A few weeks ago I received an invitation from the OECD to this (Zoom) event

Going for Growth is one of the OECD’s flagship economics publications in which, among other things, they identify for each member country what their indicators and models suggest should be structural reform priorities. As the title suggests, the focus is – or at least used to be – productivity, labour market utilisation and the like. The latest New Zealand note, released in May, is here. There is often a fuller treatment in the OECD’s Economic Survey for each country, which they are working on now, having done the rounds (by Zoom) of New Zealand officials and other people (me included) a couple of months back.

Yesterday’s event had potential. The Director of the OECD’s Economics Department spoke, as did one Productivity Commissioner for each of New Zealand and Australia, and then three non-government economists (two from Australia, one from New Zealand), followed by questions from the audience. I wasn’t able to stay to the end, but heard all but one of the presentations (and the one I missed was by an Australian bank economist, presumably focused on Australia). They said that a recording of the event will be posted on the OECD website but as of this morning it didn’t yet appear to be there.

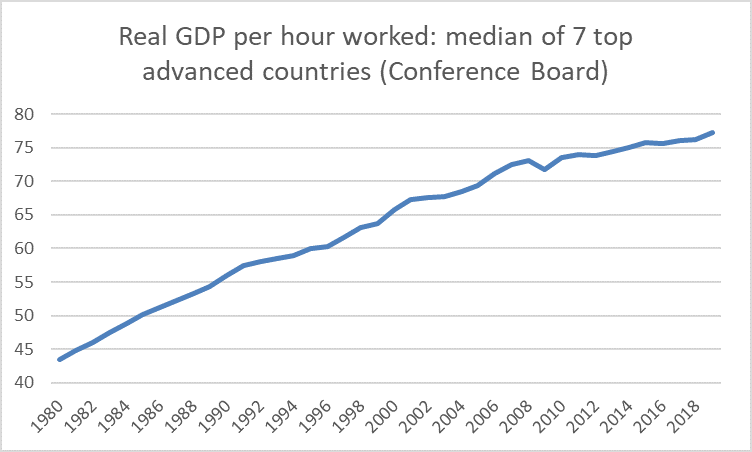

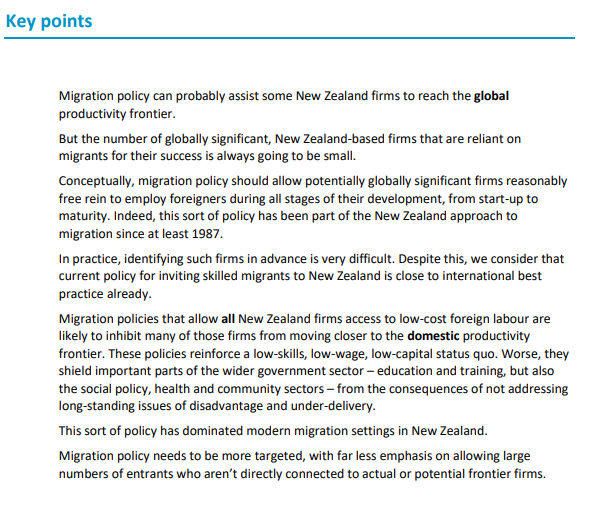

First up was Luiz de Mello from the OECD. With the New Zealand note having opened highlighting how far behind productivity lags in New Zealand one might have hoped for far-reaching policy suggestions. Instead, we got a boringly familiar list, most of which make sense but – realistically – none (individually or collectively) offer the prospect of dramatic macroeconomic change. De Mello was speaking about both New Zealand and Australia, and given how far behind Australia New Zealand average productivity lags that probably further limited the value. Anyway, his list was as follows:

- he highlighted a component of the OECD’s Product Market Regulation (PMR) indices, suggesting that for both New Zealand and Australia licences and permits (presumably cost or timeliness) were much more of an obstacle than in the top 5 OECD countries (Australia worse than New Zealand),

- he highlighted the bad scores both countries get on the OECD FDI restrictiveness index (New Zealand worse than Australia)

- he highlighted the variance in PISA scores, which is higher in New Zealand and Australia than in most small advanced countries and the UK (having, somewhat to my surprise given our slide down the PISA rankings, noted in the report itself that New Zealand “educational achievement is high on average”.

- he highlighted how high housing expenditures are relative to the OECD for the bottom quintile, and

- he highlighted the OECD’s view that too much of greenhouse gas emissions in both Australia and New Zealand were “underpriced”.

Beyond that, they seemed keen on a large social safety net – addressing “child poverty” directly, and smoothing the income of the unemployed.

Most commentators in New Zealand probably think the government has done little useful structural reform – with a growth/productivity focus – but the OECD begs to differ, talking in their final paragraph of the “significant actions” taken in recent years in key priority areas. Weird housing tax measures, for example, seem to win favour from an organisation that used to favour neutrality in the tax system.

So the session wasn’t off to a great start at this point. Whatever your view on pricing emissions, increasing those prices is not going to boost incomes and productivity, and the other four items – while each no doubt pointing towards useful possible reforms – are simply not likely to be game-changers.

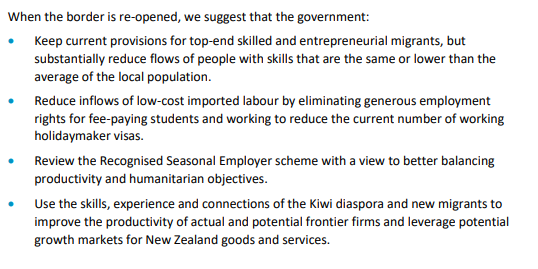

The next speaker was one of the New Zealand Productivity Commission members, Gail Pacheco. She too started with a bow to history, highlighting our decades of languishing productivity performance. She chose to pick up some points from a couple of the Commission’s recent reports. From the Future of Work she noted, reasonably enough, that New Zealand probably did not have enough technology and that a successful New Zealand economy would see more technology adaptation and diffusion, but she offered no thoughts on what changes in the economic policy environment might create conditions in which firms would find such investment worthwhile. She seemed more interested in the Commission’s social insurance idea – now being picked up by the government – which would pay more to people unemployed at least in their first few months of unemployment. There might be a case for such a policy – I’m pretty ambivalent – but in a country where it is not that hard to close business and lay off staff, it has never been obvious (and Pacheco made no effort to elaborate yesterday) how this had anything to contribute to creating a climate supporting higher business investment and stronger productivity growth.

She then moved on to the recent Frontier Firms report and briefly ran through a list of things she thought would help, including

- significant (government?) investment in a handful of chosen focus areas/sectors,

- coordinated effort across government

- everyone working together across the wider community,

- transparent and adaptive implementation,

all of which, she claimed, would lead to (the current government’s mantra) a “more sustainable, inclusive and productive” economy.

Now, in fairness, each speaker did not have a great deal of time, but there was nothing in Pacheco’s speech that suggested that she had got anywhere near the heart of the issue, had any real sense of the market and private sector, or saw the answers as anything more than well-intentioned (we hope) ministers and Wellington officials trying more (seemingly) smart interventions, preferably without pesky disagreement or robust accountability (she talked of long-term predictable policies).

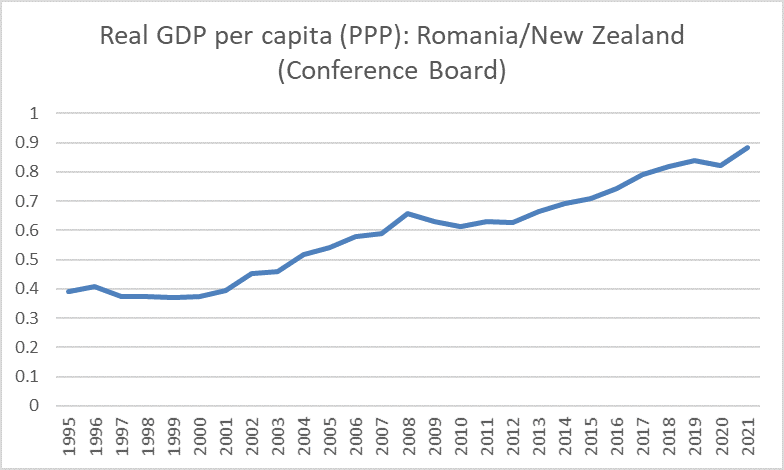

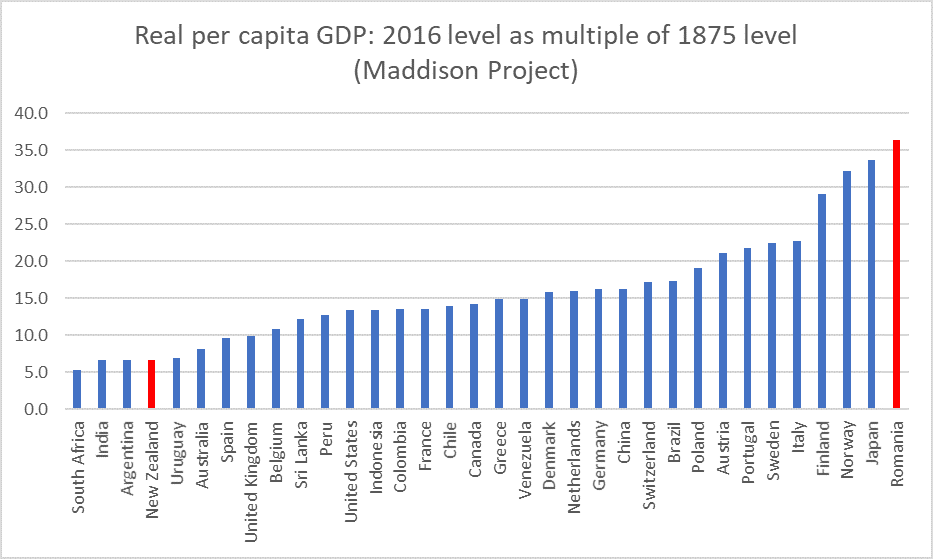

Pacheco was followed by one of the Australian Productivity Commissioners, Jonathan Coppel, who seemed to have a rather more robust grasp of the economy. Interestingly – to me anyway, it wasn’t his point – he opened with a chart using new historical estimates suggesting that New Zealand’s decline (relative to both Australia and the US) can be dated earlier than Pacheco suggested or than the previous Maddison estimates suggested. His point was that Australia has made no real progress in closing their (smaller) productivity gaps to the US – US 30 per cent ahead of Austraia – repeating a line often heard out of Australian recently that the 2010s were the worst decade for Australia – growth of GNI per capita – for six decades. He seemed keen to stress the importance of building on the reforms of the 80s and 90s, rather than discarding them, but it wasn’t that obvious how his suggestions – reduced reliance on income taxes, good regulatory practice, and a focus in post-school education/training on competition and lifelong learning – were likely to be equal to the task. He did stress the idea that economists needed to do more communicating with, and persuading the public, re the case for change, not leaving everything to the politicians.

The next speaker was an Australian private sector economist, Melinda Cilento who – she spoke very fast – had a long list of things she wanted in Australia, almost all of which seemed peripheral re longer-term productivity, and several of which were simply out and out redistribution (for which there may or may not be a good case in Australia).

The final speaker I heard was Paul Conway, formerly of the Productivity Commission and now chief economist of the BNZ. HIs was perhaps the most promising of all the presentations, even if he seemed implausibly optimistic when he talked of the “once in a lifetime opportunity” to fix the New Zealand economy, end its “muddling along” performance, and (the government mantra again) deliver a more “sustainable, productive and inclusive economy”. He didn’t point to a single sign that either the government or their Opposition were interested in anything serious along those lines.

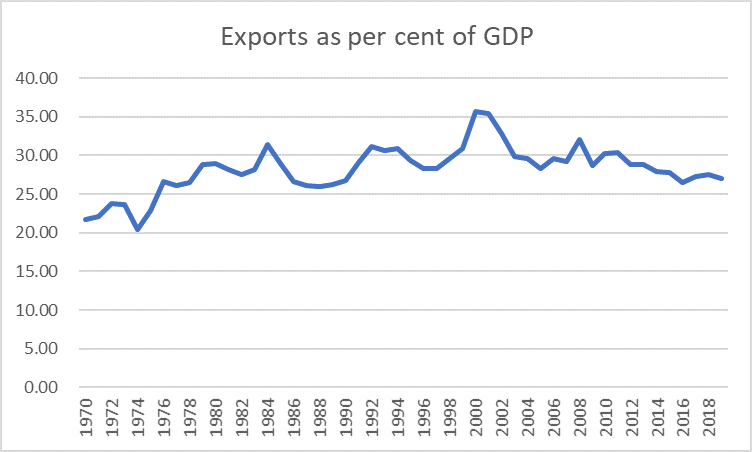

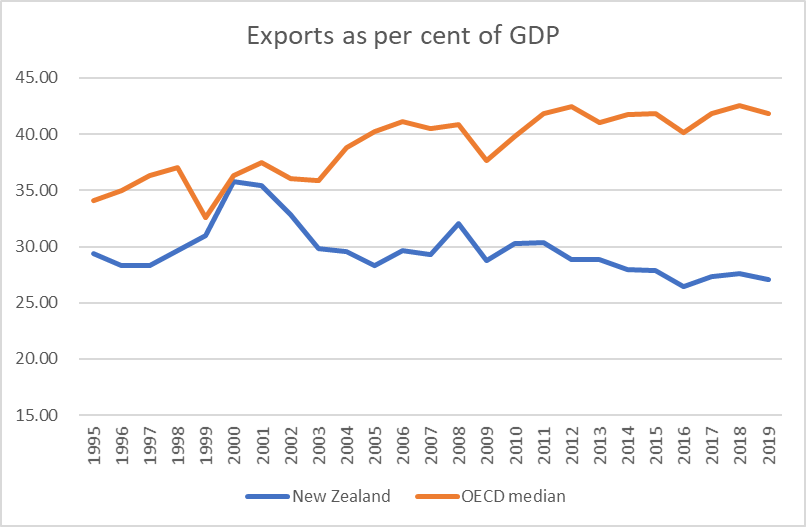

But he did highlight the need to think carefully about policies that “fit us here” including taking explicit account of our remoteness. He called for a much deeper understanding of the problem, for a priority on good economic research, for the development of credible narratives that explain our underperformance and ground sold recommendations for policy changes. Much of this reflected Paul’s efforts at the Commission, including the narrative he drove (and wrote) – which I wrote about here. In some of his work, Paul has expressed sympathy for aspects of my story around immigration policy, and noted that he welcome the current Productivity Commission inquiry.

Some of his specifics I’m less convinced of, and he noted that his own views have a lot of overlap with the OECD’s Going for Growth proposals (see above for how limited they are) – while noting that he had been involved in the very first Going for Growth, back in 2005 when he worked at the OECD, and the ideas mentioned for New Zealand then were much the same as those now.

Conway ended with a call for specifics, for work with policy people and lawyers, and for a lot more emphasis on communications and doing the “hard sell” to our “lawmakers”, claiming that as he had got older he was increasingly convinced that the task was mainly marketing good ideas – “we know what needs to be done” – and building consensus, rather than devising new ideas.

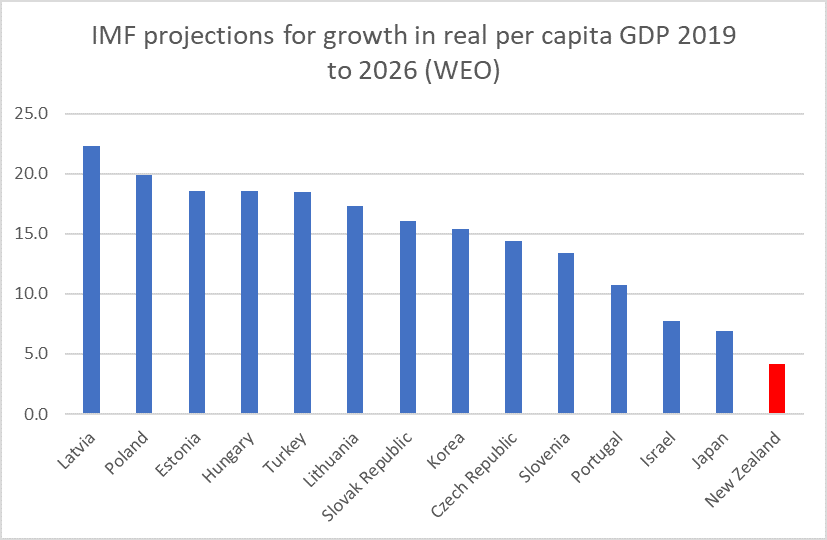

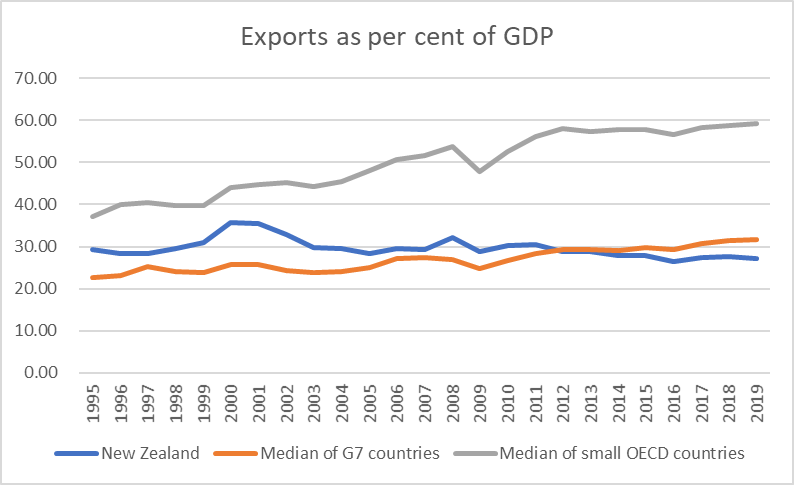

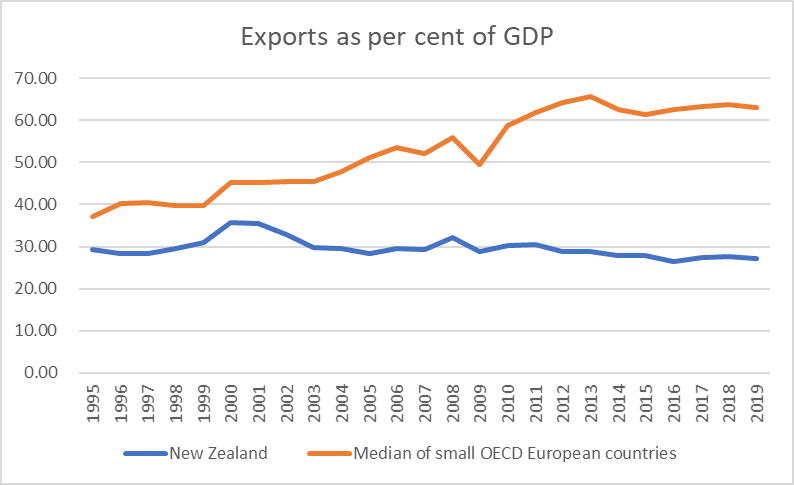

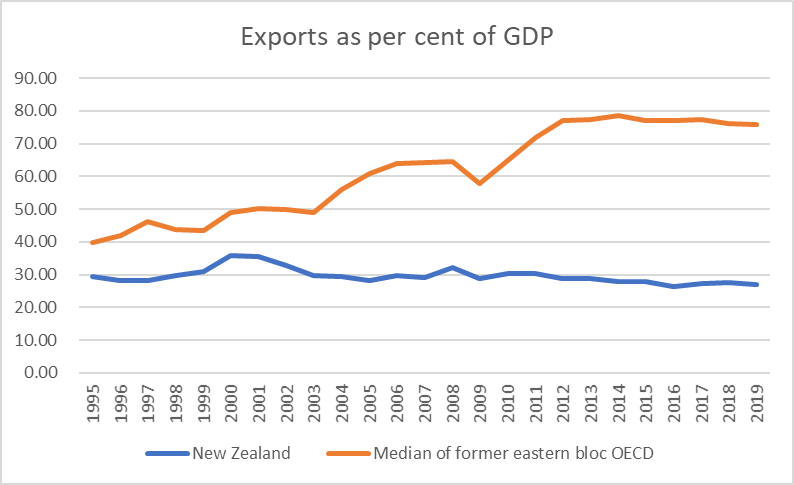

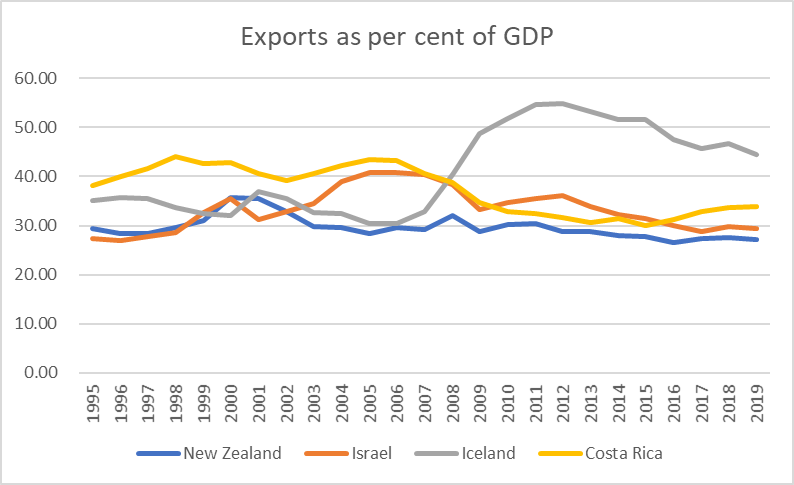

And at that point I had to leave. Perhaps the follow-up questions generated some startling insights, but probably not (and I have no idea how many New Zealand focused people were even in attendance). My biggest criticism is for the OECD – which, after all, put the event on and their ideas on the table – who seem simply inadequate for the task pf offering serious, analytically and historically grounded, advice to New Zealand authorities (or others here who might want to champion actually doing something about decades of failure) on making a dramatic difference to economywide productivity outcomes here. It must be more than a decade now since I attended a workship in Paris where OECD staff presented modelling suggesting that on their standard prescriptions New Zealand should be much much richer and more productive, which suggested that there was something quite seriously wrong with their model, at least as applied to (really remote) New Zealand (I’ve long held the view that – unsurprisingly – the OECD has model and mentality that probably primarily adds value in small European countries (a lot of those in the OECD). One might argue that it doesn’t matter, since no politician here is serious about change (at least for the better, the current government is pursuing paths likely to worsen things) but that isn’t really the point of the exercise. As various speakers noted yesterday socialising ideas, persuading people, showing what might be possible are all a significant part of a prelude to action (just possibly one day). I disagree with Paul Conway that there is consensus about what needs to be done: there clearly isn’t, and may never be, but we might expect an entity with the resources and expertise of the OECD to be offering a lot more insight, a lot more recommendations commensurate with the scale of the failure, than we are actually getting.

As for the New Zealand Productivity Commission, they seem to be on a downhill path, more interested in cutting pies differently than growing them, too confident in politicians and officials, and more inclined to wishful thinking than serious analysis indicating what might really lift our productivity levels back towards the top tiers of the OECD. I guess there is cause and effect at work, but it is no wonder politicians aren’t serious about change when the advice they get from high-powered official and international agencies is so thin. It is a lot easier to just cut the pie differently and dream up more announceables, but reversing the relative productivity decline is really what matters for our future material wellbeing – those at the top and those at the bottom – ours, our children, our grandchildren. If we don’t fix it, exit will remain an increasingly attractive option for many.