In his weekly column in the Herald yesterday, Brian Fallow pointed out how unimpressive New Zealand’s recent economic growth performance has been. His article was headed “Froth disguises the facts” , and highlighted again how overall activity levels are mostly sustained by high levels of immigration, and that per capita GDP growth has been weak (and recent per capita income growth even worse).

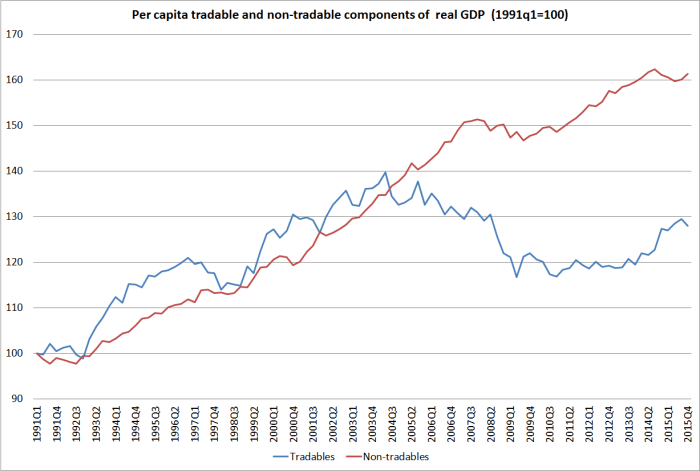

That column prompted me to dig out the latest data to update a chart I ran (with caveats) a few months ago, showing trends in per capita tradables and non-tradables components of GDP. Here, the tradables sector is the primary sector (agriculture, forestry, fishing and mining) and the manufacturing sector from the GDP production measure, and exports of services from the GDP expenditure measure. The non-tradables sector is the rest of GDP.

It is a pretty depressing chart. Per capita GDP in the tradables sector at the end of last year was still a touch lower than the level first reached in December 2000, 15 years previously. Across the terms of two governments, both of which constantly talked of “international connections”, aiming for big increases in export shares of GDP etc etc, there has been simply no growth at all in the per capita volume of the stuff we produce in competition with the rest of the world. As I’ve noted previously, the Christchurch repair process has inevitably skewed things a little, but it doesn’t do much to explain such a dire underperformance over 15 years.

Instead, with almost equal abandon the Clark-Cullen and Key-English governments have pulled ever more people into New Zealand, an economy that appears unable to compete sufficiently strongly internationally to see any growth at all in per capita tradables sector production. All economies have, and need, both tradables and non-tradables production, and there is nothing inherently bad about non-tradables production, but if we were to have any hope of catching up again with the rest of the advanced world’s productivity and per capita incomes it almost inevitably has to come from firms finding New Zealand an attractive place to produce stuff (goods, services, or whatever) that takes on and beats producers in the rest of the world. No matter how good our other regulatory settings are – and if they aren’t typically great they mostly aren’t that bad – that simply isn’t likely with the sort of real exchange rate we’ve had over the last decade, itself the result of the persistently high real interest rates (relative to the rest of the world) and the pressure on resources that the policy-fuelled population growth creates. Policy simply needs to change direction.

On a happier note, it is a year today since I left the Reserve Bank and was thus able to give this blog some publicity. In effect, it is the anniversary of the blog. I’ve really enjoyed almost everything about the intervening year – best of all has been the more time with my kids, whether that has been baking, blackberrying, watching US political debates together, or just ensuring that the piano practice is done, and not inflicting on them nannies or after-school care.

The blog itself has found more readers than I had ever thought likely, which in turn probably prompted me to put more into it than I originally envisaged. Somehow, I’ve read fewer books in the last year than I did in years when I was working fulltime. I wanted to say thanks to all the readers, regular and occasional, and to those who have commented. One of the best ways to refine one’s own thinking is to write, and be open to comment. I’ve learned a lot in the last year, and (yes, it happens) have even altered my views on some issues. Apart from anything else, one sees the world a bit differently once outside public sector bureaucracies.

Readership statistics aren’t always easy to interpret. Many readers just get posts by email, and most other just drop by the home page, not explicitly clicking on any particular post. But looking back over the last year, these are the 10 posts that have had the most people explicitly clicking on them, sometimes because they have been linked in other blogs.

- A post on how New Zealand has done, relative to other advanced economies since 2007

- A post on the proposal to extend the Wellington airport runway, using large amount of ratepayer’s money.

- A post on the June 2015 CPI numbers, which I saw as a severe commentary on the Reserve Bank’s conduct of monetary policy in recent years.

- A post looking at the occupational breakdown of our permanent and long-term migrants.

- A post prompted by Malcolm Turnbull’s declaration, on deposing Tony Abbott, that he wanted to emulate “the very significant economic reforms in New Zealand”. I noted that it was short list: I couldn’t think of any.

- A post on an unconvincing speech on housing by Reserve Bank Deputy Governor, Grant Spencer

- A post on financial crises around the advanced world since 2007.

- Another post on the occupational classification of our “skilled” immigrants.

- A post prompted by Wellington City Council meeting with local residents on plans to allow more medium-density housing

- A post on the continuing fall in dairy prices last year, with some longer-term perspectives.

Somewhat surprisingly, my post earlier this week about John Key’s apparent vision to turn New Zealand into a Switzerland of the South Pacific based on some mix of Saudi students, Chinese tourists, and wealthy people fleeing terrorism, is next on the list.

I’ve spent more time writing about the Reserve Bank itself than I ever intended. Mostly that was because of the Bank’s unexpectedly obstructive attitude to OIA requests, and the unexpected slowness with which they have recognized just how weak inflation has been (and is) in New Zealand. I hope to write less about the Bank in the coming year. My main concern in matters economic is the continued long-term underperformance of the New Zealand economy, and (relatedly) the disappointingly poor quality of the policy analysis and advice of the leading official policy agencies in New Zealand. The Reserve Bank is an important, (too) powerful, institution, but in the grand scheme of things central banks just don’t make that much difference, for good or ill. That was a message I spent decades trying to spread while I was inside the institution, although I’m not sure we were ever very successful in persuading outsiders. So I expect I’ll continue to make the point here. People looking for the answers for New Zealand’s economic problems shouldn’t be focused on 2 The Terrace, but instead should be looking to the other corners (here and here) of that Terrace/Bowen St intersection.