Here in New Zealand we are waiting for the details of the government’s promised economic package, which – we are told – will be tightly targeted and focused on the industries that particularly suffered from coronavirus.

Even to write that sentence, is to recognise how absurd a position the government has put itself in. They seem – no real doubt about it, their own words say as much – focused almost wholly on the firms/sectors that suffered from China’s experience with the coronavirus, even as something so much bigger is already beginning to sweep over us. China, after all, if not remotely back to normal, is offering practical assistance to Italy. That outlook was something the Minister of Finance and, even more so, the Prime Minister have consistently refused to face. Perhaps they’ve known it internally – there must, surely, be some good adviserssomewhere – but nothing they’ve said in public has prepared New Zealanders for the reality of what is unfolding, and what is likely to happen in the coming weeks and months. (Our media don’t seem that much better: the Herald today has a full page story on the front cover “The World Faces Reality”, but readers will still have little or no sense that the economies of many countries are about to substantially shutdown.)

Whether or not we get serious outbreaks here – and who aside from the Ministry of Health would be willing to punt on us not – the New Zealand economy will be severely – really really severely – adversely affected. And there is very little that economic policy tools, macro or micro, can do to lean against or mitigate that loss. Economists have talked for years about the benefits of exchange, specialisation, personal interactions etc etc. But for the next few months the emphasis seems likely to be increasingly on keeping your distance, hunkering down. Huge amounts of output just are not going to happen, and there will be hardly a firm or sector not really severely adversely affected.

Whether or not the government’s plans were reasonable when they were first being conceived – and just perhaps they might have been six weeks ago – surely now is the time to bin that package they were planning to announce next week. They need to start over, facing the reality now before us, not the (now rather limited) shock that first faced us (and certainly hit some individual sectors hard).

Sensible policy responses now – whatever they choose to do around further border closures – look much more appropriately focused on immediate crisis management. In other words:

- ensuring the income support is going to be readily and effectively available for the many (especially low income) people who won’t be able to work from home or who will have exhausted their sick leave (and any ex gratia generosity employers may still be able to offer). That might require legislation: if so, pass it,

- ensuring that the food distribution system is going to be reasonably robust if we go through closed-down periods (in an early post here, I recounted an anecdote from an early phase of pandemic planning that scared me then: big supermarkets typically only have 1.5 days of sales in stock at any one time),

- spending/doing whatever can still usefully be done to prepare for possible severe health system stresses (rather than just happy talking the public about how well prepared they are – for 100 cases I’m sure, but not for several thousand).

and so on.

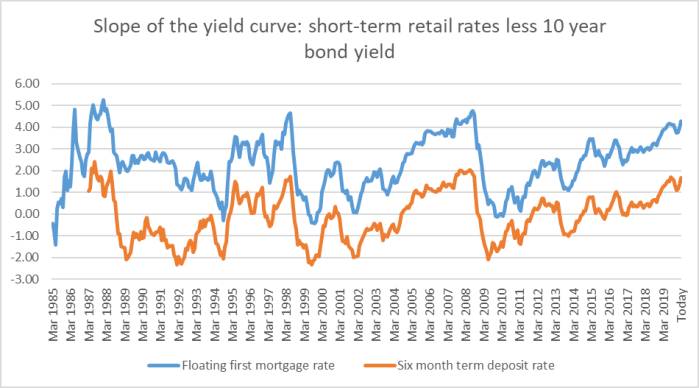

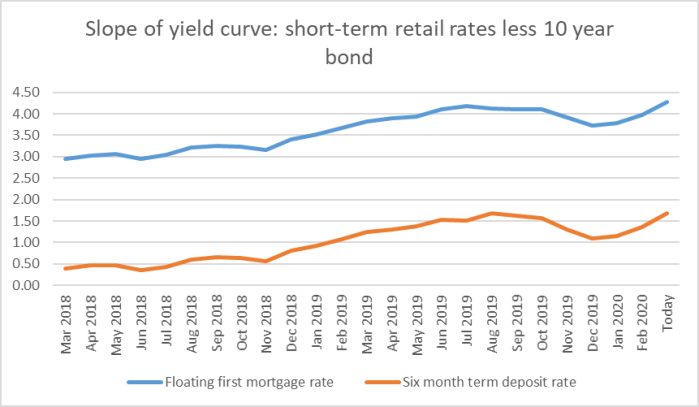

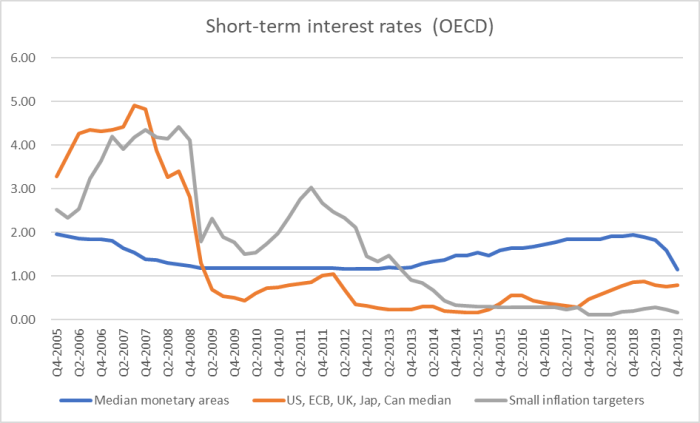

Now, sure there are probably other things to do. The Reserve Bank should be cutting the OCR (for all the reasons I outlined yesterday) and they need to be prepared to roll out liquidity support type operations if financial sector funding stresses start affecting banks here.

But you simply cannot plan to target individual firms, when almost every firm is going to be engulfed. It would inefficient, unmanageable, and would simply to fail to recognise the magnitude of the coming losses.

And there is no point in thinking of huge fiscal outlays, as general stimulus, right now. If the government was going to plan to actually purchase physical goods and services well (a) what would it do with them?, and (b) soon enough, the capacity of the economy to deliver much (workers at work, functioning distribution systems) are going to be severely impaired. And – the more likely option – simply putting money in people’s pockets, whether by cash grants or tax cuts (GST or low income thresholds on income tax) aren’t likely to achieve much systematically useful either. For a start, if you are sensible then in such a climate you won’t want more people eating out (say) or moving around holidaying, or going out to big sports matches or concerts (classic discretionary items). And even if online retail really was still fully functional locally, it just isn’t that large a share of New Zealand retail. More generally, quite-rational fear and uncertainty about the future will have people pretty reluctant to spend anyway. That is sensible and prudent, and not really something governments should now be trying to undo – even if our happy-talking Prime Minister was the other day encouraging people just to go out and spend. We need to start thinking in terms of the deepest contraction in economic activity any of us – except perhaps the handful still alive who experienced the Great Depression- have ever seen. It is the price the world is going to pay to “flatten the curve” (something we’ll come back to).

Big stimulus is probably going to be appropriate and required as and when the worst of the virus is past us, and people are genuinely and rationally able to see some light at the end of all this, building on the fundamentals already at work by then, speeding up the recovery. Ideally, that would be a mix of fiscal and monetary policy, bending over backwards to help get economic activity levels back to normal. So use the time now – you’ll have plenty – to prepare for that sort of strategy (and perhaps for the inevitable bailouts and recapitalisations our politicians will find themselves unable to resist – anyone suppose that if it comes to that governments of either stripe would let Air New Zealand fail (but I hope at least they wipe out the private shareholders if it does happen)). It might even be time to consider changing a few individuals at the top (poor generals are found out in wartime and, in good armies, quickly replaced).

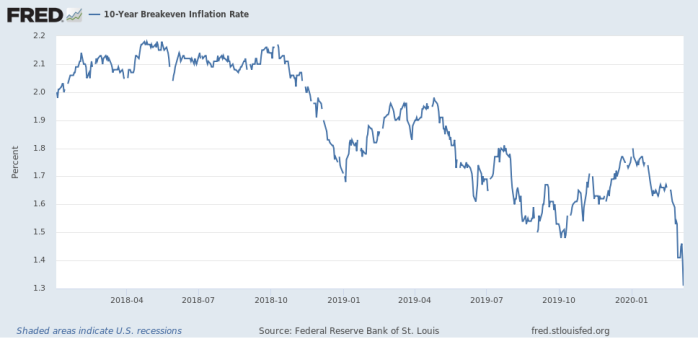

On the fiscal side, make sure – for example – that a universal lump sum cash payout to all residents could be made (from the outside hard now to see how it could be done). Ensure that a temporary GST cut could be implemented quickly and smoothly. And insist that the work is done to largely remove the near-zero effective bound on lower interest rates. It can be done – it should have been done, here and abroad, five years ago – and failure to act will simply unnecessarily hold back eventual recovery (and reinforce those downside risks to inflation expectations that I’ve often worried about here).

One of the key things we all have to recognise is that this situation is not going to be resolved any time soon. For hints of that we can look to China. Sure the new case numbers and new deaths have come right down – more infections this week, I think, from arrivals from other countries than locally – but nowhere are things back to normal. In Wuhan it seems that recovery has barely even begun. Look at successive waves of things like we are now seeing on Italy – or early signs in other countries too – and there is going to be no confidence (including about travel) and no certainty for a long time.

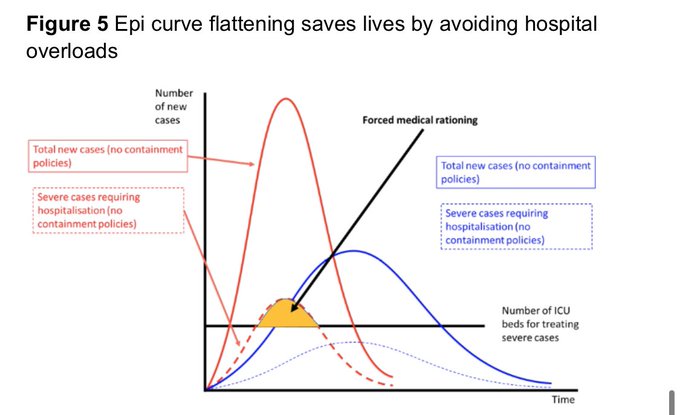

But perhaps even more importantly, remember that the virologists etc talk about the goal of current interventions being to “flatten the curve” . This is perhaps the best version of the stylised chart I’ve seen, in a new article from the economist Richard Baldwin.

Perhaps it is a little cluttered, but it is trying to convey a lot of information.

The solid red line is a stylised representation of how new case numbers would look if there was no containment (given that there is no effective treatment). You’ll have heard of experts talking of how if that happened perhaps 50 per cent of the world’s population would be infected before too long, since none of us has any natural immunity and the virus seems to spread easily.

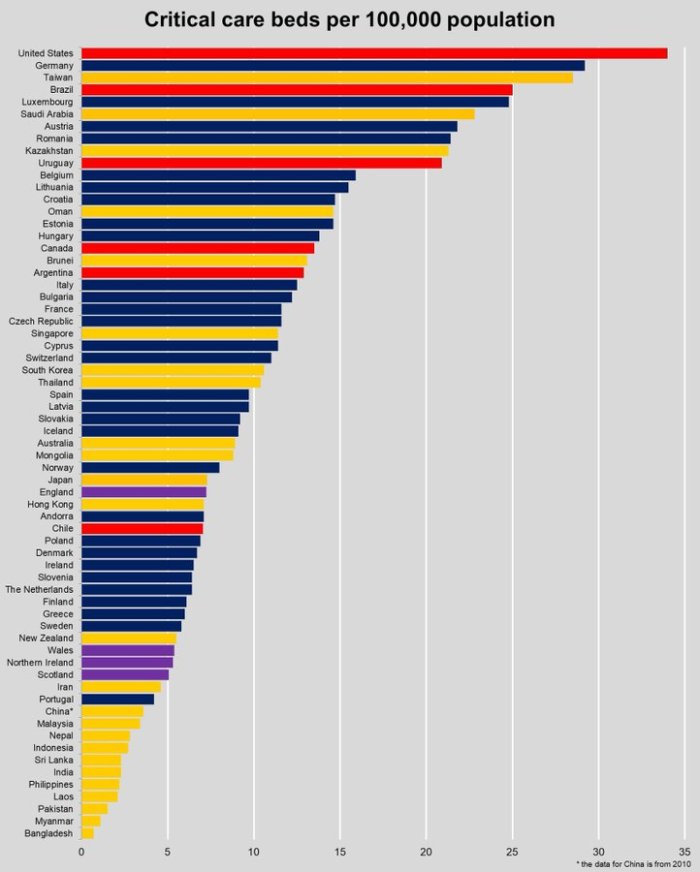

The real worry in that scenario is the dotted red line – people needing ICU-level care. And this perhaps is where the chart is too sanguine. On this version, the area under the dotted red line, and yet above the ICU bed capacity, is small relative to the total ICU demand. But if 5 per cent of cases need ICU-level care (seems about right from what I’ve read) then it is worth remembering that New Zealand, for example, has about 175 ICU beds. Perhaps with valiant efforts those numbers could be doubled in an emergency – but doctor numbers can’t – but even that would mean that, if no one else was in an ICU bed at all, our system would be overwhelmed at 7000 cases at the same time (5 per cent of 7000 being 350). That might seem a lot of cases, but recall that 50 per cent of New Zealand’s population is 2.5m people.

So trying to flatten out the curve is about trying to avoid the forced medical rationing already evident in the high-quality northern Italy health system and, presumably in the process, reduce the overall death toll (very old people will get treatment and as a result some will live who might otherwise have to be left to die). If the curve could be flattened out, by aggressive containment etc measures, the aim – highly stylised – is to produce something like blue line, where the ICU demand never quite exceeds the physical capacity.

But what isn’t often mentioned – although it is quite clearly implicit in the stylised chart – is that the aggressive containment measures don’t necessarily alter the likelihood that – at least unless there is a widespread vaccine available next year – many of us will still get it in the end (something like 50 per cent is still the number – the sort of thing Angela Merkel said to the German people the other day). It is just a matter of time, of stretching things out, and (thus presumably) of repeated waves or outbreaks in different physical locations. Take Italy as an example, the current situation looks horrendous, but case numbers are not even close to 1 per cent of the population.

And, unless that narrative changes markedly as we learn a lot more, that seems likely to be the sort of scenario every country faces, in one form or another, for the time being. There is nothing to suggest – since no likelihood of a vaccine in that time – that the problems/risks/disruptions will ease this year. And the end of the year is still 9 months away. Turning back to the economics, a great deal of economic output and wealth can, and probably will, be lost in that time. It means – sadly – that there is likely to be plenty of time to think about planning for serious stimulation as we get to a recovery phase. How many people are going to be keen to book travel, even if borders stay open or re-open and flights are still there? How many people are going to be keen to spend (precautionary savings will look very rational for many if they still have an income)? And who is going to be ready to commit to start investment projects, even if either debt or equity funders were willing to release the funds needed?

It isn’t hard at all to see New Zealand’s GDP for the rest of the year being perhaps 10 per cent lower than otherwise (that isn’t a forecast, just an attempt to suggest that the ballpark numbers people should be working with are very very large. That alone would $25 billion of income lost that is mostly never coming back – even if next year we resumed the pre-crisis growth/income path – and losses which have to be (a) borne and (b) distributed. There will be significant business failures. There will be heavy job losses. And, despite my scenario, it is not as if anyone – government or private – can safely plan on the losses being limited to this year and everything being pretty much normal thereafter.

There is a pressing need for the Prime Minister and the Minister of Finance to get real about the magnitude of the economic (and probable social) disruption we are going to face, the price we pay – even though much of it will be out of New Zealand’s control – to manage the virus. Front the public and explain why now is no time for a limited backward-looking package, but for something much more dramatic and whole-of-nation crisis focused, with a time horizon that stresses that “normal” will almost certainly be some considerable time away.