Tempting as it is to write about the failures and weaknesses of the New Zealand public sector – and there is plenty more grist to the mill, reinforcing Kerry McDonad’s forcefully expressed concerns, even in this morning’s newspaper – or the inadequate performance of the Reserve Bank in conducting monetary policy, as the TWI now sits above 76, I’m going to write today about some longer-term issues.

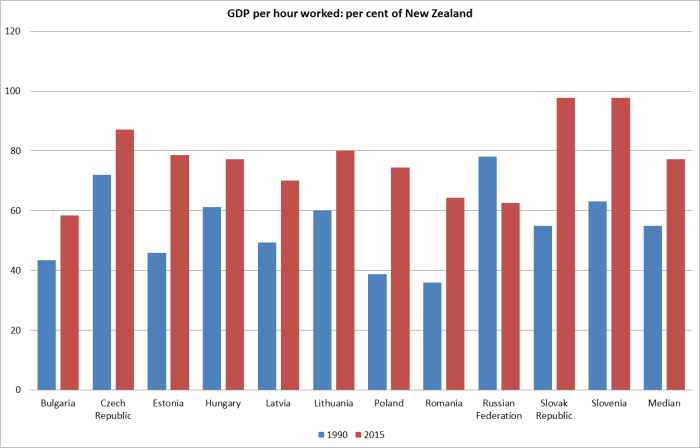

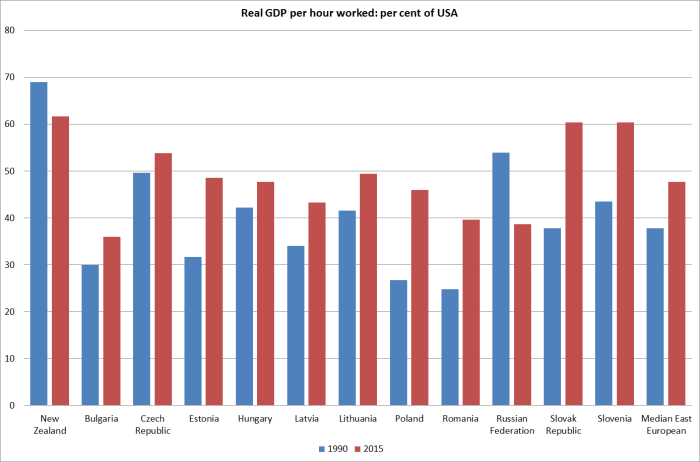

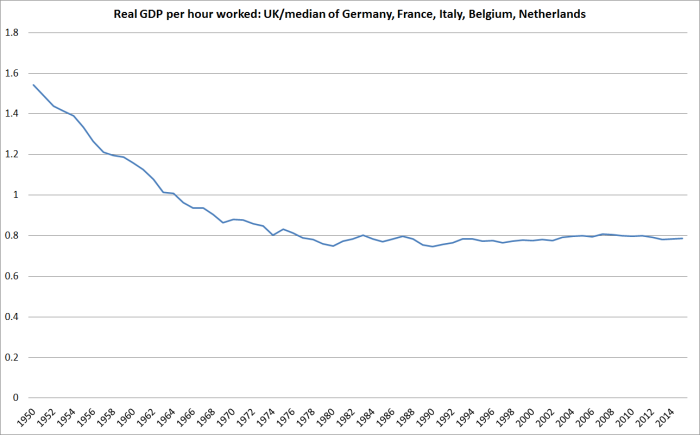

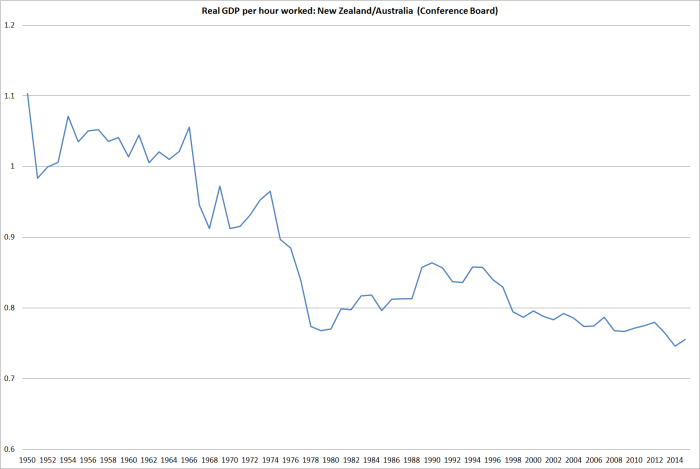

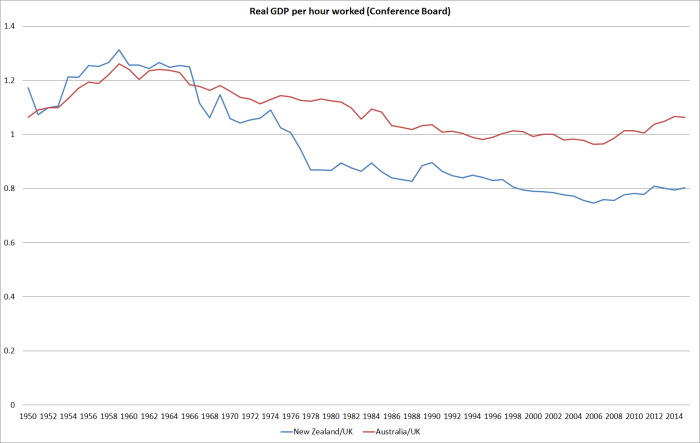

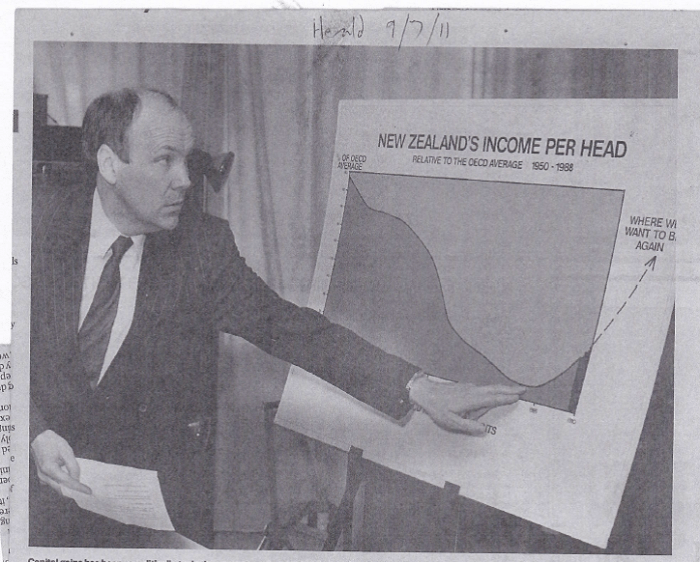

Of all the issues I write about on this blog, probably the one that concerns me most is New Zealand’s long-term structural economic decline, relative to other advanced countries. That decline has been underway for many decades, and if the rate of decline has slowed there is certainly no sign of the gaps beginning to close. Once upon a time that decline seemed to bother people, but sadly we seem to have got used to it. And perhaps too people are more cynical – they’ve heard various stories over the years as to what might reverse the decline, and even when tried none seem to have worked (enough).

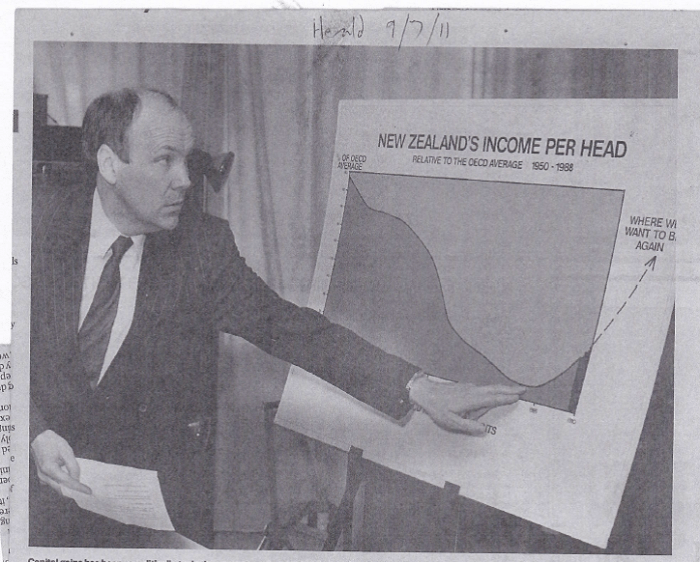

This photo, after all, was taken in 1989 – a generation ago now.

I don’t think the current state of the affairs is good enough. There is no political leadership that treats the issue as a priority, debate is virtually non-existent on any sustained basis, and the economic conditions that have seen almost a million New Zealanders (net) leave permanently in recent decades haven’t changed. I don’t want my kids to grow up to discover that most of the best opportunities for them and their kids are abroad.

Readers here recognize the serious relative decline we’ve experienced over many decades. But I often get comments, whether sympathetic or critical, asking what I would do to change things – often with the text, or sub-text, “and why are you always banging on about immigration policy at the expense of everything else?”.

There are plenty of things about our economic policy (broadly defined) that I would change. Many of them are in areas where I have not spent a lot of time or effort looking at the issues and options in great detail, and so in a spare-time blog I don’t write about them. And quite a few seem to me like things that would be worth changing, but might not make that much difference at all to measures like GDP per capita, or per hour worked. I prefer to focus my efforts in areas which might make a material difference – individually, or even as a package – and, perhaps, to critiquing proposals that others suggest might make a big difference, but where I disagree. I happen to favour fully-funded school choice, while I suspect most readers don’t. In terms of economic performance, no one would argue it matters that much, so why alienate people who might be sympathetic to my core arguments and analysis? Then again, some of my friends on the (economic, pro-market) right are deeply uneasy about my immigration analysis, so from time to time I do like to remind them that my underlying model is a strongly market-oriented one. In the end, there are only so many hours in a day, and only so much of my time I want to devote to these issues.

When the National Party led government assumed office in 2008, they set up the 2025 Taskforce. As it is described on the Treasury website

As part of the Confidence and Supply Agreement between the National and ACT parties reached immediately after the 2008 election, the Government committed to closing the income gap with Australia by 2025 and to establishing an advisory group both to report annually on progress towards achieving that goal and to make recommendations about how best to achieve it.

I don’t suppose the National Party would have been averse to the gap closing. But the Taskforce was pretty much forced on them by ACT – minor parties entering Confidence and Supply Agreements get to pick a few policies that the dominant governing party agrees to implement, and this was ACT’s that year.

It was an under-resourced exercise from the start. The one Australian member appointed to the Taskforce by our government was staggered at how little time and resource they were given. Treasury provided the Secretariat to the Taskforce, and I got closely involved in that process – I was at Treasury at the time, and having worked closely with Don Brash previously, he – as chair of the Taskforce – was keen to have me involved. The first report of the Taskforce, issued in late 2009, is the one fairly comprehensive attempt in term of the current government to provide a list of recommendations that, if adopted, offered a reasonable chance of being able to catch up with Australia. Based on historical experiences with convergence, catching up over 16 years looked to the Taskforce to be demanding, but not impossible. If most of the words in the Report flowed directly from my pen, the recommendations are those of the Taskforce members. But at the time, I agreed with most of them – even if, even then, not all seemed overly important.

Yesterday I went back and read through the 50 or so specific recommendations in the report (they are on pages 8 to 11 are the link above). I could go through them one by one, but that would bore most readers, and bore me, and in many cases wouldn’t add much value. But, like the Taskforce, I support:

- lowering the share of GDP accounted for by government spending,

- stronger institutional disciplines around new spending proposals,

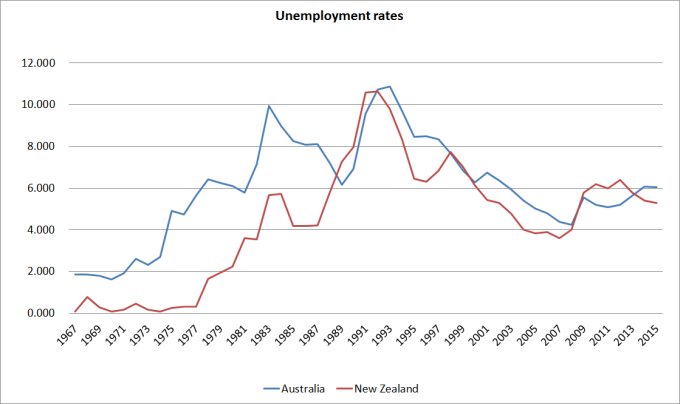

- steps to cut the high number of working age people on welfare benefits,

- increasing the age of NZS eligibility and indexing the age to future changes in life expectancy,

- introduction of a funder-provider model for the hospital sector and the school sector, allowing new provider entrants whether government or private owned.

- removal of the substantially increased childcare subsidies introduced a decade or so ago,

- government-imposed fee caps on university fees should be abolished,

- reductions in tax rates should have regard to “the evidence that taxes on capital income can be particularly detrimental to economic performance”,

- all government shares in businesses where competition is actual or feasible should be sold,

- the NZSF should be wound-up and proceeds used to repay government debt,

- congestion charging should be introduced in central Auckland (in particular) and full economic road-user charging should be introduced as feasible,

- mining developments “on or under sensitive Crown land should generally be permitted provided that they pass a full cost-benefit test”,

- a Regulatory Responsibility Bill should be enacted,

- an independent Productivity Commission should be established,

- resource management law should be reviewed from first principles,

- in zoning land for residential purposes, local authorities should have to report regularly on, and take explicit account of, differences in land prices between residential-zoned undeveloped land and other undeveloped land in similar areas,

- provisions allowing for probationary periods in employment should be extended

- increases in youth and adult minimum wages – relative to median incomes – over the previous decade should be reversed,

- all remaining tariffs should be removed unilaterally,

- foreign investment restrictions should be liberalized,

- Zespri’s kiwifruit export monopoly should be removed.

A few of these have actually happened, or might soon happen.

I’d support all of those proposals. But as I came away from my involvement with the Taskforce, I gradually came to the view that they just didn’t seem like enough to make large in-roads on the productivity and income gaps that had opened up over previous decades. People operating within different “models” of the economy might disagree, but as I tried to think hard about the distinctive features of New Zealand’s underperformance I couldn’t convince myself that this was a game-changing agenda. After all, radical as it was in some respects, it was less far-reaching in the important respects than the reform agenda implemented over 1984 to 1993, which hadn’t reversed our decline. Arguments that “oh, we just hadn’t gone quite far enough” don’t typically ring very persuasively – whoever is running them is simply inviting policymakers to double up on a bet which, so far, has shown no signs of paying off.

There is probably a variety of “models” people have in mind for thinking about New Zealand’s economic underperformance. I’ll stylize (caricature) two of them as “small government” and “smart government”. One of the finest representatives of the small government school in New Zealand was the late Roger Kerr, who had thought hard about economic performance and New Zealand for a long time, and was always will to engage on the issues. I think he probably thought – and his public and private comments at the time suggest – that the 2025 Taskforce report didn’t go quite far enough, and didn’t grapple with all the issues it could have, but that if only we got government spending down to perhaps 15 to 20 per cent of GDP, facilitated foreign investment, reformed the provision of health and education, privatized government and local authority operating businesses, liberalised the labour market, and sorted out the RMA and the creeping advance of other regulation, we’d be well on the way to catching Australia and other richer OECD countries.

I’m not sure there is single person representative of what I would call the “smart government” school, but it is the sort of thinking that these days seem to pervade places like the OECD, and key domestic government agencies – be it Treasury, MBIE, or even the Productivity Commission. It is the hunt for a smarter set of interventions – ones around R&D are popular, but it might include top-down visions as to what cities should look like, granting eminent domain powers to Urban Development Authorities, getting a better class of immigrants going to different regions, getting better data on how best to intervene in individuals’ lives etc. If this seems like a caricature that is partly because (a) there is no properly developed case made for a set of reforms along these lines that might transform New Zealand’s prospects, and (b) because in this post I haven’t the space to develop the alternative fully myself. But the gist seems to be that our problem isn’t government interventions, but just that we had the wrong bureaucrats and ministers making the wrong interventions, and if only we adopted this alternative set we’d be fine. And, of course, there is no doubt plenty of regulation/law required in a modern market economy, and we should always be trying to improve it.

My stance is much closer to the Kerr end of the spectrum. In particular, I think it is a safe observation that governments, and government interventions, are more often the source of a country’s economic problems than the answer to them. Of course, governments don’t exist in a vacuum, and so government policies are often a reflection of the societies they govern, and the problems and dysfunctions in those societies. But the problems often manifest in misplaced economic interventions. On the other hand, “culture” matters too: keeping taxes low, regulation light, markets open, and property rights secure wouldn’t transform Zambia, say, into an OECD success story, at least not in a single lifetime.

But in thinking about New Zealand, we have some advantages. These include:

- we were already rich (high GDP per capita or per hour worked) for a long time,

- we shared a culture (broadly speaking) with most of the richest and most successful countries in the world (Anglo and Northern European)

- as part of that, we share key institutions such as the rule of law and reasonable protections of private property rights.

That should help us narrow down our search for answers. We can try to think, in a reasonably structured way, about similarities and differences between New Zealand and these other (typically much richer, higher levels of productivity) countries.

On the similarities side, it is worth bearing mind that the overall size of government isn’t that different than in these other countries (be it spending share, ownership of assets, or regulation), and actually on one of those dimensions – government spending as a share of GDP – there is quite a wide range of experiences among successful countries, and we are towards the middle of the pack. But if government spending as share of GDP was perhaps 55 per cent, there might be a good case for seeing pulling back the size of government spending (and hence overall tax rates) as key element in any package of reforms (a putative list of Top 5 Reforms).

House price problems are pretty similar too. Scandalous here and in most of those countries too, but not a prima facie reason to think distorted housing supply markets might be at the heart of our productivity and economic performance failures.

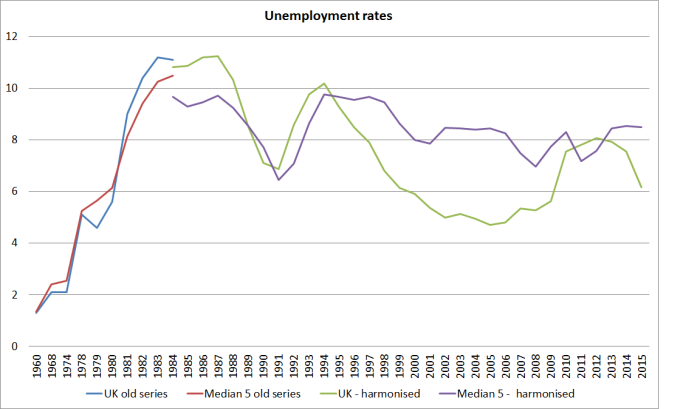

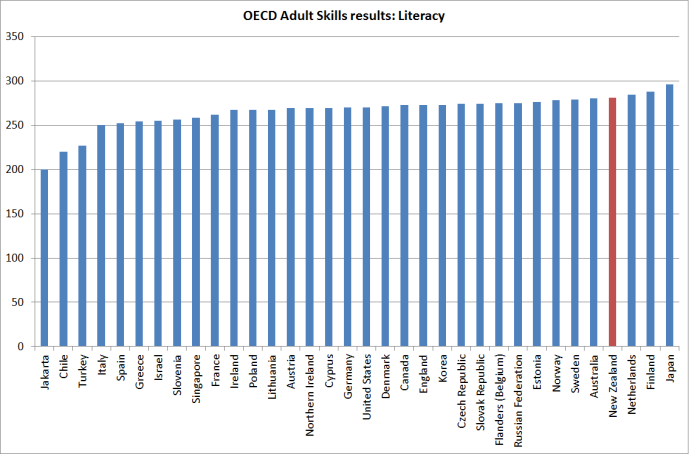

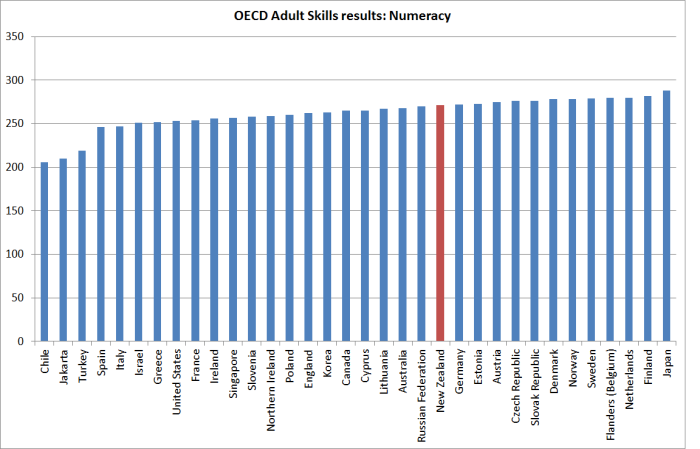

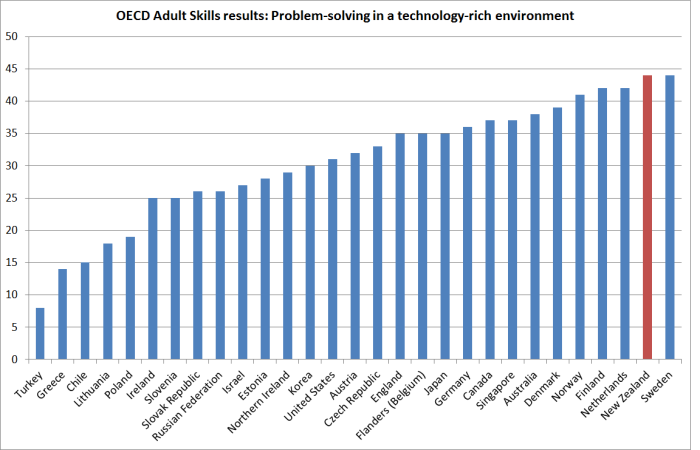

For all the opportunities there might be to improve our schools and universities, “skills” doesn’t really look like a credible huge difference. We used to have quite a low rate of participation in tertiary education, but even that has change in recent decades. I’d also tend to emphasise the similarities, more than the differences, between our welfare system and those in the successful advanced economies – in some areas, ours might be less of a “tax” on growth and economic performance (eg NZS deters labour market participation less, and in some more so, but overall the differences don’t look decisive.

What are some potentially significant differences:

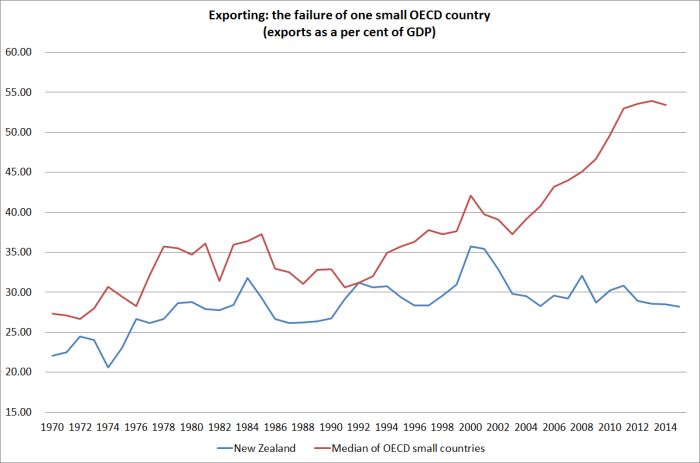

- we are small (but not extremely so, cf Ireland, Denmark, Finland, Iceland),

- we are remote (though on typical measures) similar to Australia),

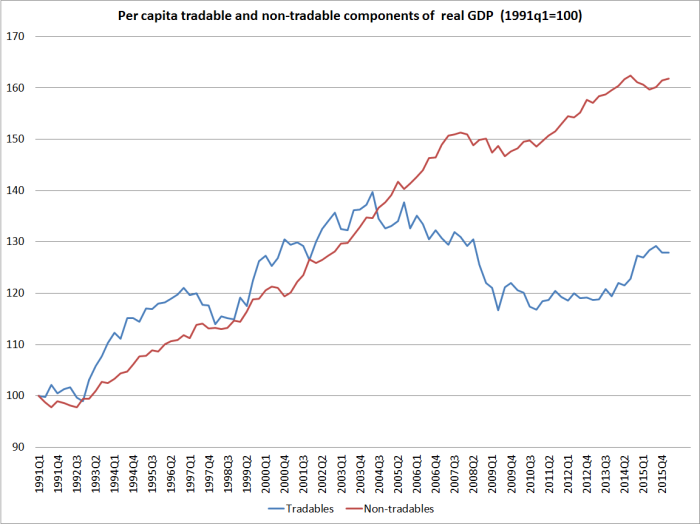

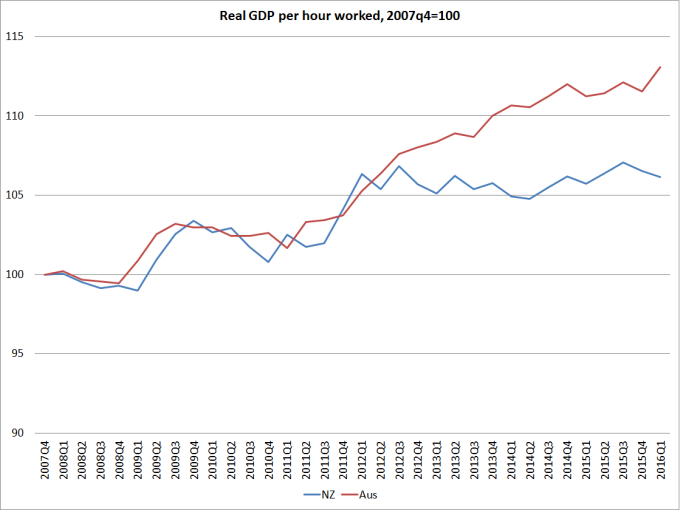

- we’ve had persistently low rates of business investment (including in R&D) going back decades, even more obviously once one allows for population growth differentials (countries with faster-growing populations,

- we remain heavily natural resource dependent (like Australia and, to a lesser extent, Canada),

- we have had, for decades, the highest real interest rates in the OECD,

- despite our substantial and sustained deterioration in economic performance, our real exchange rate has not adjusted downwards,

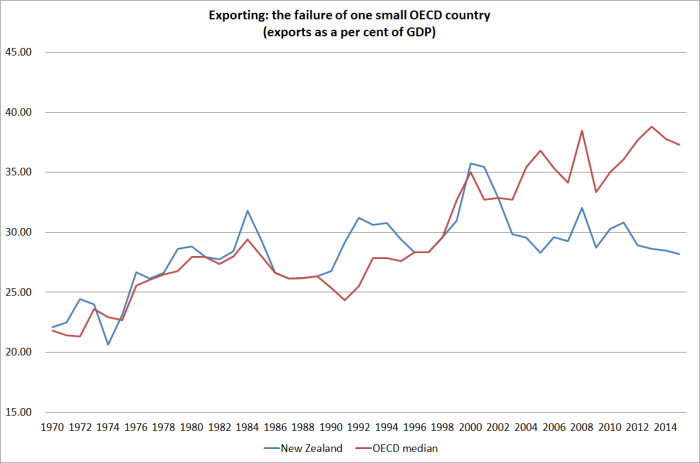

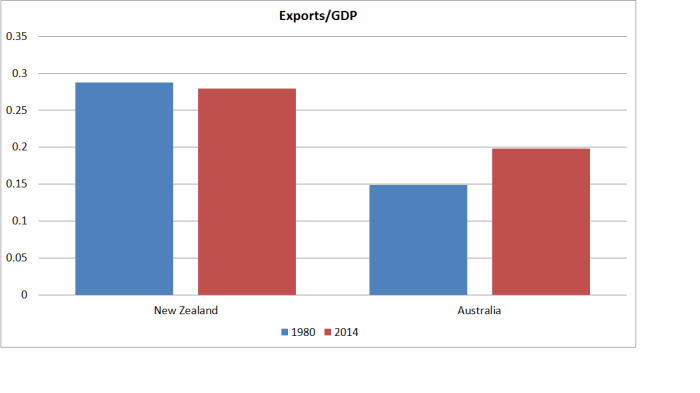

- we have had very little growth in exports as a share of GDP, such that our export share is now very low for such a small country (small countries typically do more foreign trade than large ones)

- we’ve had a lower national savings rate than many of these countries,

- we have typically had the largest negative NIIP position (per cent of GDP) of any of these countries,

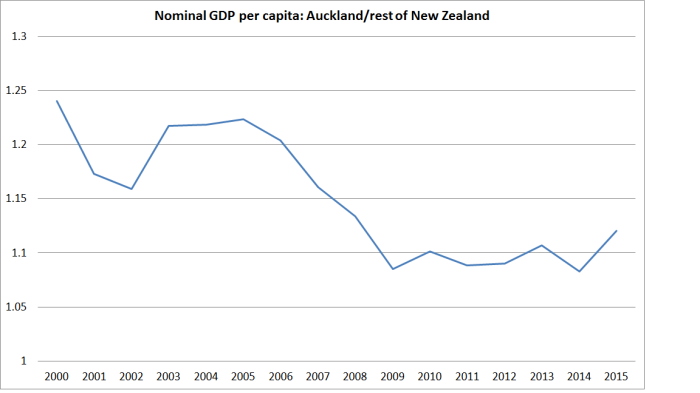

- our single moderately large city has been an economic laggard (GDP per capita) in recent decades, unlike the typical advanced country experience,

- we’ve had a very large, decades-long, net outflow of our own citizens (unlike most successful countries, although similar to what Ireland had for decades)

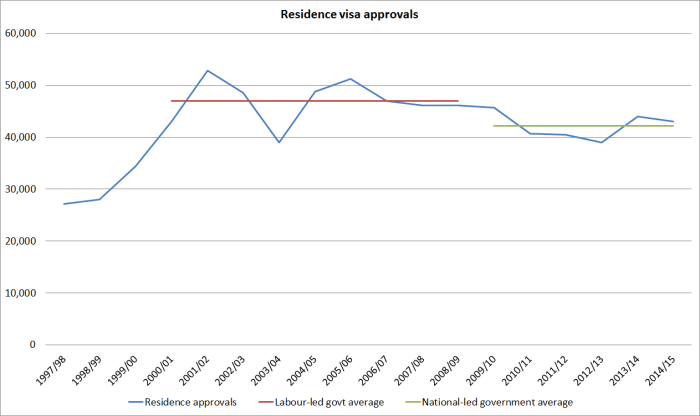

- we have an unusually large target level of non-citizen immigration

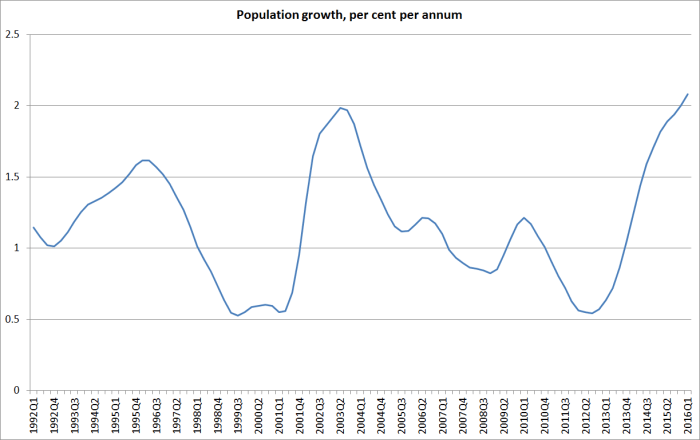

- over the decades since our economic deterioration became evident, we have had faster population growth than many, but not all, these countries.

I suspect that most of those who think about the challenges of New Zealand’s economic underperformance would grant most of those stylized facts. I’ve tried to write them in a way that doesn’t overstate any of them individually. Perhaps some will think I’ve left out some key stylized facts, and if so I’d happily consider them. Stories and explanations, and policy prescriptions, need to be fitted to the stylized facts. But equally, everyone starts with a “model”, and some implicit assumptions about what facts matter. But we can all have blind spots.

My story has developed to try to take account of the sorts of similarities and differences I’ve listed above. I start by looking around the policy interventions that might be messing things up (recall that my underlying model is that firms invest and generate prosperity in countries with sound basic institutions unless government interventions materially distort those prospects).

Plenty of people worry about New Zealand’s savings rate, but when one looks across time and across countries it isn’t obvious that our government policy settings around savings (ie differences from those abroad) can explain different savings outcomes. That was the somewhat-reluctant conclusion of a Treasury exercise I had some involvement with a few years ago. Perhaps an alternative explanation might see relatively modest savings rates as an endogenous response to whatever makes the business investment environment here sufficiently unattractive to generate those low rates of investment. After all, business depreciation and retained earnings (to take advantage of great business opportunities) are a large, and often neglected, component of national savings. And it isn’t as if government is running large deficits either.

And low business investment must also be related – common causal factors – to the very low rate of growth of exports (most of the potential market for many firms is the wider world), which in turn must be related to the persistently high exchange rate. Some people try to argue that our interest rates have been high because we have so much debt, and markets “punish” us for it, but actually our debt (NIIP) has been large for 25 years – plenty of time for people to adjust their behavior and see any “risk premium” dissipate. Perhaps as importantly, high risk premia are simply inconsistent with persistently high exchange rates – when markets are really jittery, asset prices are typically weak, not persistently surprisingly strong.

Low business investment (as a share of GDP) might also be related to a relative lack of profitable opportunities here – even if the exchange rate was lower. There is a lot of resistance to this idea, but the resistance typically does not take seriously economic geography. People repeatedly focus on the places where there are lots of people (in the advanced world) and hardly at all on the places where there are not lots of people – presumably because profitable opportunities are just not there (in Nebraska, as opposed say to San Francisco). People leave – or don’t go to – those places when they have better alternatives. New Zealanders, for example, move to Australia.

So I’m driven towards a story that emphasizes the combination of the limited high-returning economic opportunities that our location/distance seems to have offered, the role of excess aggregate demand (which has given us persistently high interest rates, despite the apparently poor opportunities, and a high real exchange rate), and at the same time a population that is still growing rapidly (trend basis, not just the last year) largely now as a result of immigration policy. And – to revert to the point about looking for government interventions that, however well-intentioned, are messing things up – we have an unusually large non-citizen immigration programme, especially for such an unusually underperforming country. Among the government’s economic policy interventions, it is large and distinctive.

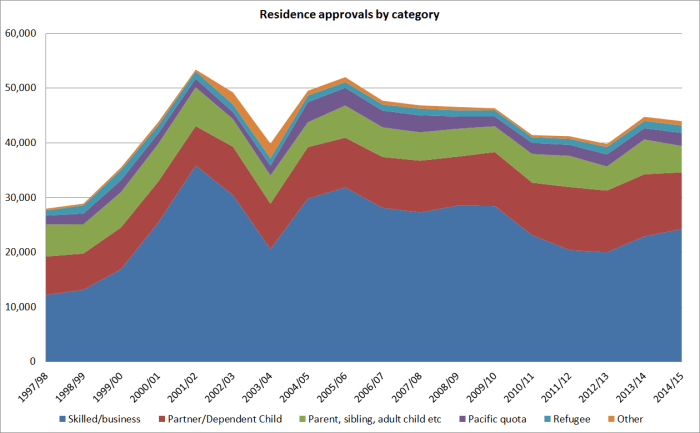

For quite a few years, I believed the rhetoric that it was all “good quality” migration, but as I looked into it I found – as others have, including The Treasury – that actually, it really isn’t such good quality migration after all (better than some countries’ experiences, but just not really that skills-focused). Perhaps really able, highly-skilled, people don’t want to come in large numbers to a small, remote, underperforming country, that doesn’t seem to be able to support lots of highly profitable outward-oriented industries dependent on things other than the (essentially) fixed quantity of natural resources?

I could write lots more, but this post has already got rather long. My point was not, in a single post, to make a comprehensive case for every strand of my argument. Thinking about it this morning, I realized that I laid some of the foundations – especially around the interest rate/exchange rate/investment nexus – in a series of posts a year ago. But readership has increased very substantially since then (and my impression was that most readers back then knew me, and had some past exposure to my arguments, which is no longer the case). I may dig out some of that material and re-run some updated posts in coming weeks.

And having got to the end I still don’t want to leave the impression that other potential reforms don’t have a place. A standard line – the 2025 Taskforce used it – is that distance/location aren’t things we can do much about, so we just need to make sure we run really good policies to offset the disadvantages. I have quite a lot of sympathy with that view – and good policy is always better than poor policy – but as a general proposition it can be a distraction from identifying any key areas in which ill-judged policy interventions (even ones that might make sense for other countries in other circumstances) might actually be working us against making the most, in per capita GDP terms for New Zealanders, of what we have and where we are. I think our highly unusual – in context – immigration policy is a prime example of that.

New Zealand’s export share of GDP hasn’t changed in 35 years.

New Zealand’s export share of GDP hasn’t changed in 35 years.

Note: The x axis is scaled so that each marker is ten times the magnitude of the previous one.

Note: The x axis is scaled so that each marker is ten times the magnitude of the previous one.