At 6 per cent, our unemployment rate is no longer low. And yet it seems to excite little interest, whether from the media, economic commentators, the Reserve Bank, or the government.

I’ve argued that the Reserve Bank’s unnecessarily tight monetary policy over recent years (as revealed by core inflation outcomes) has contributed to the high unemployment rate. Within a standard model, this shouldn’t be a remotely controversial claim. If, as the Bank reckons, inflation expectations are in line with the target, then actual core inflation outcomes persistently below target will have reflected less utilisation of productive capacity (labour and perhaps capital) than would have been possible. Put that way, it sounds bloodless and technocratic, but real people are affected here – people unable to get a job at all, or to get as many hours as they would like. Lower policy interest rates would have stimulated some more domestic demand, and would have lowered the exchange rate, stimulating some more external demand. And core inflation would have come out nearer the target.

I’m not going to repeat the debate as to whether, with the information they had at the time, the Reserve Bank could reasonably have run a different stance. I think so, and said so in writing within the Bank at the time. But the point here simply is that, at least with hindsight, monetary policy was persistently too tight, and there has been an output and unemployment cost to that – in a recovery that was, in any case, probably the most anaemic New Zealand has had for a very long time. And the cost goes on – even now, the unemployment rate is rising, not falling.

But how do we compare? I downloaded the OECD data on unemployment rates for the 19 OECD monetary zones (ie 18 countries with their own monetary policy, plus the euro area).

Despite having some of the more flexible labour market institutions among advanced countries, New Zealand’s unemployment rate, at 6 per cent, is currently a bit above the 5.5 per cent median for this group of countries.

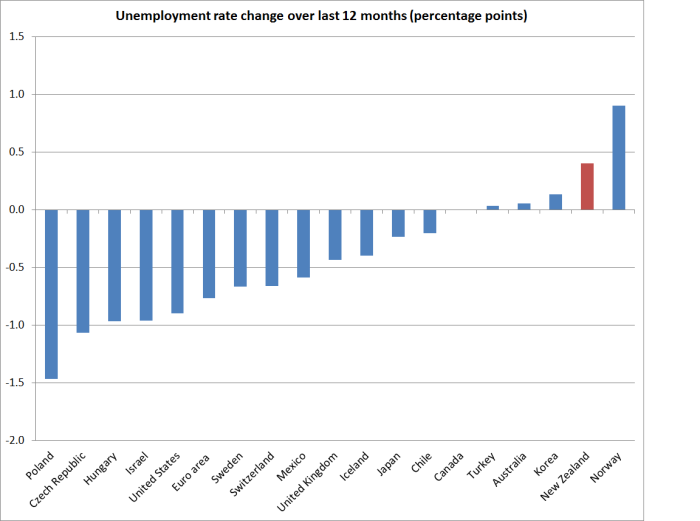

And over the last year, only four of these countries have had an increase in their unemployment rate at all. New Zealand’s increase has been second only to that in Norway. The last year has been tough for Norway, with the collapse in oil prices. The central bank has cut interest rates, by 75 basis points. But they are somewhat constrained. The inflation target in Norway is 2.5 per cent, and core inflation is at least that high. The central bank lists four core inflation measures on its website: one is at 2.4 per cent, one at 2.5 per cent, and the others at 2.8 per cent and 3.1 per cent. Each of those measures is higher than they were a year ago. Without looking into Norway in more depth, the rise in the unemployment rate (which is still only 4.5 per cent) doesn’t look like something that monetary policy can usefully do much about. New Zealand is different.

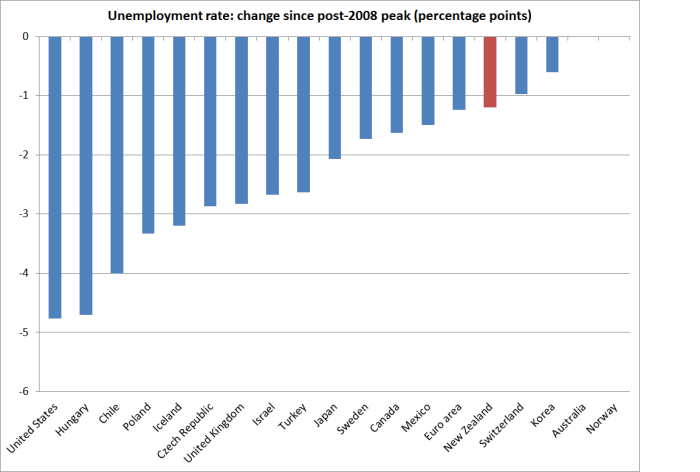

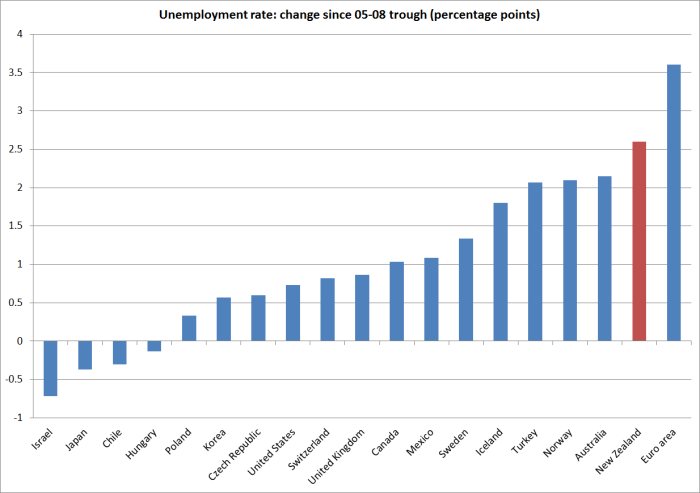

New Zealand also shows up at less attractive ends of the charts if we look at how the unemployment rate has changed since either the peak reached in the recessions from 2008 on, or from the trough in the boom years. On the latter measure, the only area that has seen more of an increase in the unemployment rate is the euro area as a whole (which has pretty much exhausted the limits of conventional monetary policy). And it is not as if our boom was extraordinarily large – using OECD estimates, our peak output gap in the boom years (3.2 per cent) was bang on the median for this group of countries.

So New Zealand’s outcomes look pretty bad. Relatively high unemployment now in cross-country comparisons, rising unemployment, and by some margin that largest increase in the unemployment rate since the boom years of any country that still has conventional monetary policy capacity left. It should be a fairly damning indictment.

Of course, Australia also shows up towards the upper end of each of these charts. Each of the RBA’s core inflation measures is now below their target, although (a) by less than core inflation is below target in New Zealand, and (b) this gap between outcomes and target has only really emerged in the last few quarters. By contrast, core inflation in New Zealand has been clearly below the target midpoint for more than five years. I suspect the Reserve Bank of Australia should also be cutting their policy rate further, but at present any error there looks less egregious than the error in New Zealand.

(Defenders of the Reserve Bank could, of course, reasonably point out that the Bank has cut by 100 basis points this year, and that monetary policy works with a lag. However, since the Bank forecast yesterday that the unemployment rate will still be 6 per cent in March 2017, and inflation then is forecast to be only 1.5 per cent – even with a material acceleration of growth – that point is not particularly telling on this occasion. It simply means that this year’s cuts have stopped the situation getting even worse.)

I’m not entirely sure why the unemployment outcomes seem to be getting no traction in the New Zealand debate. Perhaps there is something in the insider/outsider story – neither the bureaucrats making policy nor the market economists commenting on it are unemployed. And perhaps many of them are, like me, of an age that the 11 per cent unemployment rates in the early 1990s shaped their perspective? And having spent much of his career abroad, mixing mostly with international agency elites, the Governor may also have a rather limited degree of identification with the New Zealanders at the bottom end who are paying the unemployment price. But none of this seems particularly compelling.

As is widely recognised, the main Opposition political party has been failing, and isn’t helped by having a finance spokesperson who seems to struggle to get to grips with the issues, and to communicate them in a way that either resonates outside central Wellington, or in the House. And yet, the unemployment rate would seem to be a natural issue for the Labour Party, with its strong union base, and voter base among the relatively less well-off sections of the community.

I suspect the Minister of Finance isn’t very happy with the Bank’s handling of things – he has hinted as much in several public comments earlier in the year. But what is in for him to make more of the Reserve Bank’s failing? The government’s popularity ratings remain high, and the media and business elite continue to retail a narrative in which New Zealand’s economy is doing just fine – despite near-zero per capita GDP growth, almost non-existent productivity growth (and high unemployment).

Which leaves me wondering whether elite opinion support for large scale immigration – repeated yesterday by the Reserve Bank Governor – is part of the story. The Reserve Bank reckons that the high rate of immigration has raised the unemployment rate and lowered wage inflation – it is there in the text of the MPS yesterday. I reckon they are wrong on that: the demand effects of immigration surprises have almost always outweighed the supply effects, and so surprisingly high immigration has, if anything, tended to hold the unemployment rate down in the short-term (in the long-term it is the labour market institutions that determine it). If you really strongly believe in the benefits of high rates of immigration to New Zealand – and that has been the elite view, against the evidence of a steady trend decline in New Zealand, for a century or more – but think it is raising the unemployment rate in the short-term, then you might be reluctant to express any serious unease about the high and rising unemployment rate, lest it cast doubt on your preferred immigration policy. If there is anything to that interpretation, I’m sure it is subconscious rather than conscious. And I’m not sure if it explains anything either.

This is one of those times when central bank independence is not really serving the interests of New Zealanders. The logic of the argument was that independent central banks would protect us from high inflation. Now it is working the other way round. If the Minister of Finance were making the OCR decisions, the political pressure to do something about rising unemployment – at a time of very low inflation – would probably be more focused and intense. The Minister of Finance has to face questions in the House every day, and make himself regularly available to the media and voters. By contrast, the Governor hides away behind a cloak of technocratic expertise, and a Board which sees its role as to protect and promote the Bank. That means no effective accountability (remember, real accountability means real consequences for real people).

He also said nominal wages had been strong, but when I went to look it up it said only +1.6% for the year to Sep.

LikeLike

yes, altho that is the LCI – which is a proxy for a unit labour cost measure. The “analytical unadjusted” LCI series they also publish is more like a raw index of wage growth and that is around 2.7% – but not showing any sign of accelerating

LikeLike

As I thought about the Governor’s presentation yesterday as a non economist it seemed that the majority of the delivery was about negatives. If the Auckland housing market strengthens we increase the cash rate, If consumers borrow and spend more we … If inflation expectations increase we …

There was no mention of getting the economy to perform at an optimum level. No mention of improving New Zealanders standard of living, No mention of ways to improve productivity. No mention of reducing unemployment. The delivery seemed to be inward looking. About the problems the bank had in setting the cash rate so it looked good in the eyes of those that comment on the banks performance. I thought the Governor was paid to do the best for us, ordinary Kiwis.

P.S. Why does the Governor need the chief economist sitting beside him, referring questions to him and having him hold his hand. Is the Governor not paid enough or knowledgeable enough to face a few media hacks ?

LikeLike

Alastair

So now (poor as I thought the performance was yesterday) I’m going to stick up for the Bank. Monetary policy can’t do much about the things you (reasonably) worry about – it can affect inflation (permanently) and the unemployment rate and state of the economy in the short run but for the longer-term stuff you need to be looking to the political leaders (and perhaps their Treasury advisers). So I’d say the Governor is paid to do the best for ordinary NZers, but mediated through the PTA (ie it isn’t just his judgement about what counts as “best”) but he has tools that let him do and important, but rather limited, job.

Re having the Chief Economist there, the original logic was mostly just to allow very technical questions to be deferred to the technical expert (there are a lot of numbers in those statements). But I was surprised by just how often the Governor invited the Chief Economist’s comments. I suspect it is a mix of wanting to look open/inclusive (not just a “one man band”, and his own lack of confidence in dealing with the media. He is a professional technocrat, and in his day was quite a well-regarded one, but that is a different set of skills that articulating a case to the wider public, and responding to the issues and questions that concerns them and the journalists – different issues often, and certainly a different language, than the econo-speak (or bureaucrat speak) he has spent his working life with. Some can make the transition well. Others not so much.

LikeLike

Thanks Micheal, just one last comment, I was suprised he mentioned a number of factors that he thought might lead to increased inflation or the need to increase the OCR but then suggested the Government should increase infrastructure spending. My question, are we in danger of the economy over heating, stagnating or do we not know ?

LikeLike

Honest answer is “we don’t know” (margins of forecasting uncertainty are too great) but I think the risk is clearly skewed towards the stagnation side, and see very little chance of the economy overheating (if it didn’t when the terms of trade were at 40 year highs, and the Chch rebuild was ramping it, there is very little chance of it now.

LikeLike

Maybe the lack of focus reflects political economy dynamics. If I have read the numbers right (big ‘if’), the unemployment rate is much higher in the 15-34yr age cohort relative to those beyond 35yrs. And then looking at voter turnout by age group for the 2014 general election, those below 35yrs seem less enthused about parliamentary representation relative to those +35yrs and it looks like when you hit +50yrs, you start to take politics very seriously as this group accounted for half of all voters at a turnout rate of 85%! So, what do you do if you want to stay in government? Maybe: keep house prices up, wages low to limit service inflation and for the younger ones, roll out broadband for social media distraction (guilty as charged!) and if you want to buy your first house but are having trouble saving for a deposit ,no problem, the government is here to help with a 90% LTV scheme. But, end of day: onus is on the younger ones to vote….!

LikeLike

Perhaps there is something to that – but then youth unemployment rates are always higher than those for older age groups, and every one of them is someone’s child.

Another possibility: according to the HLFS the unemployment rate among Europeans is 4.1%, while among Maori it is 14.6%, Pacific 12.6% and among “Maori/European” 10%. Mostly not the demographic for the current government. But then where is the Opposition?

LikeLike

….on ‘twitter’? haha. To be fair, Mr Little did set out his three top priorities as “jobs, jobs, jobs” in his conference speech, though, devil in details I guess (and the thorny issue of big government v big business…..)

LikeLike

this is a case of supply side mathematics models trying to resolve aggregate demand problems the governor’s second in charge is s man with a hammer who only sees nails

LikeLike

Michael, I applaud your efforts in turning up the heat on the governor.

However, recovery from the GFC, in the countries where it has happened, has mostly been exceedingly slow — it’s not peculiar to New Zealand!

To grow an economy takes an increase in demand from consumers, because it leads producers to not only produce more but also to invest to produce more.

That means that both consumers and producers need more money to spend, But the only way they can get more money is to borrow it, but as they generally consider themselves to be too indebted already, they’re generally not willing to take on more debt, even at the present, historically low interest rates — except to buy houses — hence the house price asset bubble in Auckland and spreading outwards to hamilton and Tauranga.

The housing bubble has seen the average house in Auckland, where a third of New Zealand’s population resides, go from 3 times the average income to 9 times the average income in around thirty years. Money that consumers spend on servicing their mortgages is money that they haven’t got for spending on consumer goods and services, and many of them are very wary that the present low interest rates may not last for much longer.

As proponents of a Sovereign Money banking and monetary system (www.sovereignmoney.eu and http://www.positivemoney.org and http://www.positivemoney.org.nz), such as myself, keep reminding anyone who will listen, many economies have finally reached the point where people are now so indebted that very few people want to take on any more debt, and hence the economy is not growing very fast, if at all. Rising unemployment is evidence that the economy has spare capacity, but lacks money to drive expansion.

In a Sovereign Money system, new electronic money with which to expand the economy would be created by the RBNZ and gifted to the government free of interest and free of debt, for the government to spend into the economy according to its democratic mandate, at a rate to just keep the rate of inflation as close as possible to the middle of whatever target band the Minister of Finance sets. If it was 1% – 3% as at present, the RBNZ would be creating about $12.5 billion p.a. and government could reduce its total annual taxation take by that amount, leaving the people with that much more to save, invest, or spend — it would be our choice as to what proportion of our extra money went on each. Hence the economy could grow without people having to go further into debt.

In a Sovereign Money system, a law change (draft legislation is on the Positive Money websites) would ensure that banks became financial intermediaries — moneylenders — that take in money from savers, aggregated it, and lend it to borrowers, making an honest profit from the margin between the respective interest rates. Banks have always maintained that this is what they do anyway, and it is what all students of economics — at secondary schools, polytechnics and universities — are being taught that banks do. There would be only one kind of money — sovereign money — and debt-money created by banks making loans — which makes up 98% of the money supply — would be phased out, as it would become unnecessary and would be inflationary.

Booms and busts would become almost non-existent, as would asset bubbles.

LikeLike

Booms and bust, optimism and pessimism, are embedded pretty deeply in the human psyche I’d have thought. I’d be surprised if a mere reform to the monetary system really changed that very much (altho such reforms can affect things at the margin). And, yes, I know I have promised a post on why I’m sceptical of the Sovereign Money ideas.

LikeLike