I haven’t followed the CBL saga very closely at all. (Disclosure: until the end of 2014 I was a member of the Reserve Bank’s Financial System Oversight Committee, which advised the Governor on prudential policy matters, including insurance prudential supervision. That Committee rarely dealt with individual institution issues, but nonetheless was part of the overall atmosphere around the Bank’s approach to regulatory and supervisory issues.)

But the one aspect of the CBL story I had paid attention to was the decision by the Reserve Bank in 2017 to ban CBL from telling shareholders, policyholders (actual or prospective), or other creditors of the Bank’s regulatory actions and interventions (specific directions). It seems extraordinary to say that managers and directors of a company cannot tell their owners – the people they actually work for – about important developments affecting their (the owners’) company. It runs against most canons of what we understand about the importance of trust, or disclosure, and of the relationship between principals (owners) and agents (managers and directors).

I also haven’t yet read the full report the Reserve Bank commissioned on its handling of the CBL affair (and remain sceptical that a report commissioned by Bank management – and which apparently sought no outside perspectives – was likely to be even close to a definitive assessment). But I did turn to the short chapter 15 (from p136) on “Confidentiality and Disclosure”.

In that section, the reviewers outline the relevant parts of the legislation that the Reserve Bank was using, and was constrained by. They refer first to Section 135 of the Insurance (Prudential Supervision) Act covers the protection of data supplied to the Reserve Bank for prudential purposes. This provision is not actually very relevant here: it is mainly designed to ensure that the Bank – and Bank staff – can’t, by accident or intent, treat confidential information lightly. And even then, the Bank itself can choose to release material in a number of circumstances, including these two

(c) the publication or disclosure of the information, data, document, or forecast is for the purposes of, or in connection with, the performance or exercise of any function or power conferred by this Act or any other enactment; or

(e) the publication or disclosure of the information, data, document, or forecast is to any person that the Bank is satisfied has a proper interest in receiving the information, data, document, or forecast; or

Section 136 also allows the Bank to approve publication. And so stories that suggest that the Reserve Bank was not free to publish information about its concerns or its actions, under pain of potential heavy fines, are just not correct. The reviewers themselves run this quite misleading line.

The confidentiality obligation on the Bank is an onerous one. Officers and employees of the Bank, and investigators, are liable on conviction to up to three months’ imprisonment and/or a fine up to $200,000 if they do not comply with this provision.

Rogue or cavalier employees are (rightly) at risk. The Bank itself has considerable protections and freedom of action (again, largely rightly so).

The reviewers then turn to the (much more relevant) provisions around the disclosure of the giving of directives. In July 2017, the Bank issued to CBL Insurance a direction covering a variety of matters, operating under section 143 of the Act. Section 150 of the Act makes it an offence for anyone to disclose (other than to directors and advisers of the directed entity) that a direction has been given. Again, there are substantial fines for breaches. But, again, this provision of the Act did not constrain the Reserve Bank, because the Bank itself is free to disclose the existence of the direction, or to allow others to disclose the fact of the direction.

The Bank itself has subsequently sometimes sought to imply that really the confidentiality of the directions was CBL’s choice, arguing (factually correctly) that when in February 2018 CBL requested that the confidentiality restriction be lifted, the Bank agreed. But that looks a lot like distraction. It is clear that, whatever the views of CBL managers and directors, in July 2017 the Reserve Bank was insistent on keeping the fact and content of the direction confidential. It acknowledged as much in a response to an OIA request from NBR in April 2018.

The Reserve Bank’s self-chosen reviewers (the one with some expertise in the field being a former Australian insurance regulator) backed the Reserve Bank’s call on this point.

It was appropriate to maintain confidentiality over these steps. Matters were at a fact-finding stage. The Bank had serious concerns that warranted action, but it had not yet gathered the relevant information, tested it with CBL, and arrived at a sufficiently informed position. Obviously public disclosure of the fact of an investigation or initial concerns that have not yet been tested would be highly damaging to the reputation of CBL and to the value of its parent.

Except that by this time matters don’t seem to have been just at the fact-finding stage. Rather, the direction imposed specific restrictions on CBL Insurance’s business – the sort of action the Reserve Bank never engages in lightly (and, as the rest of the report apparently elaborates, coming after several years of concerns and fact-finding).

The reviewers go on to defend the Reserve Bank, arguing

The primary reason for confidentiality is that the Bank, quite correctly, is cautious about releasing information on any licensed insurer (or licensed bank) that may affect public confidence in the licensed company until the Bank is sure of its position. The confidentiality requirement, however, creates a quandary for the boards of listed companies who have a continuous disclosure obligations under NZX rules/Corporations Act 2001 (AU) rules.

In the CBL case, the position is also confounded to some extent by the fact that CBL Insurance is a subsidiary of the listed entity, CBL Corporation, which itself is not licensed.

Given the risks to public confidence in a licensed insurer if the Bank is carrying out an investigation or otherwise querying the credentials of an insurer before anything is proven, it is entirely appropriate for the Bank to maintain confidentiality by not making any public disclosures itself and also exerting control over any potential disclosures by the insurer.

Expressed another way, it is important that the Bank retain the power to intervene at any time in the affairs of an insurer. The Bank has to be able to recognise and choose to act early on any potential risk issue that it identifies and it also has to be able to stand back, without adversely affecting public confidence in the insurer, if the potential risk is not realised.

Before concluding

The Bank’s actions in relation to confidentiality and disclosure in 2017–2018 were appropriate.

We do not consider there was any earlier occasion when it would have been appropriate for the Bank to make public disclosures.

The lack of disclosure at the time of interim liquidation can be said to have been awkward for shareholders because, with no prior disclosure by the Bank or CBL, they were deprived of information that they may well have judged to be relevant to their position as investors. Arguably it was also awkward for policyholders, but that is a secondary matter in the eyes of investors.

On that point we note that CBL Corporation issued two relevant press releases in August 2017. In the first, on 18 August 2017, it disclosed concerns by the Gibraltar FSC over Elite’s claims reserves, the Gibraltar FSC’s reference to possible inadequacy of CBL’s claims reserves, and announced a reserve adjustment. The CBL Corporation share price reacted at the time, falling some 30%, but a week later there was a second press release that promoted the company’s prospects and gave a purported explanation for the claims reserving adjustment. The share price recovered by around 10% and then remained more or less static until suspension of trading in February 2018.

It is the policyholders, however, to whom the Bank owes its responsibility, not the investors. The Bank’s essential prudential concern always must be that policyholder promises can be honoured, irrespective of the fate or views or fortunes of shareholders.

I’m not entirely persuaded, on a number of counts. And I say that even though it is quite plausible that the way the Reserve Bank handled this specific aspect of the affair (non-disclosure) might have been in accord with common supervisory practice.

Here it is worth having a look at some of the specifics of the New Zealand act. For example, the purpose provisions in the legislation

When this legislation was being planned I argued that only the first strand should be included, and recall arguing explicitly that having “promote public confidence in the insurance sector” could, at some future date, be used to defend keeping real problems secret, in ways that might support short-term confidence, but would risk undermining long-term confidence in the sector and in the regulation/supervision of the sector. That seems like a valid concern. But even with that provision in the legislation, it provides no clear guidance on whether specific regulatory interventions should be kept secret, since the goal is not to protect individual firms, but with a sectoral focus. And if one believes in the efficacy of supervision – I tend to be sceptical – knowing that the regulator is (a) on the ball, and (b) not hiding stuff, is most likely to support a sound and efficient sector over time, and support public confidence in the bits of the sector where such confidence is warranted.

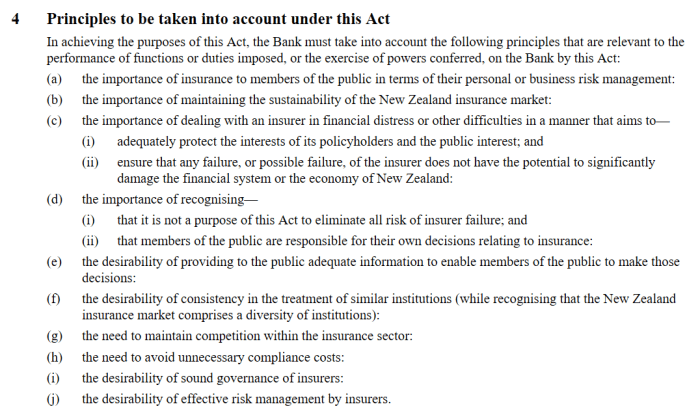

The Act next has a long laundry list of “principles” – no hierarchy, no weighting, no nothing (the sort of list Paul Tucker, in his book on delegated power, including to central banks, frowned on).

But they are still worth mentioning because, contrary to what the reviewers imply, the New Zealand framework is not exclusively built around policyholder protection; indeed, even the one bullet that explicitly mentions policyholders puts the “public interest” as of equal importance. As importantly, look down a couple of rows and you find another principle: “the desirability of providing to the public adequate information to enable members of the public to make those decisions” (ie regarding insurance), which might argue for as much transparency as possible. In short, you could pick any approach you like out of these purposes and principles (which makes it bad legislation from a citizen perspective – albeit beloved by officials), and none of these specific considerations are discussed by the reviewers in considering the disclosure/confidentiality issues around CBL. At least from the wider public perspective, that was a missed opportunity.

It is worth bearing in mind that as a society we have generally come to favour the continuous disclosure approach various stock exchanges have now adopted. Inside information is supposed to be kept to an absolute minimum, with owners being presumed to be entitled to know of any material developments affecting their companies. Shareholders provide the capital than underpins the provision of services and markets, including those in insurance. Continuous disclosure provisions typically have a carve-out where disclosure is prevented by law, and that is what the parent of CBL Insurance relied on in this case (that NBR OIA I linked to earlier has the text of email exchanges with CBL’s lawyers on non-disclosure to the market). In this case, there was no automatic protection for information about the Reserve Bank’s direction – which was highly relevant to shareholders, and others dealing with the company and its associates – since the Reserve Bank had full discretion to allow the fact of the direction to be disclosed (an option it explicitly rejected in an email dated 22 August 2018).

In this case, it may well have suited both the Reserve Bank and CBL managers/directors to keep the directions confidential, but their interests are not necessarily representative of either the public interest, or of the specific interests of the owners of CBL, or those dealing with the company. It isn’t even clear that their preferences aligned with the interests of policyholders, here or abroad: rather it is a paternalistic approach that says that the supervisor is better placed to look out for the interests of policyholders than are (actual or potential) policyholders themselves. The evidence for that proposition seems slim – including, in this particular case, based on what we read of the Bank’s handling of CBL over several years.

There are no easy or straightforward answers to these issues, which is why it would be valuable to have a fuller, and more open, exploration of the issues. In principle, I believe it would be better – including reducing the risk of the supervisory being morally liable for any later losses in a failure event – for the default presumption to be that any use of formal direction (or similar) powers by a prudential regulator should be disclosed by that regulator, and should be subject to usual continuous disclosure provisions in the case of listed entities. The alternative both corrodes public trust in regulatory agencies – what are they up to that we don’t know about? – and corrodes the trust that needs to exist, and be robustly nurtured, between managers/directors and owners and creditors of private business entities

But there are risks to adopting this approach. The ones I’m concerned about – at least in the insurance sector – aren’t some sort of market panic (runs on insurance companies don’t have the meaning they do for banks). The share price of a listed entity might fall sharply – but that seems an appropriate possibility – and people might become more reluctant to deal with the firm (ditto, at least until after hard questions have been adequately answered). My concern is more that disclosure might make the supervisory entity more reluctant to act when it should, and more reliant on moving into the non-legal shadows, relying on pressure and threats of direction. Perhaps too we would risk seeing courts more actively involved as the regulated entity sought injunctions to stop a supervisor using directive powers? Those are real risks that need debating, but they should not be conclusive arguments, especially when the alternative involves the regulator and managers/directors getting together to keep highly valuable information from shareholders (whose money is mostly at stake), policyholders, prospective policyholders, and other creditors.

My interests are really less on the specific CBL case – although specific cases help focus attention – than on thinking about potential problems with banks at some future date. There are very similar powers in the Reserve Bank Act re the confidentiality of directions to banks, and the issues get even more complicated because (a) bank runs are a real issue, (b) our bank supervision legislation does not have a depositor protection focus, (c) the disclosure regime has been designed to encourage creditors to take responsibility for themselves, (d) the proposed deposit insurance regime is very limited in scale, and (e) most of our banks are subsidiaries of foreign listed entities (can the Reserve Bank enforce directions on Australian parents?). My own prior is that the world’s banking regulators do not have such a stellar record that we should be entrusting them with such powers of coerced silence, preventing companies telling their shareholders and creditors etc that they are subject to directions from the regulatory authority. Perhaps the best thing might be more directions, made public at the time they are given as a matter of routine, so that markets, media, and the public can learn to weigh and evaluate the significance or otherwise of the issues and risks the regulator is highlighting.

I’m sure mine is a minority position, and I’m putting the issue out there as much as anything to try to encourage some reflection and debate on the issues. In reality, perhaps the issues are not be black and white (in general – although each specific involves final decisions), but regulators need to demonstrate that they have earned the trust, and extensive powers, reposed in them. And our laws, and the applications of them, should be framed against principles of open government, accountability for regulatory agencies, and a belief that – within government and within firms – sunlight is typically the best disinfectant.

On which note, it is now the school holidays and we are heading off to find some sunshine and warmth. Most likely there won’t be another post here until 23 July.

PUBLISH – to Publish – legal definition of publication

Publication is the act of offering something for the general public to inspect or scrutinize. It means to convey knowledge or give notice. In Copyright law, publication is making a book or other written material available to anyone interested by distributing or offering it for sale.

https://legal-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/publication

Publish does not cover a private communication with the board

Disclosure – We are (were) covered by a LBP builders guarantee insured by CBL

LikeLike

RBNZ actions on AMP noticed by Michael West

AMP shares plunge

LikeLike

The RBNZ together with the FMA and the Police did issue a Countries High Risk Assessment Guideline for AML/CFT which they have made every dog and cat in NZ responsible for. Guess they have to act if the name Bermuda pops up as the Country of Origin of the acquiring entity. Smacks of a hive of AML/CFT activities.

LikeLike