The lawlessness of the Board of the Reserve Bank of New Zealand never ceases to amaze me, Just in recent years, there was clear evidence that the Board simply ignores the requirements of the Public Records Act. There was their facilitation of what was almost certainly an unlawful appointment of an “acting Governor” in the run up to the election (decent outcome in the abstract, but unlawful nonetheless). And, of course, they play fast and loose with the Official Information Act, apparently confident that the Ombudsman is largely toothless. It is all the more extraordinary in that since 2013 the Bank’s Board has had a senior lawyer as a member. I’d not paid much attention to him, not knowing anything about him, but when I finally met him last week – where he told us he “trains judges” – it reignited my interest in just how a senior lawyer makes himself party to so much questionable – borderline at least – conduct by a public agency.

We’ve seen a repeat of this sort of “the law doesn’t really apply to us” mentality around the release of papers relating to the appointment of the new statutory Monetary Policy Committee. I wrote about that here. I’d lodged requests with both the Minister of Finance and the Bank’s Board. The Minister took a while to respond, but his responses were within timeframes allowed by law (a single extension of time, if that extension takes the deadline beyond the usual statutory 20 days). The Board, on the other hand, extended, extended, and extended again – quite unlawfully (Ombudsman advice makes that interpretation quite clear) – before finally releasing some material a couple of weeks ago. They did have a fairly junior person apologise for the delay, but that is pretty meaningless (no penalty on them – even after I complained to the Ombudsman – and no sense of any serious intention to amend their ways). And yet these people – the Board – are supposed to keep the Governor in check (and the government is now proposing to give them even more formal powers).

But this post is mostly about the substance of the MPC appointments. There are two releases. The Board’s response is here, and the Minister of Finance’s release is here.

Grant Robertson OIA release on MPC appointments

I know for a fact that neither release is comprehensive (including things I’ve been told privately, things alluded to in what has been released, and rather obvious omissions – are we really supposed to believe that, eg, the Board chair did not brief the Board on his discussions with the Minister?) but what has been released does quite a lot to flesh out a picture of a process that doesn’t really seem to put anyone involved in a particularly good light. There are even signs that the Board is taking the Public Records Act a bit more seriously than they did around the appointment of the Governor. My earlier post on the new MPC is here: these releases answer some of the issues I raised there, mostly leaving me more concerned than I was previously.

One of my longstanding concerns about the new regime would be that it would largely replicate the dominance the Governor had in the old legislative model (where the Governor was, by law, the single decisionmaker). Part of the reason for that concern was the statutory majority of internal members of the MPC. All those internal members owe their day jobs to the Governor, who also decides on internal resource allocations, pay etc. A really strong Governor might encourage diversity of perspective and challenge. There has never been any suggestion Adrian Orr is that sort of person, indeed rather the contrary. And the external members are appointed on the Board’s recommendation, but…..the Governor himself is a member of the Board. And instead of distancing himself from the process, and leaving recommendations to the non-executive directors, the Governor was one of the three man interview panel for the external MPC nominees. Throw in the code of conduct the Board (Governor a member again) devised and clearly no one remotely awkward was going to get through the screening process. (Consistent with that, in the four months since the MPC took office, not one of the externals has said a word – that might, in part, be because no media have asked them questions, but there is nothing to stop a more proactive approach.)

Consistent with all this, the Board released the set of questions they used for their interviews with potential MPC appointments. There wasn’t much sign, from the questions, that the Board was looking for excellence (in anything), but there was certainly nothing in those questions to suggest they were looking for MPC members who robustly challenge, and offer markedly different perspectives over time to, the Governor and staff.

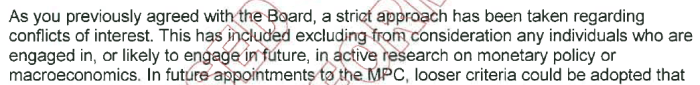

But it was much worse than that. This is from a Treasury note to the Minister, released by the Minister (note that the Board itself kept this secret)

This is simply staggering, or should be in a country with good quality competent institutions. And I know Treasury isn’t misinterpreting things, because I was told about this restriction some time ago by a person who was rejected on exactly these grounds – that they might be interested and knowledgeable enough about monetary policy to be doing some research on it. By this standard, I guess the Board and Minister (presumably aided and abetted by the Governor) would disqualify (a New Zealand) Ben Bernanke, Janet Yellen or (right now) John Williams, the head of the New York Fed and someone who – while serving on the FOMC – has continued to undertake research on monetary policy. I realise that expertise is going out of the fashion at the ECB (Makhlouf, Lagarde) but their new Chief Economist – former Irish Governor – Philip Lane has been an active researcher and writer. Or one could think of Andrew Haldane at the Bank of England, or….or….or. Is it now considered a negative – perhaps a disqualifying consideration – if the Reserve Bank’s chief economist was doing research on monetary policy, or does the disqualification only apply to externals, over whom the Governor has less control? It almost beggars belief that the Minister and Board would get together and disqualify anyone with specific serious expertise in monetary policy from a new Monetary Policy Committee. Sceptical as I was of the new committee in principle, even I was stunned when I learned of this prohibition.

(And, to be clear, I am not one of those who thinks an MPC should be stacked full of research macroeconomists – I’d be happy to have a couple of people, of the sort who ask hard questions and have good judgement, with little or no formal economics background at all – just that such people shouldn’t be ruled out in advance. As it is, the current MPC looks odd in that among its seven members there is not a single one who could really be considered to have a long record of depth of expertise in monetary policy and the New Zealand economy.)

So if the Board, the Governor, and the Minister weren’t looking for in-depth expertise, and weren’t looking for anyone to rock the boat, what were they looking for? The short answer – suffusing both sets of releases – is women. In none of the material released to me is there is any discussion about the sorts of expertise that might be sought, or how to build a committee with complementary sets of skills, but there is a great deal of unease – particularly channelled from the Minister’s office – about getting women selected (even to point, in some places, where there seemed to be attempts to strongly encourage the Governor to select a woman as his chief economist). There are records of early approaches by the Board Secretary to get possible women (and Maori) candidates (and a Treasury response which points out that there really aren’t that many adequately qualified women – not that surprising given how many women did (say) economics honours or masters programmes in New Zealand 30 years ago (in my own honours course at Victoria, the number was either one or zero out of about 15)). As it is, despite all the huffing and puffing, they ended up with only one women on the shortlist.

There were a couple of other things that were striking. The Board’s release records various email mentions of trying to identify candidates with legal backgrounds. This is almost a complete mystery to me, as the MPC has no regulatory responsibilities and the legislation it operates under is pretty straightforward (and the Bank has internal and external legal advisers if things do require any clarification). The MPC is about cyclical macroeconomics management, and communications thereon. Someone of a particularly suspicious cast of mind might suggest that a legally-qualified MPC member would be one less knowledgeable person for the Governor to have to bother about. I’m just genuinely puzzled.

The Board’s release also recorded various exchanges among senior Bank managers about what sort of person might be suitable as an external MPC appointee (they were looking for names to suggest to the Board). What took me by surprise was the aversion to overseas appointees. As regular readers know, I do not think we should have (say) a foreign Secretary to the Treasury (or a foreign Chief Justice, or a foreign Governor) but I was always among those at the Bank who saw one of the advantages of moving to a statutory MPC is that it could allow the appointment of one foreign person, bringing a slightly different expertise and perspective to New Zealand monetary policymaking. It was never clear how feasible this would be – distance, and relatively low New Zealand salaries being an obstacle – but it has been tried, and appeared to work, in some other countries.

But that clearly wasn’t the view of the senior management last year. The then Chief Economist, John McDermott (for example) is quoted as saying

“overseas members would be a logistical nightmare and what is their interest in looking after New Zealand welfare and monitoring the NZ business cycle on a continuous basis? So no from me.”

There is no sign of any of his colleagues or bosses dissenting and no reference to possible overseas appointees later in the any of the documents. As it is, it isn’t clear how much “continuous monitoring” of the New Zealand economy the MPC members are actually doing (a recent conversation I was party to suggests not much in at least some cases).

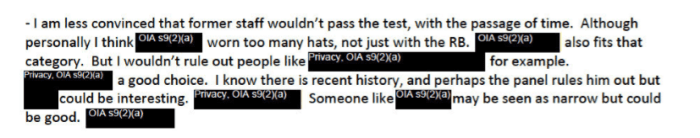

Management also debated the issue of whether former RB staff or Board members should be considered (I suspect some might have liked to have Arthur Grimes appointed). The consensus seems to be (reasonably enough) that there needs to enough distance for such a person to be genuinely external. For groupies, one can try to guess which names are deleted in this paragraph

Disconcertingly, there are signs that management was open to have serving public servants appointed provided they didn’t currently work for agencies too close to things macro. There should be an absolute prohibition on anyone working for a government department or Crown entity (other than as an academic) being considered for a part-time external MPC appointment in an (operationally independent) central bank.

The final point I wanted to touch on answered one of my questions from a few months ago. Writing about the externals I noted

One area where I do have some concern is around the role of the Minister of Finance in these appointments. In principle, I think the Minister should be relatively free to appoint his or her own preferred candidates, and should be fully accountable for those choices (including through the sort of non-binding “confirmation hearings” – of the sort UK MPC members face – that I’ve proposed for New Zealand). As it is, on paper the Minister has no say at all (can reject Board nominees, but nothing more).

But then I’m a bit troubled by the way in which the Board – all but one appointed by the previous government – ended up delivering to the Minister for his rubber stamp a person who was formally a political adviser in Michael Cullen’s office when Cullen was Minister of Finance (Peter Harris) and another who appears to be right on with the government’s “wellbeing” programme. They look a lot like the sort of people that a left-wing Minister of Finance – one close to Michael Cullen – might have ended up appointing directly. I don’t think Peter Harris is grossly unqualifed for the role, but I am uneasy that one of the very first external appointees is a former political adviser to a former Minister of Finance of the same party as the one making the appointment. …. (I don’t think former political advisers should be perpetually disqualified, but it might be more confidence-enhancing had they been appointed by the other party from the one for which they used to work – thus Paul Dyer, former adviser in Bill English’s office, would probably be better qualified for the MPC roles than any of the recent external appointees.)

I’m left wondering what sort of behind-the-scenes dealings went on to secure these appointments. I hope the answer is none. I’d have no particular problem if, while the applications were open, the Minister had encouraged friends or allies to consider applying. I’d be much less comfortable if he had involvement beyond that, prior to actually receiving recommendations from the Board. It isn’t that I disapprove of politicians making appointments, but by law these particular appointment are not ones the Minister is supposed to be able to influence. So any backroom dealing is something it is then hard to hold him to account for.

The relevant provision of the Act says just this (buried in a schedule)

Appointment of internal and external members

The Minister must appoint the internal and external members on the recommendation of the Board.

It is very similar to the provision governing the appointment of the Governor. That provision has been sold consistently as a model under which the Board puts forward a name, and the Minister can either accept or reject the person, but cannot interpose his own nominee. If the Minister rejects the Board’s nominee, the Board has to go back and come up with another name. The provision was explicitly intended to leave almost no discretion to the Minister. (It isn’t a framework I approve of, but it is New Zealand law).

You will recall that in that earlier post I wondered quite how it was that the new MPC just happened to contained two obvious left-wing people, one a former political adviser in the office of a Labour Minister of Finance. The material released to me answers that question pretty clearly.

I’d assumed that the Board had put up three names to the Minister and he had either accepted them all, or perhaps (though unlikely) had vetoed one name and the Board had then come up with another. But that wasn’t what happened at all. Instead, the documents disclose that the Board put up seven names to the Minister for the three external appointeee positions, not ranking or prioritising them at all, and giving the Minister complete leeway to choose any three of the seven. Actually, they went further than that, in that the Board told the Minister that they had interviewed nine people, and listed the names of each of them, more or less inviting the Minister to suggest that if he didn’t like the seven names the Board recommended he could probably have one of the spare two (since it described all nine as “appointable”).

The documents also make clear that Caroline Saunders was the only woman on the shortlist (or certainly of the recommended seven). Since Saunders has no background in macroeconomics or expertise in monetary policy, and given that strong focus in the documents on getting women nominees, it is unfortunately hard to avoid the suggestion that she was a “diversity hire” – chosen for her sex rather than for the expertise she would bring to the MPC. In the circumstances, how could the Minister not have chosen her? One would hope it wasn’t so, but – and this is problem with quasi-quotas – it is impossible for us, or for her, to be confident that it wasn’t so. Perhaps over time she will fully justify her selection on the substance, but at present there is no data either way.

Perhaps specialist lawyers will have a different interpretation, but I struggle to see how offering the Minister a list of seven – or even nine – names and saying “choose any three” is the plain meaning and intention of the legislative text (would offering a list of 50 and saying “choose three” – if so, the provision is gutted of any meaning and protection?). The pool of potential MPC members really isn’t that deep in New Zealand and yet – despite the fact that the law puts the onus on the Board – we don’t even now know whether we have the best three external people on the MPC. If this approach is lawful, it must be borderline at best. (There was, for example, no sign of them adopting that approach to the internal MPC appointees – there the Minister was given a list of two names for two vacancies, the approach envisaged in the law.)

My own preferrred model remains (the more internationally common) one in which the Minister of Finance is free to appoint whomever he or she prefers to the MPC. I would complement that with non-binding confirmation hearings of the sort used in the UK. Under that model, responsibility for the appointment rests clearly with the Minister of Finance, and there is scope for proper parliamentary scrutiny before people take up a powerful role. Where this (brand new) legislation ended up is that the Minister can appoint his mates, within limits (but pretty broad limits) while pretending that the real choices were made by the Board.

In the end, after months – not at all consistent with the spirit of the OIA let alone the letter – we did get a fair bit (by no means complete) of information offering insight on the MPC selection and appointment process. Unfortunately that information tends to cast another shadow over the process, and suggests that the Board – whose members have no real expertise in relevant areas – continues to see its primary role as being to accommodate and humour the Governor and, now perhaps, to accommodate and humour the Minister, all behind closed doors.

And there is, of course, also the extraordinary secrecy as to how much these (possibly) second or third XI externals are being paid. So much for openness and transparency.