Following my post on Saturday about macroeconomic policy options, a reader posted the following substantive and interesting comment, which I thought warranted more of a response than a few lines buried in the comments.

The fiscal advice you propose is consistent with mainstream new-Keynesian models. This is the sort of outcome you get from the IMF modeling of the impact of a tighter fiscal stance in NZ in 2010 WP 10/128.

However, all these models assume that central bank acts rapidly and forcefully and is able to return inflation to target and output back to potential in short order (12-18 months or quicker because they assume that the monetary policy maker has a model of the economy that tell it in advance where output will be with certainty). This has not been the case. It is now 6 years since inflation has been at target and output at potential.

In these circumstance looser fiscal policy in the past (all else being equal) would have lead to high output, lower unemployment and inflation closer to target. All around welfare is higher. Perhaps we should leave aside the issue of what the fiscal policy maker should do if they share your beliefs about the RBNZ meeting its future target. Although just for the sake of playing devil’s advocate it would seem to me to be hard for the central bank to react to a fiscal loosening in this situation in the same way they might at close to full employment and their inflation objective.

Just looking at the near term it appears to me we face the risk of fiscal policy again being contractionary (perhaps only mildly) at a time when output is below potential – and fiscal policy will again be pro-cyclical.

Now there might be a good reason for all this if NZ was struggling with a large public debt burden and had no history of delivering fiscal consolidation. Yet this is not the case on either count. If you look at the IMF fiscal number and look at the change in primary balance (I used a 3 year average over the crisis period compared with calendar 2015) you will find that NZ adjustment (~ 7.5) looks like around the level of Portugal and Spain and Greece (Ireland is off the chart because of the size of the fiscal support provided to the banks through the accounts in these years). This is all in the context of macro models that suggest the appropriate pace of debt reduction from once in a generation shock is slow…..

And what about commodity prices?. I think the way to think about this is that you might tell you something about the right level of structural balance to aim for abstracting from the cycle. In my humble opinion it cannot tell you too much about the right fiscal stance from a cyclical point of view. To see this just imagine that this approach would have suggested a rapid tightening of the fiscal stance in 2010 as commodity prices returns to their peak despite the economy being in a deep slump. Another way to see this is to look at the cyclically adjusted balance scenario with the terms of trade at their 30 year average – this suggests that the structural balance is 2.5 percent worse than the forecast in every year.

Lastly, the decision needs to be made under the knowledge that the outcomes are asymmetric. If the central bank does its job as the macro models predict then we get a slightly different mix of output. But output reaches potential – no harm no foul. On the other hand if this is not the case then the outcome of looser policy will be much like I describe above for the past 5 years – higher output, employment, and welfare. All without reference to the risks of deflation or the zero lower bound.

There are a number of different points here.

I had noted that if a tighter fiscal policy had been adopted over the last few years that should have eased pressure on demand, the exchange rate and the OCR. But as the commenter points out, it has been quite some years since core inflation was at target, and output also appears to have been consistently below potential (at least judging by the unemployment rate, if not by eg the Reserve Bank’s output gap estimate).

If so, mightn’t a looser fiscal policy – as suggested by Brian Fallow – have delivered some better economic outcomes? I don’t think so. The repeated mistakes the Reserve Bank has been making over the last few years have not had to do with fiscal policy. The Bank’s approach is simply to take announced fiscal policy – Treasury’s own numbers – and build those assumptions into its own economic forecasts. Internally, I was sometimes critical that we were too willing to base policy on government promises – which is all forward operating allowance estimates are – but in recent years doing so hasn’t provided a misleading steer. The government got the Budget back to balance roughly when it said it would.

All that means that, as they said they were doing all along, the Reserve Bank set the OCR a bit lower than they otherwise would have because of the fiscal adjustment that was promised (and delivered). Had the government planned a slower pace of fiscal consolidation, the Reserve Bank’s demand and inflation forecasts would have been a little stronger, and the case for tightening in 2013 and 2014 would have appeared even stronger to them than in fact it did. The mistakes were about how the economy was working, not about the government’s own fiscal actions.

Only if fiscal policy had been surprisingly loose (unrecognised by the Reserve Bank) might there have been some windfall macro gains – output a bit higher and inflation nearer target. But no one wants to go back to a world of non-transparent fiscal policy – perhaps especially not where one part of government (Treasury) keeps fiscal actions secret from another part of government (the Reserve Bank).

The commenter suggests that “we face the risk of fiscal policy again being contractionary (perhaps only mildly) at a time when output is below potential”. The PDF with the supplementary Budget information on the Treasury website won’t open so I can’t check the fiscal impulse etc numbers, but two thoughts (a) surely any contractionary discretionary fiscal policy over the next few years must be pretty mild? and (b) whatever is flagged in the Treasury numbers is already included in the Reserve Bank’s forecasts and policy. Since we are still nowhere near the zero lower bound, it seems unlikely that any additional fiscal contraction over the next couple of years will be holding back economic activity or inflation. The Governor can fully offset the effects of well-signalled, relatively modest, fiscal actions.

I had made the point that the Budget had been flattered over the last few years by the high terms of trade. If anything, I argued, a case could be made for having got back to balance a bit sooner than the government chose to. After all, as Treasury’s numbers show, if one redid the fiscal numbers with the terms of trade set at their 30 year average, there would still have been a material (although not unduly alarming) deficit even in 2014/15. My commenter seems to see this as an argument against faster tightening, but I don’t quite understand why. A rising terms of trade does not of itself argue for faster discretionary fiscal consolidation, but rather for recognising that much of any improvement in the reported conventional cyclically-adjusted balance estimates is just arising from the boost to the terms of trade, and the underlying extent of adjustment still required remains as large as ever. The improvement in New Zealand’s fiscal position has been flattered by the impact of the terms of trade.

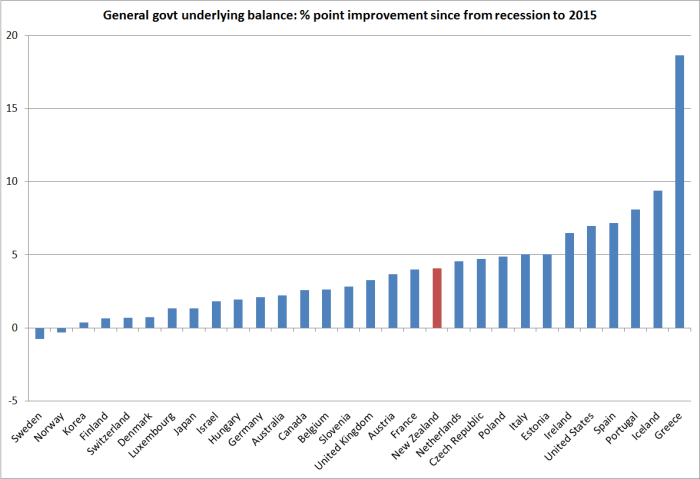

Judging how much fiscal consolidation there has actually been is more of an art than a science. My commenter presented one set of numbers, which suggests that there has been a very substantial fiscal consolidation in New Zealand in recent years, even by comparison with some of the benchmark austerity countries like Spain and Portugal.

I’ve got an alternative take, using the OECD’s underlying balance measure – which is both cyclically-adjusted, and removes identifiable one-off items (eg bank recapitalisation s in a single year, or earthquakes). Since the most recent OECD numbers are a few months old, the numbers aren’t quite as up to date as the IMF ones, but it is unlikely that the picture would change very much with a few months extra data.

Here is the increase in underlying surplus (reduction in the underlying deficits) as a per cent of GDP, from the low point reached over 2008 to 2010 to the latest 2015 estimate. Over that period, the median OECD country reduced its underlying fiscal deficit by 3 percentage points of GDP, while New Zealand’s adjustment was 4.1 percentage points. But New Zealand’s numbers were flattered by the fact that we had among the strongest terms of trade of any OECD country over that period. If that were corrected for, the extent of our fiscal adjustment would be even more unremarkable, and much less than those in Ireland, Iceland, Portugal, Spain and the US. And, of course, over that period our debt has increased.

It is quite reasonable to argue that New Zealand was under no particular market pressure to have adjusted that fast (neither was the US). But on the other hand, unlike all these countries other than Iceland, we still had plenty of room for conventional monetary policy to offset the short-term demand effects of contractionary fiscal policy. And although New Zealand did not use fiscal policy actively to counteract the 2008/09 recession (unlike the US, UK, or Australia, for example) it is worth reminding ourselves how large the deterioration in New Zealand’s underlying fiscal position was: on this underlying balance measure, only Spain and Iceland saw a larger fall in the underlying surplus from years just prior to the recession to the recessionary low. Fortunately, we had started from large surpluses.

In making choices about fiscal policy now, the effects are not asymmetric. The Reserve Bank will offset any discretionary fiscal easing now – the revised assumptions will feed straight into the forecasting models. We won’t end up with higher output, higher employment, or higher inflation, we’ll just end up with slightly higher (than otherwise) interest rates, exchange rates, and public debt (and temporarily higher spending or lower taxes). It is only when conventional monetary policy has reached its limits (say, an OCR at -0.5 per cent) that discretionary fiscal policy is likely to play a useful stabilisation role. And we provide the best chance of that being a politically viable and economically credible option, for the several years of stimulus that might then be required, if the government keeps a tight rein on fiscal policy now. I don’t favour running large structural surpluses in boom times – it is a recipe for fiscal splurges of the sort the 2005-08 government took. But adverse shocks are inevitable from time to time, and one of the best ways to cope with them is to keep public debt very low, and ensure that the budget runs modest structural surpluses in the more normal times. Even then , a severe adverse economic shock may well undermine tax revenue sufficiently that there will often be surprisingly little discretionary fiscal leeway.