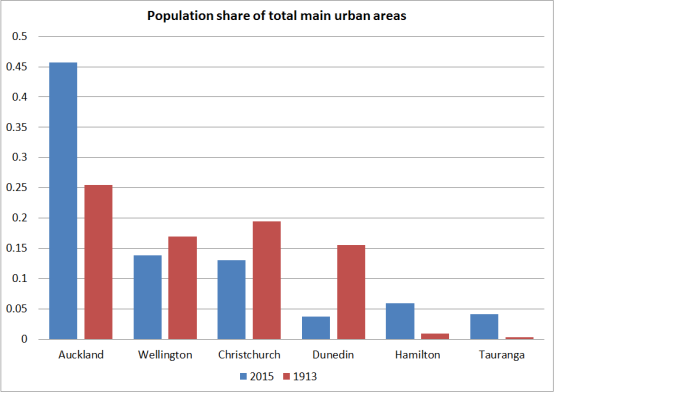

But if Wellington has outstripped Dunedin over the years, it has hardly managed strong growth. I went back to my 1913 New Zealand Official Yearbook. Back then, greater Wellington made up 17 per cent of the total population of the 14 large urban areas (a group made up of the places that were largest then, and those which are largest now – eg in 1913 Hamilton and Tauranga barely figured, while Gisborne and Timaru did). Today, the population of greater Wellington (including Kapiti) is about 14 per cent of the population of those 14 urban areas.

More recently, SNZ reports estimated data for urban area populations from 1996 to 2015. Over that period, even Wellington city’s population growth has only slightly exceeded population growth for the country as a whole – and been ever so slightly slower than population growth in Nelson. Take the greater Wellington area and population growth has been slower than that in greater Christchurch, despite the massive disruption from the earthquakes.

I’m not sure that this should greatly surprise anyone. Wellington has been helped by the growth of government (the regulatory state needs staff and it keeps growing, even if the tax share in GDP doesn’t) and by happening to have industries which it remains fashionable to subsidise (the film industry). On the other hand, it has a somewhat bracing climate – albeit one staunchly defended by some true Wellingtonians. There have been some good market-driven businesses built here, but not many choose (and find it optimal) to stay in the longer-term.

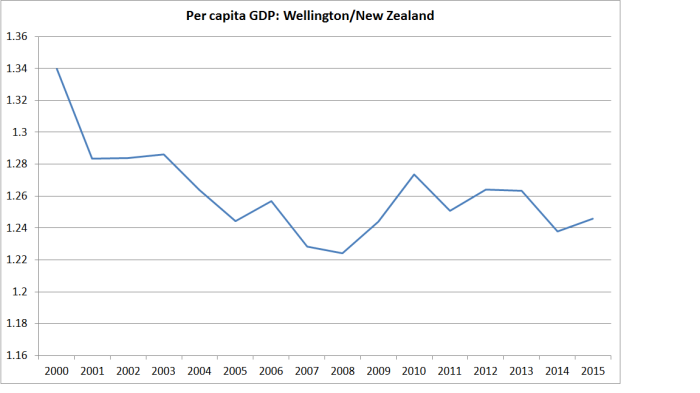

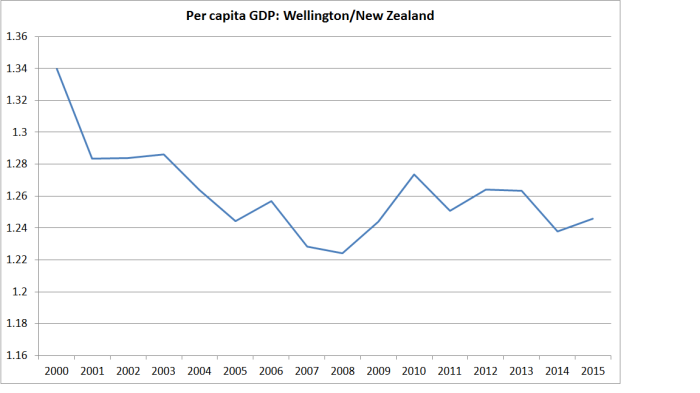

Average GDP per capita in Wellington is higher than that in New Zealand as a whole – no doubt reflecting some combination of the huge number of professional government and government-dependent roles, and the fact that Wellington tends to be attractive to young people not old ones (it is windy and not very warm). The labour force participation rate in Wellington averages higher than those in, say, Auckland and Christchurch. But over the 15 years for which we have regional GDP data, average per capita GDP in Wellington has been growing more slowly than that in the rest of the country (a similar story to Auckland).

So I don’t really see much chance that the population of Wellington – even just that of Wellington city – is going to double over 30 years. Even the Wellington City Council’s “chief city planner” (shouldn’t anyone from outside the old eastern-bloc be embarrassed to hold such a title?) acknowledges it is unlikely.

But the focus of the Stuff article was on the Wellington housing market. Of course, since it is an article about local authorities perhaps it isn’t too surprising that the word “market” does not appear at all – not once in a reasonably substantial article. The Council’s British chief bureaucrat, Kevin Lavery, is quoted instead as saying

Lavery said the 15 people who find themselves sitting around the Wellington City Council table after October’s election will have some big decisions to make on the supply, quality and diversity of housing in the capital.

Which really sums up all that is wrong with our system of local government. Councils and their officials simply should not be in the business of making decisions on the “supply, quality, or diversity” of housing in the city. That is what we have – or should have – markets for. They are the mechanisms through which private tastes and preferences are reflected and private businesses respond to that (actual and anticipated) demand. We need local authorities to do things like pave the streets, manage the water and sewerage, provide parks, and perhaps even run libraries. We don’t need them deciding what sort of houses people are living in and where The problems – including the affordability problems – mostly arise when officials and councillors get in the way. Now if Mr Lavery had simply been noting that no one can really predict what future population growth rates will be, or where people and businesses will prefer to operate, and that Council rules need to be sufficiently minimalistic and flexible to enable housing supply to easily respond to emerging demand, I’d have applauded him. But no, he doesn’t see a dominant role for the market, but for 15 elected individuals, with neither the expertise nor the incentives to get those decisions right – and that is no criticism of them individually, no one has that knowledge.

But the “chief city planner” is worried.

The danger was that developers would concentrate more on packing people in than on good design. “We’re not out to generate developments and profit margins for developers. We’re building communities.”

Council bureaucrats are “building communities”? The mindset is really quite starkly on display. In market economies, profit margins are part of what makes people willing to take risks, and build businesses – even develop new subdivisions or apartment blocks – taking the risk that things might actually go badly wrong. But “profit margins” seem anathema to the chief planner. And “good design” seems mostly to be a mantra to impose the tastes of some on everyone, and raise costs of housing. Again, why is it a matter for local government?

It isn’t just the bureaucrats. Here is our Mayor, presumably somewhat torn between her Green Party credentials (supposedly sceptical of population growth) and her local authority boosterism.

Wellington Mayor Celia Wade-Brown said she believed her council had done plenty during her six years in charge to set the city up for a population boom.

It had signed off on a number of special housing areas with the Government, and was actively consulting communities in several suburbs on potential medium-density housing rules.

Establishing an Urban Development Agency this year would also help increase the city’s housing stock and keep prices in check, she said. The agency will be able to buy and assemble land parcels, and partner with developers.

It is all about bureaucrats and politicians, not at all about empowering markets. Nothing about respecting property rights or promoting market solutions – just put your trust in the Mayor and Council staff. I’m wryly amused by her references to SHAs. There are a few not far from here. One – on the site of an old church – now has a few townhouses almost completed. A much larger one, not 200 metres from where I sit, remains as overgrown, dark, brooding, and undeveloped as ever. I’m keen to see it developed – though I know many locals aren’t – but there is simply no sign of any progress.

I guess the election is coming up and the incumbent isn’t well-positioned but when she can end with the observation that

“When our average house price is $560,000 and the Government considers $600,000 to be affordable in Auckland, then I think our city is looking pretty good.”

it is as if very small ambitions indeed have triumphed.

One only has to fly over Wellington to realise just how much land there is in both Wellington city, and the greater Wellington area. No doubt, the development costs are higher than those for flat cities such as Hamilton, Palmerston North or Hastings. But there is little excuse for average house prices of $560000 – responsibility for that mostly rests with the mayor, councillors and their legion of planners, aided and abetted by central governments that have allowed councils to have such powers.

The Productivity Commission’s draft report on a new urban land use policy framework is apparently due out next month. They had a mandate to be ambitious in their proposals. The Commission has so far shown a disconcerting enthusiasm for giving more powers to councils and governments, not fewer (they are bureaucrats themselves, so perhaps even if disappointing it shouldn’t be so surprising). I hope they take seriously the possibility of largely withdrawing the state (central and local) from the urban planning business. There was a nice piece the other day from a US commentator, Justin Fox, marking the 100th anniversary of zoning in New York.

It also appears to have been the first set of land-use rules in the U.S. that (1) covered an entire city and (2) used the word “zone.”

That was 100 years ago Monday. So happy birthday, zoning! OK if we kill you now — or at least maim you?

There’s a thought. Put markets, and private contracts, back in the driver’s seat, and let local authorities respond to private sector developments, efficiently delivering the limited range of services we really need councils to provide. Don’t “plan communities”, but provide services to ones that develop. (And that doesn’t include airport runways.)