It is a big few weeks for the Reserve Bank and, in particular, the Governor. This week the Monetary Policy Committee is gathering for its deliberations leading to next week’s Monetary Policy Statement. A couple of weeks later there is the Governor’s six-monthly Financial Stability Report, and the week after that we are told that the Governor will descend from the mountain-top and reveal his decision on bank capital. There are at least two press conferences scheduled (MPS and FSR) and given that he has deliberately chosen to release the momentous capital decision only after the FSR press conference one has to hope that he will make himself available to explain and defend his choices (and, although he has staff, all the decisions – and responsibility for them – are his alone).

Meanwhile stories rumble around about the possibility that the Bank’s Board has,for once, found its voice and suggested to the Governor that he needed to change his style. I heard yesterday another version of a story that culminated in the Governor yelling at the chair of the Board after the latter (so it was reported) suggested that aspects of the Governor’s conduct were unacceptable. I have no way of knowing whether these stories are true, or are just wishful thinking, but given the quiescent and deferential track record of the Board over many years, it would be perhaps a little surprising if there was nothing to the stories now.

One of the other projects the Reserve Bank has underway, which attracts less attention and controversy, is that around the future of cash. It is both an apt issue to be focusing on and, at the same time, something of an odd one. And, remarkably, in the discussion document the Bank put out a few months ago there was no mention – at all, as far as I can see – of the most immediately pressing issue: the limits on the ability to cut the OCR that arise because of the (near) free option people have to shift from bank deposits etc to physical cash.

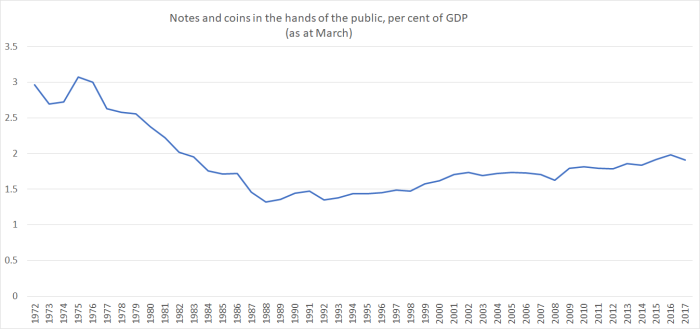

The future of (physical) cash is somewhat of an odd issue to be focusing on because cash outstanding has been rising relative to GDP. This chart is from the Bank’s discussion document

It tends to exaggerate the point, by starting from the trough. Here is a longer-term chart from a post I wrote on these issues a while ago

All else equal, when interest rates are very low (and inflation is low too) people are more ready than otherwise to hold on to physical cash. Of course, quite who is actually holding the cash, and for what purpose, is a bit of a mystery, one not really addressed in either the Bank discussion document or in the poll results they published last week, framed in terms of a high preference for using electronic payments media whenever possible.

The Bank included an interesting chart in its document illustrating that although the ratio of cash to GDP is quite low in New Zealand, the rise in that ratio wasn’t out of line with what has been seen in quite a few other advanced countries. Sweden and Norway – where the ratios have fallen – are outliers.

There is quite a strong suggestion that in the most recent period a big part of what is holding up currency in circulation was the surge in overseas tourism, especially from China.

Overseas tourism remains one of the areas where physical cash is much more likely to be used than in normal domestic spending.

Notwithstanding these routine and entirely legitimate uses of physical cash, it is still hard not to conclude that a large chunk of the physical cash on issue – in excess of $1000 per man, woman, and child – is held to facilitate illegal transactions, including tax evasion. That was Rogoff’s view, and as I wrote about here he – against my priors – converted me to that way of thinking.

So there would seem to be no risk of cash disappearing from the New Zealand scene any time soon. And yet the monetary policy constraint arguments, that the Bank simply doesn’t address in its discussion document, suggest that if anything the use of Reserve Bank cash (and especially the potential use of cash) should be constrained more tightly than at present. The Governor may repeatedly assert that unconventional monetary policy options will do just fine, but few other people would look at the international experience of the last decade without thinking that monetary policy ran into limits. Those limits arise mostly because of the non-interest bearing nature of the cash and the near-free option of converting into physical cash if returns on other short-term securities go, and are expected to stay, materially negative.

This limit need not exist, or at very least could be greatly eased. Abolish the $100 note, for example, and at very least you double physical storage costs of secure large cash holdings. Abolish the $50 note and you more than double the costs again (while the ability to give your kids pocket money in cash, or to use cash at the school fair isn’t materially affected). That was, basically, Ken Rogoff’s argument in the US (restrict central bank notes to no more than $20 bills). I’ve argued for one of a range of more-wholesale solutions that have been proposed: put a physical limit (perhaps indexed to nominal GDP) on the volume of currency in circulation (perhaps with overrides for bank runs), and auction the right to purchase new issuance (there is no reason why newly-issued cash has to trade at par). Do that – perhaps even set the limit fairly generously – and the effective lower bound, as a convertibility risk issue, is abolished at a stroke.

This is coming close to being a fairly immediate issue. No one supposes the Reserve Bank could, on current technologies, usefully cut the OCR by 200 basis points or more in a new recession, and yet in typical New Zealand recession something more like 500 basis points has been required.

It is pretty staggering that they haven’t addressed these considerations at all in their document. Instead, having had submissions (lots of them) on the first consultation document, they issues another consultation document (deadline for submissions tomorrow) bidding for more Reserve Bank powers over the currency system.

The currency system seems to have rubbed along tolerably well for the 85 years since Parliament gave the Reserve Bank a statutory monopoly on the issuance of bank notes (it seemed to function just fine in the earlier decades as well: whatever the case for setting up a Reserve Bank there was never a robust case for the statutory monopoly on bank notes).

But none of that deters the Reserve Bank. It is a rare bureaucracy that looks to shrink itself, or is averse to an expansion of its powers, and the modern Reserve Bank seems to be no exception. This is their bid

As they note, there is no need for any such powers at present. Which really should be determinative. It isn’t like preparing for an extreme national disaster, where it makies sense to have some precautionary powers on the books. This is about a payments media that is gradually being used less and less (for payments) and where change is exceptionally unlikely to happen overnight. Were there ever to be severe problems, surely Parliament could address such issues when they arose, rather than inventing new laws now – and delegating the use to unelected, not very accountable, officials – just on the off chance?

There should be a strong pushback against this bid for power. Their (short) document makes no compelling case for legislative action – and more discretionary regulatory power – now. Indeed, as they note

There is a host of international examples where cash system participants have found different solutions to fit their unique economies.

It is what the private sector does – innovate in response to market incentives and opportunities. They worry – as busy bureaucrats will – that “no single organisation has system-wide oversight of the cash system or a formal role to support it”. There is no such organisation for, say, the corner dairy sector either. Nor an obvious need for one – let alone for the government to be taking charge. They complain that they don’t have information gathering powers over participants who aren’t banks, but offer no analysis or convincing demonstration as to why they should have such powers.

They offer no analysis either as to why the market could adequately manage issues around ATMs or other processing machines, or even for the quality of the notes retained in circulation. Much of it seems to be made up on the fly – so it seems, to catch the decisionmaking process around other changes to the RB Act. Thus they talk of powers to compel banks to distribute cash, but seem to have thought through very of this bid for power for hypothetical circumstances. This, for example, is the last substantive paragraph of the document.

How accountability would be defined under such regulation, and therefore how sanctions could be applied, warrants further consideration. Banks could be held collectively accountable for the provision of cash services, meaning that banks would share the responsibility for providing access to cash, and all banks within scope would face sanctions for each case of noncompliance. This would be a novel regulatory structure in New Zealand, but might be practically workable and might encourage greater cooperation among banks. Alternatively, each bank could be individually accountable for the provision of certain services in certain areas. However, this presents challenges around how accountability is allocated. Both options present considerable practical challenges, which will need to be investigated in consultation with relevant parties if any policy is developed.

Doesn’t exactly instill much confidence.

Many of the problems the Reserve Bank worries about (perhaps arising one day) would, in any case, largely be a reflection of the statutory monopoly on banknotes. So perhaps a better legislative route would be to look at repealing that restriction – simple one clause amendment to the Act would do it – and allow banks to issue their own notes. Perhaps it is now a little late for that, but we don’t know if we keep on ruling out the opportunity for innovation. It might be considerably cheaper for banks to issue their own notes (as they issue their own deposits) – since they wouldn’t have to worry about returning them to a central point for value – and, conceivably, technological innovation might even allow interest-bearing bank notes (it is the zero interest nature of the existing notes that creates the lower bound issue for monetary policy).

Bids for new regulatory powers are often a response to issues, problems (or possible future risks) thrown up by existing regulatory or legislative interventions. The Bank’s latest bid for more discretionary powers seems exactly in that class of bureaucratic initiatives. The Minister of Finance should say firmly no to this latest bid, should insist on the Bank openly addressing the effective lower bound issue, and might consider asking the Bank what public policy end – other than higher taxes – is served by maintaining the 85 year old monopoly on note issuance. We got rid of most statutory monopolies a long time ago.