Hamish Rutherford had an article in the Dominion-Post yesterday in which he quotes the Prime Minister as claiming, on the one hand, that the recent high net migration inflows are a “time of great celebration” and, on the other hand, that most of the arrivals are something the country “can do nothing about”. Rutherford had a follow-up piece yesterday with some comments from me and from a couple of other economists – a nicely balanced group; one relatively negative, one relatively positive, and one “it depends”.

Actually, I suspect nobody much shares the Prime Minister’s glib “time to celebrate” sentiment. You can be as much a believer in more liberal immigration, or even open borders, as you like, but it still repays stopping to look at just why things are as they are. Ours isn’t that positive a story.

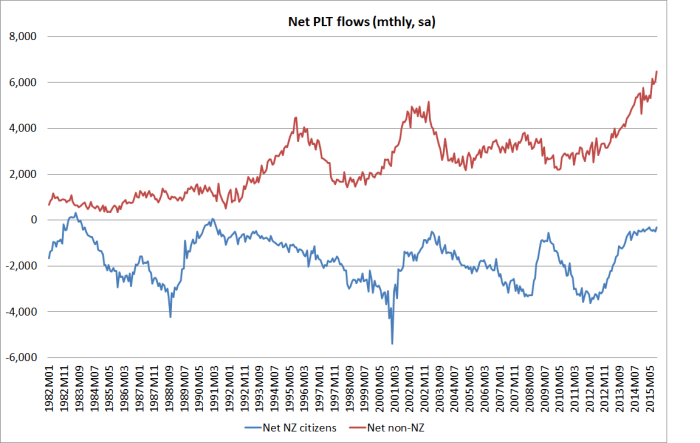

Of course, contrary to the headlines, the net inflows we’ve been seeing recently are not “record migration” in any meaningful sense. Yes, the net PLT inflow is at a record level, and perhaps even as a share of the population at any time in the last 100 years or more. But the limitations of the PLT numbers are well-known. If one looks instead at the total arrivals less total departures, the inflow over the last year has been around 60000. By contrast, in 2003 the annual inflow peaked at 80000. New Zealand’s population is now around 15 per cent larger than it was in 2003, so the per capita inflow over the last year or so has only been about two-thirds the size of what we experienced in 2003. So the current inflow is large, but not really at record levels.

And although the target number of residence approvals for non New Zealand (and non-Australia) has been 45000 to 50000 per annum for years (despite the growing population), only 43000 approvals were granted in 2014/15, compared with almost 53000 in 2001/02. I think MBIE even objects to the use of the word “target”, but however one characterises the number that Cabinet set, it isn’t met precisely each year. In fact, perhaps reflecting the relatively weak domestic labour market since the recession, 2009/10 was the last year in which residence approvals were above 45000.

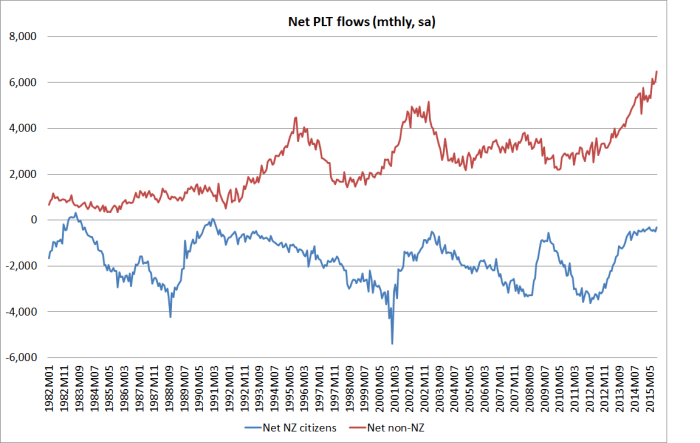

And can we control the total net flow numbers? Well, not really since New Zealanders are free to come and go, and of course any foreigners who has come here (needing advance approval) can also leave any time they like. Since the trough in 2011/12, the increase in the net PLT flow has been roughly evenly split between New Zealand citizens and other citizens, but over the last 18 months the decline in the net NZ outflow has levelled off, and all the further increase has been down to increased net inflows of non New Zealand citizens. At around 6500 in the last month, that net inflow probably is a record, even in per capita terms (SNZ don’t report the total migration data by citizenship). Every non-New Zealand citizen coming to New Zealand needs the approval of New Zealand authorities.

It is worth bearing in mind that there is still a net outflow of New Zealanders each month. The last times there were even modest inflows were 1983 and 1991, both occasions when Australia’s economy was in recession. Given that the stock of New Zealanders living abroad is now much larger than it was in either 1983 or 1991, it would have been easier to envisage a larger net inflow of New Zealanders this time if our economy and labour market were really performing well. But they aren’t. We can’t rule out a small net inflow of New Zealanders at some point, but it hasn’t happened yet.

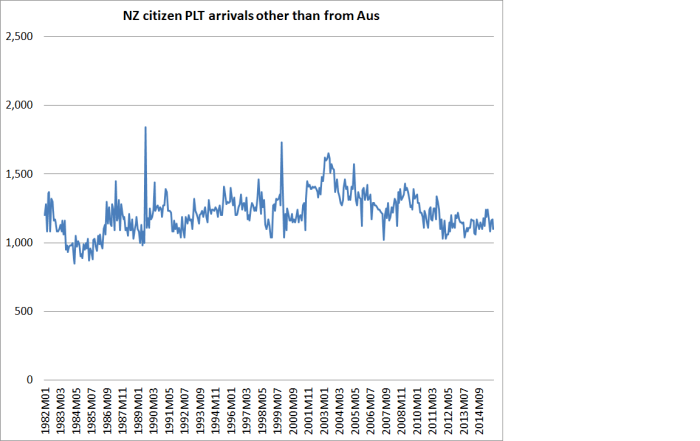

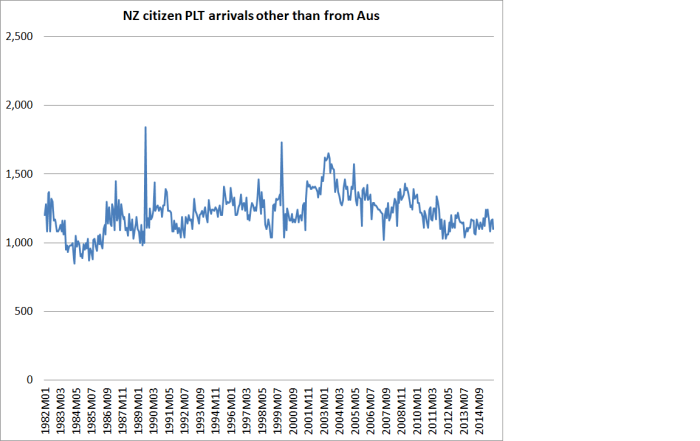

We can see the role that Australian conditions are playing by looking at the flows of New Zealand citizens to and from Australia, and the flows of New Zealand citizens to and from other countries. If the story were one of a strongly-performing New Zealand, I’d have thought we might expect to see New Zealanders flocking home from all corners of the globe (and not leaving for the rest of the world). New Zealand citizen arrivals for the rest of world (other than Australia) are at quite a low ebb – well below, for example, what we saw in 2003 when our unemployment rate was dropping sharply.

And New Zealand citizen departures to the rest of the world, while quite notably lower than they were in earlier decades (tighter restrictions in place like the UK?) have been pretty stable for the last six years.

Instead, all the action in the New Zealand citizen flows is in those between New Zealand and Australia, suggesting that it is conditions in Australia that are at the heart of the story.

The unemployment rate in Australia is around 6 per cent, and there is now a much greater awareness than previously that the rules in Australia have changed for New Zealanders. Any one going now, and who has gone in the last 15 years, is largely on their own if, for example, they can’t find a job, or they lose their job. And their kids are often in some limbo, not really New Zealanders and unable to become proper Australians either. Without that sort of welfare backstop if things go wrong, it is much more attractive than it was for anyone remotely risk averse to stay at home until the Australian labour market is much more robust. It may be less attractive to try even then than it once was. And that is so even though average incomes and real living standards in Australia are higher than those here, and that gap has shown no sign of narrowing. But it is not that to any material extent there is a net outflow of New Zealanders from Australia (although the uptick in New Zealanders coming home isn’t something we’ve seen before), it is simply that for the time being the outflow to Australia has dried up.

Given that the adverse income gap has not narrowed and that our unemployment rate is high, nothing in that is a cause for celebration in New Zealand. If anything, rather than reverse. The more highly productive Australian economy has been an attractive option for New Zealanders for decades – enabling New Zealanders to improve their lot (and taking downward pressure off factor returns in New Zealand). If that alternative outlet is less easy or safe to take advantage of, New Zealanders as a whole are a little worse off. If, for example, people relocating from Invercargill to Auckland were made ineligible for welfare benefits, Invercargill as a whole would be worse off economically – even though some of the parents in Invercargill might be pleased to have their kids and grandkids a bit closer to home.

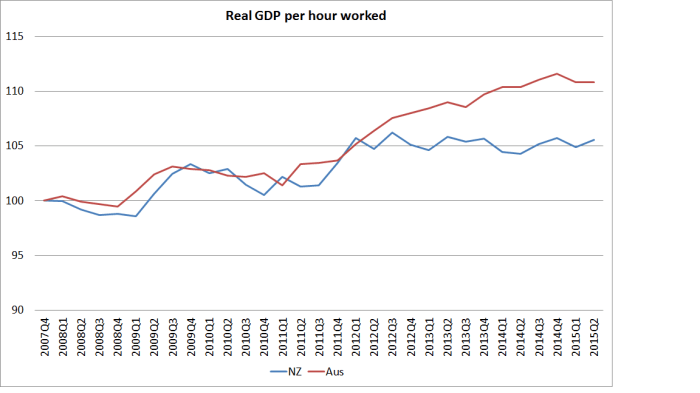

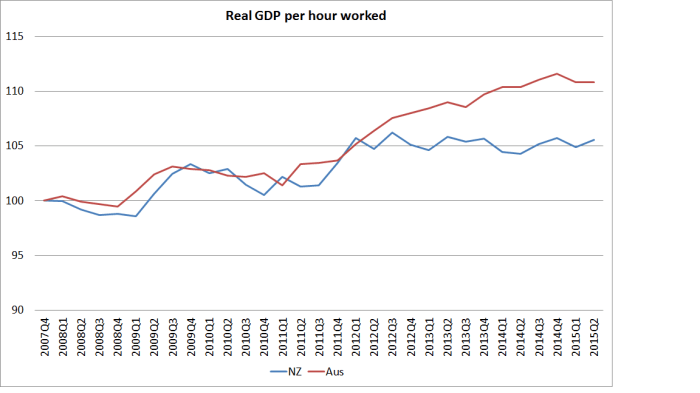

And what of New Zealand’s economic performance relative to Australia? Real GDP per hour worked is a pretty good timely measure of relative productivity performance . As the statistics stand at present – who knows what revisions will eventually show – the New Zealand performance in the last few years has been really bad by comparison with Australia’s. Data suggesting no productivity growth for four years, while Australia has gone on achieving productivity growth, just reinforces a sense that the reduced outflow of New Zealanders to Australia – partly temporary and probably partly permanent – is something bad for New Zealanders, not something to celebrate.

It needn’t always be so. I wish we had the sort of strong sustained economic performance, built on rapid productivity growth, that was putting us a path to income convergence (once again) with Australia. If so, I reckon we’d see the net outflow turn into a material sustained inflow. That would be cause for celebration. This is not.

And all that with barely any discussion of the non-New Zealander flows. But just briefly. The Prime Minister correctly notes that foreign students are an export industry. But I’d be more reassured by that if it were not explicit government policy to encourage foreign students, not on the intrinsic strength and quality of our own (middling at best) universities, but as a pathway to residence here. Since there is no evidence that such permanent immigration to New Zealand has represented a net economic benefit to New Zealanders – neither MBIE nor Treasury nor relevant ministers have been able to cite anything remotely convincing – it seems that we are really just back in the export incentives business. Instead of writing cheques, we write (the possibility of) a visa. Export incentives “worked” in the pre-liberalisation period to – people do what they are incentivised to do so we got more subsidised exports – but it still wasn’t good policy. It wasn’t under Muldoon and Rowling, and being done by Steven Joyce and John Key doesn’t change the proposition. I’m not, at all, suggesting we should discourage export education, but let it stand on its own merits if the current numerical success is really to be a cause for celebration.

The Prime Minister also reckoned that “many of the arrivals fell into either highly skilled or investor categories”. In the last year, just 1353 residence visas were issued under the investor and entrepreneur categories (about a third as many as were being granted in the early 2000s) and as I noted in an earlier post MBIE’s research has highlighted just how questionable the net economic benefit of these migrants has been.

One of the MBIE papers is on the web. It discusses some work on investor migrants – who already, in effect, buy their way into New Zealand. The aim of the programme is to import people with business expertise and entrepreneurial skills, presumably to boost productivity in New Zealand. And yet in these surveys of people at various stages of the investor migrant process (and in which respondents must have been at least partly motivated to give the answers MBIE wanted to hear, even if results were anonymised), 50 per cent of the money investor migrants were bringing in was just going into bonds, and only 20 per cent was going into active investments. We aren’t short of money, but may be of actual entrepreneurial business activity. And 70 per cent were investing only the bare minimum required or just “a bit more”. And these people aren’t attracted by the great business opportunities in New Zealand, but rather by our climate/landscape and lifestyle. It doesn’t have the sense of being a basis for transformative growth.

Set alongside the 1353 investor and entrepreneur visas were 4477 parent visas last year.

As for the highly skilled, I have covered previously and, in a succession of posts, at somewhat tedious length the question of just how highly skilled our skills-based immigration programme is. Here, from the tables in MBIE’s excellent resource, Migration Trends and Outlook, are the numbers for 2014/15 –the top few occupations for the principal applicants for residence applications under the skilled migrant stream.

| Chef |

699 |

| Registered Nurse (Aged Care) |

607 |

| Retail Manager (General) |

462 |

| Cafe or Restaurant Manager |

389 |

It doesn’t have a strong sense of something to celebrate – the highly skilled of the world flocking to New Zealand and in the process strengthening our own skills levels and productivity.

And finally, the Prime Minister is quoted as saying

“Show me a country which is booming around the world where more people leave it than come to it”

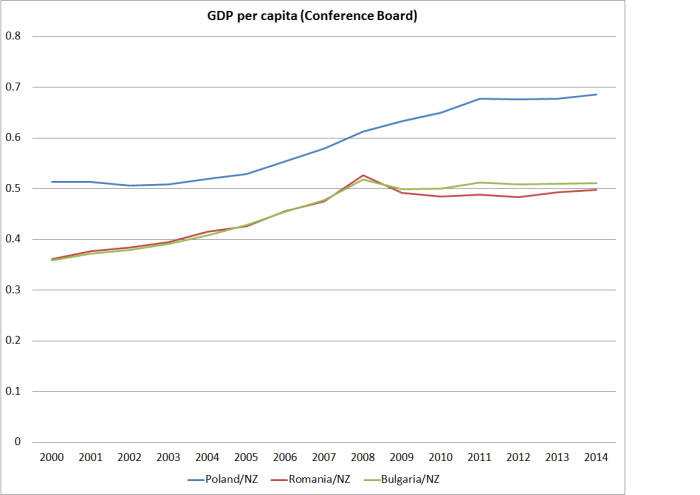

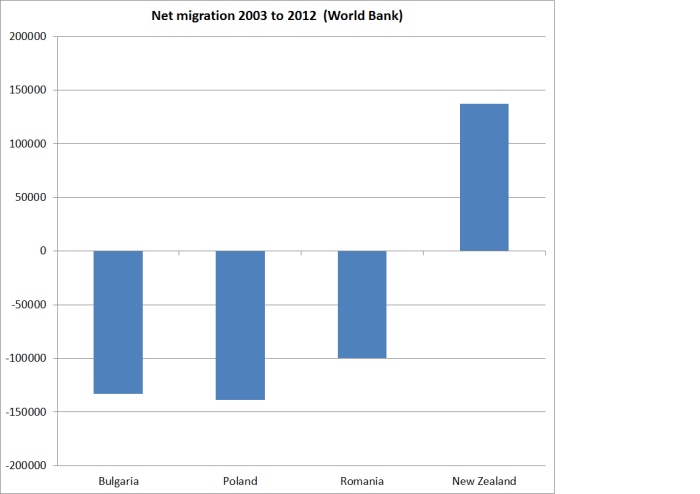

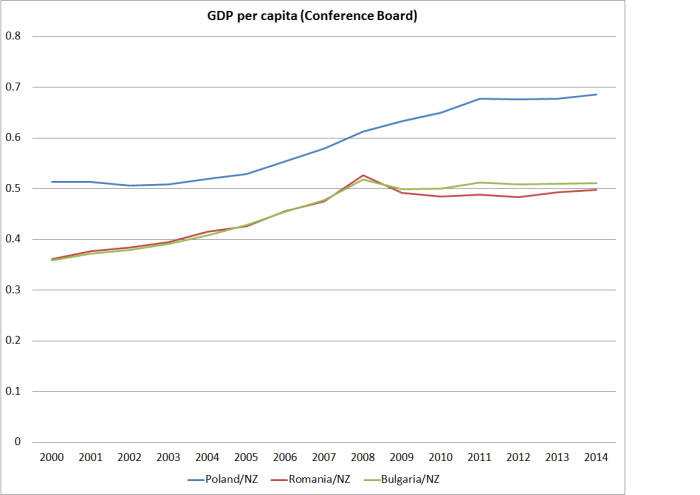

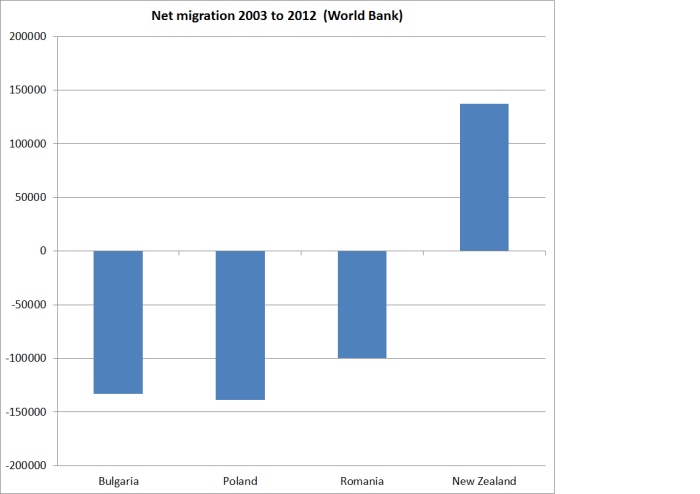

Glad to Prime Minister. Consider Poland, which has been one of the strongest performing OECD countries in the last decade, and which has had steady net migration outflows. Poland is gradually catching up to the living standards in Western Europe, but it has a long way to go. In the meantime, the opportunities for many Poles are still better abroad. Perhaps it is easy to dismiss Poland as just an ex-communist country, but it has done what New Zealand has failed to do – make substantial progress towards converging with living standards elsewhere in the advanced world. In 1989, Polish incomes were estimated to be less than a third of those in the United States. Now they are almost half.

Bulgaria and Romania are less striking stories, but they are also countries with substantial net migration outflows – again, the opportunities abroad are better than those at home. But both countries have managed to grow materially faster than New Zealand since 2000, and have matched New Zealand’s per capita income growth in the years since John Key has been in office.

Immigration policy is not, by any means, the whole story. It probably isn’t even the bulk of the story in these countries. But net inflows of people aren’t always good and net outflows aren’t always bad. It depends. There is no real reason to believe that the current net inflows to New Zealand – or even the reduction in net outflows to Australia – are cause to celebrate. I suspect that, if anything, the inflow is compounding the underlying productivity problem. But there is certainly no sign that it is either a response to us having solved those problems ourselves (and thus being on some convergence path back to the rest of the advanced world) nor that the inflow will be any more likely to bring about a transformative lift in productivity than the previous inflows over the last 25 (or 75) years have.