That was the title of Wellington economist Peter Fraser’s talk at Victoria University last Friday lunchtime on why Fonterra has failed (it is apparently also a term in use in various bits of popular culture, all of which had passed me by until a few moments ago – and a Google search). Peter is a former public servant – we did some work together, the last time Fonterra risks were in focus, a decade ago – who now operates as a consultant to various participants in the dairy industry (not Fonterra). He has a great stock of one-liners, and listening to him reminds me of listening to Gareth Morgan when, whatever value one got from purchasing his firm’s economic forecasts, the bonus was the entertainment value of his presentation. The style perhaps won’t appeal to everyone, but the substance of his talk poses some very serious questions and challenges.

The bulk of Peter’s diagnosis has already appeared in the mainstream media, in a substantial Herald op-ed a few weeks ago and then in a Stuff article yesterday. And Peter was kind enough to send me a copy of his presentation, with permission to quote from it.

His starting point is with the misplaced belief among senior political figures 20 years ago that by allowing the creation of Fonterra – using legislation to override the Commerce Commission – the door would be opened to the evolution – in pretty short order – of something equivalent to New Zealand’s Nokia. In revenue terms, the promise had been

From a starting point of only $5B, they outlined a six-fold increase in revenues in only 10 years to $30B.

Critically, just under two-thirds of the $30B would come from what is euphemistically known as ‘value add’: specialised ingredients and biotech-heavy products.

So this was almost $20B of revenue from a starting point of ‘nothing’.

Actual revenue now, 17/18 years on, is about $20 billion (including a structural improvement in world dairy prices) and relatively little is from those vaunted specialised products. The rate of return on that business, in turn, is barely higher than that on the bulk commodity business.

And

A much cited figure is the 2018 value report published by the International Farm Comparison Network (IFCN). This ranked Fonterra 17th out of the 20 companies in terms of value creation.

Its figures show while Fonterra collects the second largest amount of milk (and is the world’s largest milk exporter), its estimated turnover per kg of milk solids is only US60c.

By comparison, Danone is the 11th largest milk processor, but it turns over US$2.40 for every kg to make it the best performer. Nestlé is next at US$1.90 per kg. The average across the entire group is $1.00.

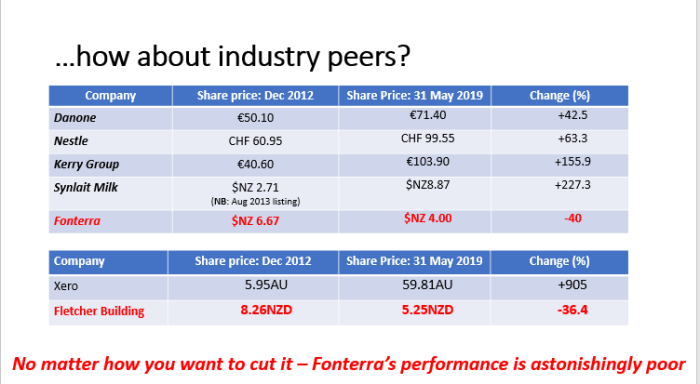

The “failure” is nicely illustrated in the share price (the non-voting shares were listed in 2012). The comparison against the NZX index is stark, as is that against industry peers.

Apparently the share price fell further in June (and Peter told us that on Thursday the share price closed a touch below the initial valuation back in 2002).

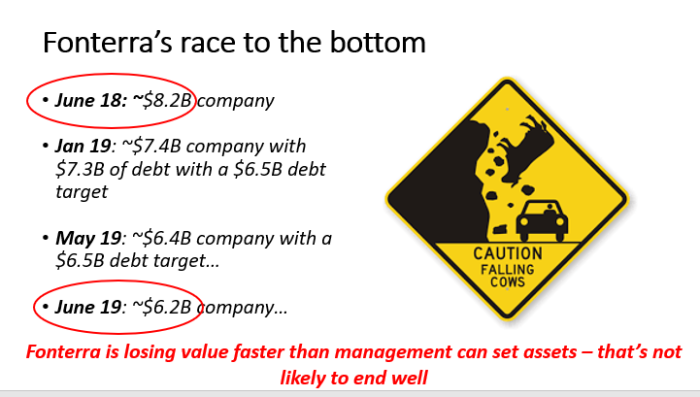

Fonterra asset sales have been in focus this year. They started when the market value of the company was much higher than it now is, and haven’t kept up, so that the ratio of market value to debt is now higher than it was.

For various reasons I don’t want to get into the fine details of DIRA, but as I understand the essence of Peter’s story is that:

- farmers themselves never much cared about the added-value ideas (New Zealand’s Nokia and other dreams). Why would they? They are farmers, and their interests were primarily about a high price for their milk, and a high/rising price for their land.

- between provisions in the legislation and in the constitution of Fonterra, the rules mean Fonterra has been paying materially too much (Peter says 50c per kg) for milk purchased from suppliers,

- dividends on the shares have been limited, which doesn’t matter to (voting) farmer shareholders, but does matter to the outside shareholders, and retentions (or retaining earnings) – now the main source of additional capital in a cooperative – have also been low.

- given Fonterra’s dominant market position, the too-high milk price also drives up the price of milk other industry participants have to pay. That has encouraged more milk production – including “half way up Mt Cook”, and with associated environmental issues – but also makes it difficult for firms to make profitable investments in other (value-added) products.

Peter again

…the idea of using the ingredients business as a springboard to a value creation business was part of the original concept and is actually a good one.

The problem is, it basically didn’t happen. There are two reasons for this.

Firstly, Fonterra relies heavily on payout subordination so has very high gearing – something it seems the Board has failed to learn from after courting near disaster during the GFC.

This constrains Fonterra’s ability to borrow further, such as for acquisitions or to finance value creation activities.

The other problem is woeful levels of retentions, which are critical for a coop because without new capital from a growing milk supply, retentions are only other way of getting new capital.

So Fonterra remained a capital starved, deeply indebted and under performing farmer-owned cooperative.

That “near-disaster” ten years ago (his account here) was when I first met Peter. Global funding markets was seizing up, world dairy prices had fallen sharply, land prices were falling, and lenders to dairy farmers were becoming seriously uneasy (including parents in Australia that hadn’t fully appreciated quite how much exposure, to a sector with very illiquid collateral, had been taken on). In those days, struggling farmers had one buffer and Fonterra one exposure, that doesn’t exist today – redemption risk (on the farmers’ own production-related shares in the co-op).

That particular risk has now been shifted back onto farmers, which probably leaves Fonterra’s own lenders a bit more comfortable (but in turn removed one discipline from the Board). But there is still a hugely high level of debt (presumably largely from international markets and banks).

Peter argues that, unless something dramatic changes pretty soon, Fonterra is likely to run into crisis within the next five years or so (and, he argues, since the current government probably likes to believe it will still be in office five years hence, they really need to focus on this now).

I was among those at the presentation the other day who weren’t entirely sure how this mooted crisis would come about, or what form it might take. After all, Fonterra isn’t a conventional company. The traded shares – the price of which has been falling away – are not a direct stake in Fonterra. The share price could go to zero (if, say, unit holders lost confidence there would ever be dividends, tied to value-added returns) without rendering the co-op itself insolvent. The banks and bond markets that have lent to Fonterra are exceedingly unlikely to lose their money – that is what (milk) payout subordination means – but it is likely that quite a few of the existing facilities have caveats and covenants about financial conditions Fonterra has to meet. And the asset sales programme of recent months seems fairly explicitly premised on the idea that the market price of the shares (and those the notional market value of the co-op) mattersa, including to lenders. Presumably there has to be a risk that if Fonterra’s underperformance continues, lenders would become increasingly reluctant to renew existing facilities, and the costs of what credit they could still obtain would rise?

And, of course, there is only so much money to go around (perhaps rather less if commodity prices were to fall away sharply in a recession in the next few years), and what is paid to providers of capital (debt or equity) can’t be paid to farmers. The dairy farm industry has an uncomfortably high, and rather concentrated, level of debt already. And dairy land values are underpinned, to a considerable extent, by the actual and expected milk price. 50 cents off the milk price for one year might not make much difference to land values, but if Fraser is right and prices are perhaps 50c too high generally, adjusting the milk price itself into line with that would severely impede the profitably of many dairy farms (as Fraser notes, on-farm costs have been rising, and much of any margin New Zealand dairy farmers had relative to the rest of the world appears to have been greatly eroded. Fonterra also risks losing suppliers, and ending up with stranded assets.

The sketch outline of Peter Fraser’s story – directional pressures – seems plausible to me, but here I’m mostly trying to tell his story rather than sign up to it all. I don’t claim enough industry familiarity for that, and haven’t been exposed to serious alternative arguments – if there are some, bearing in mind the repeated underperformance over a long time now. The Fonterra statement to Stuff, in response to Fraser, didn’t instill great confidence

Fonterra managing director co-operative affairs Mike Cronin responded in a statement:

“Our focus right now is on the future of our co-op. We’re well down the path of a strategy review which will enable us to deliver on our potential and meet people’s expectations. We know where we want to go, but how we get there will take time. We will play to our strengths – our New Zealand provenance, our pasture-based farming model and our dairy know-how.”

Fraser’s presentation ended with these lines

That final line – Westland as dress rehearsal – is also where I want to end. Fraser argues that, most likely, Fonterra will need extensive recapitalisation and that – short of nationalisation – there is no likelihood that the New Zealand market could provide the necessary capital, and thus that a foreign takeover is the most likely market solution.

Perhaps it would be the eventual market solution, but I struggle to believe that the market would be allowed to operate in such a case. The politics of foreign ownership of Fonterra would be too much for any major political party – in today’s climate – to swallow. Most likely, we’d have government moneypots – the New Zealand Superannuation Fund and ACC – corralled to provide the new capital (those two are already half owners of KiwiBank, and NZSF falls over itself to pursue politically-attuned projects).

If I read Peter correctly, he believes things could be turned around. But that there is little sign of it from either Fonterra – and no demand for it from their farmers – or from the government.