I suggested last week that I might devote a post to picking through the arguments that the New Zealand Initiative’s Bryce Wilkinson and the Social Credit group have been making – including in attacks on each other – about fiscal policy, monetary financing etc. Even with another round of full-page adverts from Social Credit in the weekend papers, I’ve decided to set that to one side for now. I guess my bottom line is that I think Social Credit is quite wrong in the longer-term. I disagree with them less about the near-term, in fact there (as I put it in my previous post) I think they are insufficiently ambitious. Anyone interested can read that previous post (I had a polite and engaging email from the leader of Social Credit who thought the post was “most even handed”, even though he disagreed with my bottom lines).

Instead, I want to work through a post on how one might best respond to a really sharp and substantial economic contraction – partly government-induced, but increasingly just a response to seriously adverse exogenous events. In this case, of course, the issue is, the global pandemic, the effects of which seem likely to be with us for some time (quite possibly at least several years).

Before doing so, while there will be lots about governments and central banks here, it is worth remembering that economies (firms, households etc) can and would adjust themselves anyway. But there is a fairly strong consensus that macroeconomic policies, done reasonably well, can asssist in getting the economy back to full employment faster (perhaps quite a bit faster, but we don’t know the counterfactuals with any certainty) than by simply leaving people to sort things out themselves. That won’t always be the case – there is a reasonable case that governments made things worse for quite a bit of the Great Depression – but I’m happy to take it as a starting presumption. And whether or not you or I agree, government agencies are going to do stuff anyway. This is an attempt to contribute to debate about what they should do. My worry, to put my cards on the table, is that they won’t do enough, and that what is done will be quite misfocused.

In a really severe downturn we typically look to some mix of monetary policy and fiscal policy to help out. In the case of fiscal policy, the default is mostly about being helpful by sharing the losses. In effect, our tax system makes the government something like an equity partner in all economic activities: when times are good government revenues rise strongly and when times are bad revenue falls away a lot. Typically, we look to governments to position themselves to ride through most of the cyclical fluctations, such that debt ratios fall (somewhat) in good times and rise (somewhat) in bad times. That is what is known as “letting the automatic stabilisers work”. The biggest effects are on the revenue side, but there is some expenditure impact as well: more unemployed people means more spending on unemployment benefits.

On the monetary policy side, central banks have to actually act to be helpful. That is because our system works through central banks setting a short-term policy rate (here the OCR) at a level economic conditions (including inflation) call for. When circumstances change, only the central bank can change that policy rate. Longer-term rates are, of course, free to move, but they are influenced not just be savings and investment preferences – the core fundamentals that drive where interest rates should be – but by what people think central banks will do.

For really big adverse shocks, those fiscal effects (the “automatic stabilisers”) aren’t small. Suppose that GDP for the year to March 2021 were to be 15 per cent less than normal – not a forecast, but not a wildly implausible number either. If there was a balanced budget at the start of the period, it would be easy to envisage a deficit of 5-6 per cent of GDP, just by doing nothing. That would, typically, be regarded as a “good” deficit – the sort any well-managed government should certainly be willing to run in such circumstances.

Then again, think about the – quite serious – recession we had in 2008/09. The level of GDP fell then by about 3 per cent. Underlying trend growth might have been about 2 per cent per annum, so a gap of about 5 per cent of GDP (similar to the peak output gap estimates for that period). Automatic stabilisers might then be worth only 1-2 per cent of GDP.

By contrast, the OCR was cut by 575 basis points during that period. Short-term retail rates fell by less than that, and inflation expectations also fell during the period, but there were significant reductions in real retail interest rates. In addition, the exchange rate fell, by 25 per cent or more. As was typical in floating exchange rate countries – ie ones that could set their own monetary policy – the bulk of the adjustment burden was put on monetary policy.

In quite a few countries there were also quite big discretionary fiscal stimulus packages as well, on top of the automatic stabilisers. Nothing of that sort was done in New Zealand after the recession became apparent, However, as it happens, the Labour government (in office until November 2008) had put in place a fairly stimulatory fiscal policy anyway, when they (and their Treasury advisers) assumed times would stay good. On OECD metrics – cyclically-adjusted and underlying balance estimates – those measures generated a fiscal impulse equivalent to 4 per cent of GDP (the change in the structural balance from the position in 2007 to that in 2009). It was a larger stimulatory effect than seen in some countries that launched crisis discretionary stimulus packages. If it hadn’t been for that fiscal stimulus that happened to be in place anyway, the case for even deeper OCR cuts would have been strong.

In combination these were really quite large effects:

- 575 basis points of OCR cuts,

- a 25 per cent fall in the exchange rate,

- a four per cent of GDP fiscal impulse

as well as all sorts of guarantees and liquidity measures to limit the extent to which monetary conditions tightened.

And yet it is worth remembering that it was 10 years before New Zealand’s unemployment rate got back to about the sort of rate many economists – and the Reserve Bank I think – would think of as the normal level (or NAIRU) given labour market restrictions etc. It took seven years for the employment rate – which has been trending up over time – to get back to pre-recession level.

And that was even with the fair winds of a robust terms of trade and a big boost to demand from the Canterbury repair and rebuild project. And from a starting point in 2007 in which there was not that much cyclically wrong with the New Zealand economy.

What about our previous really severe recession – worse in almost every regard for us than 2008/09 – at the end of the 1980s and early 1990s? Of course, there was lots else going on – lots of reforms and structural change that were shaking loose from the labour market, and a mania that had huge amounts of very bad lending, and misallocation of investment resources, in the run up. In addition, policy was still trying to drive inflation down. And, of course, there were structural tightenings going on in fiscal policy – although by this time less than is often supposed (perhaps a couple of percentage points of GDP, on OECD numbers). The unemployment rate rose from about 4 per cent to about 11 per cent.

In response, and in real terms, the short-term interest rate fell by probably 700 basis points (over several years). The exchange rate fell by 20 per cent. But even then it took years to get us back to something akin to full employment.

So typically with very nasty recessions we see very big macro policy responses, sometimes passive (those automatic stabilisers, which are weaker in New Zealand than in many OECD countries).

Monetary policy typically does the bulk of the work. There is good reason for that:

- official interest rates can be adjusted very quickly (basically instantaneously) and – as it happens – can be unwound quickly too,

- interest rate “get in all the cracks” – affect people and firms across the economy,

- at a time when the economy has got poorer (even if just for a time), interest rate cuts spread losses, taking income away from existing savers and redistributing it back to existing borrowers (at least those among both classes who have voluntarily contracted to live with the risk of variable interest rates).

- lower interest rates tend to draw spending forward in time (to the period now where there is excess capacity and a shortfall in demand) – not just, or even primarily, by encouraging new borrowing from banks, but simply by prompting people to think that the reasons to put off spending aren’t as strong as previously,

- particularly for a country like New Zealand (it is different in the US, or countries with big positive NIIP positions like Switzerland or Japan) lower interest rates also tend to lower the exchange, encouraging New Zealanders (at the margin) to consume locally, increasing returns to those selling abroad, and attracting some demand from abroad towards New Zealand producers rather than foreign ones.

In fact, big reductions in (real) interest rates are what would happen in a market economy if a central bank were not setting a policy rate. In the end, what interest rates do in an economy is to reconcile savings preferences and investment intentions. In severe downturns, all else equal, investment intentions at any given interest rate plummet (whether by firms or households), and private savings preferences (firms or households) also tend to increase at any given interest rate. The reconcilation of those two forces is that the equilibrium interest rate – including the one consistent with promoting a speedy return to full employment – will fall, quite a lot. Broadly speaking, the job of the central bank is to follow those changes, and get market rates into line (that might involve specific liquidity interventions in quasi-crisis conditions, but it will certainly involve OCR adjustments).

And the beauty of relying – as countries were typically doing previously – on interest rates and monetary policy is that no one is compelled to do anything. If you didn’t want to be exposed to interest rate risk, you’d have taken a fixed-rate contract. If you didn’t want near-term exchange rate exposure, you’d hedge as much as you could. And if the interest rates fell sharply and you didn’t want to change your behaviour in response, you didn’t have to. Those with the most flexibility, those with the best opportunities, did the adjustment. It might be unsatisfying to politicians – no big announceables, no specific identifiable spender – but there is nonetheless a pervasive stabilising and supportive effect.

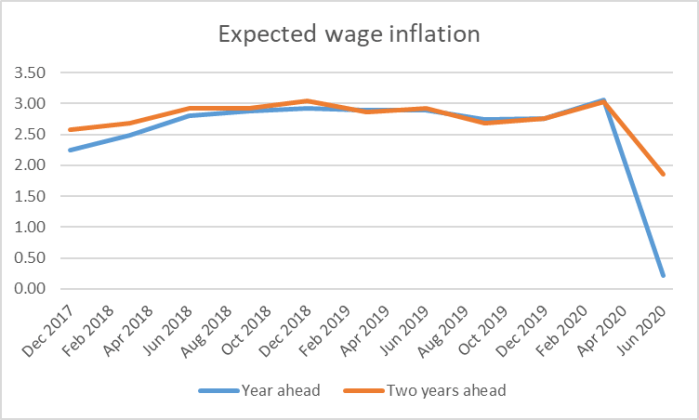

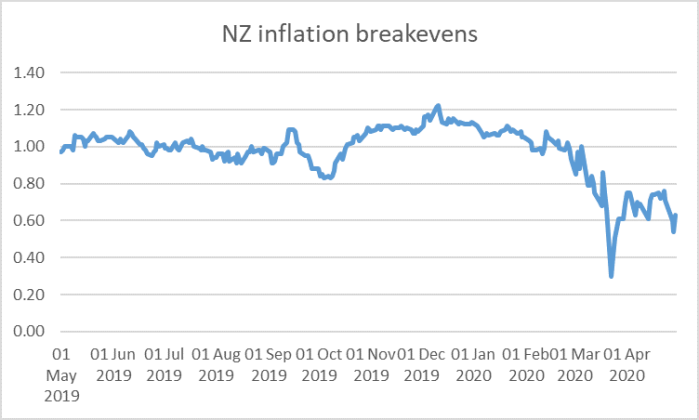

But this isn’t at all what is going on in the present savage recession – the one that, even as the most severe of the regulatory restrictions is lifted, is likely to see us left with a recession, and excess capacity in the economy, as severe as anything we’ve seen for a very long time almost nothing is happening with monetary policy. Real interest rates have barely moved: that’s true whether one looks as short-rates and adjusts for the fall in surveyed inflation expectations, or looks at the yields on the range of inflation-indexed bonds the government has on issue (where yields are no lower now than they were late last year). Oh, and the exchange rate hasn’t fallen by much at all either.

Sure, there has been plenty of activity to support liquidity in financial market. That has stopped conditions tightening, but done nothing material to ease conditions.

Instead, all the talk is of fiscal policy.

The automatic stabilisers will be at work, and although we haven’t yet seen much of that effect in the numbers it will be real in time. Plausibly, the automatic stabilisers alone could yet add 15 percentage points to the ratio of public debt to GDP over the next few years.

But the talk isn’t really of those pre-set conditions, but off the discretationary measures already announced with the prospect of more to come (perhaps including in Thursday’s Budget).

We’ve seen big dollops of money already, notably the $10 billion of so (just over 3 per cent of pre-crisis GDP) for the wage subsidy programme paid out already. Amid the numerous other big numbers tossed around, it isn’t clear how much else has actually been paid out (let alone how much of that will represent net fiscal costs over time). There have been additional real resources committed to the health sector, but in the macro scheme of things those effects are likely to be fairly small.

Probably no one really begrudges spending of that sort over recent weeks (even if there might be reasonable debate over some of the parameters of the wage subsidy scheme), but big as the numbers are, they also aren’t really the issue now: the money has already been spent, and probably even held up (to some extent) actual spending (on the little that was permissible) during the “Level 4” and “Level 3” periods.

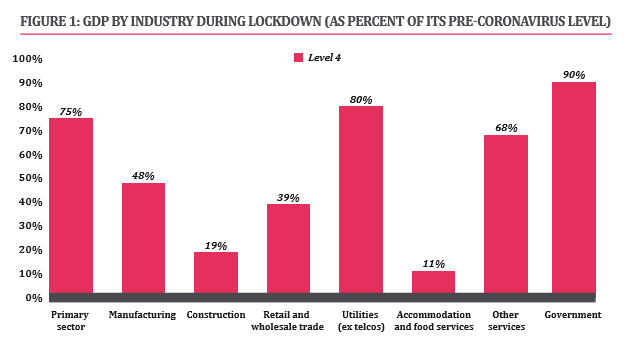

But that issue is where to from here, as we head out of the worst of the restrictions into an environment where even later this year GDP might still be 15 per cent below normal – stop and ponder that gap; it is too easy to get too used to really big numbers. An environment where the world economy is in deep recession, where the virus and uncertainty about it still stalks the earth (and even affects directly New Zealanders, who can’t safely assume there will be no return of the virus or restrictions) and where there is little prospect of our borders being very open at all. It isn’t as if it looks likely that we can simply count on animal spirits or even just the rest of the world to lift demand quickly in a way that would promptly get us back close to full employment.

Almost certainly, a prompt return to full employment will take a great deal more policy stimulus. But there is little sign it is likely.

The Reserve Bank is clearly reluctant to cut the OCR further, and has actually pledged not to do so before March. They talk (a lot) about their bond purchase programme being in some sense equivalent to substantial OCR cuts, but frankly that is just unsubstantiated nonsense (when neither the exchange rate nor real interest rates – anywhere along the curve – have fallen much if at all, all they’ve done is limit any unintended tightening). What scarces me is that people who count – notably the Cabinet, and the Minister of Finance in particular – may believe them.

And there seem to be a growing number of signals suggesting not that much can be expected from fiscal policy – whether comments from the Minister of Finance and the Prime Minister or, for example, the thoughtful column on the Herald website by Pattrick Smellie (once upon a time press secretary to Roger Douglas as Minister of Finance). I’m sure there will be baubles thrown around, old programmes repackaged, and some genuine stimulus proposals (some of which may never actually begin before the economy is pretty close to fully-employed anyway, even if that takes years). But this is a huge recession, it isn’t going away quickly, and for now the Minister of Finance seems content to have the Reserve Bank do nothing. It is a recipe for economic activity lingering unnecessarily below capacity for years, for unemployment lingering high for years – permanently scarring the lives of many of those affected.

At one extreme of the current debate there people who reckon going big on fiscal policy is something closely akin to a “free lunch” (Social Credit may actually believe it, but others come close). That almost certainly is not true.

If, perchance, monetary policy does nothing and stimulatory fiscal policy could speed up the recovery somewhat, then there is a modicum of truth in the “free lunch” concept – at least some resources which would never otherwise have been used will have been employed and productive. Even then, of course, the people who gain and the people who pay will be two different groups.

Ah, but some say, the additional debt just never needs to be repaid. And it is certainly true that (a) a well-governed market economy with a flexible exchange rate can run reasonably high levels of public debt, and (b) with very low long-term interest rates there may be a reasonable argument that the sustainable level of public debt (share of GDP) is higher than it was. It is also true that in a growing economy, so long as the budget gets back to balance (even if it takes five years from now), the debt to GDP ratio will gradually erode (with 2.5 per cent nominal GDP growth, the debt ratio would halve in 30 years).

(Oh, and ideas about the Reserve Bank somehow “writing off” the government debt it holds also change nothing – there would be just an intra-government book-keeping entry.)

But even having made all those points, there is still an opportunity cost to consider. Suppose that it really was now prudent to aim for a public debt to GDP ratio of 60 per cent, rather than something like 20 per cent hitherto. That gives government some additional deficit capacity for some years – getting to the new higher level – but surely we should want that capacity used for the highest returning projects. To some, that might (for example) be lower taxes on business income. To others, it might be better quality schools, or investment in public R&D, or even just higher benefit levels for those genuinely unable to provide for themselves (views will differ). Simply throwing money willy-nilly now at things that might help return to full employment quickly will preclude those options being exercised.

That is especially so when the monetary policy option is on the table. If the Governor and the MPC refuse to use it aggressively, the Minister of Finance could simply insist. The law was written that way 30 years ago, and the provisions were reaffirmed when this government reviewed the monetary policy aspects of the Act just a couple of years ago. Or he could get a new Governor/MPC, since the incumbents clearly aren’t doing their jobs. Shocking? Perhaps, but so should persistent high unemployment be.

All that is especially so when there are a variety of reasons why using monetary policy aggressively now should be attractive:

- savings just aren’t very valuable to anyone else right now (what should drive the returns), when there is a strong desire to save, and little willingness to invest, and yet term depositors are still earning positive after-tax real interest rates on very low risk investment (as the economy goes backwards),

- the government finds it appropriate to lend to businesses at zero interest rates (via the IRD, to people who presumably can’t fund themselves elsewhere) and yet the typical retail interest rate for existing borrowers – most of whom will be highly creditworthy taken together – is still significantly positive,

- for all the reported angst about commercial rents – which mostly are fixed-term commitments – there seems to be little focus on lowering explicitly variable-rate interest rates (plenty of attention on deferring interest, even though – as above – the market would naturally lower those interest rates significantly),

- the biggest winners from avoiding using monetary policy are (a) the relatively older segments of the population (those with the largest term deposit base, directly or through managed funds), (b) while the opportunity cost of using up fiscal space now will fall most heavily on the relatively younger segments of the population, as does the burden of servicing the existing private debt at interest rates the Reserve Bank refuses to cut. Not to be too delicate about these things, the older segements of the population were/are most at risk from the virus,

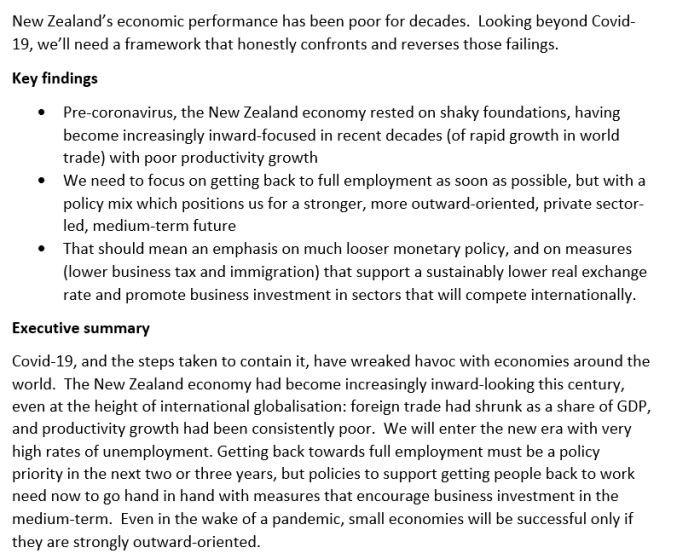

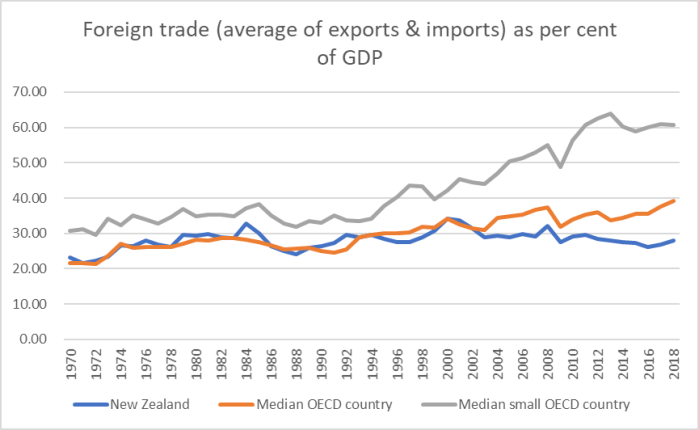

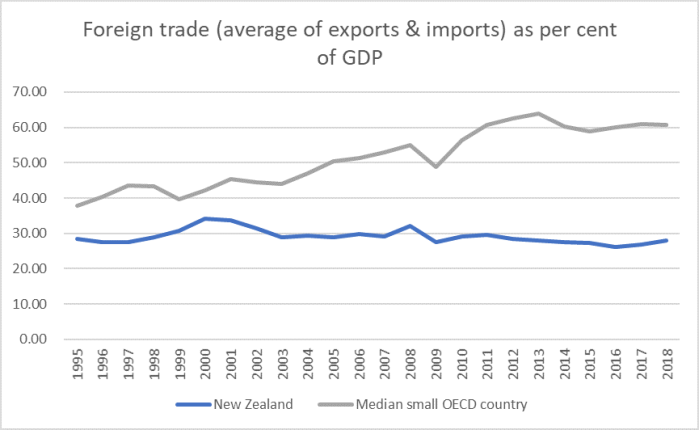

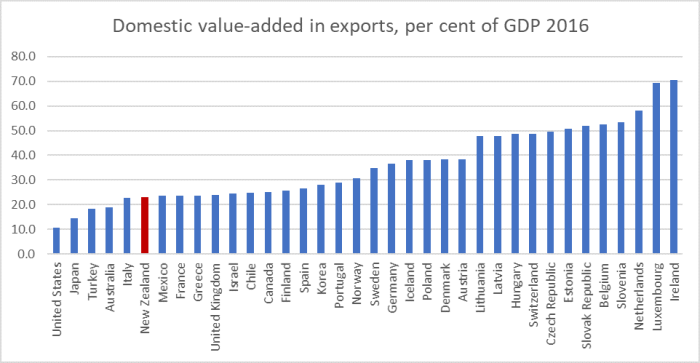

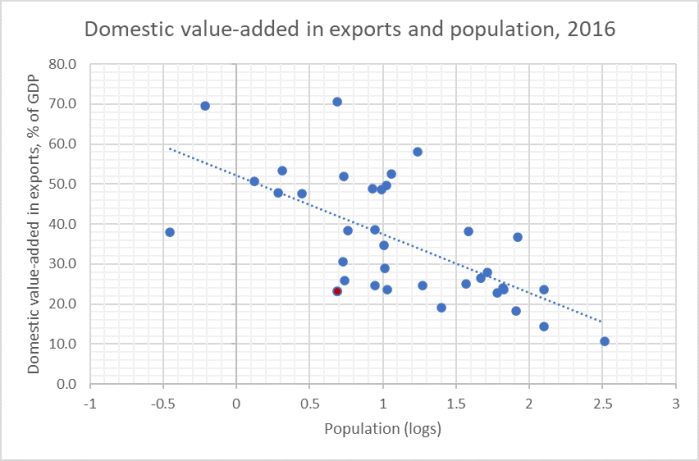

- all else equal, heavy reliance on fiscal policy will hold up the real exchange rate and tends to advantage (a) urban consumers, and (b) inwards-focused New Zealand firms relative to those in the tradables sector. Given that foreign trade as a share of GDP has been falling this century, that skew would not seem well-aligned with what we might need to be a more highly productive economy longer-term.

- and, as noted above, monetary policy takes effect immediately and has a pervasive effect, while leaving individual choices open to each individual and firm.

By contrast, fiscal policy involves politicians’ grubby fingers all over choices about who benefits and how (for example, the proposed temporary RMA reform which might empower projects that get the imprimatur of the Minister, but do nothing for genuine private sector opportunities), and serious policie/projects often taken rather a long time to implement, especially if done well. I was exchanging notes with Tony Burton, until last year deputy chief economist at The Treasury – and occupying a very different spot on the political/social spectrum than I do. He has a fairly brutal and succinct style when he chooses and his comment this morning (passed on with permission) on the notion of national-level “shovel-ready projects” as “complete drivel” caught my eye. It was hard to disagree.

Of course, it is fair to ask if there are things fiscal policy could usefully do that monetary can’t right now (after all, there will inevitably be some fiscal component to any effective and aggressive policy response).

One possibility is that banks might be more hesistant than usual to lend at present. Of course, additional private spending does not have to involve more borrowing, but some would. Governments can take risks private banks might not be willing to, but…….the caution of banks is likely to be largely quite rational (they don’t know the future any more than the government does), and that in turn should be a caution to governments rushing in where the private sector (with more on the line) would not.

Perhaps there really are some very high value projects all ready to initiate – things the government was planning to do next year anyway. To the extent there are some such things, it might be perfectly rational to bring them forward (just as someone who was planning to buy a car next year anyway might bring the purchase forward if the forecast glut of rentals really does hit the market, or someone planning to paint the house next year might do it this year if painters are cheaper).

And, of course, the government may be able to offer something like the sort of “national; pandemic income insurance”, of the sort I’ve proposed: a bit more certainty, paid for through the “premium” of slightly higher taxes in normal times, might support private spending and credit now, complementing what monetary policy could achieve.

As I come to the end of this (long) post, which was partly for me about getting some lines straight, I want to stress that I am not opposed to the use of fiscal policy in this crisis – if anything, in the short-term I have argued for an approach more generous than the government’s to date, and I’ve also suggested another pervasive instrument (a temporary reduction in GST) as one possible component of a whole-of-government stimulus approach.

But when monetary policy options are open but policymakers simply refuse to use them, I worry that too little will be done in aggregate (monetary policy has always been a key part in countering any serious downturn). Perhaps there will be a really big fiscal policy push but, as above, that has a lot of downsides, including that it would materially constrain future policy options in a wide range of areas.

But I suspect that perhaps heeding all the caveats about fiscal policy, the authorities will simply be content to let unemployment linger at unnecessarily high levels for years. That happened after 2008/09, from a relatively low peak of unemployment. It would be shameful if it were allowed to happen again – perhaps especially so if it happened under a Labour-led government.

Fiscal policy should not, and probably cannot, effectively carry the main burden of the huge additional policy stimulus the current situation calls for.

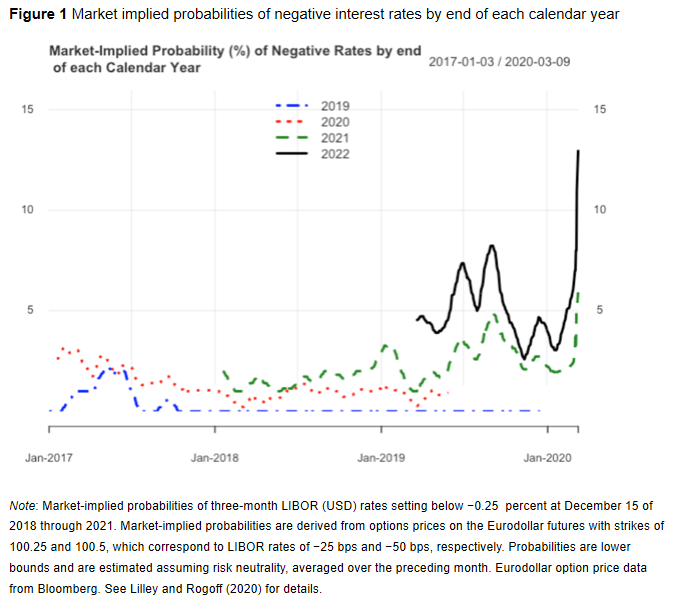

Monetary policy needs to be set to do its job, and do it aggressively. At present, it is simply playing distraction theatre (here and in most other countries). As the golden fetters had to be broken in the early 1930s, so what I’ve called the “paper chains” (so easy to break, and yet central bankers won’t do it) that stop interest rates going deeply negative as they should be for for time need to broken decisively, here and abroad.