As I noted a few weeks ago, about fifteen years ago Struan Little, then at The Treasury, sparked my interest in Uruguay, and comparisons between its long-run economic performance and that of New Zealand. When I wrote that earlier post, I searched around to see if anything Struan had written on New Zealand’s economic performance was on the web. Nothing was now, but it became clear that something had been. Various old articles (eg here) referred to a paper released at the end of 2001 by Treasury, drawing “lessons from the losers” – other reasonably advanced. reasonably democratic, countries, or regions, with some similarities to New Zealand, which had also done poorly. The paper had even been cited by the IMF in one of their Article IV reviews of New Zealand.

The author no longer had a copy of the paper, but fortunately Treasury was able to track it down for me. The OIA response should be on their website before too long, but in the meantime here is the document itself, “Growth and Policy in other countries: lessons from the losers”, dated 31 October 2001.

Lessons from the Losers by Struan Little

As Treasury is at pains to note, this was a personal thinkpiece, and although it was publicly released back in 2001 to influence debate and discussion, it was never finalized. It isn’t a long paper (12 pages of text), so couldn’t cover everything, or document every caveat or qualification, but papers like this help us see the issues in slightly different ways. It is to Treasury’s credit that they made space for the work to be done, and then put it out proactively for discussion.

In his stimulating paper, Little thinks about New Zealand’s experience in light of eight comparators, four of which he saw as having had a “disappointing economic performance over a long period of time”

- Uruguay

- Switzerland

- Tasmania

- Atlantic provinces of Canada

And four of which “have gone through very difficult periods but moved on to become some of the richest economies in the OECD”

- Denmark

- Finland

- Iceland

- Ireland

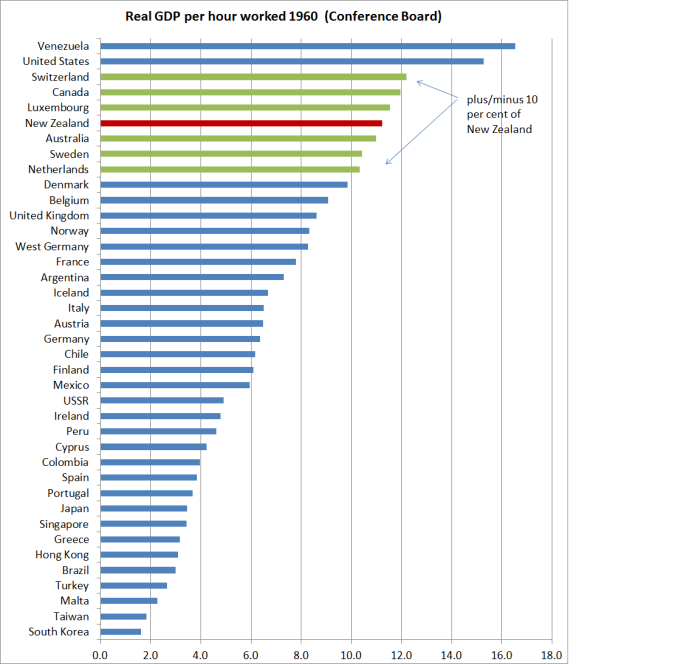

The inclusion of Switzerland might surprise some, since it is – and consistently has been – one of richest countries in the world. But its productivity growth had been strikingly weak over several decades. Overall, it is a fascinating alternative lens to look at New Zealand’s experience through – a contrast to, say, simply looking at the US or the UK, or even the OECD as a whole.

To structure his discussion, Little drew seven “broad lessons”

- Losers can’t be saved. He isn’t quite as pessimistic as this sounds but observes “once you are gifted with the “loser economy” tag, there is no single policy (or even groups of policies) that can easily reverse this decline”.

- Don’t just blame size and distance.

- We spend a lot on education and training but do we get results?

- Technology-Driven Productivity Growth Went Out with the Tech Bubble. NZ firms don’t do much (that is classified as) R&D spending, but “the links between R&D and economic success are not clear”.

- You are either on the internationalization bus or plugging through the mud. NZers attitudes to internationalization weren’t very positive, and the volatility of the real exchange rate had been a problem, holding back our tradables sector/

- Social consensus matters

- Are individual interventions effective?

- Size of government doesn’t matter

- Centralisation isn’t all bad

- FDI can help

- Public infrastructure investment can be a waste of money

His own view, in conclusion, was that three policy areas were paramount for New Zealand, if it was to sustain a higher growth rate in future

- Sound and stable macro policies, with a particular emphasis on a less volatile real exchange rate.

- A shared social vision as to New Zealand’s future

- Greater internationalization (changing attitudes, more emphasis on trade agreements, and “perhaps greater assistance to exporters”.

Any 15 year old paper on a topic of this sort is going to read a bit oddly in places – at the time, for example, Italy was cited as an example of a notably successful economy (unfortunately it has had no per capita growth at all since then). And although all of his four success stories remain much richer than New Zealand, each has had a new very rocky time in the last decade or so.

And whatever any author writes on a topic like this is going to be partly a product of his/her experiences and context. 2001 was two years into the first term of the Labour government, and I suspect Michael Cullen would not have been unreceptive to many of the sorts of messages in this note (which is perhaps why Treasury was able to publish it).

But I wanted to comment on one of the strands of policy Struan emphasizes, and then highlight a few that I was interested to find no mention of (perhaps partly reflecting the fact that today’s context is different to his). And then offer a few thoughts on whether “losers’ can be saved.

The first is the volatility of the real exchange rate. Little notes the materially greater volatility of New Zealand’s real exchange rate than those of Denmark, Iceland, Finland, and Ireland and observes:

“I see this as one of the key reasons why our export performance has been relatively weak compared to more successful economies. While more extreme than New Zealand, the experience of Uruguay and the Southern Cone countries shows than an upward appreciation of the real exchange rate can undermine a reform programme and prevent a country from getting out of a low growth trap……..I would hope that improvements in our monetary framework may resolve the real exchange rate issue.”

What was the context? We had had a relatively volatile real exchange rate in fifteen years since the exchange rate had been floated. In 2001 the real exchange rate was actually very low – only just off its all-time lows – but there had been a lot of recent focus on the conduct of monetary policy. In fact, Struan and I had been the bulk of the secretariat to Lars Svensson’s review of New Zealand’s monetary policy arrangements, which had been commissioned by the incoming Labour government – concerned about the exchange rate, and disconcerted by things like the Bank’s unfortunate Monetary Conditions Index experiment. That inquiry had reported earlier in 2001.

The Reserve Bank has always cautioned against emphasizing the volatility of the real exchange rate as a factor in New Zealand’s economic underperformance. As various people have noted, our real exchange rate is not extraordinarily volatile by advanced country standards – which sample you compare it with matters a lot – and much of the volatility reflects the real and financial external shocks the country faces. I largely agree with the Bank’s perspective on this issue – and it isn’t obvious that much could be done to attenuate the big cycles in the real exchange rate anyway – but we need to be open to the possibility that the impact is greater than we realise (if, eg, fluctuations in commodity prices contribute directly to exchange rate fluctuations, making it very difficult for other industries to successfully emerge and compete internationally). But changing the details of the monetary policy framework isn’t likely to make much difference – we’ve been through a wide variety of regimes over the decades, and had quite big real exchange rate fluctuations in each of them.

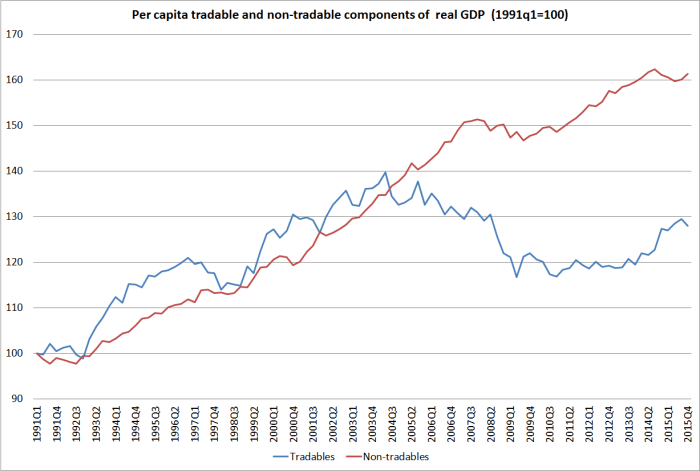

I’ve been more concerned about the average level of the real exchange rate. Right from the early days of the reforms, experts (themselves supportive of the reform programme) have emphasized the importance of a lower real exchange rate as part of a path towards rebalancing the economy and establishing a stronger growth trajectory. It was the Reserve Bank and Treasury view as far back as 1985. Leading international scholars like Anne Krueger and Sebastian Edwards re-emphasized it – partly in reference to the Latin American experience Little alludes to in the quote above. It isn’t a line that is so widely heard in the mainstream these days, but the failure to achieve any per capita growth in New Zealand’s tradables sector in the 15 years since Little was writing suggests that the issue has not gone away. Our persistently high (relative to other advanced countries) real interest rates look to be related to the failure of the exchange rate to adjust – but that gap wouldn’t have been so evident in 2001.

Reading through Little’s paper yesterday, three omissions struck me:

- first, there was no specific mention of Auckland whatever. I’m not critical of that – as I’ve made clear, I think the policy focus on growing Auckland is seriously misguided – but one could not imagine a similar paper today not touching on the Auckland (and agglomeration) issues.

- second, there was no mention of taxation and particular not the taxation of capital. Perhaps it isn’t a material explanatory factor, or a tool that might make much difference, but the Irish experience with a very low company tax rate, and the Nordic experience with setting tax rates on capital income much lower than those of labour income look as though they should be candidates for inclusion in a list of explanatory factors.

- third, there was no mention of immigration (policy) at all. Emigration – from all the “losers” – got a mention, but not the role of policy-facilitated immigration of non-citizens. Perhaps it just reflected the times – overall net immigration was quite modest around the turn of the century – but the scale of our non-citizen immigration programme, unparalleled in the other countries and explicitly seen as an economic growth lever, looks as though it probably should have rated a mention of some sort. (Of course, the paper was written just before the New Zealand house price boom started, so not even immediate house price effects of immigration were salient then).

Perhaps relatedly, in his final section Little talks of the contrast between fixed and mobile factors of production, emphasizing labour (“at least to an extent”) and social institutions as fixed factors. It was a surprise that, in an economy whose exports are overwhelmingly natural resource based, our land wasn’t considered as an important fixed factor – an opportunity and, perhaps, a constraint.

I’m explicitly not writing to criticize Little’s paper. There is so little good material on these issues, and his note offers a lens that helps stimulate one’s thoughst even when not fully agreeing with it. But there is perhaps one area where experience might suggest he was a little too pessimistic. Even his “losers” can, it seems, turn themselves around, at least to some extent.

Of course, even in 2000 we knew that in some cases – the better countries of Eastern Europe were already rebounding from the dark decades of Communist rule. But it seems to have been true of some of Little’s losers too.

Switzerland’s productivity growth still isn’t stellar, but the Swiss have very large net foreign assets. I checked the net national income per capita data from the OECD this morning, and over the last 15 years, Switzerland – already richer than most – has outstripped growth in the OECD as a whole, and in the United States in particular.

For Uruguay, I showed this chart a few weeks ago, of TFP growth over the last couple of decades.

Uruguay has a long way to go, but they’ve made an impressive start.

And what about Tasmania? The Australian state GDP data start from 1990, and Little writing in late 2001 discusses the record in the 1990s. Here is how NSW and Victoria, on the one hand, and Tasmania on the other have done over the subperiods 1990 to 2001 and 2001 to 2015.

Quite a rebound in relative performance.

Quite a rebound in relative performance.

New Zealand, meanwhile, has shown no signs of even beginning to close any of the big gaps in productivity – if anything, on many measures they are still widening.

In terms of my narrative of New Zealand’s policy problems, one thing that marks out territories, states or regions from countries is that the former do not have an immigration policy. Population growth in Tasmania may be very slightly influenced by Australia’s overall immigration programme, but largely people move to Tasmania only if the relative opportunities within Australia are better in Tasmania than they are elsewhere in Australia. Tasmania looks like the sort of place – like my story of New Zealand – that can generate good incomes for a small number of people. And in the last 25 years, Tasmania’s population has increased by around 12 per cent, while the populations of New South Wales and Victoria have increased by more than 30 per cent. By contrast, in New Zealand’s case, the central government’s immigration policy directly boosts the population of the entire country. Unlike Tasmania, we’ve had more than 35 per cent population growth since 1990, mostly concentrated in Auckland. In such an unpropitious location for economic activity, it has just made it that much harder to even begin to close the income gaps.

Old papers aren’t to everyone’s taste, but the issues Little’s paper treats (or those treated in my own speculative entry to the field from a few years ago) haven’t gone away. Unfortunately there is little sign of our political leaders – government or opposition – really doing much to reverse the decline of this “loser”.

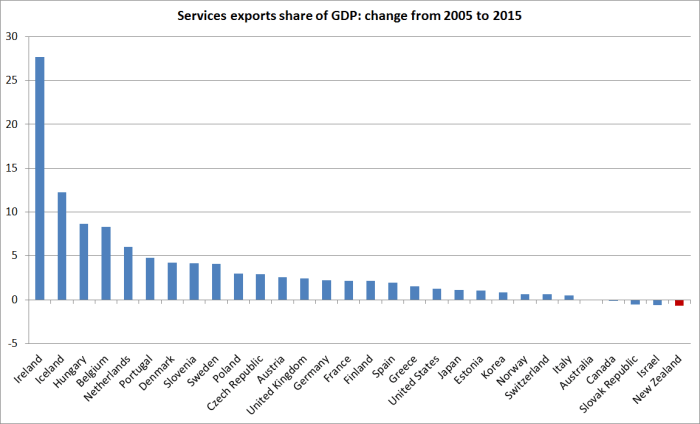

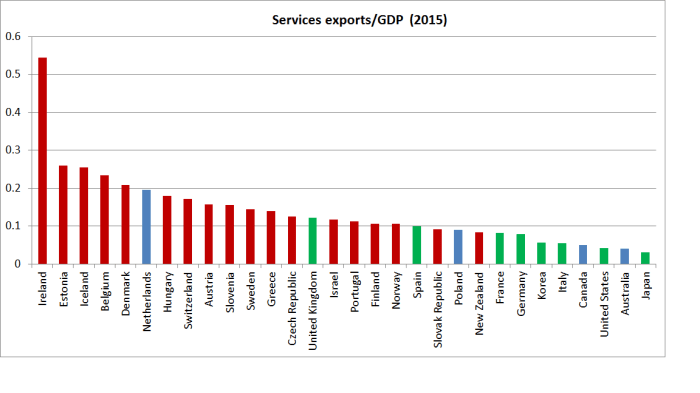

Large countries don’t tend to do as much international trade as small countries – they don’t need to, there are plenty of opportunities and markets at home. I’ve highlighted the large countries (more than 40m people) in green, and the small countries (under 11m, where there is a natural break) in red. New Zealand has the lowest services export share of any of the small countries (and, by the look of it, the lowest real dollar value of services exports as well) . Of course, we are much more remote than the other small countries, but it just highlights the difficulty of generating really high incomes for lots of people in a place so distant.

Large countries don’t tend to do as much international trade as small countries – they don’t need to, there are plenty of opportunities and markets at home. I’ve highlighted the large countries (more than 40m people) in green, and the small countries (under 11m, where there is a natural break) in red. New Zealand has the lowest services export share of any of the small countries (and, by the look of it, the lowest real dollar value of services exports as well) . Of course, we are much more remote than the other small countries, but it just highlights the difficulty of generating really high incomes for lots of people in a place so distant.