It is a good rule after reading a new book, never to allow yourself another new one till you have read an old one in between.” C S Lewis

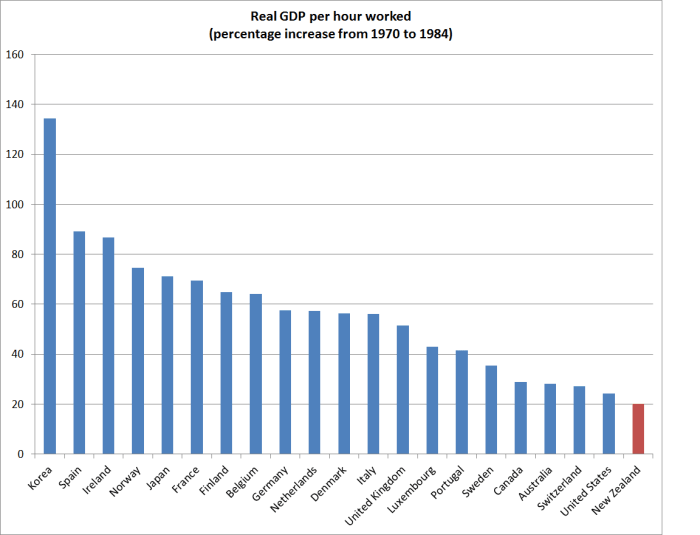

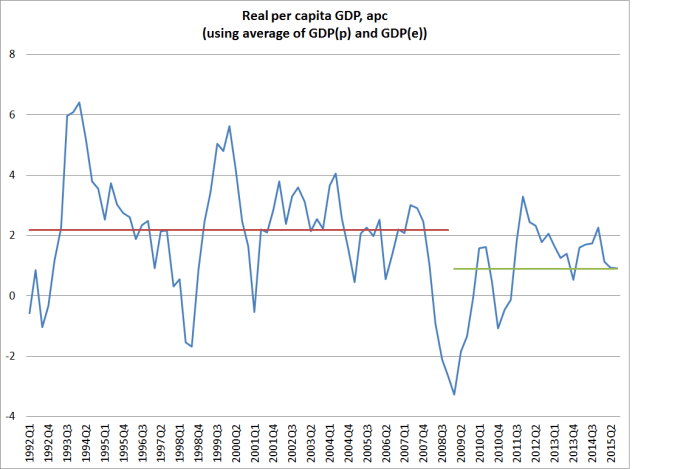

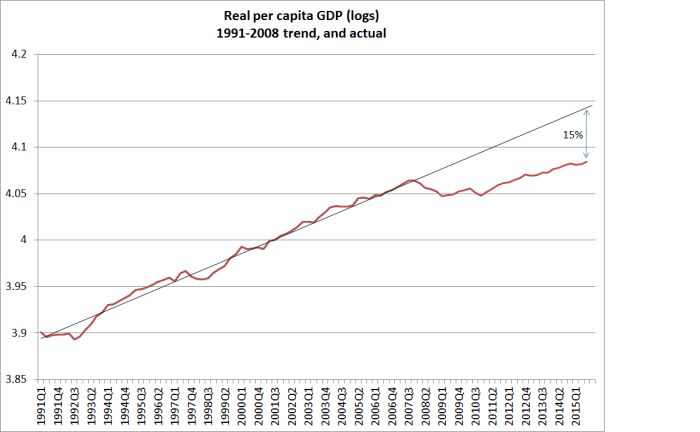

Over the weekend I was reading the 2nd edition of Portrait of a Modern Mixed Economy: New Zealand, published in 1966. The original Portrait, by Professor (at Canterbury) C Westrate had been published in 1959, and the second edition was a simpler, shorter, updated version completed by Westrate’s son after his father’s early death. I’m fascinated by anything on New Zealand and its economy from this period, because it was a time when New Zealand was widely regarded as still having some of the highest material living standards anywhere in the world. There were already intimations of uncomfortably slow productivity growth (relative to other advanced economies) appearing in official and quasi-official reports, but no real hint of the deep decline in our relative living standards that was to follow.

To read such a book is also to be reminded just how remarkable the unemployment record was. For all the distortions that went with it, there was something impressive about sustaining an unemployment rate at around 1 per cent or less for decades (on the Census measure, which approximates the current HLFS approach). And they weren’t, mostly, make-work public enterprise jobs.

Of course, the distortions were numerous. Westrate quotes data that in 1964 government consumer subsidies were equivalent to 35 per cent of the retail price for butter, 40 per cent for milk, 55 per cent for bread and 65 per cent for flour. The subsidies were a bit lower than they’d been a decade earlier, but it was to be another couple of decades before they were completely removed. And while I’d come across the (statutory) raspberry marketing body previously, I hadn’t known that we had a monopolistic Citrus Marketing Authority, which controlled all imports and the sale of all local production. Odd as those measures now seem, I wonder what of the current regulatory state people in 2066 will look back on in puzzlement? How could they, our grandchildren may wonder.

In the 1960s, the Reserve Bank – and monetary policy – was firmly under the control of the government of the day. But I was reminded of the way that wage-setting was then officially delegated to unelected bureaucrats – in this case, the Arbitration Court where employer and employee representatives usually neutralised each other, leaving key decisions on basic wage structures to a single judge. As Westrate notes, it is debatable quite how much sustained impact the Court had, since labour market fundamentals matter and the Court only set minima. But in some respects the same could be said for the Reserve Bank: interest rates are ultimately set by fundamental forces shaping savings and investment preferences, but the administrative choices of officials matter in the shorter-term.

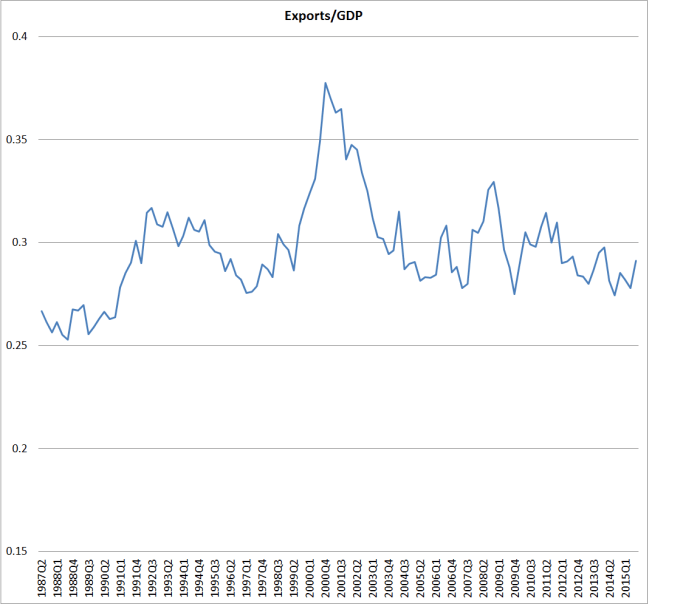

But what I really wanted to comment on today was the discussion of New Zealand’s external trade.

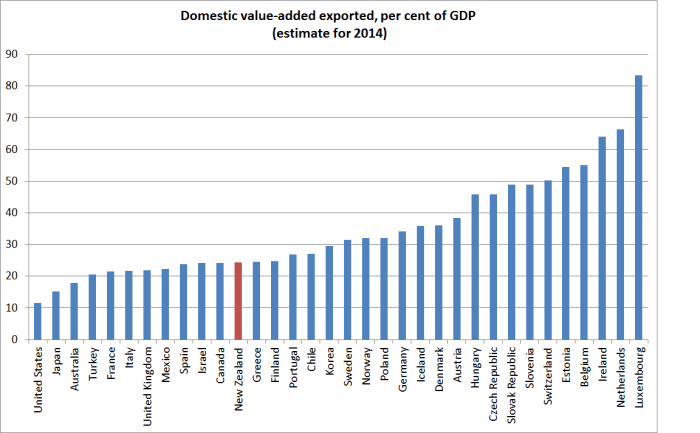

Westrate notes that exports accounted for a higher share of national income than in most trading countries – “consistently near the top of the list”. So far, so conventional – I wrote a while ago about Condliffe’s observation a few years earlier that New Zealand in the 1950s had had among the highest per capita exports in the world. But what caught my eye was that Westrate introduced a explicit discussion of how external trade might be even more important in New Zealand than it appeared, because of the high share of domestic value-added in New Zealand exports, mostly “agrarian commodities”. Westrate was Dutch and had previously been a professor at one of the Dutch universities, and he notes that although the Netherlands, for example, has a higher export share of its economy than New Zealand “it is known that exports from the Netherlands contain a good deal of foreign value.” As he notes, the data didn’t exist to do the calculations, and indeed it is only in the last few years that the OECD and WTO have started producing good cross-country data in this area. The story about the high domestic value-added share in New Zealand’s gross exports is now conventional wisdom, but probably wasn’t in the 1960s.

Having said that, if the story that New Zealand was one of the countries with the highest trade share in the world had once been true – and quite possibly it was in the 1920s – it doesn’t look as though it was in fact true by the time Westrate was writing – which should not be too surprising given the heavy cloak of industrial protection New Zealand had put in place, that tended to reduce both the import and export shares of our economy. Books and official reports from the period often compare New Zealand with the US, UK, Australia, Canada, France and Germany. And for many purposes, comparisons with those countries might have been quite enlightening. But when it comes to foreign trade, it is now well-recognised that large countries typically do less external trade as a share of GDP than the small ones do. There are more markets, and more suppliers, at home than is likely to be the case for a small country. When a large country has a very large trade share – China pre 2009 and Germany now – it is often a sign of other imbalances.

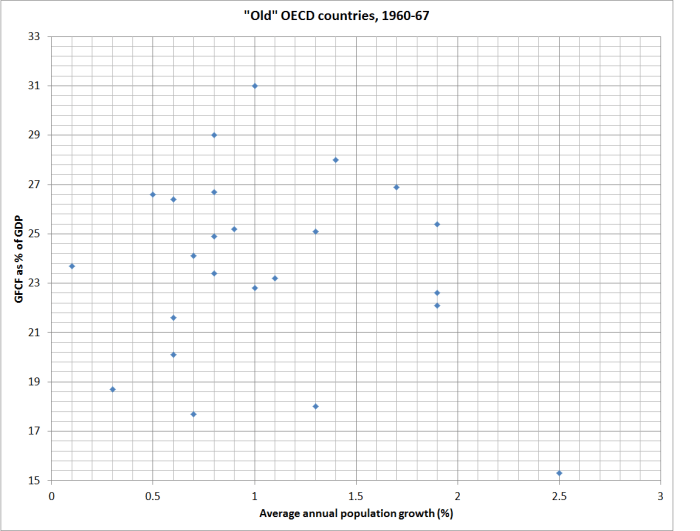

Finding comparable long-term historical data is always a bit of a challenge. But I had on my shelves a 1990 OECD compilation volume of historical statistics, with data on a wider range of variables (including exports of goods and services as a share of GDP) for 1960 for the “old” OECD countries.

For New Zealand exports as a share of GDP in 1960 were 22 per cent.

For the smaller Europeans (Netherlands and smaller), the proportions were:

|

Exports (good and services) as a % of GDP, 1960 |

| Austria |

24.3 |

| Belgium |

38.4 |

| Denmark |

32.2 |

| Finland |

22.5 |

| Greece |

9.1 |

| Iceland |

44.3 |

| Ireland |

31.8 |

| Luxembourg |

86.7 |

| Netherlands |

47.7 |

| Norway |

41.3 |

| Portugal |

17.5 |

| Sweden |

22.9 |

| Switzerland |

29.3 |

With a median of 31.8 per cent. (By contrast, for the G7 countries, the median was 14.5 per cent.)

As Westrate noted, we don’t have the data to know what the share of domestic value-added was in exports in 1960. The first OECD date are for 1995. But even by then, when domestic value-added of New Zealand’s exports was 83.2 per cent, the median for those smaller European countries was 76.4 per cent – lower than New Zealand, but not an order of magnitude different. If – heroically, and really only illustratively – the same value-added shares had prevailed in 1960s, New Zealand’s export value-added would have been around 18 per cent of GDP in 1960, while the median European country would have been around 23 per cent of GDP

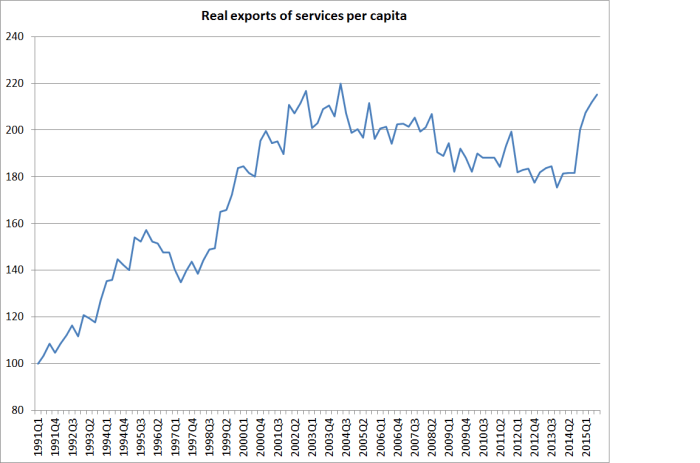

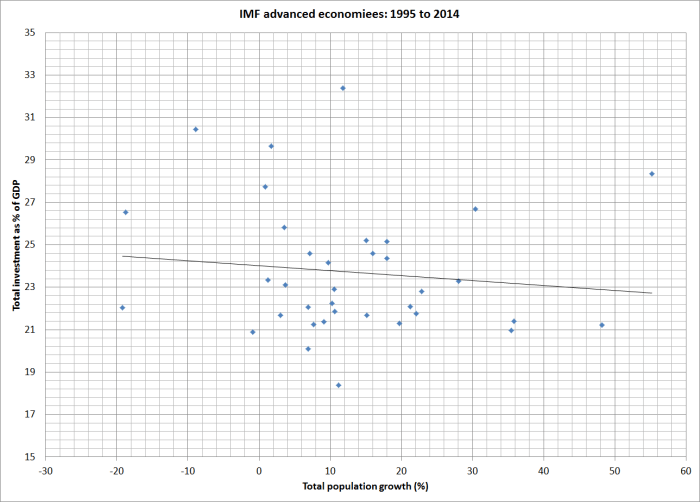

What of the present? The latest OECD-WTO value-added data are for 2011 (I wrote about them here). Over the intervening 16 years, the domestic value-added share of New Zealand’s exports barely changed, while the median of that same sample of smaller European countries had fallen sharply, to 67.3 per cent, as the importance of global value chains (especially within continental Europe) has increased sharply.

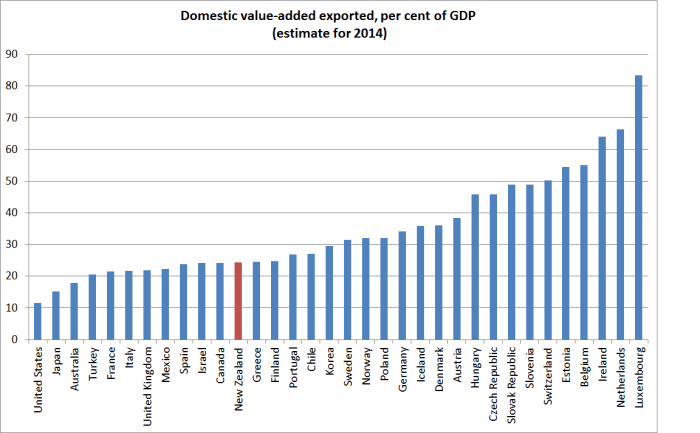

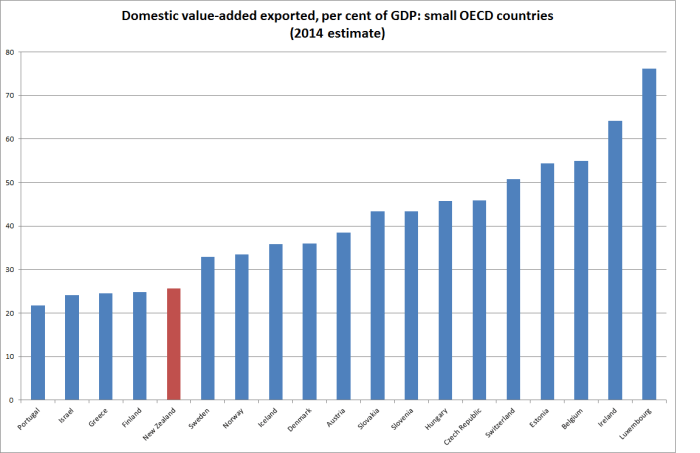

For the more recent period, we have much larger set of OECD countries to look at (many of them also quite small). The data for exports as a share of GDP is available for 2014. If we apply the 2011 domestic value-added share of exports, to the 2014 data on total exports, we get this pattern of domestic value-added in exports as a share of GDP.

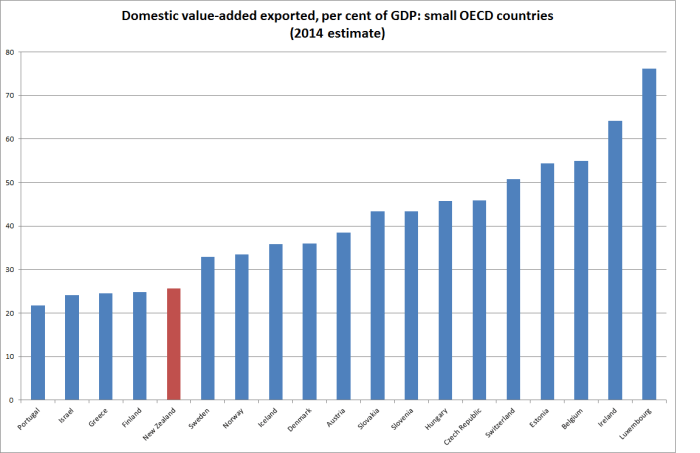

But what about “small” countries? If we rank the OECD countries, there is a natural break between Belgium with 11 million people and the Netherlands with 17 million. Here is the chart for the 19 OECD countries with populations of 11 million people or fewer (nothing would be altered by including the two countries with around 17 million).

New Zealand isn’t the lowest ranking country on the chart, but those that are worse aren’t generally ones we would want to emulate. Greece and Portugal speak for themselves – and, indeed, the export shares for those countries are flattered by the weakness of the domestic economy at present. Israel has had as poor a productivity record (and as modest per capita GDP) as New Zealand. Finland had been performing well until 2008, but since then it has been one of the worst-performing economies in Europe, and its exports as a share of GDP have fallen sharply.

A customary response to the New Zealand data is to point out that remote countries tend to do less international trade that less remote ones. By almost any measure, New Zealand is among the most remote of these countries. But if trade with the rest of the world is a significant part of how smaller countries get and stay rich – maximising the opportunities created by their ideas, institutions and natural resources – shouldn’t we be more bothered about the implications of our remoteness? New Zealand just isn’t a natural place to build lots of strong businesses, unlike – say – Belgium, Denmark, Austria or Slovakia. That doesn’t mean such businesses can’t be built at all here, but it is an uphill battle.

And it has probably become more of an uphill battle in the last 20 to 25 years. Gross exports have risen hugely among many of the European countries since 1995, but so has domestic value-added from exports (all as shares of GDP). And it isn’t just the former communist countries emerging – in Denmark export value-added as a share of GDP has risen by 7 percentage points, and in Austria the increase has been 12 percentage goods. In New Zealand, by contrast, there has been almost no change. This isn’t some mercantilist story in which exports are good for their own sake – but finding more markets for more stuff, enables people at home to import and consume more of other stuff.

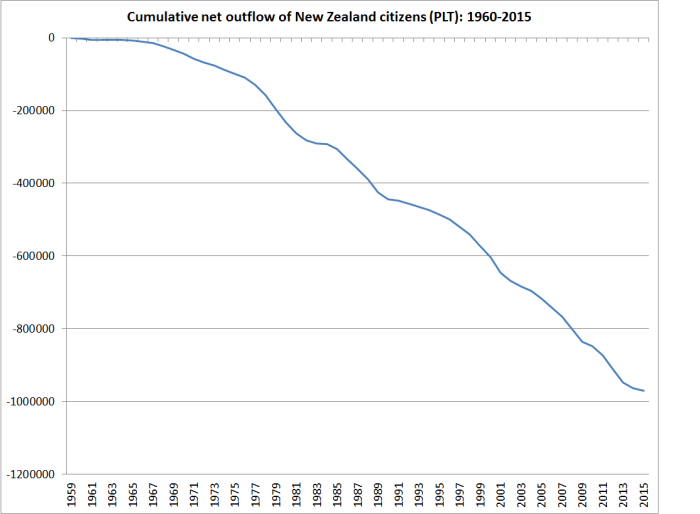

As I’ve noted before, it looks as though New Zealanders have been responding – for decades now – by moving to other countries, especially Australia, where the income prospects have been perceived as stronger. But our governments have wrong-headedly sought to bring in lots more people, to more than replace those who are leaving. Somewhat to my surprise, the quality of many of those people now seems questionable at best – recall the most popular occupations for skilled migrants. But the real issue should probably be whether continuing to aggressively pursue a larger population, as matter of policy, makes sense in a country that is so remote, and where not even the soil is that naturally fertile. It is, in many respects, a nice place to live, but the ability to generate top-notch advanced country incomes for even the current population must be seriously questioned. To do so, a small country needs to be able sell a lot more of it makes to the rest of the world than has New Zealand has been managing – in the 1960s or now.

The government’s exports target rather crudely recognises the issue, but they have no credible economic strategy that might bring about such a transformation.

(And while climate change is not an issue that I pay much attention to, less rapid population growth through reduced immigration targets might also be a rather cheaper way of meeting somewhat arbitrary emissions targets.)